- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Patient Perspectives

- Methods Corner

- Science for Patients

- Invited Commentaries

- ESC Content Collections

- Author Guidelines

- Instructions for reviewers

- Submission Site

- Why publish with EJCN?

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Read & Publish

- About European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing

- About ACNAP

- About European Society of Cardiology

- ESC Publications

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- War in Ukraine

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, why patient journey mapping, how is patient journey mapping conducted, use of technology in patient journey mapping, future implications for patient journey mapping, conclusions, patient journey mapping: emerging methods for understanding and improving patient experiences of health systems and services.

Lemma N Bulto and Ellen Davies Shared first authorship.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Lemma N Bulto, Ellen Davies, Janet Kelly, Jeroen M Hendriks, Patient journey mapping: emerging methods for understanding and improving patient experiences of health systems and services, European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing , 2024;, zvae012, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvae012

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Patient journey mapping is an emerging field of research that uses various methods to map and report evidence relating to patient experiences and interactions with healthcare providers, services, and systems. This research often involves the development of visual, narrative, and descriptive maps or tables, which describe patient journeys and transitions into, through, and out of health services. This methods corner paper presents an overview of how patient journey mapping has been conducted within the health sector, providing cardiovascular examples. It introduces six key steps for conducting patient journey mapping and describes the opportunities and benefits of using patient journey mapping and future implications of using this approach.

Acquire an understanding of patient journey mapping and the methods and steps employed.

Examine practical and clinical examples in which patient journey mapping has been adopted in cardiac care to explore the perspectives and experiences of patients, family members, and healthcare professionals.

Quality and safety guidelines in healthcare services are increasingly encouraging and mandating engagement of patients, clients, and consumers in partnerships. 1 The aim of many of these partnerships is to consider how health services can be improved, in relation to accessibility, service delivery, discharge, and referral. 2 , 3 Patient journey mapping is a research approach increasingly being adopted to explore these experiences in healthcare. 3

a patient-oriented project that has been undertaken to better understand barriers, facilitators, experiences, interactions with services and/or outcomes for individuals and/or their carers, and family members as they enter, navigate, experience and exit one or more services in a health system by documenting elements of the journey to produce a visual or descriptive map. 3

It is an emerging field with a clear patient-centred focus, as opposed to studies that track patient flow, demand, and movement. As a general principle, patient journey mapping projects will provide evidence of patient perspectives and highlight experiences through the patient and consumer lens.

Patient journey mapping can provide significant insights that enable responsive and context-specific strategies for improving patient healthcare experiences and outcomes to be designed and implemented. 3–6 These improvements can occur at the individual patient, model of care, and/or health system level. As with other emerging methodologies, questions have been raised regarding exactly how patient journey mapping projects can best be designed, conducted, and reported. 3

In this methods paper, we provide an overview of patient journey mapping as an emergent field of research, including reasons that mapping patient journeys might be considered, methods that can be adopted, the principles that can guide patient journey mapping data collection and analysis, and considerations for reporting findings and recognizing the implications of findings. We summarize and draw on five cardiovascular patient journey mapping projects, as examples.

One of the most appealing elements of the patient journey mapping field of research is its focus on illuminating the lived experiences of patients and/or their family members, and the health professionals caring for them, methodically and purposefully. Patient journey mapping has an ability to provide detailed information about patient experiences, gaps in health services, and barriers and facilitators for access to health services. This information can be used independently, or alongside information from larger data sets, to adapt and improve models of care relevant to the population that is being investigated. 3

To date, the most frequent reason for adopting this approach is to inform health service redesign and improvement. 3 , 7 , 8 Other reasons have included: (i) to develop a deeper understanding of a person’s entire journey through health systems; 3 (ii) to identify delays in diagnosis or treatment (often described as bottlenecks); 9 (iii) to identify gaps in care and unmet needs; (iv) to evaluate continuity of care across health services and regions; 10 (v) to understand and evaluate the comprehensiveness of care; 11 (vi) to understand how people are navigating health systems and services; and (vii) to compare patient experiences with practice guidelines and standards of care.

Patient journey mapping approaches frequently use six broad steps that help facilitate the preparation and execution of research projects. These are outlined in the Central illustration . We acknowledge that not all patient journey mapping approaches will follow the order outlined in the Central illustration , but all steps need to be considered at some point throughout each project to ensure that research is undertaken rigorously, appropriately, and in alignment with best practice research principles.

Steps for conducing patient journey mapping.

Five cardiovascular patient journey mapping research examples have been included in Figure 1 , 12–16 to provide specific context and illustrate these six steps. For each of these examples, the problem or gap in practice or research, consultation processes, research question or aim, type of mapping, methods, and reporting of findings have been extracted. Each of these steps is then discussed, using these cardiovascular examples.

Examples of patient journey mapping projects.

Define the problem or gap in practice or research

Developing an understanding of a problem or gap in practice is essential for facilitating the design and development of quality research projects. In the examples outlined in Figure 1 , it is evident that clinical variation or system gaps have been explored using patient journey mapping. In the first two examples, populations known to have health vulnerabilities were explored—in Example 1, this related to comorbid substance use and physical illness, 13 and in Example 2, this related to geographical location. 13 Broader systems and societal gaps were explored in Examples 4 and 5, respectively, 15 , 16 and in Example 3, a new technologically driven solution for an existing model of care was tested for its ability to improve patient outcomes relating to hypertension. 14

Consultation, engagement, and partnership

Ideally, consultation with heathcare providers and/or patients would occur when the problem or gap in practice or research is being defined. This is a key principle of co-designed research. 17 Numerous existing frameworks for supporting patient involvement in research have been designed and were recently documented and explored in a systematic review by Greenhalgh et al . 18 While none of the five example studies included this step in the initial phase of the project, it is increasingly being undertaken in patient partnership projects internationally (e.g. in renal care). 17 If not in the project conceptualization phase, consultation may occur during the data collection or analysis phase, as demonstrated in Example 3, where a care pathway was co-created with participants. 14 We refer readers to Greenhalgh’s systematic review as a starting point for considering suitable frameworks for engaging participants in consultation, partnership, and co-design of patient journey mapping projects. 18

Design the research question/project aim

Conducting patient journey mapping research requires a thoughtful and systematic approach to adequately capture the complexity of the healthcare experience. First, the research objectives and questions should be clearly defined. Aspects of the patient journey that will be explored need to be identified. Then, a robust approach must be developed, taking into account whether qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods are more appropriate for the objectives of the study.

For example, in the cardiac examples in Figure 1 , the broad aims included mapping existing pathways through health services where there were known problems 12 , 13 , 15 , 16 and documenting the co-creation of a new care pathway using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods. 14

In traditional studies, questions that might be addressed in the area of patient movement in health systems include data collected through the health systems databases, such as ‘What is the length of stay for x population’, or ‘What is the door to balloon time in this hospital?’ In contrast, patient mapping journey studies will approach asking questions about experiences that require data from patients and their family members, e.g. ‘What is the impact on you of your length of stay?’, ‘What was your experience in being assessed and undergoing treatment for your chest pain?’, ‘What was your experience supporting this patient during their cardiac admission and discharge?’

Select appropriate type of mapping

The methods chosen for mapping need to align with the identified purpose for mapping and the aim or question that was designed in Step 3. A range of research methods have been used in patient journey mapping projects involving various qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods techniques and tools. 4 Some approaches use traditional forms of data collection, such as short-form and long-form patient interviews, focus groups, and direct patient observations. 18 , 19 Other approaches use patient journey mapping tools, designed and used with specific cultural groups, such as First Nations peoples using artwork, paintings, sand trays, and photovoice. 17 , 20 In the cardiovascular examples presented in Figure 1 , both qualitative and quantitative methods have been used, with interviews, patient record reviews, and observational techniques adopted to map patient journeys.

