- Open access

- Published: 04 September 2021

Journey mapping as a novel approach to healthcare: a qualitative mixed methods study in palliative care

- Stephanie Ly 1 ,

- Fiona Runacres 1 , 2 , 3 &

- Peter Poon 1 , 2

BMC Health Services Research volume 21 , Article number: 915 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

16 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

Journey mapping involves the creation of visual narrative timelines depicting the multidimensional relationship between a consumer and a service. The use of journey maps in medical research is a novel and innovative approach to understanding patient healthcare encounters.

To determine possible applications of journey mapping in medical research and the clinical setting. Specialist palliative care services were selected as the model to evaluate this paradigm, as there are numerous evidence gaps and inconsistencies in the delivery of care that may be addressed using this tool.

A purposive convenience sample of specialist palliative care providers from the Supportive and Palliative Care unit of a major Australian tertiary health service were invited to evaluate journey maps illustrating the final year of life of inpatient palliative care patients. Sixteen maps were purposively selected from a sample of 104 consecutive patients. This study utilised a qualitative mixed-methods approach, incorporating a modified Delphi technique and thematic analysis in an online questionnaire.

Our thematic and Delphi analyses were congruent, with consensus findings consistent with emerging themes. Journey maps provided a holistic patient-centred perspective of care that characterised healthcare interactions within a longitudinal trajectory. Through these journey maps, participants were able to identify barriers to effective palliative care and opportunities to improve care delivery by observing patterns of patient function and healthcare encounters over multiple settings.

Conclusions

This unique qualitative study noted many promising applications of the journey mapping suitable for extrapolation outside of the palliative care setting as a review and audit tool, or a mechanism for providing proactive patient-centred care. This is particularly significant as machine learning and big data is increasingly applied to healthcare.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Patterns of healthcare utilisation are evolving in response to the ageing population and increasing burden of chronic disease. There is an urgent need to ensure timely proactive medical care, effective and efficient resource deployment, while averting unnecessary, often distressing, emergency department (ED) presentations, admissions and conveyor belt medicine. A key area of medicine able to address these issues is palliative care.

Central to optimal delivery of palliative care is timely initiation [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. However, differing patient, illness trajectory and clinical factors have resulted in inconsistencies in the degree of care provided [ 4 , 5 ]. This has subsequently translated into significant variability in palliative care research and limitations in applying international evidence to clinical practice [ 6 ]. The utilisation of journey mapping has the potential to address these inconsistencies and to our knowledge, this research is the first of its kind.

Journey mapping is a relatively new approach in medical research that has been adapted from customer service and marketing research [ 7 ]. It is gaining increasing recognition for its ability to organise complex multifaceted data from numerous sources and explore interactions across care settings and over time. Medical journey mapping involves creating narrative timelines, by incorporating markers of the patient experience with healthcare service encounters. Integrating diverse components of the patient healthcare journey provides a holistic perspective of the relationships between the different elements that may guide directions for change and service improvement. As medical journey mapping is still in its infancy, there is an absence of literature exploring implementation. Of the existing literature, journey mapping techniques are described mainly in process papers, outlining their potential utility in observing healthcare delivery and patient outcomes [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. However journey mapping paradigms have broader significance across healthcare, especially in an environment for which machine learning, big data and artificial intelligence is maturing.

We aimed to determine whether journey mapping could contribute to the improvement of patient-centred medical research in a palliative care setting and provide new insight into possible “pivot-points” or moments of care that could be altered to improve care delivery. Specifically, we sought to determine whether journey maps were able to assist in capturing a holistic, longitudinal and more integrative patient history whilst outlining healthcare provision and identifying gaps in care.

Study design

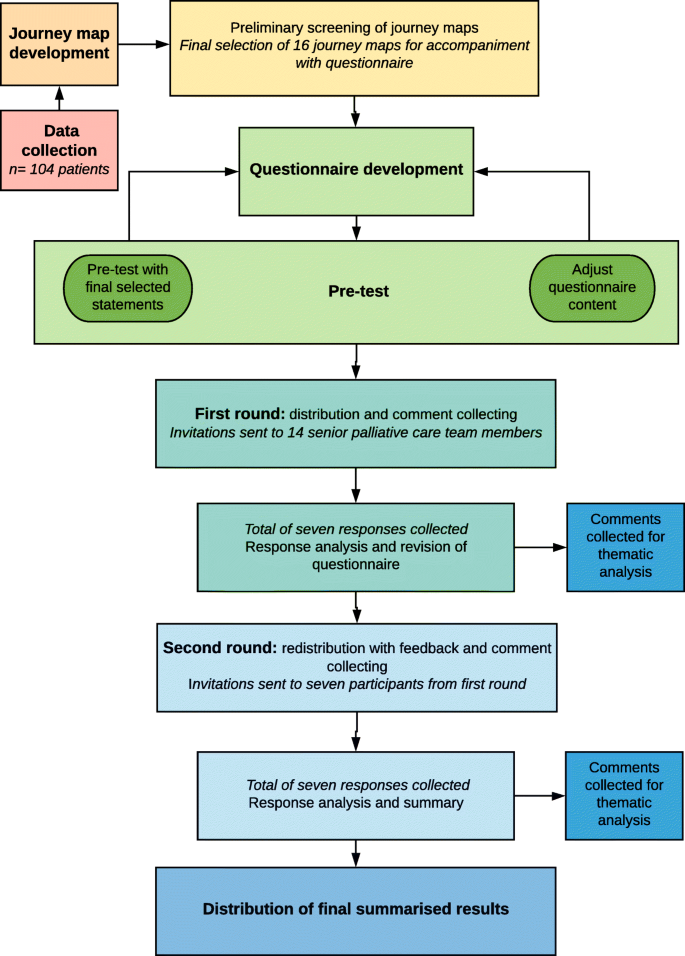

We performed a qualitative mixed-methods analysis of a journey mapping tool. The tool was purpose-developed and sample journey maps were derived from the scanned medical records of palliative care patients. A panel of specialist palliative care providers were then involved in an online questionnaire combining a modified Delphi approach with inductive thematic analysis. Figure 1 depicts a flow diagram of the methodology.

