DPC Frontier

Journey Direct Primary Care (FreedomDOC)

Direct primary care in hoover, al.

Accepting new patients

Family Medicine

Meet the doctor

John shugrue, md, prices and fees.

Membership prices

$240/MONTH Family max (for Family of 5 and over)

Additional fees

Enrollment fee

What is Direct Primary Care?

Direct Primary Care, or DPC, is a new way of providing primary care that's already helped a quarter million people stay healthier and spend less on healthcare. Patients at DPC practices often receive ongoing primary care from their doctor with zero copays, convenient online scheduling options, near-wholesale prices on medications and blood tests, and even their doctor's personal cell number. It's like having a doctor in the family.

So how is this possible? Easy: direct primary care practices cut out middlemen like insurance companies, freeing themselves to provide great care at fair prices. Unlike traditional third party practices that serve the needs of insurance companies, direct primary care is for everybody; most DPC memberships cost less than your monthly cell phone or cable bill, for great care whenever you need it.

If you're tired of high copays, insane wait times, rushed 8-minute doctor visits, join 250,000 other Americans that have already benefited from direct primary care. Search on the DPC Mapper to find a practice near you.

Founded by Phil Eskew. Copyright © 2018 by DPC Frontier, LLC All rights reserved.

now accepting new patients! *Same day, late evening, & saturday appointments!

NOW ACCEPTING NEW PATIENTS!

*walk-in/same day, late evening & saturday appointments available.

Now Offering On Site Echocardiogram, Non-Invasive Cardiovascular Wellness Scan, Arterial/Doppler and Ultrasound services!

Here to leave a review? Scroll down to the "Review" section and click the Google hyperlink.

"on your journey to becoming your whole self, we're here beside you every step of the way...", our philosophy.

At JourneyCare Family Medicine, we believe in treating the whole person-not just their symptoms. We take a holistic approach to healthcare, focusing on the physical, mental, and emotional well-being of our patients. With our unique mixture of Family Medicine, Holistic Medicine, Mental Health services and extended hours (we're even open on Saturday), we are not just a primary care clinic; we are a "patient centered medical home" which prioritizes the needs of our patients above all.

Affordable, High-Quality Healthcare for Your Entire Family!

*LATE EVENING & SATURDAY APPOINTMENTS AVAILABLE*

A Personal Approach

Experienced medical professionals.

Whether you need medical care for acute illnesses, chronic diseases, or disease prevention, our team has the professional experience to realize that there is no such thing as "one-size-fits-all". When it comes to your treatment plan, our approach is individualized to your meet your specific needs.

Our team is highly skilled, knowledgeable, and compassionate, and is dedicated to improving and maintaining your overall health by empowering you to understand and manage your health conditions and wellness plan.

The Latest Treatments

We provide both a high-quality and personalized health experience by offering a broad array of medical care services. We offer the latest evidence-based treatments and technology to address common illnesses and injuries. We are dedicated to improving your health through preventative care and management of chronic diseases.

most commercial insurance plans, Medicaid, and MEdicare accepted!

Patient-centered care.

At JourneyCare Family Medicine, we pride ourselves on providing patient-centered care. We listen to your concerns, answer your questions, and work with you to develop a treatment plan that meets your specific needs. We are dedicated to ensuring your satisfaction with the care you receive.

New Patients

We are happily accepting new patients at JourneyCare Family Medicine! We offer late evening, * same and/or next day , and Saturday appointments! If you're looking for a new healthcare provider, we would be honored to serve you and your family. Contact us today to schedule your first appointment! *Same and/or next day appointments are based on scheduling availability.

Chronic Disease Management

If you're living with a chronic condition, we can help you manage it and improve your quality of life. Find out how we can support you.

Pediatric Care

We provide comprehensive pediatric care for children starting from 2 weeks of age and older! Our provider is dedicated to ensuring your child receives the best possible care and treatment. We offer well-child visits, immunizations, sick and minor injury visits to keep your child healthy.

Senior Care

As we age, our healthcare needs change. We offer specialized care for seniors, including geriatric assessments and chronic disease management.

Behavioral Health

At JourneyCare Family Medicine Family, we understand that mental health is just as important as physical health ! Learn about our behavioral health services.

Laboratory and Diagnostic Imaging

As your "medical home" we are dedicated to making healthcare easier and more convenient for you by providing comprehensive healthcare services "under one roof"! We offer laboratory and diagnostic imaging in-house. Learn more about our laboratory and diagnostic imaging services.

Ready to schedule an appointment? Have questions about our services or insurance? Give us a call and our friendly staff will be happy to assist you! *Please review our cancellation and no-show policy which can be found in the "services" or "contact us" sections of this website.

We value your feedback! Please click the Google link below to rate your experience with us!

Veteran owned small business.

Here at JCFM, we are proud to be of service for our heroes who proudly served, and we thank you for your sacrifice and service!

LGBTQ+ Health Partner

JourneyCare Family Medicine is a proud advocate for healthcare diversity and inclusion, and welcomes everyone to be cared for in a warm, professional setting that is free from

bias, judgment, and prejudice.

journeycare family medicine

126 N Park drive Fayetteville, ga 30214

Office: (470) 278-2618 Fax: (678) 519-2736

Copyright © 2023 JourneyCare Family Medicine - All Rights Reserved.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.

News & Announcements

Journey Family Medicine pre-registration is open!

By Dr. Pilar Bradshaw, Owner

Published September 7, 2022

It’s been a dream of mine to create a clinic that’s similar to Eugene Pediatric Associates —a clinic for adults that’s locally owned, family-focused and provides integrated healthcare at every chapter of life—and that dream is now a reality!

I’m excited to introduce Journey Family Medicine, offering primary care for adults by applying our amazing model of integrating medical providers, behavioral health specialists and social workers to help adults achieve optimal health. Pre-registration is now open on the Journey Family Medicine website, JourneyFamilyMedicine.com . Most insurances are accepted. Opening day is Monday, October 3.

The new clinic is located right next to Eugene Pediatrics, in the same building, at 995 Willagillespie Road. Journey Family Medicine will be a welcoming spot for our older pediatric patients who want to graduate to a grown-up primary care clinic, as well as their parents and grandparents.

As owner of Journey Family Medicine, I will not be seeing patients at my new clinic. I will, however, continue to care for infants, children and young adults as a pediatrician at Eugene Pediatric Associates.

Our talented team will walk alongside you

I’ve hand-picked a talented team of clinicians for Journey Family Medicine—professionals who I trust to care for my own family and me, personally. They share my belief that each of us walk a unique path in life. It’s important that our individual healthcare journeys are in the company of clinicians who know us well and provide the personalized service that only a small, local clinic can deliver. Through all the twists and turns and ups and downs, your medical, behavioral health and social work experts at Journey Family Medicine will walk alongside you. Let me introduce them to you!

Meg Hamilton, FNP-C , and I have spent the past 20 years talking about how wonderful it would be to work together “someday.” Well, that “someday” is finally here. Meg, who I’m proud to say is my personal primary care provider, is an attentive listener, deeply compassionate, wicked smart and driven to provide the best-possible care for her patients. I have always trusted her implicitly with my own health and the health of my family members. If you or a friend or family member needs a primary care provider or is looking to make a change, I highly recommend Meg.

Lindsey Adkisson, DNP, FNP-C , was hand-picked by Meg to be her partner at Journey Family Medicine. Over the course of many months of planning this new venture, I have come to adore Lindsey and value her medical and philosophical insights. She is caring, well-rounded, highly educated and has a passion for equity in healthcare.

Tamara Hughes, LCSW , and I have known each other for years, in a variety of ways. Most recently, I have watched her work closely and successfully as a behavioral health expert at my other clinic, Thrive Behavioral Health , caring for moms with perinatal mood issues. Before that, she was a phenomenal social worker at Sacred Heart Medical Center at RiverBend. Here’s a fun fact: Tamara and her husband purchased my former house, which is proof that Eugene really is a small town! Tamara is a deep listener, kind soul and thrives on helping people. -->

Tell others, spread the word far and wide

It’s a challenging time to start a small business, so every person who chooses Journey Family Medicine is helping to make this dream a reality.

Please consider Journey Family Medicine for your primary care and tell your Eugene-Springfield family and friends. I pledge that you’ll feel loved and cared for by my amazing team throughout your healthcare journey.

Thank you for spreading the word!

– Dr. Pilar Bradshaw, Owner & Pediatrician

DISCLAIMER: No content on this website, regardless of date, should be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your primary care provider.

Website by Turell Group © 2024

- Neurology Specialists

- Pediatricians

Sheila's Weight Loss Journey

At 350 pounds, Sheila Briggs was experiencing a lot of pain and discomfort. Pre-diabetic and suffering from severe sleep apnea, she dreamed of an active life, but didn't have the energy to do much more than sit on the couch.