In a recent scoping review investigating patient journey mapping across all health care settings and specialities, six types of patient journey mapping were identified. 3 These included (i) mapping key experiences throughout a period of illness; (ii) mapping by location of health service; (iii) mapping by events that occurred throughout a period of illness; (iv) mapping roles, input, and experiences of key stakeholders throughout patient journeys; (v) mapping a journey from multiple perspectives; and (vi) mapping a timeline of events. 3 Combinations or variations of these may be used in cardiovascular settings in the future, depending on the research question, and the reasons mapping is being undertaken.

Recruit, collect data, and analyse data

The majority of health-focused patient journey mapping projects published to date have recruited <50 participants. 3 Projects with fewer participants tend to be qualitative in nature. In the cardiovascular examples provided in Figure 1 , participant numbers range from 7 14 to 260. 15 The 3 studies with <20 participants were qualitative, 12 , 14 , 16 and the 2 with 95 and 260 participants, respectively, were quantitative. 13 , 15 As seen in these and wider patient journey mapping examples, 3 participants may include patients, relatives, carers, healthcare professionals, or other stakeholders, as required, to meet the study objectives. These different participant perspectives may be analysed within each participant group and/or across the wider cohort to provide insights into experiences, and the contextual factors that shape these experiences.

The approach chosen for data collection and analysis will vary and depends on the research question. What differentiates data analysis in patient journey mapping studies from other qualitative or quantitative studies is the focus on describing, defining, or exploring the journey from a patient’s, rather than a health service, perspective. Dimensions that may, therefore, be highlighted in the analysis include timing of service access, duration of delays to service access, physical location of services relative to a patient’s home, comparison of care received vs. benchmarked care, placing focus on the patient perspective.

The mapping of individual patient journeys may take place during data collection with the use of mapping templates (tables, diagrams, and figures) and/or later in the analysis phase with the use of inductive or deductive analysis, mapping tables, or frameworks. These have been characterized and visually represented in a recent scoping review. 3 Representations of patient journeys can also be constructed through a secondary analysis of previously collected data. In these instances, qualitative data (i.e. interviews and focus group transcripts) have been re-analysed to understand whether a patient journey narrative can be extracted and reported. Undertaking these projects triggers a new research cycle involving the six steps outlined in the Central illustration . The difference in these instances is that the data are already collected for Step 5.

Report findings, disseminate findings, and take action on findings

A standardized, formal reporting guideline for patient journey mapping research does not currently exist. As argued in Davies et al ., 3 a dedicated reporting guide for patient journey mapping would be ill-advised, given the diversity of approaches and methods that have been adopted in this field. Our recommendation is for projects to be reported in accordance with formal guidelines that best align with the research methods that have been adopted. For example, COREQ may be used for patient journey mapping where qualitative methods have been used. 20 STROBE may be used for patient journey mapping where quantitative methods have been used. 21 Whichever methods have been adopted, reporting of projects should be transparent, rigorous, and contain enough detail to the extent that the principles of transparency, trustworthiness, and reproducibility are upheld. 3

Dissemination of research findings needs to include the research, healthcare, and broader communities. Dissemination methods may include academic publications, conference presentations, and communication with relevant stakeholders including healthcare professionals, policymakers, and patient advocacy groups. Based on the findings and identified insights, stakeholders can collaboratively design and implement interventions, programmes, or improvements in healthcare delivery that overcome the identified challenges directly and address and improve the overall patient experience. This cyclical process can hopefully produce research that not only informs but also leads to tangible improvements in healthcare practice and policy.

Patient journey mapping is typically a hands-on process, relying on surveys, interviews, and observational research. The technology that supports this research has, to date, included word processing software, and data analysis packages, such as NVivo, SPSS, and Stata. With the advent of more sophisticated technological tools, such as electronic health records, data analytics programmes, and patient tracking systems, healthcare providers and researchers can potentially use this technology to complement and enhance patient journey mapping research. 19 , 20 , 22 There are existing examples where technology has been harnessed in patient journey. Lee et al . used patient journey mapping to verify disease treatment data from the perspective of the patient, and then the authors developed a mobile prototype that organizes and visualizes personal health information according to the patient-centred journey map. They used a visualization approach for analysing medical information in personal health management and examined the medical information representation of seven mobile health apps that were used by patients and individuals. The apps provide easy access to patient health information; they primarily import data from the hospital database, without the need for patients to create their own medical records and information. 23

In another example, Wauben et al. 19 used radio frequency identification technology (a wireless system that is able to track a patient journey), as a component of their patient journey mapping project, to track surgical day care patients to increase patient flow, reduce wait times, and improve patient and staff satisfaction.

Patient journey mapping has emerged as a valuable research methodology in healthcare, providing a comprehensive and patient-centric approach to understanding the entire spectrum of a patient’s experience within the healthcare system. Future implications of this methodology are promising, particularly for transforming and redesigning healthcare delivery and improving patient outcomes. The impact may be most profound in the following key areas:

Personalized, patient-centred care : The methodology allows healthcare providers to gain deep insights into individual patient experiences. This information can be leveraged to deliver personalized, patient-centric care, based on the needs, values, and preferences of each patient, and aligned with guideline recommendations, healthcare professionals can tailor interventions and treatment plans to optimize patient and clinical outcomes.

Enhanced communication, collaboration, and co-design : Mapping patient interactions with health professionals and journeys within and across health services enables specific gaps in communication and collaboration to be highlighted and potentially informs responsive strategies for improvement. Ideally, these strategies would be co-designed with patients and health professionals, leading to improved care co-ordination and healthcare experience and outcomes.

Patient engagement and empowerment : When patients are invited to share their health journey experiences, and see visual or written representations of their journeys, they may come to understand their own health situation more deeply. Potentially, this may lead to increased health literacy, renewed adherence to treatment plans, and/or self-management of chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease. Given these benefits, we recommend that patients be provided with the findings of research and quality improvement projects with which they are involved, to close the loop, and to ensure that the findings are appropriately disseminated.

Patient journey mapping is an emerging field of research. Methods used in patient journey mapping projects have varied quite significantly; however, there are common research processes that can be followed to produce high-quality, insightful, and valuable research outputs. Insights gained from patient journey mapping can facilitate the identification of areas for enhancement within healthcare systems and inform the design of patient-centric solutions that prioritize the quality of care and patient outcomes, and patient satisfaction. Using patient journey mapping research can enable healthcare providers to forge stronger patient–provider relationships and co-design improved health service quality, patient experiences, and outcomes.

None declared.

Farmer J , Bigby C , Davis H , Carlisle K , Kenny A , Huysmans R , et al. The state of health services partnering with consumers: evidence from an online survey of Australian health services . BMC Health Serv Res 2018 ; 18 : 628 .

Google Scholar

Kelly J , Dwyer J , Mackean T , O’Donnell K , Willis E . Coproducing Aboriginal patient journey mapping tools for improved quality and coordination of care . Aust J Prim Health 2017 ; 23 : 536 – 542 .

Davies EL , Bulto LN , Walsh A , Pollock D , Langton VM , Laing RE , et al. Reporting and conducting patient journey mapping research in healthcare: a scoping review . J Adv Nurs 2023 ; 79 : 83 – 100 .

Ly S , Runacres F , Poon P . Journey mapping as a novel approach to healthcare: a qualitative mixed methods study in palliative care . BMC Health Serv Res 2021 ; 21 : 915 .