Flow chart detailing data collection, journey map development and analysis. This figure illustrates the phases and processes of this study. Data was collected from a retrospective cohort of 104 palliative care patients and journey maps were subsequently developed. Preliminary screening of the journey maps was performed to obtain a purposive sample that best highlighted the breadth of information and healthcare encounters captured within the journey maps. A total of 16 maps were selected for further analysis. Following questionnaire development and pre-test, questionnaires were distributed, and responses collected and analysed over two rounds to obtain consensus. Free-text comments from both rounds were collected for thematic analysis

All methods were carried out and reported in accordance with Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) guidelines and Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research (COREQ) criteria for reporting qualitative studies.

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from Monash Health Human Research Ethics Committee Monash Health Ref: RES-29-0000-071Q) and Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID: 18,853).

Data was collected from a retrospective cohort of 104 consecutive palliative care patients from a major tertiary hospital network in Melbourne, Australia. Inclusion criteria were patients greater than 18 years of age who had died in hospital between the 1st of August 2018 and 31st of October 2018, had at least one inpatient palliative care admission in their last year of life and scanned medical records data spanning at least three months’ duration. This sample size was considered sufficient to incorporate a varied and representative sample of palliative care patients encountered in the tertiary hospital.

Following data collection, a Python Software-based code was designed to extract de-identified data and create journey map visuals. All 104 journey maps were independently screened by two investigators (PP and FR) and a purposive sample of 16 maps was selected for analysis based on seven criteria for informative value. The criteria that the 104 maps were assessed on included their ability to provide insight into the initiation, triggers, delivery and barriers of palliative care, SPICT scores, pivot points and disease trajectories.

Modified Delphi approach and thematic analysis

A qualitative mixed-methods approach involving thematic analysis and a modified Delphi technique was utilised as an explorative analysis of expert opinion. The consensus agreement was used to reinforce and confirm the patterns of significance identified through thematic analysis. In combining these two approaches, there was greater flexibility in responses and additional structure to support analysis.

The modified Delphi approach used in this study was adapted from the enhanced Delphi method described by Yang et al. [ 13 ] and consisted of a questionnaire pre-test and two rounds of questionnaire distribution. A total of 14 email invitations were sent to a purposive sample of seven senior palliative care physicians and seven palliative care nurse consultants across two palliative care inpatient units within a major tertiary hospital network in Melbourne, Australia. The emails contained an explanatory statement, a questionnaire link and the file containing the 16 de-identified journey maps.

The questionnaires consisted of 16 statements per journey map, covering eight palliative care domains: palliative care triggers, initiation, delivery, outcomes, barriers, pivot-points, needs assessment (using the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool, SPICT) and the utility of advanced care plans. An additional nine statements assessed the utility of the journey map approach (see Table 2 ). All statements were ranked using Likert scales. A four-point Likert scale including the options: insufficient information, disagree, neither agree nor disagree and agree was used to assess individual journey maps. A five-point Likert scale including options: strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat agree and strongly agree was used to assess the journey mapping approach. For analysis of consensus, the results were categorised to reflect overall agreement by using a three-point scale consisting of disagree, neutral and agree . Consensus was defined as agreement of greater than 70 % of respondents in any one of these three categories. Following the first round, all consensus statements were determined and participants were sent a second questionnaire containing anonymous feedback from the first round and statements which did not reach consensus for re-evaluation using the condensed three-point Likert scale.

Following each palliative care domain, free-text fields were included to collect comments and provide data for inductive thematic analysis. Analysis of the free-text comments from both rounds was guided by Braun and Clarke’s phases of thematic analysis [ 14 ]. The codes and themes were derived from the data using NVivo 12 Plus software to generate nodes, initial codes and preliminary subthemes. Candidate themes were reviewed by two additional investigators (PP and FR) to ensure consistency and the final themes were defined. Providing participants with the opportunity to review de-identified feedback through the Delphi questionnaire enabled discussion, reflection and clarification of comments, thus achieving thematic saturation with a smaller group of participants.

Additional steps were taken to increase trustworthiness of the qualitative data per Lincoln and Guba’s criteria for credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability across all phases of analysis [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Triangulation of the methods, researchers and analysts aimed to increase consistency and accuracy, whilst reducing interpretation errors and the effects of bias. Thorough audit trails and reflexive journaling were maintained. The use of the online questionnaire with free-text fields for thematic data collection limited the role of the researcher and the potential for associated bias.

While this study also produced findings relevant to current issues of palliative care delivery, we will for the purpose of this paper, present results specific to the clinical utility of journey maps.

The journey maps

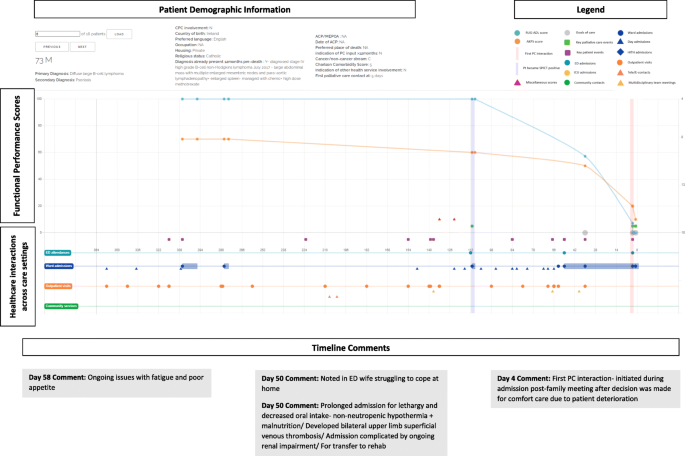

Figure 2 depicts one of the 16-sample journey maps analysed by participants and illustrates the key elements of a map. While journey maps are interactive visualisations with options for providing additional information summarising patient healthcare encounters, we are unable to fully convey the dynamic functions of the mapping tool in this paper. The journey map in Fig. 2 illustrates the final year of life of a 73 year old male patient with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Screen capture of Journey Map 6. A screen capture of one of the 16 interactive journey maps that was analysed by the Delphi panel. The lower segment of the map depicts healthcare interactions that occurred in hospital and in the community. Delphi participants are able to hover over specific health service touch points to obtain more information about the specific interaction that occurred. The upper segment represents functional performance scores using two different tools- the Australian Karnofsky Performance Scale (AKPS) and the Resource Utilisation Groups-Activities of Daily Living (RUG-ADL). The orange vertical line indicates when palliative care needs first presented using the SPICT screening tool. The vertical purple line indicates when specialist palliative care was initiated. Delphi participants were able to analyse the maps and respond to statements on the palliative care provided

The map reveals that at day 112 prior to death, palliative care needs were noted using the SPICT screening tool. It is also at this point that the patient’s functional performance scores began to decline, with patient notes from day admissions and clinic visits also documenting poor tolerance of chemotherapy side effects, fatigue, anorexia and weight loss. In response to this pattern of decline, participants noted that there was an opportunistic role for community palliative care support that was missed and could have potentially negated the need for the final ED admission.