When you’re ready to leave pain, illness and mobility issues behind ...

Sheila was referred to MaineHealth Weight Management - Kennebunk by her endocrinologist at MaineHealth Maine Medical Center. She chose to begin her weight loss journey at oue practice because it's closer to her home in Wells and she liked the feel of a smaller program with more personalized attention.

... step out of your comfort zone and start living the life that you deserve.

From the very first meeting, Sheila felt an immediate connection to the MaineHealth Weight Management - Kennebunk team. They took the time to educate her whole family about the process - making sure everyone felt comfortable and prepared. And when they day came, her surgery was a success with zero complications.

We'll be with you for every step of your weight loss journey.

Sixteen months after her surgery, Shelia has lost 135 pounds, continues to keep the weight off, and has set a goal to lose even more weight. She’s able to do yard work, kayak, and take the family dog for a walk on Wells Beach. She is no longer pre-diabetic and no longer needs to use a CPAP machine to sleep at night. She exercises five to six times a week and meets with a trainer in Sanford once a week.

She continues to see her dietitian and attends support team meetings with her husband twice each month. She says this long-term support by the MaineHealth Weight Management - Kennebunk team has helped her stay accountable and motivated. Her husband has also been a big supporter and is thrilled with the positive impact this program has had on their family.

You’re worth it.

The best part of all? Sheila and her husband have booked their dream vacation. While in Hawaii, they plan to slide on a zip line and go horseback riding - activities Sheila could never do before, because of her weight. Sheila chose to share her story to help other people who are struggling with obesity to understand that they are valued, important, and that their life is worth living.

Want to learn more about weight loss surgery?

Join a free info session. Just complete this short form and a member of our team will contact you with more details.

Is weight loss surgery right for you?

Use our interactive decision tool to find out more.

- Visit Our Blog about Russia to know more about Russian sights, history

- Check out our Russian cities and regions guides

- Follow us on Twitter and Facebook to better understand Russia

- Info about getting Russian visa , the main airports , how to rent an apartment

- Our Expert answers your questions about Russia, some tips about sending flowers

Russian regions

- Amur oblast

- Buryat republic

- Chukotka okrug

- Jewish autonomous oblast

- Kamchatka krai

- Khabarovsk krai

- Komsomolsk-on-Amur

- Magadan oblast

- Primorye krai

- Sakha republic

- Sakhalin oblast

- Zabaikalsky krai

- Map of Russia

- All cities and regions

- Blog about Russia

- News from Russia

- How to get a visa

- Flights to Russia

- Russian hotels

- Renting apartments

- Russian currency

- FIFA World Cup 2018

- Submit an article

- Flowers to Russia

- Ask our Expert

Khabarovsk Krai, Russia

The capital city of Khabarovsk krai: Khabarovsk .

Khabarovsk Krai - Overview

Khabarovsk Krai is a federal subject of Russia located in the center of the Russian Far East, part of the Far Eastern Federal District. Khabarovsk is the capital city of the region.

The population of Khabarovsk Krai is about 1,299,000 (2022), the area - 787,633 sq. km.

Khabarovsk krai flag

Khabarovsk krai coat of arms.

Khabarovsk krai map, Russia

Khabarovsk krai latest news and posts from our blog:.

25 August, 2017 / Russian banknotes and the sights depicted on them .

1 August, 2017 / Khabarovsk - the view from above .

21 December, 2016 / Flying over diverse Russia .

21 April, 2013 / Khabarovsk - the center of the Russian Far East .

16 January, 2011 / Siberian tiger walking the highway .

More posts..

History of Khabarovsk Krai

In the Middle Ages, the territory of today’s Khabarovsk Krai was inhabited mainly by the peoples of the Tungus-Manchu language group, as well as Nivkhs. In China they were known collectively as “wild Jurchen”. In the 13th-14th centuries, the Mongol rulers of China repeatedly organized expeditions to the lower Amur.

Russians began the development of the Far East in the 17th century. In 1639, a Cossack troop headed by Ivan Moskvitin reached the coast of the Sea of Okhotsk. The first stockade town was built in the mouth of the Ulya River. Later, Vasily Danilovich Poyarkov and Yerofei Pavlovich Khabarov were the first who started joining the Amur lands to Russia. Before Russians came here, the tribes of Daurs, Evenks, Natks, Gilyaks and others lived in this area (only about 30 thousand people).

The area was quickly populated by Russian settlers; new stockade towns were founded. But the process was interrupted due to a conflict with the Qing Dynasty. From the 1680s, Manchus started to fight against the Russian state.

More Historical Facts…

Russia could not move significant military forces to the Amur region and had to sign the Treaty of Nerchinsk (1689). According to it, Russians had to leave the left bank of the Amur River but managed to uphold its rights for the area behind Lake Baikal and the Sea of Okhotsk coast.

In the 18th century, Okhotsk became the main Pacific port of the Russian Empire. Development of the northern coast of the Pacific, exploration of the Kuril Islands and Sakhalin prepared the basis for the return of the Amur region.

In 1847, Nikolai Nikolayevich Muravyov was appointed a governor-general of Eastern Siberia. He did his best to return the Amur area to the Russian Empire. The number of Russians in the region began to grow. In 1858, the town of Khabarovsk was founded.

As a result of the weakening of China during the Opium Wars, two agreements were signed - the Aigun Treaty in 1858 and the Beijing Treaty in 1860. The Russian-Chinese border was established on the Amur and Ussuri rivers.

In 1884, Zabaikalskaya, Amurskaya and Primorskaya regions were united into Priamurskoye region with the center in Khabarovsk. Until the late 19th century, the Amur area was settled slowly. The situation changed in the early 20th century. In 1900, the Trans-Baikal Railway was opened, in 1902 - the Chinese Eastern Railway.

As a result, the number of settlers grew rapidly. In 1900-1913, about 300,000 peasants from other regions of the Russian Empire came to the Amur area. There were three towns (Khabarovsk, Nikolayevsk-on-Amur and Okhotsk) on the territory, which makes Khabarovsk krai today. By 1915, there were more than six thousand settlements with a total population of 316,300 people in Primorskaya oblast.

The Civil War lead to a great number of deaths and economic collapse in Russia. The restoration of pre-war level of economy was achieved by 1926. New cities were built in the region - Komsomolsk-on-Amur, Birobidzhan. October 20, 1938, Dalnevostochny region was divided into Khabarovsky and Primorsky regions.

In 1947-1948, Sakhalin and Amur regions were separated from Dalnevostochny region. In 1953, Magadan region was formed and separated from Dalnevostochny region. In 1956, Kamchatka region became independent too. In 1991, the Jewish autonomous region was separated from Dalnevostochny region.

Nature of Khabarovsk Krai

Khabarovsk Krai scenery

Author: Alexander Semyonov

Khabarovsk Krai landscape

Author: Alexander Makharov

Lake in Khabarovsk Krai

Author: Ezerskiy Feliks

Khabarovsk Krai - Features

Khabarovsk Krai is one of the largest administrative-territorial units of the Russian Federation. The territory of the region stretches for about 1,800 kilometers from north to south, and for 125-750 km from west to east. The distance from Khabarovsk to Moscow is 8,533 km by rail, 8,385 by roads and 6,075 km by air.

Part of the southern boundary of the Khabarovsk region is the state border of Russia with China. The province is washed by the Sea of Okhotsk and the Sea of Japan. The coastline extension is 3,390 km, including islands, the largest of them are Shantarsky Islands. The highest point is Berill Mountain (2,933 meters).

The climate of the region changes from north to south. Winters are long and snowy. The average temperature in January is in the range of minus 22-40 degrees Celsius, on the coast - minus 18-24 degrees Celsius. Summers are hot and humid. The average temperature in July is about plus 15-20 degrees Celsius.

In general, Khabarovsk Krai is one of the most sparsely populated regions of Russia, which is due, firstly, the general economic decline of the post-Soviet time, and secondly - the severity of the local climate, comparable with the regions of the Far North.

The largest cities and towns are Khabarovsk (613,500), Komsomolsk-on-Amur (239,400) Amursk (38,200), Sovetskaya Gavan (22,900), Nikolaevsk-on-Amur (17,400), Bikin (15,900).

Khabarovsk Krai - Economy and Transport

The main branches of the local economy are mechanical engineering and metalworking, ferrous metallurgy, mining, fishing, food, light and timber industries. The mineral resources of the region include gold, tin, aluminum, iron, coal and lignite, graphite.