Arias M , Rojas E , Aguirre S , Cornejo F , Munoz-Gama J , Sepúlveda M , et al. Mapping the patient’s journey in healthcare through process mining . Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020 ; 17 : 6586 .

Natale V , Pruette C , Gerohristodoulos K , Scheimann A , Allen L , Kim JM , et al. Journey mapping to improve patient-family experience and teamwork: applying a systems thinking tool to a pediatric ambulatory clinic . Qual Manag Health Care 2023 ; 32 : 61 – 64 .

Cherif E , Martin-Verdier E , Rochette C . Investigating the healthcare pathway through patients’ experience and profiles: implications for breast cancer healthcare providers . BMC Health Serv Res 2020 ; 20 : 735 .

Gilburt H , Drummond C , Sinclair J . Navigating the alcohol treatment pathway: a qualitative study from the service users’ perspective . Alcohol Alcohol 2015 ; 50 : 444 – 450 .

Gichuhi S , Kabiru J , M’Bongo Zindamoyen A , Rono H , Ollando E , Wachira J , et al. Delay along the care-seeking journey of patients with ocular surface squamous neoplasia in Kenya . BMC Health Serv Res 2017 ; 17 : 485 .

Borycki EM , Kushniruk AW , Wagner E , Kletke R . Patient journey mapping: integrating digital technologies into the journey . Knowl Manag E-Learn 2020 ; 12 : 521 – 535 .

Barton E , Freeman T , Baum F , Javanparast S , Lawless A . The feasibility and potential use of case-tracked client journeys in primary healthcare: a pilot study . BMJ Open 2019 ; 9 : e024419 .

Bearnot B , Mitton JA . “You’re always jumping through hoops”: journey mapping the care experiences of individuals with opioid use disorder-associated endocarditis . J Addict Med 2020 ; 14 : 494 – 501 .

Cunnington MS , Plummer CJ , McDiarmid AK , McComb JM . The patient journey from symptom onset to pacemaker implantation . QJM 2008 ; 101 : 955 – 960 .

Geerse C , van Slobbe C , van Triet E , Simonse L . Design of a care pathway for preventive blood pressure monitoring: qualitative study . JMIR Cardio 2019 ; 3 : e13048 .

Laveau F , Hammoudi N , Berthelot E , Belmin J , Assayag P , Cohen A , et al. Patient journey in decompensated heart failure: an analysis in departments of cardiology and geriatrics in the Greater Paris University Hospitals . Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2017 ; 110 : 42 – 50 .

Naheed A , Haldane V , Jafar TH , Chakma N , Legido-Quigley H . Patient pathways and perceptions of treatment, management, and control Bangladesh: a qualitative study . Patient Prefer Adherence 2018 ; 12 : 1437 – 1449 .

Bateman S , Arnold-Chamney M , Jesudason S , Lester R , McDonald S , O’Donnell K , et al. Real ways of working together: co-creating meaningful Aboriginal community consultations to advance kidney care . Aust N Z J Public Health 2022 ; 46 : 614 – 621 .

Greenhalgh T , Hinton L , Finlay T , Macfarlane A , Fahy N , Clyde B , et al. Frameworks for supporting patient and public involvement in research: systematic review and co-design pilot . Health Expect 2019 ; 22 : 785 – 801 .

Wauben LSGL , Guédon ACP , de Korne DF , van den Dobbelsteen JJ . Tracking surgical day care patients using RFID technology . BMJ Innov 2015 ; 1 : 59 – 66 .

Tong A , Sainsbury P , Craig J . Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups . Int J Qual Health Care 2007 ; 19 : 349 – 357 .

von Elm E , Altman DG , Egger M , Pocock SJ , Gøtzsche PC , Vandenbroucke JP , et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies . Lancet 2007 ; 370 (9596): 1453 – 1457 .

Wilson A , Mackean T , Withall L , Willis EM , Pearson O , Hayes C , et al. Protocols for an Aboriginal-led, multi-methods study of the role of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers, practitioners and Liaison officers in quality acute health care . J Aust Indigenous HealthInfoNet 2022 ; 3 : 1 – 15 .

Lee B , Lee J , Cho Y , Shin Y , Oh C , Park H , et al. Visualisation of information using patient journey maps for a mobile health application . Appl Sci 2023 ; 13 : 6067 .

Author notes

- cardiovascular system

- health personnel

- health services

- health care systems

- narrative discourse

Email alerts

Related articles in pubmed, citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1873-1953

- Print ISSN 1474-5151

- Copyright © 2024 European Society of Cardiology

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Breast cancer patient experiences through a journey map: A qualitative study

Affiliations.

- 1 Clinical Psychology and Psychobiology Department, Faculty of Psychology, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

- 2 Medical Oncology Department Hospital Universitario Central of Asturias, Oviedo, Spain.

- 3 Social Psychology and Quantitative Psychology Department, Faculty of Psychology, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

- 4 Medical Oncology Department, Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos, Madrid, Spain.

- 5 Medical Oncology Department, Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense, Ourense, Spain.

- 6 Medical Oncology Department, Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid, Spain.

- 7 Medical Oncology Department, Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Elche, Spain.

- 8 Medical Oncology Department, Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón, Madrid, Spain.

- PMID: 34550996

- PMCID: PMC8457460

- DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257680

Background: Breast cancer is one of the most prevalent diseases in women. Prevention and treatments have lowered mortality; nevertheless, the impact of the diagnosis and treatment continue to impact all aspects of patients' lives (physical, emotional, cognitive, social, and spiritual).

Objective: This study seeks to explore the experiences of the different stages women with breast cancer go through by means of a patient journey.

Methods: This is a qualitative study in which 21 women with breast cancer or survivors were interviewed. Participants were recruited at 9 large hospitals in Spain and intentional sampling methods were applied. Data were collected using a semi-structured interview that was elaborated with the help of medical oncologists, nurses, and psycho-oncologists. Data were processed by adopting a thematic analysis approach.

Results: The diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer entails a radical change in patients' day-to-day that linger in the mid-term. Seven stages have been defined that correspond to the different medical processes: diagnosis/unmasking stage, surgery/cleaning out, chemotherapy/loss of identity, radiotherapy/transition to normality, follow-up care/the "new" day-to-day, relapse/starting over, and metastatic/time-limited chronic breast cancer. The most relevant aspects of each are highlighted, as are the various cross-sectional aspects that manifest throughout the entire patient journey.

Conclusions: Comprehending patients' experiences in depth facilitates the detection of situations of risk and helps to identify key moments when more precise information should be offered. Similarly, preparing the women for the process they must confront and for the sequelae of medical treatments would contribute to decreasing their uncertainty and concern, and to improving their quality-of-life.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Breast Neoplasms*

- Cross-Sectional Studies

- Neoplasm Recurrence, Local

- Qualitative Research

Grants and funding

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 04 December 2019

“Patient Journeys”: improving care by patient involvement

- Matt Bolz-Johnson 1 ,

- Jelena Meek 2 &

- Nicoline Hoogerbrugge 2

European Journal of Human Genetics volume 28 , pages 141–143 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

25k Accesses

18 Citations

25 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cancer genetics

- Cancer screening

- Cancer therapy

- Health policy

“I will not be ashamed to say ‘ I don’t know’ , nor will I fail to call in my colleagues…”. For centuries this quotation from the Hippocratic oath, has been taken by medical doctors. But what if there are no other healthcare professionals to call in, and the person with the most experience of the disease is sitting right in front of you: ‘ your patient ’.