“Onc (sic)(oncology) outpatient notes describing symptoms, deterioration, carer distress… Community pall care (sic)(palliative care) could have been helpful” – Participant 2, Journey Map (JM) 6.

Another major pivot-point occurred during the patient’s admission to ED on day 50 when notes indicated that the patient’s wife was struggling to cope with care at home. Given the nature of the prolonged admission with multiple complications that followed, Delphi participants questioned the suitability of the transfer to the rehabilitation ward.

“Symptoms and functional decline appear to be related to lymphoma and not an acute illness. More appropriate for pall care (sic) than rehab (sic)(rehabilitation).” – Participant 6, JM6.

Additionally, the decision to initiate palliative care only four days prior to death was delayed and there was a role for earlier palliative care involvement.

“Clearly PC (sic)(palliative care) involvement inadequate and was a later referral for terminal care only” – Participant 1, JM6.

“Pt (sic)(patient) would have benefitted from earlier palliative care referral” – Participant 7, JM6.

Through the maps, participants were able to observe patterns of deterioration with a broader view of continuity of care and determine pivot-points, where the involvement of specialist palliative care had the potential to improve the patient experience.

Modified Delphi

The two Delphi rounds were conducted over 31 days with the first round taking 13 days and the second round spanning 18 days. A total of seven responses were collected from the first round of the online Delphi questionnaire. Six members of the medical staff and one member of the nursing team responded, representing a 50 % response rate. All seven participants completed the questionnaire in full. For the second round, all first round participants were re-contacted and invited to participate. All seven participants from the first round agreed to participate, attributing to a 100 % second round response rate and 100 % questionnaire completion rate. Participant characteristics have been described in Table 1 . All participants are senior palliative care team members.

The statements assessing journey map utility are shown in Table 2 . As there was a strong overall consensus following the first round of the Delphi questionnaire, these statements were not rechallenged in a second round. However free-text fields were included to allow participants to provide any further comments.

Thematic analysis

Following analysis of all free-text comments, the following themes were derived regarding the applications of the journey mapping tool: (1) design and information, (2) longitudinal care and the patient trajectory and (3) opportunities for care improvement. These are discussed with supporting quotations listed in Table 3 .

Theme 1: tool design and information

A large determinant of the practicality of the tool relates to its design. Participants provided feedback regarding the design and informational elements of the journey mapping tool used in this study.

Aspects of the interface

Participants found that there were certain elements of the journey maps that limited functionality of the tool, however these were associated with the specific design of the tool interface, rather than the actual components underlying the journey mapping approach. Participants responded well to the concept of a visual representation of patient information and the timeline view of care that was constructed.

Catering information needs

Given the palliative care specific focus on patient care presented in these maps, participants found that at times there was an excess of unnecessary information and insufficient palliative care appropriate information. The absence of objective measures of quality of life also restricted the ability of participants to determine whether outcomes were improved as a result of interventions.

Theme 2: Longitudinal care and the patient trajectory

The benefits of conveying patient information and healthcare encounters in the form of journey maps were also recognised. Journey maps provided a patient-centred focus of care that characterises patient healthcare interactions within a longitudinal trajectory rather than individual care episodes as is standard in conventional medical records. In doing so, patterns of the disease trajectory and also patient decline can be mapped to provide more proactive patient care.

Theme 3: Opportunities for care improvement

The benefits of having the journey mapping tool and its utility if incorporated into patient care were also explored, with participants noting numerous possible applications and opportunities to improve patient care.

Identifying barriers and missed opportunities for care

By framing the patient healthcare experience as a longitudinal and continuous journey, participants were able to recognise missed opportunities to address barriers and initiate more timely palliative care.

Clinical applications

Participants also noted that journey maps were a useful tool for identifying gaps in care provision and underlying barriers to initiation and delivery. This could assist clinicians with recognition of pivot-points and opportunities to enhance care by pre-emptively managing issues. Additionally, journey maps presented possible applications as a review or screening tool to evaluate patient care needs and enable better patient-centred care practices both in the clinical and research setting.

Findings from both the modified Delphi and thematic analysis appeared congruent, with the consensus consistent with emerging themes.

Journey mapping is a novel approach to reviewing patient healthcare interactions over time and across care settings to identify potential pivot points, which in turn can facilitate timely healthcare and promote proactive delivery of patient-centred care. Our research has focused on palliative care as the model to explore this approach, especially given its importance in an ageing population and considering many aspects of care are ubiquitous to this cohort.

Variation and inconsistencies in palliative care initiation and delivery have limited the applicability and role of research in informing evidence-based practice [ 6 ]. A journey map approach may provide one solution to address these challenges. The journey mapping tool used in this study was found to enable a patient-centred focus to the clinician’s perspective, increasing opportunities to pro-actively identify pivot-points and deliver more effective patient care.

In comparison to conventional medical records, journey maps link patient healthcare encounters longitudinally, promoting continuity and a holistic understanding of care across settings and over time. As described in conceptual studies, journey maps offer a perspective that takes into account the more dynamic and multidimensional aspects of healthcare interactions to facilitate enhanced insight into the patient experience within medical research [ 10 , 18 ]. This enables a more integrated interpretation and awareness of individual episodes of care and how these contribute to a patient’s overall health and their interaction with health services. Our participants also noted that journey mapping enabled greater emphasis on particular patient outcomes that may be difficult to observe or measure using conventional research methods. The journey mapping tool was also able to highlight gaps in care and facilitate recognition of patterns of disease progression and deterioration with a greater emphasis on patient needs and experiences.

The use of the journey mapping approach has further enabled identification of barriers and potential biases to providing effective care. This study confirms that journey mapping as a tool is effective at identifying specific barriers and trends in care provision and increase opportunities for care providers to pro-actively and appropriately address these.