The main highways of Khabarovsk Krai are M60 “Ussuri” (Khabarovsk - Ussuriysk - Vladivostok) and M58 “Amur” (Chita - Never - Svobodny - Arkhara - Birobidzhan - Khabarovsk). The railway station “Khabarovsk-2” is a large railway hub. The directions are as follows: to the south (to Vladivostok and Port Vostochny), to the west (to Moscow) and to the north (to Komsomolsk-on-Amur).

The river port in Khabarovsk is the largest on the Amur River. The other river ports of the region are located in Komsomolsk and Nikolayevsk. The sea ports of the region are Okhotsk, Ayan, Nikolayevsk-on-Amur, Vanino, Sovetskaya Gavan.

Tourism in Khabarovsk Krai

The rich natural potential of the region provides endless opportunities for the development of ecological tourism. You can see reindeer, brown and Himalayan bears, bighorn sheep and even the Siberian tigers on the territory of Khabarovsk krai.

The Amur River is the main attraction of the region. Most of natural, cultural and historical tourist sites are concentrated in the valley of this river.

Shantarsky Islands, one of the most beautiful and unique places of unspoiled nature, are another natural attraction of this region. The inaccessibility of the islands allowed to preserve pristine nature. Shantarsky Islands are a habitat of whales, seals, killer whales. It is a great place for fishing.

If you prefer ethnographic tourism, you may be interested in cave paintings located near the Nanai village of Sikachi-Alyan and Lake Bolon, which is a large bird sanctuary. In the past, there were a Buddhist temple and ancient settlements in the vicinity of the lake.

Lovers of adventure tourism may be interested in rafting, fishing tours, caving and winter recreation.

The best time for tourism in Khabarovsk krai: “late spring - early summer”, “end of summer - early fall.”

The largest international airport in the region is located in Khabarovsk. The flights to Moscow, Vladivostok, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, Novosibirsk, Yakutsk, Krasnoyarsk, Irkutsk, Bangkok, Seoul, Harbin are available.

Khabarovsk krai of Russia photos

Pictures of khabarovsk krai.

Author: Sergey Kotelnikov

Author: Evgeniy Lopatin

Forest in Khabarovsk Krai

Winter in Khabarovsk Krai

Author: Volman Michail

The questions of our visitors

The comments of our visitors.

- Currently 2.88/5

Rating: 2.9 /5 (161 votes cast)

Sponsored Links:

Browse Econ Literature

- Working papers

- Software components

- Book chapters

- JEL classification

More features

- Subscribe to new research

RePEc Biblio

Author registration.

- Economics Virtual Seminar Calendar NEW!

The Socio-Economic Profile of the Khabarovsky Krai – 2020

- Author & abstract

- Related works & more

Corrections

- Ruslan Gulidov

(Federal Autonomous Scientific Institution «Eastern State Planning Center»)

Suggested Citation

Download full text from publisher.

Follow serials, authors, keywords & more

Public profiles for Economics researchers

Various research rankings in Economics

RePEc Genealogy

Who was a student of whom, using RePEc

Curated articles & papers on economics topics

Upload your paper to be listed on RePEc and IDEAS

New papers by email

Subscribe to new additions to RePEc

EconAcademics

Blog aggregator for economics research

Cases of plagiarism in Economics

About RePEc

Initiative for open bibliographies in Economics

News about RePEc

Questions about IDEAS and RePEc

RePEc volunteers

Participating archives

Publishers indexing in RePEc

Privacy statement

Found an error or omission?

Opportunities to help RePEc

Get papers listed

Have your research listed on RePEc

Open a RePEc archive

Have your institution's/publisher's output listed on RePEc

Get RePEc data

Use data assembled by RePEc

The Potential of the Khabarovsk Krai, Jewish Autonomous Region and the Amur Oblast for Fluorite Mineralization

- Published: 02 August 2023

- Volume 17 , pages 364–376, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- A. A. Cherepanov 1 &

- N. V. Berdnikov 1

30 Accesses

Explore all metrics

The available data on the fluorite potential of the Khabarovsk krai, the Jewish Autonomous Region and Amur oblast have been synthesized. Fluorite deposits and occurrences were ascribed to the rare-earth–fluorite, beryllium–fluorite, fluorite–tin-ore, base-metal–fluorite, and fluorite mineralization types. Fluorite also occurs in the ore and phosphorite deposits of the fluorite-bearing mineralization type. The features of their localization in different tectono-stratigraphic areas of the region are shown. Fluorite-bearing districts were identified and their economic potential was assessed. Most promising fluorite occurrences are located along the periphery of the Siberian platform and in the southern part of the Bureya massif. Inferred fluorite resources were calculated and the prospects for their industrial development were estimated.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price excludes VAT (USA) Tax calculation will be finalised during checkout.

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Fluorite Deposits

Geochemical characteristics of the qahr-abad fluorite deposit, southeast of saqqez, western iran.

Mineralogical-Technological Characteristics of the South-Western Lupikko Fluorite Occurrences, Republic of Karelia

N. V. Gorelikova, B. I. Semenyak, P. G. Korostelev, V. I. Taskaev, F. V. Balashov and V. A. Rassulov, “Rare earth minerals in the rare-metal greisens of the Verkhnee Deposit in the Khingan–Olonoisky District of the Amur Region, Russia,” Russ. J. Pac. Geol. 16 (6) 608–623 (2022).

V. A. Gur’yanov, Geology and Metallogeny of the Ulkan District (Aldan–Stanovoy Shield) (Dal’nauka, Vladivostok, 2007) [in Russian].

Google Scholar

I. I. Egorov, I. P. Ovchinnikov, and K. A. Nikiforov, “New type of fluorite ores,” Razved. Okhr. Nedr, No. 9, 13–18 (1966).

A. A. Ivanova, “Prediction of fluorite mineralization based on formation classification,” Razved. Okhr. Nedr, No. 7, 12–18 (1977).

A. A. Ivanova, Yu. I. Mikhailova, and S. A. Novolinskaya, “Fluorite,” Criteria for Forecasting Assessment for Solid Minerals (Nedra, Leningrad, 1986), pp. 610–628.

A. V. Koplus, “Fluorspar,” Methodical Guide on the Assessment of Predictin Resources of Solid Minerals (Moscow, 1989), Vol. 4, pp. 119–151 [in Russian].

A. V. Koplus, “Mineral-Raw Base of the World and Russia: state, development, and prospects. Fluorspar,” Mineral Raw Material. Geological-Economic Series (VIMS, Moscow, 2000), No. 5.

A. V. Koplus and A. G. Romanov, “State, problems, and prospects of mineral-raw base of fluorspar in Russia,” Razved. Okhr. Nedr, No. 6, 36–42 (2012).

P. G. Korostelev, B. I. Semenyak, S. B. Demashov, et al., “Some compositional features of ores of the Khingan–Olonoy area,” Ore Deposits of Continental Margin (Dal’nauka, Moscow, 2000), Vol. 1, pp. 202–225 [in Russian].

I. I. Kupriyanova and E. P. Shpanov, Beryllium Deposits of Russia (GEOS, Moscow, 2011) [in Russian].

M. V. Martynyuk, A. F. Vas’kin, A. S. Vol’skii, et al., Geological Map of the Khabarovsk Krai and Amur Region. 1 : 500 000: Explanatory Note (Khabarovsk, 1988) [in Russian].

Methodical Guidebook on Assessment of Prediction Resources of Solid Minerals. Fluorspar , (Kazan’, 1986), Vyp. A, pp. 134–151 [in Russian].

M. I. Novikova and N. N. Zabolotnaya, “Beryllium-bearing feldspathic metasomatites of the Mesozoic activation zones,” Sov. Geologiya, No. 12, 92–100 (1988).

D. O. Ontoev, Geology of Complex Rare-Earth Deposits (Nedra, Moscow, 1984) [in Russian].

D. O. Ontoev, “Complex rare-earth deposits as new sources of barium, strontium, and fluorine,” Sov. Geologiya, No. 4, 33–42 (1988).

M. D. Ryazantseva, “Fluorite deposits of the Khanka median massif,” Geology and Genesis of Fluorite Deposits (Vladivostok, 1986), pp. 98–107 [in Russian].

L. V. Tausov, Geochemical Types and Ore Potential of Granitoids (Nauka, Moscow, 1977) [in Russian].

A. A. Frolov and Yu. A. Bogdasarov, “Carbonatites as a new genetic type of fluorite deposits,” Razved. Okhr. Nedr, No. 7, 6–8 (1968).

A. A. Cherepanov, N. K. Krutov, M. D. Ryazantseva, and G. G. Arkhipov, “Fluorite mineralization of the Far East and USSE Norteast, Tr. Assots. Dal’nedra (Khabarovsk, 1991), Vol. 1, pp. 170–189.