This scenario is uncomfortably common for patients living with a rare disease when seeking out health care. They are fraught by many hurdles along their health care pathway. From diagnosis to treatment and follow-up, their healthcare pathway is defined by a fog of uncertainties, lack of effective treatments and a multitude of dead-ends. This is the prevailing situation for many because for rare diseases expertise is limited and knowledge is scarce. Currently different initiatives to involve patients in developing clinical guidelines have been taken [ 1 ], however there is no common method that successfully integrates their experience and needs of living with a rare disease into development of healthcare services.

Even though listening to the expertise of a single patient is valuable and important, this will not resolve the uncertainties most rare disease patients are currently facing. To improve care for rare diseases we must draw on all the available knowledge, both from professional experts and patients, in order to improve care for every single patient in the world.

Patient experience and satisfaction have been demonstrated to be the single most important aspect in assessing the quality of healthcare [ 2 ], and has even been shown to be a predictor of survival rates [ 3 ]. Studies have evidenced that patient involvement in the design, evaluation and designation of healthcare services, improves the relevance and quality of the services, as well as improves their ability to meet patient needs [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]. Essentially, to be able to involve patients, the hurdles in communication and initial preconceptions between medical doctors and their patients need to be resolved [ 7 ].

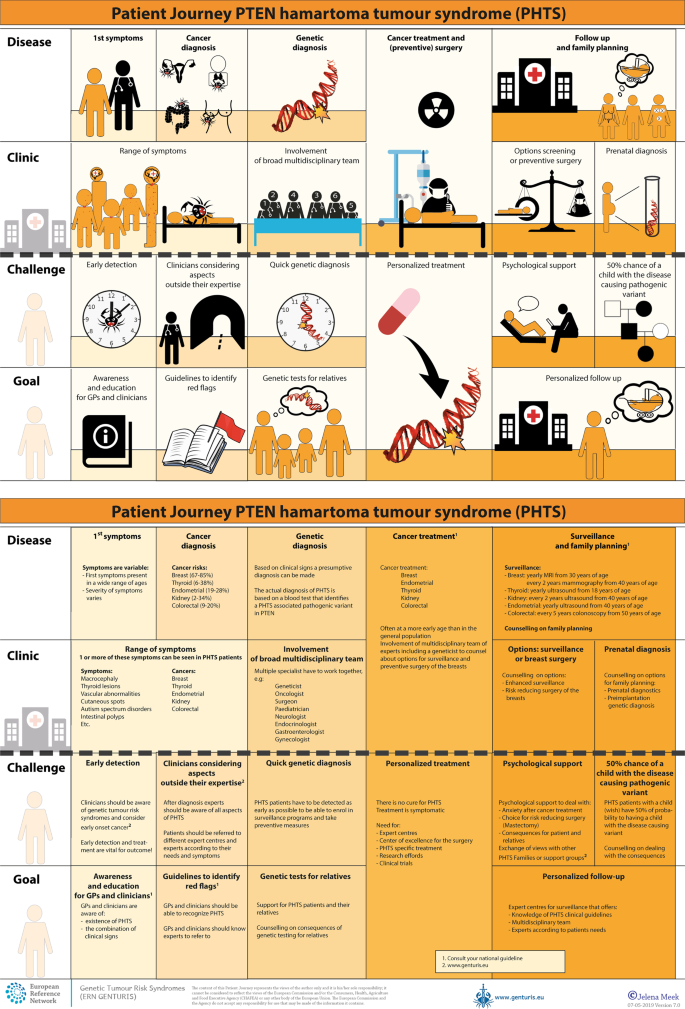

To tackle the current hurdles in complex or rare diseases, European Reference Networks (ERN) have been implemented since March 2017. The goal of these networks is to connect experts across Europe, harnessing their collective experience and expertise, facilitating the knowledge to travel instead of the patient. ERN GENTURIS is the Network leading on genetic tumour risk syndromes (genturis), which are inherited disorders which strongly predispose to the development of tumours [ 8 ]. They share similar challenges: delay in diagnosis, lack of cancer prevention for patients and healthy relatives, and therapeutic. To overcome the hurdles every patient faces, ERN GENTURIS ( www.genturis.eu ) has developed an innovative visual approach for patient input into the Network, to share their expertise and experience: “Patient Journeys” (Fig. 1 ).

Example of a Patient Journey: PTEN Hamartoma Tumour Syndrome (also called Cowden Syndrome), including legend page ( www.genturis.eu )

The “Patient Journey” seeks to identify the needs that are common for all ‘ genturis syndromes ’, and those that are specific to individual syndromes. To achieve this, patient representatives completed a mapping exercise of the needs of each rare inherited syndrome they represent, across the different stages of the Patient Journey. The “Patient Journey” connects professional expert guidelines—with foreseen medical interventions, screening, treatment—with patient needs –both medical and psychological. Each “Patient Journey” is divided in several stages that are considered inherent to the specific disease. Each stage in the journey is referenced under three levels: clinical presentation, challenges and needs identified by patients, and their goal to improve care. The final Patient Journey is reviewed by both patients and professional experts. By visualizing this in a comprehensive manner, patients and their caregivers are able to discuss the individual needs of the patient, while keeping in mind the expertise of both professional and patient leads. Together they seek to achieve the same goal: improving care for every patient with a genetic tumour risk syndrome.

The Patient Journeys encourage experts to look into national guidelines. In addition, they identify a great need for evidence-based European guidelines, facilitating equal care to all rare patients. ERN GENTURIS has already developed Patient Journeys for the following rare diseases ( www.genturis.eu ):

PTEN hamartoma tumour syndrome (PHTS) (Fig. 1 )

Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC)

Lynch syndrome

Neurofibromatosis Type 1

Neurofibromatosis Type 2

Schwannomatosis

A “Patient Journey” is a personal testimony that reflects the needs of patients in two key reference documents—an accessible visual overview, supported by a detailed information matrix. The journey shows in a comprehensive way the goals that are recognized by both patients and clinical experts. Therefore, it can be used by both these parties to explain the clinical pathway: professional experts can explain to newly identified patients how the clinical pathway generally looks like, whereas their patients can identify their specific needs within these pathways. Moreover, the Patient Journeys could serve as a guide for patients who may want to write, in collaboration with local clinicians, diaries of their journeys. Subsequently, these clinical diaries can be discussed with the clinician and patient representatives. Professionals coming across medical obstacles during the patient journey can contact professional experts in the ERN GENTURIS, while patients can contact the expert patient representatives from this ERN ( www.genturis.eu ). Finally, the “Patient Journeys” will be valuable in sharing knowledge with the clinical community as a whole.

Our aim is that medical doctors confronted with rare diseases, by using Patient Journeys, can also rely on the knowledge of the much broader community of expert professionals and expert patients.

Armstrong MJ, Mullins CD, Gronseth GS, Gagliardi AR. Recommendations for patient engagement in guideline development panels: a qualitative focus group study of guideline-naive patients. PloS ONE 2017;12:e0174329.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gupta D, Rodeghier M, Lis CG. Patient satisfaction with service quality as a predictor of survival outcomes in breast cancer. Supportive Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc Supportive Care Cancer. 2014;22:129–34.

Google Scholar

Gupta D, Lis CG, Rodeghier M. Can patient experience with service quality predict survival in colorectal cancer? J Healthc Qual Off Publ Natl Assoc Healthc Qual. 2013;35:37–43.

Sharma AE, Knox M, Mleczko VL, Olayiwola JN. The impact of patient advisors on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:693.

Fonhus MS, Dalsbo TK, Johansen M, Fretheim A, Skirbekk H, Flottorp SA. Patient-mediated interventions to improve professional practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;9:Cd012472.

PubMed Google Scholar

Cornman DH, White CM. AHRQ methods for effective health care. Discerning the perception and impact of patients involved in evidence-based practice center key informant interviews. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2017.