Journey maps have traditionally been used in research to review and analyse the consumer experience and provide feedback on avenues for development [ 7 ]. Our panel consensus affirmed that journey mapping had applications as a clinical audit tool to identify gaps in care and opportunities for improvement when used to assess retrospective patient experiences. This is consistent with known utilities of previous journey mapping tools. Other identified benefits included potential to achieve better collaboration between healthcare providers, enabling smoother transitions of care and improving communication between healthcare providers and patients.

Limitations of this study include the design and interface of the journey mapping tool. Following a thorough search, pre-existing journey mapping software and tools were considered inappropriate for this study as they were oversimplified, unable to convey complex information appropriately and not designed for use in a medical setting. Consequently, self-designing a tool was considered the most suitable approach. The technical limitations identified did not reflect the utility of the journey mapping paradigm.

The retrospective nature of this study prohibits direct patient feedback. Consequently, the patient and caregiver perspective, including quality of life and symptom burden experienced were not well represented. Future research utilising a prospective approach with patient and caregiver involvement is needed to address these research gaps.

The response rate to the initial Delphi questionnaire was only 50 % due to time constraints and limited ability to accommodate delayed responses, however the response rate to the second Delphi questionnaire was 100 %. While this does limit the diversity of responses, it suggests good retention and engagement of involved participants with meaningful contributions.

The size of the Delphi panel in this study was seven. Studies have noted that smaller panels are still able to provide effective and reliable results and a minimum panel size of seven is considered suitable in most cases [ 19 , 20 ]. Our modified approach complied with this. Despite being a single institution study, the participants come from a diverse clinical background covering multiple domains of specialty palliative care, henceforth reducing potential bias. This study demonstrates that there is a role for journey mapping in clinical practice, however, considerations must be made for future design. Given the volume of patient data available, the amount of information presented needs to be appropriately moderated to provide clarity and best utilisation of the resources available. With the gradual transition of most health services from paper medical records to electronic medical records, the inclusion of a journey mapping tool into clinical practice is becoming more feasible. As medical technology continues to grow, the potential for incorporation of artificial intelligence, machine learning and big data into journey maps could be the key to providing pro-active, holistic patient-centred care that pre-emptively anticipates patient needs.

This study is one of the first to use a journey mapping tool in clinical practice to explore the healthcare journey and patient experience on a larger scale. The maps were used to depict a more fluid and continuous interpretation of the patient healthcare experience which enabled a more holistic and patient-centred analysis of palliative care provision. Furthermore, this is one of the first medical journey mapping studies to consider and propose potential pivot-points and opportunities for changes in the delivery of care. The use of journey maps can enhance the holistic patient healthcare experience and enable better patient-centred care not only in the palliative care setting, but also more broadly across healthcare from both a research and clinical practice perspective. Further application studies in other contexts are required.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the confidential nature of the patient data, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–42.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, et al. Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(13):1438–45.

Article Google Scholar

King JD, Eickhoff J, Traynor A, Campbell TC. Integrated onco-palliative care associated with prolonged survival compared to standard care for patients with advanced lung cancer: a retrospective review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(6):1027–32.

Hawley P. Barriers to access to palliative care. Palliative Care. 2017;10:1178224216688887.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rodriguez KL, Barnato AE, Arnold RM. Perceptions and utilization of palliative care services in acute care hospitals. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(1):99–110.

Evans CJ, Harding R, Higginson IJ. Morecare. ‘Best practice’ in developing and evaluating palliative and end-of-life care services: a meta-synthesis of research methods for the MORECare project. Palliat Med. 2013;27(10):885–98.

Gibbons S. Journey Mapping 101. 2018; https://www.nngroup.com/articles/journey-mapping-101/ .

Crunkilton DD. Staff and client perspectives on the Journey Mapping online evaluation tool in a drug court program. Eval Program Plan. 2009;32(2):119–28.

Westbrook JI, Coiera EW, Sophie Gosling A, Braithwaite J. Critical incidents and journey mapping as techniques to evaluate the impact of online evidence retrieval systems on health care delivery and patient outcomes. Int J Med Inform. 2007;76(2–3):234–45.

McCarthy S, O’Raghallaigh P, Woodworth S, Lim YL, Kenny LC, Adam F. An integrated patient journey mapping tool for embedding quality in healthcare service reform. J Decision Syst. 2016;25(sup1):354–68.

Hide E, Pickles J, Maher L. Experience based design: a practical method of working with patients to redesign services. Clin Gov. 2008;13(1):51–8.

Trebble TM, Hansi N, Hydes T, Smith MA, Baker M. Process mapping the patient journey: an introduction. BMJ. 2010;341:c4078.

Yang T-H. Case study: application of enhanced Delphi method for software development and evaluation in medical institutes. Kybernetes. 2016;45(4):637–49.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16(1):1609406917733847.

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1985.

Book Google Scholar

Cohen D, Crabtree B. Qualitative Research Guidelines Project. 2006; http://www.qualres.org/HomeRefl-3703.html .

Ben-Tovim DI, Dougherty ML, O’Connell TJ, McGrath KM. Patient journeys: the process of clinical redesign. Med J Aust. 2008;188(S6):S14–7.

PubMed Google Scholar

Linstone H. The Delphi technique. Handbook of Futures Research. Westport: Greenwood; 1978.

Google Scholar

Akins RB, Tolson H, Cole BR. Stability of response characteristics of a Delphi panel: application of bootstrap data expansion. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:37–37.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and extend our thanks to Kevin Shi who contributed to the Python code used for the journey map visuals.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Medicine Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Clayton, VIC, Australia

Stephanie Ly, Fiona Runacres & Peter Poon

Supportive & Palliative Care Department, McCulloch House, Monash Medical Centre, 246 Clayton Road, VIC, 3168, Clayton, Australia

Fiona Runacres & Peter Poon

Calvary Health Care Bethlehem, Parkdale, VIC, Australia

Fiona Runacres

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conceptualisation PP. Methodology: PP, FR, SL. Formal analysis PP, FR, SL. Investigation: PP, FR, SL. Writing –original draft: SL. Writing- Review and Editing: PP, FR. Supervision : PP, FR. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Peter Poon .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from Monash Health Human Research Ethics Committee Monash Health Ref: RES-29-0000-071Q) and Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID: 18853). Informed consent from patients was not required as this was a retrospective audit of pre-existing available data which was de-identified prior to analysis. All participants of the Delphi questionnaire were provided with an explanatory statement and by completing and returning the questionnaires, consent was implied.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ly, S., Runacres, F. & Poon, P. Journey mapping as a novel approach to healthcare: a qualitative mixed methods study in palliative care. BMC Health Serv Res 21 , 915 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06934-y