A. A. Cherepanov and N. V. Berdnikov, Stratiform Fluorite Mineralization in the Surrounding of the Siberian Platform and Russian East (Khabarovsk, 2022) [in Russian].

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Kosygin Institute of Tectonics and Geophysics, Far Eastern Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, 680000, Khabarovsk, Russia

A. A. Cherepanov & N. V. Berdnikov

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to N. V. Berdnikov .

Ethics declarations

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Recommended for publishing by A.P. Sorokin

Translated by M. Bogina

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cherepanov, A.A., Berdnikov, N.V. The Potential of the Khabarovsk Krai, Jewish Autonomous Region and the Amur Oblast for Fluorite Mineralization. Russ. J. of Pac. Geol. 17 , 364–376 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1819714023040024

Download citation

Received : 12 January 2023

Revised : 10 March 2023

Accepted : 24 March 2023

Published : 02 August 2023

Issue Date : August 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1134/S1819714023040024

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- metallogenic provinces

- fluorite-bearing mineralization types

- fluorite deposits

- Amur oblast

- Jewish Autonomous Region

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Places - Siberia and the Russian Far East

Russian Far East

The Russian Far East is a region in eastern Russia that includes the territories that run along the Pacific coast and the Amur River, the Kamchatka Peninsula, Sakhalin island and the Kuril Islands. It is a cold, inhospitable and sparsely populated area with stunning scenery, rich fisheries, virgin forest, remote towns, Siberian tigers and Aumur leopards. Sometimes the Russian Far East is regarded as part of Siberia.

Rachel Dickinson wrote in The Atlantic: Russia’s Far Eastern Federal District is huge — 2.4 million square miles, roughly twice the size of India — and takes up one-third of the country, but only 6.7 million people populate that vast space. (The district’s biggest city is Vladivostok — best known for being the last stop on the Trans-Siberian Railroad and home to the Russian Pacific fleet.) Provideniya was once a thriving military town with a population as high as 10,000; today the population is about 2,000. Most of the ethnic Russians have left, ceding the city to the region’s indigenous people. Now the government is struggling to stem the tide of people leaving the desolate Far East. [Source: Rachel Dickinson, The Atlantic, July/August 2009]

The entire Russian Pacific coastline extends for almost 16,000 kilometers (10,000 miles). The formal dividing line between Siberia and the Far East are the borders of the Khabarovsk territory and Magadan region, which extends between 160 kilometers (100 miles) to 1,600 kilometers (1,000 miles) inland from the Russia's east coast. Siberia, the Russian Far East and Kamchatka were largely covered by glaciers during the last Ice Age, which ended about 10,000 years ago. In the Soviet era, the Far East had its share of gulags and labor camps, Maksim Gorky called it " land of chains and ice." Since the break up of the Soviet Union, its people have largely been forgotten. The whole region would probably be forgotten if it weren't so rich in resources.

The Far East only has 6.7 million people and its population is falling. There used to be around 8 million people there. Eighty percent of the people live in the cities but have a strong ties to the land: hunting, fishing or picking berries and mushrooms whenever they get the chance. Some places only exist because the government subsidizes them, providing the people with shipped-in food and cheap energy for heat. In the early 2000s, the government has decided it has spent too much supporting these people and told them they have to move. In some places the people refused to move and the government cut off their water and heat and they still stayed. In recent years thing have stabilized somewhat as more money has flowed in from oil, natural gas, minerals, fishing and timber.

What the Russian Far East lacks in historical sites, old cities and museums — compared to the European parts of Russia and even Siberia — it makes up for with a wide variety of beautiful scenery and adventures. The Amur Rive boast sturgeons the size of whales. In the Primorskiy territory you can find rocky islands, steep cliffs, Siberian tigers and Amur leopards. There are isolated beaches on rivers and the see. If you like taiga, there lots of that along with wild mountains and many places to go hiking, fishing, hunting and camping. On Kamchatka there are dozens of very active 's volcanoes. Further north are some of the best places in the world to see walruses, polar bears and whales. Khabarovsk and Vladivostok are two major cities that define the eastern end of the Trans-Siberian Railway and have plenty of urban activities.

The Far Eastern Federal District is the largest of the eight federal districts of Russia but the least populated. The 11 federal subjects are: 1) Amur Oblast: 361,900 square kilometers, 830,103 people, capital: Blagoveshchensk 2) Republic of Buryatia: 351,300 square kilometers,, 971,021 people, capital: Ulan-Ude 3) Jewish Autonomous Oblast: 36,300 square kilometers, 176,558 people, capital: Birobidzhan 4) Zabaykalsky Krai: 431,900 square kilometers, 1,107,107 people, capital: Chita 5) Kamchatka Krai: 464,300 square kilometers, 322,079 people, capital: Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky 6) Magadan Oblast: 462,500 square kilometers, 156,996 people, capital: Magadan 7) Primorsky Krai: 164,700 square kilometers, 1,956,497 people, capital: Vladivostok 8) Sakha Republic: 3,083,500 square kilometers, 958,528, people capital: Yakutsk 9) Sakhalin Oblast: 87,100 square kilometers, 497,973 people, capital: Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk 10) Khabarovsk Krai: 787,600 square kilometers, 1,343,869 people, capital: Khabarovsk 11) Chukotka Autonomous Okrug: 721,500 square kilometers, 50,526 people, capital: Anadyr

Traveling in the Far East is troublesome. There are few roads, and they are in poor conditions. Many places can’t be reached by road anyway. Rivers are frozen much of the year. Helicopters can cost as much as US$500 an hour to rent. Corruption is rampant and it seems like everyone wants a cut. Even if paperwork is in order customs officials, police an other authorities demand, sometimes, huge outrageous "fees."

Economics of the Far East

The Far East is rich in gold, diamonds, oil, natural gas, minerals, timber and fish. It accounts for more than 60 percent of Russia's total sea harvest and fishing is the region’s leading industry, providing jobs for more than 150,000 people. People in the Far East should be rich from the wealth generated from fishing, timber and minerals but that is not necessarily the case. In the case of timber, in the early 2000s, local communities were supposed to get 30 percent of the profits but in reality Moscow took 80 percent and local officials took the rest.

In the early 2000s, gas and oil companies could not pay their workers and utility companies couldn’t pay the oil and gas companies and as a result electricity was only on for a few hours a day. Workers were among the last to receive their wages, factories were cannibalized of scrap metal and parts, students studied in sub-freezing classrooms, and people died at early ages. Those that could afford it moved away.

Many foreign companies were equally frustrated. The U.S. wood product giant Weyerhaueser, Korea's Hyundai conglomerate and Australian mining companies arrived in east Russia with high hopes but after some time there either packed up and left or scaled down their staff down to a skeletal crew.

Ussuri River

The Ussuri River forms the border between Russia and China in southern Khabarovsk Krai and . Primorsky Karia. A right tributary of the Amur, it is 897 kilometers long, with a basin area of more than 193,000 square kilometers. The Ussuri River originates in the spurs of the central Sikhote-Alin. Once it descends into it the valley, the river becomes flat and gentle but has a steep rocky coast. In many area there are meandering channels.

Among the tributaries of the Ussuri are: 1) the upper river: Izvilinka, Sokolovka, Matveyevka and Pavlivka. 2) the left tributaries: Arsen'evka, Muling, Naoli River and Songacha River; 3) and the right tributaries: Pavlovka, Zhuravlovka, Big Ussurka, Bikin and Khor.

In Khabarovsk Krai, near the village of Kazakevichevo, Ussuri River flows into the shallow Kazakevichevo channel and after that the confluence of the Ussuri is called the Amur channel. The Amur channel empties into the Amur River in the center of the city of Khabarovsk. The Ussuri is a full-flowing river from May to August. In the summer and when the ice breaks there are frequent floods. Ice on the Ussuri breaks up in April and forms in November. The water is used for water supply. Above Lesozavodsk the river is navigable. Previously it was widely used for timber floating.

The Ussuri River is good for fishing and rich in fish. Gudgeon, crucian carp, common carp, trout, burbot, pike, catfish, flax and grayling are all caught as are Kaluga sturgeon, which can reach a huge size (eight meters recorded in the Amur River). The river is a spawning ground for salmon and chum salmon. In the waters of the Ussuri fish mountain rivers are found near the bottom fish. Mountain fish comes to the Ussuri in the spring to spawn.

Ussuri Taiga and Dersu Uzala

The Ussuri taiga is a forest different from the normal Russian taiga. Located between the Ussuri and Amur Rivers in the Far East and dominated by the Sikhot Alim Mountains, it is a monsoon forest filled with plants and animals found nowhere else in Siberia or Russia and instead are similar to those found in China, Korea and even the Himalayas. In the forest there is s lush undergrowth, with lianas and ferns. Wildlife include Siberian tigers, Asian black bears, Amur leopards and even tree frogs. The Siberian Tiger Project is located here. The 1970 Akira Kurosawa Oscar-winning film “Dersu Uzala,” and the book it was based on, about a Tungus trapper, was set here.