Chalmers JD, Timothy A, Polverino E, Almagro M, Ruddy T, Powell P, et al. Patient participation in ERS guidelines and research projects: the EMBARC experience. Breathe (Sheff, Engl). 2017;13:194–207.

Article Google Scholar

Vos JR, Giepmans L, Rohl C, Geverink N, Hoogerbrugge N. Boosting care and knowledge about hereditary cancer: european reference network on genetic tumour risk syndromes. Fam Cancer 2019;18:281–4.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

This work is generated within the European Reference Network on Genetic Tumour Risk Syndromes – FPA No. 739547. The authors thank all ERN GENTURIS Members and patient representatives for their work on the Patient Journeys (see www.genturis.eu ).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

SquareRootThinking and EURORDIS – Rare Diseases Europe, Paris, France

Matt Bolz-Johnson

Human Genetics, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Jelena Meek & Nicoline Hoogerbrugge

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nicoline Hoogerbrugge .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Bolz-Johnson, M., Meek, J. & Hoogerbrugge, N. “Patient Journeys”: improving care by patient involvement. Eur J Hum Genet 28 , 141–143 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0555-6

Download citation

Received : 07 August 2019

Revised : 04 October 2019

Accepted : 01 November 2019

Published : 04 December 2019

Issue Date : February 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0555-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Care trajectories of surgically treated patients with a prolactinoma: why did they opt for surgery.

- Victoria R. van Trigt

- Ingrid M. Zandbergen

- Nienke R. Biermasz

Pituitary (2023)

Designing rare disease care pathways in the Republic of Ireland: a co-operative model

- E. P. Treacy

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2022)

Rare disease education in Europe and beyond: time to act

- Birute Tumiene

- Harm Peters

- Gareth Baynam

Development of a patient journey map for people living with cervical dystonia

- Monika Benson

- Alberto Albanese

- Holm Graessner

Der klinische Versorgungspfad zur multiprofessionellen Versorgung seltener Erkrankungen in der Pädiatrie – Ergebnisse aus dem Projekt TRANSLATE-NAMSE

- Daniela Choukair

- Min Ae Lee-Kirsch

- Peter Burgard

Monatsschrift Kinderheilkunde (2022)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Open access

- Published: 04 September 2021

Journey mapping as a novel approach to healthcare: a qualitative mixed methods study in palliative care

- Stephanie Ly 1 ,

- Fiona Runacres 1 , 2 , 3 &

- Peter Poon 1 , 2

BMC Health Services Research volume 21 , Article number: 915 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

16 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

Journey mapping involves the creation of visual narrative timelines depicting the multidimensional relationship between a consumer and a service. The use of journey maps in medical research is a novel and innovative approach to understanding patient healthcare encounters.

To determine possible applications of journey mapping in medical research and the clinical setting. Specialist palliative care services were selected as the model to evaluate this paradigm, as there are numerous evidence gaps and inconsistencies in the delivery of care that may be addressed using this tool.

A purposive convenience sample of specialist palliative care providers from the Supportive and Palliative Care unit of a major Australian tertiary health service were invited to evaluate journey maps illustrating the final year of life of inpatient palliative care patients. Sixteen maps were purposively selected from a sample of 104 consecutive patients. This study utilised a qualitative mixed-methods approach, incorporating a modified Delphi technique and thematic analysis in an online questionnaire.

Our thematic and Delphi analyses were congruent, with consensus findings consistent with emerging themes. Journey maps provided a holistic patient-centred perspective of care that characterised healthcare interactions within a longitudinal trajectory. Through these journey maps, participants were able to identify barriers to effective palliative care and opportunities to improve care delivery by observing patterns of patient function and healthcare encounters over multiple settings.

Conclusions

This unique qualitative study noted many promising applications of the journey mapping suitable for extrapolation outside of the palliative care setting as a review and audit tool, or a mechanism for providing proactive patient-centred care. This is particularly significant as machine learning and big data is increasingly applied to healthcare.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Patterns of healthcare utilisation are evolving in response to the ageing population and increasing burden of chronic disease. There is an urgent need to ensure timely proactive medical care, effective and efficient resource deployment, while averting unnecessary, often distressing, emergency department (ED) presentations, admissions and conveyor belt medicine. A key area of medicine able to address these issues is palliative care.

Central to optimal delivery of palliative care is timely initiation [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. However, differing patient, illness trajectory and clinical factors have resulted in inconsistencies in the degree of care provided [ 4 , 5 ]. This has subsequently translated into significant variability in palliative care research and limitations in applying international evidence to clinical practice [ 6 ]. The utilisation of journey mapping has the potential to address these inconsistencies and to our knowledge, this research is the first of its kind.

Journey mapping is a relatively new approach in medical research that has been adapted from customer service and marketing research [ 7 ]. It is gaining increasing recognition for its ability to organise complex multifaceted data from numerous sources and explore interactions across care settings and over time. Medical journey mapping involves creating narrative timelines, by incorporating markers of the patient experience with healthcare service encounters. Integrating diverse components of the patient healthcare journey provides a holistic perspective of the relationships between the different elements that may guide directions for change and service improvement. As medical journey mapping is still in its infancy, there is an absence of literature exploring implementation. Of the existing literature, journey mapping techniques are described mainly in process papers, outlining their potential utility in observing healthcare delivery and patient outcomes [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. However journey mapping paradigms have broader significance across healthcare, especially in an environment for which machine learning, big data and artificial intelligence is maturing.

We aimed to determine whether journey mapping could contribute to the improvement of patient-centred medical research in a palliative care setting and provide new insight into possible “pivot-points” or moments of care that could be altered to improve care delivery. Specifically, we sought to determine whether journey maps were able to assist in capturing a holistic, longitudinal and more integrative patient history whilst outlining healthcare provision and identifying gaps in care.

Study design

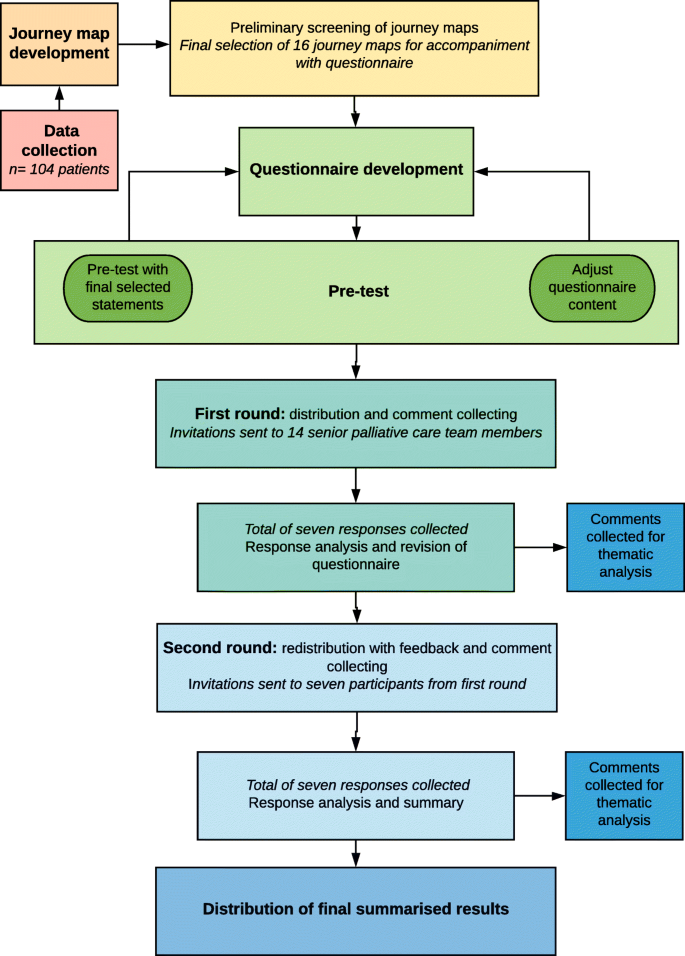

We performed a qualitative mixed-methods analysis of a journey mapping tool. The tool was purpose-developed and sample journey maps were derived from the scanned medical records of palliative care patients. A panel of specialist palliative care providers were then involved in an online questionnaire combining a modified Delphi approach with inductive thematic analysis. Figure 1 depicts a flow diagram of the methodology.