Download citation

Received : 10 April 2021

Accepted : 24 August 2021

Published : 04 September 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06934-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Patient journey mapping

- Health services research

- Palliative care

- Illness trajectory

- Proactive healthcare

- Medical informatics

- Patient-centred care

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Breast cancer patient experiences through a journey map: A qualitative study

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Clinical Psychology and Psychobiology Department, Faculty of Psychology, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Medical Oncology Department Hospital Universitario Central of Asturias, Oviedo, Spain

Roles Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Social Psychology and Quantitative Psychology Department, Faculty of Psychology, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Affiliation Medical Oncology Department, Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos, Madrid, Spain

Affiliation Medical Oncology Department, Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense, Ourense, Spain

Affiliation Medical Oncology Department, Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid, Spain

Affiliation Medical Oncology Department, Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Elche, Spain

Affiliation Medical Oncology Department, Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón, Madrid, Spain

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

- Laura Ciria-Suarez,

- Paula Jiménez-Fonseca,

- María Palacín-Lois,

- Mónica Antoñanzas-Basa,

- Ana Fernández-Montes,

- Aranzazu Manzano-Fernández,

- Beatriz Castelo,

- Elena Asensio-Martínez,

- Susana Hernando-Polo,

- Caterina Calderon

- Published: September 22, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257680

- Reader Comments

Registered Report Protocol

21 Dec 2020: Ciria-Suarez L, Jiménez-Fonseca P, Palacín-Lois M, Antoñanzas-Basa M, Férnández-Montes A, et al. (2020) Ascertaining breast cancer patient experiences through a journey map: A qualitative study protocol. PLOS ONE 15(12): e0244355. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244355 View registered report protocol

Breast cancer is one of the most prevalent diseases in women. Prevention and treatments have lowered mortality; nevertheless, the impact of the diagnosis and treatment continue to impact all aspects of patients’ lives (physical, emotional, cognitive, social, and spiritual).

This study seeks to explore the experiences of the different stages women with breast cancer go through by means of a patient journey.

This is a qualitative study in which 21 women with breast cancer or survivors were interviewed. Participants were recruited at 9 large hospitals in Spain and intentional sampling methods were applied. Data were collected using a semi-structured interview that was elaborated with the help of medical oncologists, nurses, and psycho-oncologists. Data were processed by adopting a thematic analysis approach.

The diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer entails a radical change in patients’ day-to-day that linger in the mid-term. Seven stages have been defined that correspond to the different medical processes: diagnosis/unmasking stage, surgery/cleaning out, chemotherapy/loss of identity, radiotherapy/transition to normality, follow-up care/the “new” day-to-day, relapse/starting over, and metastatic/time-limited chronic breast cancer. The most relevant aspects of each are highlighted, as are the various cross-sectional aspects that manifest throughout the entire patient journey.

Conclusions

Comprehending patients’ experiences in depth facilitates the detection of situations of risk and helps to identify key moments when more precise information should be offered. Similarly, preparing the women for the process they must confront and for the sequelae of medical treatments would contribute to decreasing their uncertainty and concern, and to improving their quality-of-life.

Citation: Ciria-Suarez L, Jiménez-Fonseca P, Palacín-Lois M, Antoñanzas-Basa M, Fernández-Montes A, Manzano-Fernández A, et al. (2021) Breast cancer patient experiences through a journey map: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 16(9): e0257680. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257680

Editor: Erin J. A. Bowles, Kaiser Permanente Washington, UNITED STATES

Received: February 17, 2021; Accepted: September 3, 2021; Published: September 22, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Ciria-Suarez et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Relevant anonymized data excerpts from the transcripts are in the main body of the manuscript. They are supported by the supplementary documentation at 10.1371/journal.pone.0244355 .

Funding: This work was funded by the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology (SEOM) in 2018. The sponsor of this research has not participated in the design of research, in writing the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer and the one that associates the highest mortality rates among Spanish women, with 32,953 new cases estimated to be diagnosed in Spain in 2020 [ 1 ]. Thanks to early diagnosis and therapeutic advances, survival has increased in recent years [ 2 ]. The 5-year survival rate is currently around 85% [ 3 , 4 ].

Though high, this survival rate is achieved at the expense of multiple treatment modalities, such as surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and hormone therapy, the side effects and sequelae of which can interfere with quality-of-life [ 5 ]. Added to this is the uncertainty surrounding prognosis; likewise, life or existential crises are not uncommon, requiring great effort to adjust and adapt [ 6 ]. This will not only affect the patient psychologically, but will also impact their ability to tolerate treatment and their socio-affective relations [ 7 ].

Several medical tests are performed (ultrasound, mammography, biopsy, CT, etc.) to determine tumor characteristics and extension, and establish prognosis [ 8 ]. Once diagnosed, numerous treatment options exist. Surgery is the treatment of choice for non-advanced breast cancer; chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and hormone therapy are adjuvant treatments with consolidated benefit in diminishing the risk of relapse and improving long-term survival [ 9 ]. Breast cancer treatments prompt changes in a person’s physical appearance, sexuality, and fertility that interfere with their identity, attractiveness, self-esteem, social relationships, and sexual functioning [ 10 ]. Patients also report more fatigue and sleep disturbances [ 11 ]. Treatment side effects, together with prognostic uncertainty cause the woman to suffer negative experiences, such as stress in significant relationships, and emotions, like anxiety, sadness, guilt, and/or fear of death with negative consequences on breast cancer patients’ quality-of-life [ 10 , 12 ]. Once treatment is completed, patients need time to recover their activity, as they report decreased bodily and mental function [ 13 ], fear of relapse [ 14 ], and changes in employment status [ 15 ]. After a time, there is a risk of recurrence influenced by prognostic factors, such as nodal involvement, size, histological grade, hormone receptor status, and treatment of the primary tumor [ 16 ]. Thirty percent (30%) of patients with early breast cancer eventually go on to develop metastases [ 17 ]. There is currently no curative treatment for patients with metastatic breast cancer; consequently, the main objectives are to prolong survival, enhance or maintain quality-of-life, and control symptoms [ 17 , 18 ]. In metastatic stages, women and their families are not only living with uncertainty about the future, the threat of death, and burden of treatment, but also dealing with the existential, social, emotional, and psychological difficulties their situation entails [ 18 , 19 ].