Ian Frazier wrote in The New Yorker: ““Dersu Uzala,” the memoir and narrative of exploration by Vladimir K. Arsenyev, begins in 1902, when Arsenyev is a young Army officer assigned the job of exploring and mapping the almost unknown regions east and northeast of Vladivostok, including Lake Khanka and the upper watershed of the Ussuri River. The name for the whole area is the Primorskii Krai—the By-the-Sea Region. It and much of the Khabarovskii Krai, just to the north of it, consist of a unique kind of Pacific forest in which tall hardwoods hung with vines grow beside conifers almost equally high, and the lushness of the foliage, especially along the watercourses, often becomes quite jungly. [Source: Ian Frazier, The New Yorker, August 10 and 17, 2009, Frazier is author of “Travels in Siberia” (2010) ]

“In Arsenyev’s time, this jungle-taiga was full of wildlife, with species ranging from the flying squirrel and the wild boar to the Siberian tiger. Back then (and even recently) tigers could also be seen on the outskirts of Vladivostok, where they sometimes made forays to kill and carry off dogs. Arsenyev describes how tigers in the forest sometimes bellowed like red deer to attract the deer during mating season; the tiger’s imitation betrayed itself only at the end of the bellow, when it trailed off into a purr.

“The humans one was likely to meet in this nearly trackless forest were Chinese medicine hunters, bandits, inhabitants of little Korean settlements, and hunter-trappers of wild game. Dersu Uzala, a trapper whom Arsenyev and his men come upon early in their 1902 journey, is a Siberian native of the Nanai tribe whose wife and children have died of smallpox and who now is alone. After their meeting, Dersu becomes the party’s guide. The book is about Arsenyev’s adventures with Dersu on this journey and others, their friendship, and Dersu’s decline and end.

“In the nineteen-seventies, a Soviet film studio produced a movie of “Dersu Uzala,” directed by Akira Kurosawa. It won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film of 1975. The movie is long and slow-paced, like a passage through the forest, and wonderfully evokes the Primorskii country. I own a cassette of the movie and in my many viewings of it even picked up some useful fractured Russian from the distinctive way Dersu talks.

Udegeh: People Who Live with Siberian Tigers

The Udegeh live around the Sikhotealin Mountains in the Far East, also home to many Siberian tigers, and traditionally survived by hunting in the forest. Their ancestors were farmers and members of the Zhurdzhen empire, which ruled parts of what is now China, Mongolia and Russia. In the 13th century, Zhurdzhen was defeated by Genghis Khan and the Mongols and survived in scattered communities in the forest, where they became nomadic hunters to survive and formed their own language and culture, called Udegeh. There are only about 2,000 Udegeh left. The largest group lives in a village called Krasnyr, about 175 miles southeast of Khabarovsk.

The Udegeh live in wooden houses that often have painted gables with images of bears, dogs, devils and pagan goddesses. Their villages are surrounded by forests, and in the winter deep snow. They primarily live on animals they hunt such as sable, mink, squirrel, deer and boar. They often earn what little money they have by collecting wild ginseng in the forest or selling furs.

About 80 Siberian tigers live in the Udegeh hunting grounds. The Udegeh worship tigers, which are considered sinful to kill. One Udegeh hunter told the Washington Post, "The tiger and the Udegeh people are the same."

In the 1920s, the Udegeh were organized into hunting cooperatives by the Soviets. They sold furs to the Soviets and were able to keep their culture alive even though the Communists frowned upon their pagan beliefs and shaman practices. Today most young Udegeh wear Russian clothes and few of them speak the old language. Intermarriage is common and there are few pure blood Udegeh left. In the early 1990s, the Udegeh were involved in a dispute with the South Korean conglomerate Hyundai, who wanted to log the Udegeh's hunting ground.

See Separate Article PEOPLE OF THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST factsanddetails.com

Ussuriisk (kilometer 9177 on the Trans-Siberian, an hour and a half drive from Vladivostok) contains a "Chinese Bazaar" that is more like a separate town. The market operates all night and approximately 2,000 Chinese traders live semi-permanently in metal freight containers near their stalls.

The Museum of History and Local Lore and the famous 800-year-old stone turtle will introduce you to the history of this city. At the end of summer, tourists come to see the city's blooming lotuses. In the winter, you can enjoy a swim in an outdoor pool, surrounded by snowy fir trees. There is a historical park of everyday life and customs of the Russian people called “Emerald Valley” located five kilometers away from the city . Various events are held here, including the celebration of Kupala Night, jousting tournaments, Christmas and Maslenitsa festivities.

Ussuriisk is located near the border with China and North Korea and stands at the confluence of the Komarovka, Rakovka and Razdolnaya. The city was founded in 1866 by Russians from Voronezh and Astrakhan province in East Russia and the Capian Sea area. The town began to grow when the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway began in the area.

Places Where the Siberian Tigers Live

Siberian tigers today are confined primarily to the Ussuri Taiga, a forest different from the normal Russian taiga. Located between the Ussuri and Amur Rivers in the Far East and dominated by the Sikhot Alim Mountains, it is a monsoon forest filled with plants and animals found nowhere else in Siberia or Russia and instead are similar to those found in China, Korea and even the Himalayas. In the forest there is s lush undergrowth, with lianas and ferns. Wildlife include Siberian tigers, Asian black bears, Amur leopards and even tree frogs. The Siberian Tiger Project is located here. The 1970 Akira Kurosawa film Dersu Uzala, about a Tungus trapper, was set here.

Sikhot Alin Reserve and Kedrovaya Pad Reserve within the Ussuri Taiga are the last homes of the Siberian tiger. The largest wildlife sanctuaries in the Far East, they embrace 1,350 square miles of forested mountains, coastline and clear rivers. Other animals found in Sikhot Alin reserve and Kedrovaya Pad reserve include brown bears, Amur leopard (of which only 20 to 30 remain), the Manchurian deer, roe deer, goral (a rare mountain goat), Asian black bears, salmon, lynx, wolf and squirrels with tassels on their ears, azure winged magpies and the emerald-colored papilio bianor maackii butterfly. Over 350 different species of bird have been sen here.

Dunishenko and Kulikov wrote: “In the 19th century, aside from the Sikhote-Alin and Malyi Khingan portions of Russia, tigers were found in southeastern Transcaucasia, in the Balkhash basin, in Iran, China and Korea. Now the Amur tiger is found only in Russia’s Primorskii and southern Khabarovskii Krais. This is all that remains of an enormous tiger population that formerly numbered in the thousands and that lived mostly in China. In the spring of 1998, one of the authors of this booklet took part in an international scientific study investigating the best tiger habitat remaining in the Chinese province of Jilin. We found three to five tigers there, mostly along the Russian border. Our general impression is that there are no more than twenty or thirty Amur tigers in all of China. [Source: “The Amur Tiger” by Yury Dunishenko and Alexander Kulikov, The Wildlife Foundation, 1999 ~~]

The general area where Siberian tigers lives is called the Primorskii or Primorye, a region of the southeast Russian Far East that embraces Vladivistok. John Vaillant wrote in “The Tiger: A True Story of Vengeance and Survival”: “Primorye, which is also known as the Maritime Territory, is about the size of Washington state. Tucked into the southeast corner of Russia by the Sea of Japan, it is a thickly forested and mountainous region that combines the backwoods claustrophobia of Appalachia with the frontier roughness of the Yukon. Industry here is of the crudest kind: logging, mining, fishing, and hunting, all of which are complicated by poor wages, corrupt officials, thriving black markets — and some of the world's largest cats.” [Source: John Vaillant. “The Tiger: A True Story of Vengeance and Survival” (Knopf, 2010)]

Nezhino (100 kilometers north of Vladivostok, 20 kilometers east of the Chinese border) is used as a base for people who track Siberian tigers. They are particularly easy to track in the winter, if you can initially locate some tracks, when they leave big paw prints in the snow. Tigers tracking tours began being offered in 2005.

See Separate Articles: SIBERIAN TIGERS factsanddetails.com ; PLACES WHERE THE SIBERIAN TIGERS LIVE factsanddetails.com ; HUMANS, SCIENTISTS, CENSUSES AND SIBERIAN TIGERS factsanddetails.com ; ENDANGERED SIBERIAN TIGERS factsanddetails.com ; SIBERIAN TIGERS CONSERVATION factsanddetails.com ; SIBERIAN TIGER ATTACKS factsanddetails.com .