Flow chart detailing data collection, journey map development and analysis. This figure illustrates the phases and processes of this study. Data was collected from a retrospective cohort of 104 palliative care patients and journey maps were subsequently developed. Preliminary screening of the journey maps was performed to obtain a purposive sample that best highlighted the breadth of information and healthcare encounters captured within the journey maps. A total of 16 maps were selected for further analysis. Following questionnaire development and pre-test, questionnaires were distributed, and responses collected and analysed over two rounds to obtain consensus. Free-text comments from both rounds were collected for thematic analysis

All methods were carried out and reported in accordance with Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) guidelines and Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research (COREQ) criteria for reporting qualitative studies.

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from Monash Health Human Research Ethics Committee Monash Health Ref: RES-29-0000-071Q) and Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID: 18,853).

Data was collected from a retrospective cohort of 104 consecutive palliative care patients from a major tertiary hospital network in Melbourne, Australia. Inclusion criteria were patients greater than 18 years of age who had died in hospital between the 1st of August 2018 and 31st of October 2018, had at least one inpatient palliative care admission in their last year of life and scanned medical records data spanning at least three months’ duration. This sample size was considered sufficient to incorporate a varied and representative sample of palliative care patients encountered in the tertiary hospital.

Following data collection, a Python Software-based code was designed to extract de-identified data and create journey map visuals. All 104 journey maps were independently screened by two investigators (PP and FR) and a purposive sample of 16 maps was selected for analysis based on seven criteria for informative value. The criteria that the 104 maps were assessed on included their ability to provide insight into the initiation, triggers, delivery and barriers of palliative care, SPICT scores, pivot points and disease trajectories.

Modified Delphi approach and thematic analysis

A qualitative mixed-methods approach involving thematic analysis and a modified Delphi technique was utilised as an explorative analysis of expert opinion. The consensus agreement was used to reinforce and confirm the patterns of significance identified through thematic analysis. In combining these two approaches, there was greater flexibility in responses and additional structure to support analysis.

The modified Delphi approach used in this study was adapted from the enhanced Delphi method described by Yang et al. [ 13 ] and consisted of a questionnaire pre-test and two rounds of questionnaire distribution. A total of 14 email invitations were sent to a purposive sample of seven senior palliative care physicians and seven palliative care nurse consultants across two palliative care inpatient units within a major tertiary hospital network in Melbourne, Australia. The emails contained an explanatory statement, a questionnaire link and the file containing the 16 de-identified journey maps.

The questionnaires consisted of 16 statements per journey map, covering eight palliative care domains: palliative care triggers, initiation, delivery, outcomes, barriers, pivot-points, needs assessment (using the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool, SPICT) and the utility of advanced care plans. An additional nine statements assessed the utility of the journey map approach (see Table 2 ). All statements were ranked using Likert scales. A four-point Likert scale including the options: insufficient information, disagree, neither agree nor disagree and agree was used to assess individual journey maps. A five-point Likert scale including options: strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat agree and strongly agree was used to assess the journey mapping approach. For analysis of consensus, the results were categorised to reflect overall agreement by using a three-point scale consisting of disagree, neutral and agree . Consensus was defined as agreement of greater than 70 % of respondents in any one of these three categories. Following the first round, all consensus statements were determined and participants were sent a second questionnaire containing anonymous feedback from the first round and statements which did not reach consensus for re-evaluation using the condensed three-point Likert scale.

Following each palliative care domain, free-text fields were included to collect comments and provide data for inductive thematic analysis. Analysis of the free-text comments from both rounds was guided by Braun and Clarke’s phases of thematic analysis [ 14 ]. The codes and themes were derived from the data using NVivo 12 Plus software to generate nodes, initial codes and preliminary subthemes. Candidate themes were reviewed by two additional investigators (PP and FR) to ensure consistency and the final themes were defined. Providing participants with the opportunity to review de-identified feedback through the Delphi questionnaire enabled discussion, reflection and clarification of comments, thus achieving thematic saturation with a smaller group of participants.

Additional steps were taken to increase trustworthiness of the qualitative data per Lincoln and Guba’s criteria for credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability across all phases of analysis [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Triangulation of the methods, researchers and analysts aimed to increase consistency and accuracy, whilst reducing interpretation errors and the effects of bias. Thorough audit trails and reflexive journaling were maintained. The use of the online questionnaire with free-text fields for thematic data collection limited the role of the researcher and the potential for associated bias.

While this study also produced findings relevant to current issues of palliative care delivery, we will for the purpose of this paper, present results specific to the clinical utility of journey maps.

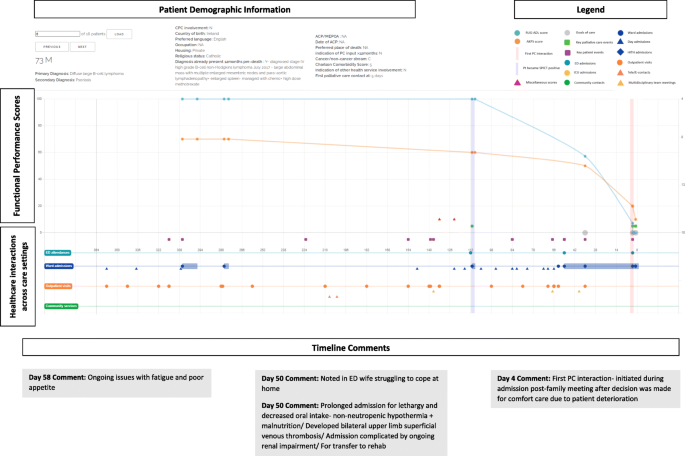

The journey maps

Figure 2 depicts one of the 16-sample journey maps analysed by participants and illustrates the key elements of a map. While journey maps are interactive visualisations with options for providing additional information summarising patient healthcare encounters, we are unable to fully convey the dynamic functions of the mapping tool in this paper. The journey map in Fig. 2 illustrates the final year of life of a 73 year old male patient with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Screen capture of Journey Map 6. A screen capture of one of the 16 interactive journey maps that was analysed by the Delphi panel. The lower segment of the map depicts healthcare interactions that occurred in hospital and in the community. Delphi participants are able to hover over specific health service touch points to obtain more information about the specific interaction that occurred. The upper segment represents functional performance scores using two different tools- the Australian Karnofsky Performance Scale (AKPS) and the Resource Utilisation Groups-Activities of Daily Living (RUG-ADL). The orange vertical line indicates when palliative care needs first presented using the SPICT screening tool. The vertical purple line indicates when specialist palliative care was initiated. Delphi participants were able to analyse the maps and respond to statements on the palliative care provided

The map reveals that at day 112 prior to death, palliative care needs were noted using the SPICT screening tool. It is also at this point that the patient’s functional performance scores began to decline, with patient notes from day admissions and clinic visits also documenting poor tolerance of chemotherapy side effects, fatigue, anorexia and weight loss. In response to this pattern of decline, participants noted that there was an opportunistic role for community palliative care support that was missed and could have potentially negated the need for the final ED admission.