Supporting and accompanying breast cancer patients throughout this process requires a deep understanding of their experiences. To describe the patient’s experiences, including thoughts, emotions, feelings, worries, and concerns, the phrase “patient voice” has been used, which is becoming increasingly common in healthcare [ 20 ]. Insight into this “voice” allows us to delve deeper into the physical, emotional, cognitive, social, and spiritual effects of the patient’s life. This narrative can be portrayed as a “cancer journey", an experiential map of patients’ passage through the different stages of the disease [ 21 ] that captures the path from prevention to early diagnosis, acute care, remission, rehabilitation, possible recurrence, and terminal stages when the disease is incurable and progresses [ 22 ]. The term ‘patient journey’ has been used extensively in the literature [ 23 – 25 ] and is often synonymous with ‘patient pathway’ [ 26 ]. Richter et al. [ 26 ] state that there is no common definition, albeit in some instances the ‘patient journey’ comprises the core concept of the care pathway with greater focus on the individual and their perspective (needs and preferences) and including mechanisms of engagement and empowerment.

While the patient’s role in the course of the disease and in medical decision making is gaining interest, little research has focused on patient experiences [ 27 , 28 ]. Patient-centered care is an essential component of quality care that seeks to improve responsiveness to patients’ needs, values, and predilections and to enhance psychosocial outcomes, such as anxiety, depression, unmet support needs, and quality of life [ 29 ]. Qualitative studies are becoming more and more germane to grasp specific aspects of breast cancer, such as communication [ 27 , 30 ], body image and sexuality [ 31 , 32 ], motherhood [ 33 ], social support [ 34 ], survivors’ reintegration into daily life [ 13 , 15 ], or care for women with incurable, progressive cancer [ 17 ]. Nevertheless, few published studies address the experience of women with breast cancer from diagnosis to follow-up. These include a clinical pathway approach in the United Kingdom in the early 21st century [ 35 ], a breast cancer patient journey in Singapore [ 25 ], a netnography of breast cancer patients in a French specialized forum [ 28 ], a meta-synthesis of Australian women living with breast cancer [ 36 ], and a systematic review blending qualitative studies of the narratives of breast cancer patients from 30 countries [ 37 ]. Sanson-Fisher et al. [ 29 ] concluded that previously published studies had examined limited segments of patients’ experiences of cancer care and emphasized the importance of focusing more on their experiences across multiple components and throughout the continuum of care. Therefore, the aim of this study is to depict the experiences of Spanish breast cancer patients in their journey through all stages of the disease. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies that examine the experience of women with breast cancer in Spain from diagnosis through treatment to follow-up of survivors and those who suffer a relapse or incurable disease presented as a journey map.

A map of the breast cancer patient’s journey will enable healthcare professionals to learn first-hand about their patients’ personal experiences and needs at each stage of the disease, improve communication and doctor-patient rapport, thereby creating a better, more person-centered environment. Importantly, understanding the transitional phases and having a holistic perspective will allow for a more holistic view of the person. Furthermore, information about the journey can aid in shifting the focus of health care toward those activities most valued by the patient [ 38 ]. This is a valuable and efficient contribution to the relationship between the system, medical team, and patients, as well as to providing resources dedicated to the patient’s needs at any given time, thus improving their quality of life and involving them in all decisions.

Study design and data collection

We conducted a qualitative study to explore the pathway of standard care for women with breast cancer and to develop a schematic map of their journey based on their experiences. A detailed description of the methodology is reported in the published protocol “Ascertaining breast cancer patient experiences through a journey map: A qualitative study protocol” [ 39 ].

An interview guide was created based on breast cancer literature and adapted with the collaboration of two medical oncologists, three nurses (an oncology nurse from the day hospital, a case manager nurse who liaises with the different services and is the ‘named’ point of contact for breast cancer patients for their journey throughout their treatment, and a nurse in charge of explaining postoperative care and treatment), and two psycho-oncologists. The interview covered four main areas. First, sociodemographic and medical information. Second, daily activities, family, and support network. Third, participants were asked about their overall perception of breast cancer and their coping mechanisms. Finally, physical, emotional, cognitive, spiritual, and medical aspects related to diagnosis, treatment, and side effects were probed. Additionally, patients were encouraged to express their thoughts should they want to expand on the subject.

The study was carried out at nine large hospitals located in six geographical areas of Spain. To evaluate the interview process, a pilot test was performed. Interviews were conducted using the interview guide by the principal investigator who had previous experience in qualitative research. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, all interviews were completed online and video recorded with the consent of the study participants for subsequent transcription. Relevant notes were taken during the interview to document key issues and observations.

Participant selection and recruitment

Inclusion criteria were being female, over 18 years of age, having a diagnosis of histologically-confirmed adenocarcinoma of the breast, and good mental status. To ascertain the reality of women with breast cancer, most of the patients recruited (80%) had been diagnosed in the past 5 years. Patients (20%) were added who had been diagnosed more than 5 years earlier, with the aim of improving the perspective and ascertaining their experience after 5 years.

Medical oncologists and nurses working at the centers helped identify patients who met the inclusion criteria. Participants went to the sites for follow-up between December 2019 and January 2021. Eligible women were informed of the study and invited to participate during an in-person visit by these healthcare professionals. Those who showed interest gave permission to share their contact information (e-mail or telephone number) with the principal investigator, who was the person who conducted all interviews. The principal investigator contacted these women, giving them a more detailed explanation of the study and clarifying any doubts they may have. If the woman agreed to participate, an appointment was made for a videoconference.

A total of 21 women agreed to participate voluntarily in this research. With the objective of accessing several experiences and bolstering the transferability of the findings, selection was controlled with respect to subjects’ stage of cancer, guaranteeing that there would be a proportional number of women with cancer in all stages, as well as with relapses.