Ussuri Nature Reserve and Lake Khanka

Ussuri Nature Reserve (100 kilometers north of Vladivostok) is specially protected natural area located in the southern Sikhote-Alina range, It is rich in virgin liana conifer-deciduous forests, which have been cut down in other parts of the Russian Far East and the neighboring countries. The reserve is named after Academician Vladimir L. Komarov, a Russian botanist who studied the flora of East Asia. He first gave a description of the area, visiting her in 1913.

The reserve was created in 1932 and since then has significantly increased its area, which now amounts to 4,040 square kilometers. The reserve embraces lowlands and mountains and foot hools formed by the the southern spurs of the Sikhote-Alin (Przewalski Mountains). The average elevation is 300-400 meters above sea level. The highest peaks are 650-700 meters high. There are also mountain rivers in canyon-like narrow valleys and small waterfalls. Summers are warm and humid. Winters are moderately severe with little snow. The coldest month is January (average temperature of -17.9 degrees C). The warmest month is August 19.7 degrees).

The flora of the reserve is composed almost entirely of forest species, mainly those found in cedar-broadleaf forests, which are are characterized by high species diversity and different from ecosystems found in Russia and elsewhere in the former U.S.S.R. A typical plot of pine forests, contains trees, shrubs and vines from 50-60 species. Among the many rare plants and ginseng, hard juniper, mountain peony and Chinese Prinsep

The fauna of the reserve is typical of coniferous and deciduous forests: wild boar, red deer, musk deer, and black bear. Among the birds are common warblers, blue nightingale, nuthatch and grouse. The reserve is home to the largest beetle fauna of Russia: It is interesting that several attempts to "diversify" the species composition of fauna — through the the introduction of sika deer and Barguzin sable — did not work as hoped. Most of the reserve is off limits to visitors. Among the places that one can visit are the rehabilitation center for the education of orphaned bear cubs. Reserve staff tell the story of each bear and describe it character and habits. There is also a nature trail and small museum.

Lake Khanka (200 kilometers from Vladivostok) has an average depth of 4.5 meters and is home to more than 300 species of bird and 75 species of fish. Trips to the lake includes stops at the villages of Kamen-Rybolov and Troitskoye on the west side of the lake and a trip to Gaivoron, near the town of Spassk-Dalniy, where there is a 10,000 square meter open air cage with a family of Siberian tigers. The cage is made of a transparent metallic net. The enclose incorporates the surrounding forest so you can see the tiger is a pretty close facsimile to how they lin nature.

Biodiversity of the Ussuriskii Taiga Forest

Siberian tigers inhabits the Ussuriskii taiga forest, a coniferous broadleaf forest that specifically favors the so-called Manchurian forest type. The Manchurian forests are located in riparian areas and are particularly high in biodiversity. John Goodrich of NPR wrote: “The most bio-diverse region in all of Russia lies on a chunk of land sandwiched between China and the Pacific Ocean. There, in Russia's Far East, subarctic animals — such as caribou and wolves — mingle with tigers and other species of the subtropics. It was very nearly a perfect habitat for the tigers — until humans showed up. The tigers that populate this region are commonly referred to as Siberian tigers, but they are more accurately known as the Amur tiger. "Imagine a creature that has the agility and appetite of the cat and the mass of an industrial refrigerator," Vaillant tells NPR's Linda Wertheimer. "The Amur tiger can weigh over 500 pounds and can be more than 10 feet long nose to tail." [Source: John Goodrich, NPR, September 14, 2010]

Dunishenko and Kulikov wrote: "The range of biodiversity experienced by the early explorers in the Ussuriskii taiga forest is hard to imagine. Read Vladimir Arsenev and Nikolai Przhevalskii and you’ll realize that the region’s present-day richness is but a sad remnant of what was once found here. The fact is, that not all that long ago there was a lot more to be found in our taiga. Old-timers can still vividly recall the herds of deer, numbering in the hundreds, that migrated the lightly snow covered regions of China, the incessant moan in the taiga when red Manchurian deer were mating, the endless waves of birds, the rivers boiling with salmon. [Source: “The Amur Tiger” by Yury Dunishenko and Alexander Kulikov, The Wildlife Foundation, 1999 ~~]

"And my lord, how many wild boar there used to be in the taiga! All winter long, the southern exposures of oak-covered hills were dug up by droves of wild pigs. Snow under the crowns of Korean pine forests was trampled to ground level as wild boar gathered pine cones throughout the winter. A symphony of squeal and moan! Mud caked wild boar racing around the taiga, rattling around in coats of frozen icycles after taking mud baths to cool passion-heated bodies. Horrible, blood caked wounds, chattering tusks, snorting, bear-like grunting, squawky squeaking, oh the life of a piglet.~~

"This was an earlier image of the Ussuriskii taiga. Just 30 years ago a professional hunter could take 60 to 80 wild boar in a season! There was more than enough game for the tiger out there among the riotous forest “swine.” Tigers strolled lazily, baron-like and important. They avoided the thick forests: why waste energy with all the boar trails around — you could roll along them sideways! It was only later on that the tigers took to following human trails.~~

"How many tigers there used to be in the wild can only be conjectured. Southern Khabarovskii Krai is a natural edge of their habitat; at one point in history there was a substantial tiger population that spilled over into surrounding regions. The tiger’s range coincided, for the most part, with Korean pine and wild boar distribution, and the number of tigers in the Russian Far East in the last century was at least one thousand. Tigers densely settled the Malyi Khingan and the Korean pine, broad leaf deciduous forests typical of southern Amurskaya Oblast. Lone animals wandered out as far as Lake Baikal and Yakutiya."~~

Sikhote Alin Reserve

Sikhote Alin Reserve (400 kilometers northeast of Vladivostok) and Kedrovaya Pad Reserve are the last homes of the Amur (Siberian) tiger. The largest wildlife sanctuary in the Far East. It embraces 3,500square kilometers (1,350 square miles) of forested mountains, coastline and clear rivers. Other animals found in reserves include brown bears, Amur leopard (of which only 40 to 50 remain), the Manchurian deer, roe deer, goral (a rare mountain goat), Asian black bears, salmon, lynx, wolf and squirrels with tassels on their ears, azure winged magpies and the emerald-colored papilio bianor maackii butterfly. Over 350 different species of bird have been seen here.

Central Sikhote-Alin was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2001. According to UNESCO: “The Sikhote-Alin mountain range contains one of the richest and most unusual temperate forests of the world. In this mixed zone between taiga and subtropics, southern species such as the tiger and Himalayan bear cohabit with northern species such as the brown bear and lynx. After its extension in 2018, the property includes the Bikin River Valley, located about 100 kilometers to the north of the existing site. It encompasses the South-Okhotsk dark coniferous forests and the East-Asian coniferous broadleaf forests. The fauna includes species of the taiga alongside southern Manchurian species. It includes notable mammals such as the Amur Tiger, Siberian Musk Deer, Wolverine and Sable. [Source: UNESCO]

Founded in 1935, Sikhote-Alin Nature Reserve covers an area of 3,902 square kilometers, plus and 2.9 square kilometers offshore. The reserve is located in the northern part of Primorsky Krai and includes the eastern slope of the Sikhote-Alin mountain range from its watershed to the coast (including one kilometer of shoreline), as well as a part of the western slope of the mountain range. The maximum elevation in the reserve is 1598 meters.

The reserve was originally established to protect sable populations that were on the verge of extinction. V.K. Arsenyev was one of the initiators of the reserve. K.G. Abramov and Y.A. Salmin substantiated the need to create the reserve. In our age when there are fewer and fewer untouched corners of nature on the globe, The profusion and diversity of the reserve’s ecosystems are attributable to the fact that the park includes different slopes of the Sikhote-Alin, range which differ in natural conditions and elevation. Availability of direct access to the sea is another important factor.

The reserve includes parts of three landscape areas: 1) Terney (cedar broad-leaved forests), 2) Samargino-Dalnegorsky (in the subzone of broad-leaved and coniferous forests) and 3) Mid-Sikhote-Alin (fir and spruce forests) in a boreal coniferous forest subzone. The flora and fauna in the reserve are strongly influenced by the presence of the Sea of Okhotsk: dark boreal coniferous forests are more strongly represented here than in other reserve in Primorye Krai. At the same time, conditions exist for the development of the Manchuria-like ecosystems. A distinctive feature of the flora and fauna in the reserve is the combination of heat-loving and cold-loving natural species. For its long-term research program and achievements in the conservation of the Amur tiger, the reserve was awarded with a CATS international certificate in 2015, becoming the only reserve in Russia (and the second in the world) to receive such recognition.