“Onc (sic)(oncology) outpatient notes describing symptoms, deterioration, carer distress… Community pall care (sic)(palliative care) could have been helpful” – Participant 2, Journey Map (JM) 6.

Another major pivot-point occurred during the patient’s admission to ED on day 50 when notes indicated that the patient’s wife was struggling to cope with care at home. Given the nature of the prolonged admission with multiple complications that followed, Delphi participants questioned the suitability of the transfer to the rehabilitation ward.

“Symptoms and functional decline appear to be related to lymphoma and not an acute illness. More appropriate for pall care (sic) than rehab (sic)(rehabilitation).” – Participant 6, JM6.

Additionally, the decision to initiate palliative care only four days prior to death was delayed and there was a role for earlier palliative care involvement.

“Clearly PC (sic)(palliative care) involvement inadequate and was a later referral for terminal care only” – Participant 1, JM6.

“Pt (sic)(patient) would have benefitted from earlier palliative care referral” – Participant 7, JM6.

Through the maps, participants were able to observe patterns of deterioration with a broader view of continuity of care and determine pivot-points, where the involvement of specialist palliative care had the potential to improve the patient experience.

Modified Delphi

The two Delphi rounds were conducted over 31 days with the first round taking 13 days and the second round spanning 18 days. A total of seven responses were collected from the first round of the online Delphi questionnaire. Six members of the medical staff and one member of the nursing team responded, representing a 50 % response rate. All seven participants completed the questionnaire in full. For the second round, all first round participants were re-contacted and invited to participate. All seven participants from the first round agreed to participate, attributing to a 100 % second round response rate and 100 % questionnaire completion rate. Participant characteristics have been described in Table 1 . All participants are senior palliative care team members.

The statements assessing journey map utility are shown in Table 2 . As there was a strong overall consensus following the first round of the Delphi questionnaire, these statements were not rechallenged in a second round. However free-text fields were included to allow participants to provide any further comments.

Thematic analysis

Following analysis of all free-text comments, the following themes were derived regarding the applications of the journey mapping tool: (1) design and information, (2) longitudinal care and the patient trajectory and (3) opportunities for care improvement. These are discussed with supporting quotations listed in Table 3 .

Theme 1: tool design and information

A large determinant of the practicality of the tool relates to its design. Participants provided feedback regarding the design and informational elements of the journey mapping tool used in this study.

Aspects of the interface

Participants found that there were certain elements of the journey maps that limited functionality of the tool, however these were associated with the specific design of the tool interface, rather than the actual components underlying the journey mapping approach. Participants responded well to the concept of a visual representation of patient information and the timeline view of care that was constructed.

Catering information needs

Given the palliative care specific focus on patient care presented in these maps, participants found that at times there was an excess of unnecessary information and insufficient palliative care appropriate information. The absence of objective measures of quality of life also restricted the ability of participants to determine whether outcomes were improved as a result of interventions.

Theme 2: Longitudinal care and the patient trajectory

The benefits of conveying patient information and healthcare encounters in the form of journey maps were also recognised. Journey maps provided a patient-centred focus of care that characterises patient healthcare interactions within a longitudinal trajectory rather than individual care episodes as is standard in conventional medical records. In doing so, patterns of the disease trajectory and also patient decline can be mapped to provide more proactive patient care.

Theme 3: Opportunities for care improvement

The benefits of having the journey mapping tool and its utility if incorporated into patient care were also explored, with participants noting numerous possible applications and opportunities to improve patient care.

Identifying barriers and missed opportunities for care

By framing the patient healthcare experience as a longitudinal and continuous journey, participants were able to recognise missed opportunities to address barriers and initiate more timely palliative care.

Clinical applications

Participants also noted that journey maps were a useful tool for identifying gaps in care provision and underlying barriers to initiation and delivery. This could assist clinicians with recognition of pivot-points and opportunities to enhance care by pre-emptively managing issues. Additionally, journey maps presented possible applications as a review or screening tool to evaluate patient care needs and enable better patient-centred care practices both in the clinical and research setting.

Findings from both the modified Delphi and thematic analysis appeared congruent, with the consensus consistent with emerging themes.

Journey mapping is a novel approach to reviewing patient healthcare interactions over time and across care settings to identify potential pivot points, which in turn can facilitate timely healthcare and promote proactive delivery of patient-centred care. Our research has focused on palliative care as the model to explore this approach, especially given its importance in an ageing population and considering many aspects of care are ubiquitous to this cohort.

Variation and inconsistencies in palliative care initiation and delivery have limited the applicability and role of research in informing evidence-based practice [ 6 ]. A journey map approach may provide one solution to address these challenges. The journey mapping tool used in this study was found to enable a patient-centred focus to the clinician’s perspective, increasing opportunities to pro-actively identify pivot-points and deliver more effective patient care.

In comparison to conventional medical records, journey maps link patient healthcare encounters longitudinally, promoting continuity and a holistic understanding of care across settings and over time. As described in conceptual studies, journey maps offer a perspective that takes into account the more dynamic and multidimensional aspects of healthcare interactions to facilitate enhanced insight into the patient experience within medical research [ 10 , 18 ]. This enables a more integrated interpretation and awareness of individual episodes of care and how these contribute to a patient’s overall health and their interaction with health services. Our participants also noted that journey mapping enabled greater emphasis on particular patient outcomes that may be difficult to observe or measure using conventional research methods. The journey mapping tool was also able to highlight gaps in care and facilitate recognition of patterns of disease progression and deterioration with a greater emphasis on patient needs and experiences.

The use of the journey mapping approach has further enabled identification of barriers and potential biases to providing effective care. This study confirms that journey mapping as a tool is effective at identifying specific barriers and trends in care provision and increase opportunities for care providers to pro-actively and appropriately address these.

Journey maps have traditionally been used in research to review and analyse the consumer experience and provide feedback on avenues for development [ 7 ]. Our panel consensus affirmed that journey mapping had applications as a clinical audit tool to identify gaps in care and opportunities for improvement when used to assess retrospective patient experiences. This is consistent with known utilities of previous journey mapping tools. Other identified benefits included potential to achieve better collaboration between healthcare providers, enabling smoother transitions of care and improving communication between healthcare providers and patients.

Limitations of this study include the design and interface of the journey mapping tool. Following a thorough search, pre-existing journey mapping software and tools were considered inappropriate for this study as they were oversimplified, unable to convey complex information appropriately and not designed for use in a medical setting. Consequently, self-designing a tool was considered the most suitable approach. The technical limitations identified did not reflect the utility of the journey mapping paradigm.

The retrospective nature of this study prohibits direct patient feedback. Consequently, the patient and caregiver perspective, including quality of life and symptom burden experienced were not well represented. Future research utilising a prospective approach with patient and caregiver involvement is needed to address these research gaps.

The response rate to the initial Delphi questionnaire was only 50 % due to time constraints and limited ability to accommodate delayed responses, however the response rate to the second Delphi questionnaire was 100 %. While this does limit the diversity of responses, it suggests good retention and engagement of involved participants with meaningful contributions.