Data analysis

The data underwent qualitative content analysis. To assure trustworthiness, analyses were based on the system put forth by Graneheim, and Lundman [ 40 ]. Interviews were transcribed and divided into different content areas; units of meaning were obtained and introduced into each content area; meaning codes were extracted and added; codes were categorized in terms of differences and similarities, and themes were created to link underlying meanings in the categories. All members of the research team (core team, two medical oncologists, three nurses and two psycho-oncologists) reviewed the data and triangulated the outcomes between two sources of data: qualitative data from the interview and non-modifiable information, such as sociodemographic (i.e., age, marital status, having children) and clinical (i.e., cancer stage and surgery type) data. Following this process, we reached saturation of the interview data by the time we had completed 21 interviews.

Ethical considerations

This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki, and its subsequent amendments. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of University of Barcelona (Institutional Review Board: IRB00003099) and supported by the Bioethics Group of the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology (SEOM) 2018 grant. All participants received a written informed consent form that they signed prior to commencing with the interviews and after receiving information about the study.

Patient baseline characteristics

In total, 21 women with a mean age of 47 years (range, 34 to 61) were interviewed. Most of the study population was married (66.7%), had a college education (66.7%), and had 2 or more children (42.9%). All cancer stages were represented, up to 23.8% tumor recurrence, and most of the primary cancers had been resected (95.2%) (see Table 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257680.t001

Description of the breast cancer patient journey

The women diagnosed with breast cancer describe the journey as a process tremendously affected by the different medical stages. Each stage has its own characteristics that condition the experiences, unleashing specific physical, emotional, cognitive, and social processes. Additionally, the patients perceive this entire process as pre-established journey they must undertake to save their life, with its protocols based on the type and stage of cancer.

“ People said to me , ‘What do you think ? ’ and I answered that there was nothing for me to think about because everything is done , I have to go on the journey and follow it and wait to see how it goes” (Patient 6)

Fig 1 displays the various phases of the journey that patients with breast cancer go through; nevertheless, each woman will go through some or others, depending on their type of cancer.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257680.g001

Throughout the entire patient journey.

Processes of loss and reinterpretation of the new circumstance . What stands out the most in the process these women go through during the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer is loss; specifically, the loss of health and a reinterpretation of the new circumstance and the new bodily reality. In the most extreme cases, the loss of health emerges with the fear of death that many women report at the time of diagnosis or during treatment, due to the distress generated. The loss of identity seems to be related to the evolutionary (existential) moment in which the woman is; there are patients who report feelings of disability or loss of attractiveness, or fear of not being able to get pregnant in the future, especially the youngest.

I felt a terrifying fear and thought , “You have cancer you tell yourself , you’re going to die tomorrow .” (Patient 6) I feel like after the hysterectomy , as a woman , I no longer have anything , only the physical . Sure , I look great , but I tell myself that it’s just a shell , the shell I inhabit , because as a woman , I only have one breast left . (Patient 6) At that moment , I had to make the decision that I was no longer going to be a mother . (Patient 14)

Personal change . Most of the women report that with the diagnosis of breast cancer, their life stands still and from that point forward, a different journey begins. The sole focus on this journey is the disease and its implications. During all those months, the patients stop working; they focus on their medical treatments, and reflect a lot on their current situation and on life. Most of the participants state, especially those who have already been discharged, that they know themselves better now; they take better care of themselves, and they enjoy their day-to-day and the small moments more, making the most of their time, with more initiatives and fewer trivial complaints.

Clearly , you’re not the same person you were before; I don’t think she’ll ever come back; your mindset changes completely and I have sequelae from all the treatments . (Patient 1) I re-think wasting energy on lost causes; what’s more , I’ve also learnt to say no . If I’m not in the mood to go somewhere , I just say no . (Patient 7) I take much more advantage of the present now , because you realize that things can change on any given day . (Patient 3)

Trust and appreciation for their physician . Most of the interviewees stated that they fully trusted the doctors who care for them, without question or objection to the treatments proposed. They reported that, as they go forward, they discuss the tests and treatments that are going to be performed, as well as possible side effects. Several stated that they are unaware of the stage of their cancer; similarly, most also do not know the benefits expressed in X% of the treatments. A few of the participants claimed that they did talk in detail about the different types of treatments with their oncologists, that they had sought another opinion, and one of them even reported having decided to stop chemotherapy, which was very hard for her, given her physician’s insistence that she continue.

The truth is that the oncologist didn’t say much about percentages; what she told me were the steps that I had to take; I thoroughly trusted her and she gave me a lot of peace of mind . (Patient 5) I told him , “I’m going to do whatever you tell me to . ” It never occurred to me to dispute whatever the oncologist might tell me . I was willing to do whatever was needed . (Patient 8)

Most of the women, at some point during the interview, state that they are grateful for the care they received and that, within the seriousness of their situation, there is a treatment for their condition.

I am super grateful for the treatment I’ve received and with the doctors assigned to me . (Patient 2) I’m very lucky; I’m only on my second line of treatment for metastasis and I’ve got a lot more ahead of me , but I consider myself lucky and I believe things are going very well . (Patient 20)

Role of the woman . We can see that the women adopt a role of care-givers and managers of their surroundings. They worry about the disease negatively affecting the people around them, which is why they make an effort to manage the family’s activity for when they can’t do it and they try to avoid being a physical burden or cause emotional distress to the people around them.

I was very strong ; I made everything easy for people , but making it very easy , doesn’t mean that it was easy for me , but that I made it easy for everyone . (Patient 8) I didn’t want to worry anyone because that’s just the way I am , I push forward and that’s that . (Patient 5)

Support network . In all cases, the family appears to be one of the elements that is most involved in the disease process. Within the family, the partner deserves special mention. The testimonies in this regard reveal a wide spectrum of possibilities that range from the feeling of having had great support to a lack of attention and understanding that, in many situations, causes the relationship to be strained or to end. Friends tend to appear more occasionally.

I can’t complain about my husband; he was up to the challenge , very attentive toward me and he fully understood how I was feeling ; I felt very supported . (Patient 14) We’ve had a period of a lot of arguing; I’ve had to sit down with him and tell him that life had changed for me . (Patient 18) I had a partner I had lived with for five and a half years and he told me , literally , that he looked at me like a little sister , no longer as a woman , and he left me , and that hurt me tremendously . (Patient 6)

On the other hand, many patients commented on the importance of social media, where they have met people in the same situation as them. They report feeling understood and in good company; likewise, they commented on the importance of being able to share their doubts and get to know about other experiences.