Traveling by Road Around Sikhote Alin Reserve

Ian Frazier wrote in The New Yorker: ““Rather than continue south, directly to Vladivostok, our ultimate destination, we had decided to turn east again, cross the Sikhote-Alin Mountains, and arrive at the Pacific (technically the Sea of Japan) in a less inhabited place on the mountains’ other side. The Sikhote-Alins, once we were among them, seemed more like hills, and not very forbidding, but the depth and silence of their forest made up for that. Arsenyev had described the taiga here as “virginal, primeval timberland.” From the altitude of the trees and the venerable length of the vines depending from them, I would guess that the taiga we saw was still original growth. That night, we camped above the small gorge of a river named for Arsenyev—the Arsenyevka. The sound of it was pleasant to sit beside; this was our first genuinely rushing stream. I stayed up for a while after Sergei and Volodya had gone to bed, listening to it and looking up at the stars and at the satellites tracking past. [Source: Ian Frazier, The New Yorker, August 10 and 17, 2009, Frazier is author of “Travels in Siberia” (2010) ]

“The next day, we continued winding generally eastward through the mountains. I noted villages called Uborka (Harvest), Shumnyi (Noisy), and Rudnyi (Oreville). Now we were in Arsenyev’s very footsteps. A little beyond Rudnyi, we crossed a mountain pass that hardly looked like one. This was the divide between the waters that flow roundabout to the Pacific via the Ussuri and the Amur, and those which drain down the front of the Sikhote-Alins and into the Pacific directly. At the crest of the divide, back among the roadside weeds, stood a cement obelisk on which was inscribed: “crossed over this pass: m. i. venyukov 1858*; N. M. PREZHEVALSKII* 1887*; V. K. ARSENYEV* 1906.”

Arsenyev’s passage across this divide happened during a mapping expedition guided by Dersu and described in detail in the book. The party continued from here until they came to the Pacific and the port village of Olga, where they were resupplied. Sergei said that we would also aim for Olga and camp near there.

“Often the taiga stood so close to the road that the vines almost touched the side of the car, and on the upgrades we were looking into the canopy. At one point in the movie “Dersu Uzala,” a tiger stalks Arsenyev’s party, and the Siberian tiger used for the scene was a splendid animal, all liquid motion and snarling growls. Though near extinction, the Siberian tiger has not yet been wiped out, and the thought that this Pacific forest—reminiscent in some ways of the American and Canadian Northwest—had tigers in it gave the shadows far back among the trees a new level of authority. I had been in a few forests that held grizzly bears, but a forest with tigers in it seemed even more mysterious and honorable.”

Kedrovaya Pad Reserve

Kedrovaya Pad Reserve (400 kilometers northeast of Vladivostok) is the oldest reserve in the Far East and the southernmost reserve of Primorye. Sikhote Alin Reserve and Kedrovaya Pad Reserve are the last homes of the Amur (Siberian) tiger. The largest wildlife sanctuary in the Far East. Kedrovaya (Cedar) Pad Reserve embraces 178.97 square kilometers (69.10 square miles) of forested mountains, coastline and clear rivers. Other animals found in reserves include brown bears, Amur leopard (of which only 40 to 50 remain), the Manchurian deer, roe deer, goral (a rare mountain goat), Asian black bears, salmon, lynx, wolf and squirrels with tassels on their ears, azure winged magpies and the emerald-colored papilio bianor maackii butterfly. Over 350 different species of bird have been seen here.

Kedrovaya (Cedar) Pad Reserve was one of the first officially organized reserves in Russia. The idea for establishing was raised at the beginning of the 20th century after the Trans-Siberian railway and built nearby and intensive development of the Ussuri region was accompanied by indiscriminate logging, forest fires, uncontrolled hunting. In 1908, the region created the first forest reserves, one of which was on Cedar River. Kedrovaya Pad Reserve, founded in 1916 close to the western shore of Amur Bay. Over time that status of the reserve was improved and the reserve was enlarged. In 2004 UNESCO designated the reserve as a biosphere.

Kedrovaya (Cedar) Pad Reserve is located in the Khasan district of Primorye Territory. The villages of Seaside, Perevoznaya, Cedar, Bezverkhova and Barabash located within a few kilometers of the reserve. . The reserve was established for the preservation and study of natural systems there of liana deciduous and mixed forests with hornbeam and black fir-broad-leaved forests and their animals and plants. The reserve provides shelter for two adult Amur leopard females and their offspring and one male. Among the rare species of insects found there are the excellent marshmallow beetle and Jankowski beetle.

The territory of the reserve is occupied by by two major low mountain ranges — the Gakkelevskaya and Suhorechensky — representing the extreme northeastern foothills of the Black (Changbai) Mountains, which are mainly in China and Korea. The length of the main Cedar River within the reserve is about 15 kilometers. The largest number of tributaries originating from Suhorechenskogo ridge flows into the forest, where many wild boars live. About 73.1 percent of the entire reserve is occupied by forests. The remaining area is occupied by scrub and secondary meadows resulting from logging in the past and especially forest fires.

The forest reserve contains numerous species of trees. The underbrush is represented by various bushes, that often blossom beautifully, such as early-flowering honeysuckle and Weigel, which produces fine-leaved mock orange flowers. Vines entwine tree trunks rising to a height of 30-35 meters. The diameter of the winding vines of wild grapes and the Amur Actinidia Argut reaches 10-15 centimeters. They are like giant snakes crawling from the ground and entangling shrubs and trees.

In places the reserve resembles a rainforest and it does have parallels with the temperate rain forests in coast British Columbia, Alaska and Washington state. Among the many plant species are Manchurian walnut, dimorfanta and aralia, with and velvet, spiny trunks, and several types of ferns. In the crevices of bark and crotches of trees attract epiphyte and small fern called Ussuri centipede.

Zov Tigra (“Roar of the Tiger”) National Park

Zov Tigra National Park(Near Lazo, 150 kilometers northeast of Vladivostok is a mountainous refuge for the Amur (Siberian) Tiger. Established in 2008, the park encompasses an area of 834 square difficult (322 square miles) on the southeast coast of Primorsky Krai. The park lies on both the eastern and western slopes of the southern Sikhote-Alin mountain range.,The relatively warm waters of the Sea of Japan are to the east, the Korean peninsula to the south, and China to the West. The terrain in rugged and difficult to access, with heavily forested taiga coexisting with tropical species of animals and birds. The park is relatively isolated from human development, and functions as a conservation reserve. Tourists may visit the portions of the park marked for recreation, but entry to the protected zones is only possible in the company of park rangers. The park’s name in English means "Call of the Tiger” or "Roar of the Tiger".

Zov Tigra National Park is occupied by Ussuri taiga and is located at the junction of Lazovsky, Chuguevsky, and Olginsky districts. The park covers 1,854-meter-high Oblachnaya mountain, the upper half of the Milogradovka's river basin, and sources of the Kievka River. There are more than 50 mountains more than 1000 meters high. The forest feature giant cedars, specimen trees, slender spruces entwined with gaily-coloured actinidia's lianas, emerald-green clusters of Amur grape and Schizandra brushwood.

Zov tigra was established in part as as a "source habitat" for the recovery of the Amur Tiger and its prey base. A survey in 2012 identified four Amur tigers resident in the park, and four more that visited the protected areas frequently. The base of prey consisted of 1,200 Manchurian deer, 800 Roe deer, and 99 Sika deer and 189 wild boars. These species make up some 85% of the Amur tiger's diet. Brown bears and lynx are relatively common in area. The Far Eastern Forest Cat is found in the broad-leaf and oak valleys. The critically endangered Amur Leopard has not been resident since the 1970s.

Amur Leopards

The Amur leopard inhabits an 800-mile long stretch of evergreen forest in the eastern Siberian taiga near the North Korean border. Named after the river that forms the border between Russia and China, they live in a narrow mountain chain that extends from Hanka Lake in the Russian Far East south to the borders of China and North Korea. It ranges further north than any leopard species, even the snow leopard.

Amur leopards weighs between 40 and 60 kilograms (90 and 140 pounds). They are reclusive, solitary creatures. They eat sitka deer and wild boars. Their numbers have declined as the numbers of their main food source, roe deer, have declined. They also suffer from declining numbers of sitka deer and wild boars. Leopards eat dogs of villagers to survive. Sometimes they are forced to make a single meal last for two weeks. Other times they reduced to scavenging for carrion. It’s winter coat has large spots.

Only 38 to 46 Amur leopard are believed to remain. Twenty to twenty-four in Russia. Fifteen in China and an unknown number in North Korea. They have been hurt by loss of habitat, loss of prey and poaching. Around 30 Amur leopards live in an area which borders China and is 150 kilometers long and 30 kilometers wide. At least 16 live in Nezhinkoye game reserve. This area contains many villages and is crisscrossed by roads, making survival problematic

Environmentalists have trouble securing funds to study the leopards. Most of what is known about them is based on studies conducted at Kedrovaya pad nature Reserve near Vladivostok. The Russian Academy of Science, the University of California and the International Wildlife Congress are studying the leopards using “phototraps”— motion sensitive cameras.