The size of the Delphi panel in this study was seven. Studies have noted that smaller panels are still able to provide effective and reliable results and a minimum panel size of seven is considered suitable in most cases [ 19 , 20 ]. Our modified approach complied with this. Despite being a single institution study, the participants come from a diverse clinical background covering multiple domains of specialty palliative care, henceforth reducing potential bias. This study demonstrates that there is a role for journey mapping in clinical practice, however, considerations must be made for future design. Given the volume of patient data available, the amount of information presented needs to be appropriately moderated to provide clarity and best utilisation of the resources available. With the gradual transition of most health services from paper medical records to electronic medical records, the inclusion of a journey mapping tool into clinical practice is becoming more feasible. As medical technology continues to grow, the potential for incorporation of artificial intelligence, machine learning and big data into journey maps could be the key to providing pro-active, holistic patient-centred care that pre-emptively anticipates patient needs.

This study is one of the first to use a journey mapping tool in clinical practice to explore the healthcare journey and patient experience on a larger scale. The maps were used to depict a more fluid and continuous interpretation of the patient healthcare experience which enabled a more holistic and patient-centred analysis of palliative care provision. Furthermore, this is one of the first medical journey mapping studies to consider and propose potential pivot-points and opportunities for changes in the delivery of care. The use of journey maps can enhance the holistic patient healthcare experience and enable better patient-centred care not only in the palliative care setting, but also more broadly across healthcare from both a research and clinical practice perspective. Further application studies in other contexts are required.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the confidential nature of the patient data, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–42.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, et al. Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(13):1438–45.

Article Google Scholar

King JD, Eickhoff J, Traynor A, Campbell TC. Integrated onco-palliative care associated with prolonged survival compared to standard care for patients with advanced lung cancer: a retrospective review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(6):1027–32.

Hawley P. Barriers to access to palliative care. Palliative Care. 2017;10:1178224216688887.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rodriguez KL, Barnato AE, Arnold RM. Perceptions and utilization of palliative care services in acute care hospitals. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(1):99–110.

Evans CJ, Harding R, Higginson IJ. Morecare. ‘Best practice’ in developing and evaluating palliative and end-of-life care services: a meta-synthesis of research methods for the MORECare project. Palliat Med. 2013;27(10):885–98.

Gibbons S. Journey Mapping 101. 2018; https://www.nngroup.com/articles/journey-mapping-101/ .

Crunkilton DD. Staff and client perspectives on the Journey Mapping online evaluation tool in a drug court program. Eval Program Plan. 2009;32(2):119–28.

Westbrook JI, Coiera EW, Sophie Gosling A, Braithwaite J. Critical incidents and journey mapping as techniques to evaluate the impact of online evidence retrieval systems on health care delivery and patient outcomes. Int J Med Inform. 2007;76(2–3):234–45.

McCarthy S, O’Raghallaigh P, Woodworth S, Lim YL, Kenny LC, Adam F. An integrated patient journey mapping tool for embedding quality in healthcare service reform. J Decision Syst. 2016;25(sup1):354–68.

Hide E, Pickles J, Maher L. Experience based design: a practical method of working with patients to redesign services. Clin Gov. 2008;13(1):51–8.

Trebble TM, Hansi N, Hydes T, Smith MA, Baker M. Process mapping the patient journey: an introduction. BMJ. 2010;341:c4078.

Yang T-H. Case study: application of enhanced Delphi method for software development and evaluation in medical institutes. Kybernetes. 2016;45(4):637–49.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16(1):1609406917733847.

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1985.

Book Google Scholar

Cohen D, Crabtree B. Qualitative Research Guidelines Project. 2006; http://www.qualres.org/HomeRefl-3703.html .

Ben-Tovim DI, Dougherty ML, O’Connell TJ, McGrath KM. Patient journeys: the process of clinical redesign. Med J Aust. 2008;188(S6):S14–7.

PubMed Google Scholar

Linstone H. The Delphi technique. Handbook of Futures Research. Westport: Greenwood; 1978.

Google Scholar

Akins RB, Tolson H, Cole BR. Stability of response characteristics of a Delphi panel: application of bootstrap data expansion. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:37–37.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and extend our thanks to Kevin Shi who contributed to the Python code used for the journey map visuals.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Medicine Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Clayton, VIC, Australia

Stephanie Ly, Fiona Runacres & Peter Poon

Supportive & Palliative Care Department, McCulloch House, Monash Medical Centre, 246 Clayton Road, VIC, 3168, Clayton, Australia

Fiona Runacres & Peter Poon

Calvary Health Care Bethlehem, Parkdale, VIC, Australia

Fiona Runacres

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conceptualisation PP. Methodology: PP, FR, SL. Formal analysis PP, FR, SL. Investigation: PP, FR, SL. Writing –original draft: SL. Writing- Review and Editing: PP, FR. Supervision : PP, FR. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Peter Poon .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from Monash Health Human Research Ethics Committee Monash Health Ref: RES-29-0000-071Q) and Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID: 18853). Informed consent from patients was not required as this was a retrospective audit of pre-existing available data which was de-identified prior to analysis. All participants of the Delphi questionnaire were provided with an explanatory statement and by completing and returning the questionnaires, consent was implied.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ly, S., Runacres, F. & Poon, P. Journey mapping as a novel approach to healthcare: a qualitative mixed methods study in palliative care. BMC Health Serv Res 21 , 915 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06934-y

Download citation

Received : 10 April 2021

Accepted : 24 August 2021

Published : 04 September 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06934-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Patient journey mapping

- Health services research

- Palliative care

- Illness trajectory

- Proactive healthcare

- Medical informatics

- Patient-centred care

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Resource Library

.png?width=500&height=500&name=Mapping%20the%20Patient%20Journey%20(circle).png)

Mapping the Patient Journey

Visualizing the decentralized clinical trials patient experience to appreciate the journey of the research participant.

Description of the Patient Journey Map

These patient journey maps are designed to enhance the clinical research experience for stakeholders such as sponsors, CROs, and sites involved in global decentralized clinical trials (DCTs). These visual representations depict the patient's journey across various research phases and indications. This offers a more comprehensive, patient-focused understanding of the decentralized process. By incorporating the patient's perspective, our maps aim to minimize barriers and patient burden. This increases the likelihood of completing studies on time and within budget, with increased patient retention and protocol compliance.

Study team members can use the foundation of these visualizations to create tailored DCT patient journeys. These are examples to help support you as you develop your trial’s ideal patient journey, using the templates provided. Keep in mind that each patient's experience is unique, as demonstrated by example journey maps from oncology and rare disease trials.

Research Methods

The journeys depicted here are a result of conversations with multiple patients representative of the disease states being depicted, as well as lessons learned from industry leaders in decentralized and hybrid clinical trial conduct.

These visualizations will make it easier to understand and contextualize the decentralized patient journey across multiple phases of research and indications of interest. In the near future, you will be able to use the work behind these outputs to map out your own DCT patient journeys.

Download the Patient Journey Map Template

Oncology, rare disease, and rsv vaccine studies.

These therapeutic areas were chosen because oncology represents the largest proportion of clinical trials being conducted, rare disease is a rapidly expanding area of development, and RSV vaccines are pushing new frontiers in preventive healthcare.

While DCT isn't right for every trial, by thoughtfully incorporating elements as appropriate, we have the power to democratize research and bring clinical trials to members of the population typically underrepresented in trials.

These journey maps—the Oncology Journey Map, the Rare Disease Journey Map, and the RSV Vaccine Journey Map—are available for download below. Review these journey maps and incorporate the lessons learned into your own patient journey-mapping initiatives.

google docs viewer

This browser does not support inline PDFs. Please download the PDF to view it: Download PDF .

Patient Journey Map Feedback

Download the full initiative charter, relevant resources.

December 10, 2020 DECENTRALIZED TRIALS & RESEARCH ALLIANCE (DTRA) LAUNCHES TO DEMOCRATIZE AND ACCELERATE CLINICAL TRIALS

December 1, 2021 One Year In, DTRA Meets Goals & Looks To The Future