Land of Leopard National Park

Land of Leopard The National Park (200 kilometers west of Vladivostok) occupies 2,620 square kilometers and is located in the Khasansky, Nadezdinsky, Ussuriysky districts of Primorsky Krai as well as in the small area of Frunzenskiy district in Vladivostok. Kedrovaya Pad and Leopardovy reserves and number of other territories, with total area exceeding 2,800 square kilometers are as compounds of the National Park. The national park’s buffer zone covers about 800 square kilometers.

About 30 individual Amur leopards are thought to be living in the southwest area of Primorsky Krai. “Land of the Leopard” national park covers about 60 percent of the natural habitat occupied by the leopards and the main reason the park was set up was to preserve them. Many surviving Amur leopards live In the Nezhinkoye game reserve that is under partial protection of the Russian Pacific fleet. Hunting with dogs and hunting for fur animals is banned in the reserve. Deer and wild boars are fed. Some leopards used to follow hunters in hopes of snatching an easy meal. Work on the world’s longest pipeline — between Siberia and the Sea of Japan — was suspended in 2005 due to ecological concerns, among them the fate of the Amur leopard, whose territory would be bisected by the pipeline.

The “Land of Leopard” is divided into several zones, the smallest of which is a 230-square-kilometer conservation zone that you can’t visit without special permission. Other zones have a simplified visiting regime. Guided trips are allowed in the “specially protected” zone. The 7950-square-kilometer recreational zone allows more touristic activity. The “Leopard Trail” is the first tourist route, developed in the National Park. The 770-square-kilometer administrative zone accommodates villagers and interests of other people living in the territory of the National Park.

Leopardovy Sanctuary

Leopardovy Sanctuary (200 kilometers west of Vladivostok) embraces 1,694.29 square kilometers of the “Barsovy” and “Borisovskoe Plato” sanctuaries in the Khasansky, Ussuriysky, and Nadezhdinskiy districts. The state biological sanctuary “Barsovy” was founded in 1979 to preserve and restore not only the endangered animal species such as Siberian Tiger and Amur Leopard but also their natural habitat. The animal sanctuary “Borisovskoe Plato” was created in 1996 to conserve and increase the population number of Amur leopard; Siberian tiger and other threatened animals.

The sanctuary's natural environment is highly favorable for the forest faun's inhabitation. The low-level mountain ranges deeply dissected with the river valleys, extended rock masses, and plateau-like mountains create mosaic of forest, tree and shrubbery vegetation. Secondary broadleaved forests prevail here. Primary forests with fir trees, cedars and khingam fir remain in the west and northwest part of the sanctuary. The plateau-like mountains are covered with the leafed forest.

Amur leopard is the main protected species here.Siberian tiger, Asian black bear, leopard cat and other animals are also placed under special protection. There are six ungulates species such as Amur goral, Manchurian wapiti, wild boar, musk deer, roe deer, and deer in the sanctuary. Lot of rare vascular plants grows here, some of them such as water caltrop, stipa baicalensis, nepeta manchuriensis are not presented even in the neighboring “Kedrovaya Pad” reserve. More than 150 species of birds nest in the sanctuary and around 100 species traverse its territory or make stopover here during the migration period. It must be stressed that “Leopardovy” sanctuary is the only place of nesting for some bird species in this part of Primorsky krai. 15 of these species are threatened with extinction. Over 40 IUCN Red List insect species inhabit here, what is more some of them occur exceptionally at the sanctuary's territory.

This district has a monsoon climate. Its specific trait is the variability of the airstreams direction in the summer and winter seasons. Plenty of rivers and streams run at the sanctuary’s territory. There are no large lakes. The biggest one, Krivoe lake, covers 11 hectares. All types of hunting, commercial fishery, timber felling, resource development, ploughing the ground, and application of chemicals are prohibited here. Beyond that, public visiting, amateur fishery, and gathering wild harvest are brought under regulation. The sanctuary contains some populated places such as Barabash settlement and military firing range with total area in 3,490 squate kilometers A considerable part of the territory is the border territory separated from the rest of area by the plowed strip.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Federal Agency for Tourism of the Russian Federation (official Russia tourism website russiatourism.ru ), Russian government websites, UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Yomiuri Shimbun and various books and other publications.

Updated in September 2020

- Google+

Page Top

This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been authorized by the copyright owner. Such material is made available in an effort to advance understanding of country or topic discussed in the article. This constitutes 'fair use' of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. If you are the copyright owner and would like this content removed from factsanddetails.com, please contact me.

- Open access

- Published: 03 June 2024

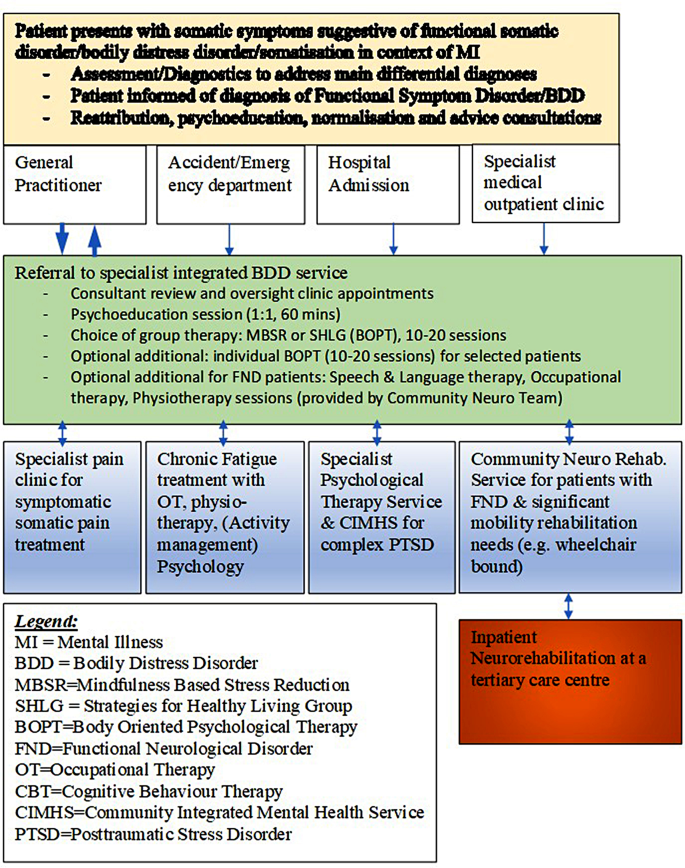

Integrated care model for patients with functional somatic symptom disorder – a co-produced stakeholder exploration with recommendations for best practice

- Frank Röhricht 1 , 2 ,

- Carole Green 3 ,

- Maria Filippidou 4 ,

- Simon Lowe 5 ,

- Nicki Power 1 , 2 ,

- Sara Rassool 6 ,

- Katherine Rothman 7 ,

- Meera Shah 8 &

- Nina Papadopoulos 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 698 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

71 Accesses

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Functional somatic symptoms (FFS) and bodily distress disorders are highly prevalent across all medical settings. Services for these patients are dispersed across the health care system with minimal conceptual and operational integration, and patients do not currently access therapeutic offers in significant numbers due to a mismatch between their and professionals’ understanding of the nature of the symptoms. New service models are urgently needed to address patients’ needs and to align with advances in aetiological evidence and diagnostic classification systems to overcome the body–mind dichotomy.

A panel of clinical experts from different clinical services involved in providing aspects of health care for patients with functional symptoms reviewed the current care provision. This review and the results from a focus group exploration of patients with lived experience of functional symptoms were explored by the multidisciplinary expert group, and the conclusions are summarised as recommendations for best practice.

The mapping exercise and multidisciplinary expert consultation revealed five themes for service improvement and pathway development: time/access, communication, barrier-free care, choice and governance. Service users identified four meta-themes for best practice recommendations: focus on healthcare professional communication and listening skills as well as professional attributes and knowledge base to help patients being both believed and understood in order to accept their condition; systemic and care pathway issues such as stronger emphasis on primary care as the first point of contact for patients, resources to reduce the length of the patient journey from initial assessment to diagnosis and treatment.

We propose a novel, integrated care pathway for patients with ‘functional somatic disorder’, which delivers care according to and working with patients’ explanatory beliefs. The therapeutic model should operate based upon an understanding of the embodied nature of patient’s complaints and provide flexible access points to the care pathway.

Peer Review reports