It’s a situation that only someone who has gone through can understand; you can have all the good intentions in the world , but if you haven’t gone through it , you can’t even begin to understand . (Patient 8)

Use of complementary treatments . Most patients follow conventional medical treatment. However, many resort to other disciplines that help them improve their quality-of-life, like dietary changes, getting more exercise than usual, visits to a psychologist or physical therapist, or using other integrative therapies, such as acupuncture, yoga, reiki, flowers of Bach, homeopathy, cannabis, or meditation.

I started to read a whole bunch of books to see what I could do to take care of myself in terms of nutrition and exercise ; you consider everything you can do . (Patient 5)

Diagnosis/unmasking.

This phase encompasses the time from when the woman detects some symptom or goes to a check-up until the medical diagnosis is made. For the woman, this is a time of a series of tests and results. We have observed that the procedures, especially the healthcare professionals that deal with the patients, and the timing vary, depending on the medical center where they are being cared for. Emotionally, this is one of the most complicated stages.

Emotional whirlwind . The wait to obtain test results has a huge emotional impact for the women, given that it is a time of great uncertainty and fear.

An entire month with all the anguish of finding out if you have something . (Patient 3) The worst part is waiting 15 days to find out the magnitude of the tragedy , if it’s throughout your entire body or only in your breast; you go through a brutal emotional whirlwind; the wait is horrible because there’s nothing else you can do , so that anguish that you carry inside is dreadful; it was hell for me . (Patient 10)

Additionally, the interviewees described many other emotions that included fear of death, fear of having no time, feeling of unreality, rage, anger, sadness, avoidance, denial…

The first thing I thought was that I was going to die and that I wouldn’t finish watching my children [grow up]; my father had died of lung cancer 25 years ago . (Patient 9) My only aim was to get back to normal , as if there were nothing wrong . (Patient 4) You have a lot of conflicting feelings; you wish this weren’t happening; you want to run away , but you say , “Where am I going to run to ? ” . (Patient 14)

Impact of medical communication . Several women comment that, when given the diagnosis, they dissociate because of the emotional impact and that they don’t listen to all the information that the medical professional is giving them.

I remember that she talked and talked , but I didn’t know what she was saying until she said , “Isabel , you’re going to be cured , okay ?”. (Patient 9)

During the diagnostic testing, the women are highly sensitive to the healthcare professionals’ words and gestures.

I looked at the face of the person who was doing the mammogram and that’s when I started to imagine the worst . (Patient 20) I say to them , “ But , is there a solution to this ? ” , and they say to me , “Don’t worry , I’m sure there is a solution . ” That “sure” is etched in my mind . (Patient 10)

Communication and managing their surroundings . After the diagnosis, the patients feel that they have to tell the people around them about their situation, especially those closest to them, the family. They all agree on how hard it is to share. Normally, the people it’s hardest to tell are their mother and their children. When they do, they try to put the most positive spin on it possible, in an attempt to keep them from worrying.

You no longer think only about yourself , you think , “Good grief , now I’ve got to tell my mother .” It’s hard . (Patient 16) I wanted to tell my kids the way I say things , always trying to look for the upside , and positive , although it was hard , but , anyway , in the end , it went well . When I finished , my husband told me , “You’ve convinced me that it’s no big deal .” (Patient 9) I told my son , “Son , don’t cry , your mom’s going to get over this , this is nothing .” (Patient 1)

During this period, the women contemplate how their situation will affect their surroundings and they try to organize it as much as possible.

I devoted myself to planning everything , to organizing what to do with my daughter , and to thinking about work , too , how I had left things at work . (Patient 4)

Surgery/cleaning out the cancer.

Uncertainty and fear . The participants express that before going into surgery, they are told about the kind of procedure that will be done, but that, depending on what they find and the analysis, it may change. In light of this, they exhibit an enormous feeling of uncertainty and fear. In addition, many voice concern about how the surgery will go.

They tell you conservative surgery , but if we open up and see something we didn’t see on the tests , then everything could change . (Patient 10) Aside from the anesthesia , that I’m terrified of , you spend several hours in surgery and you don’t really know how things will go; when they clean it out , they analyze it , and you go into the operating room and you don’t know what can happen . (Patient 9)

Feeling of loss . Considering that the breast is associated with an intimate, feminine part [of their body], many women experience the operation as a loss. This loss is more acute if the operation is a mastectomy and there is no reconstruction at the same time. The loss also involves a loss of identity, compounded by the side effects of chemotherapy, such as hair loss. The interviewees who had undergone mastectomy say that following surgery, when the bandaging is removed and the scar is revealed, is one of the most critical moments, which is why they express difficulty in managing it and appreciate the caring assistance from the professionals.

It is identification with yourself , you know , it’s what you’ve seen in the mirror , what you think you’re like and , suddenly , you’re no longer like that; there’s an incredible personal crisis because you no longer recognize what you’re seeing . (Patient 11) I closed my eyes and I removed the bandaging and I didn’t dare look … with my eyes , I imagined the worst . (Patient 12)

Acceptance or demand for more aggressive intervention . The patients perceive the surgery as essential to recovering their health, which is why the process is widely accepted. Some patients who demand a more invasive intervention, normally a bilateral mastectomy, do so because that way, they feel safer with respect to a possible relapse, as well as more comfortable esthetically.

If they have to remove my breast , let them take it; what I want is to get better . (Patient 16) They say that I am in full remission , so they only removed the lump , but at first , I said that I wanted my whole [breast] removed ; then they assessed how to do it . (Patient 13) They told me that I had a genetic mutation and more possibilities of developing breast cancer and , since I felt such rejection toward my remaining breast , I decided to get rid of that one , too . (Patient 20)

Chemotherapy/loss of identity.

The chemotherapy phase is one of the phases that affects the women’s lives the most, because of its physical impact and how long it lasts. No differences have been found in how they experience chemotherapy depending on whether it was neoadjuvant or adjuvant.

Negative impact of side effects . Chemotherapy is associated with many side effects that vary from one woman to another. Many indicate that they have suffered physical discomfort, such as fatigue, dysgeusia, pain, nausea and vomiting, mucositis, diarrhea, etc.

One day when I didn’t want to go to bed , I went to bed crying because I had the feeling that I wasn’t going to wake up . That day it was because I felt awful . (Patient 1)

Furthermore, all of the women suffer hair loss, which is one of the most-feared effects. Likewise, their body hair also falls out, especially on their face, and their weight fluctuates. All of these changes lead to a loss of identity that is experienced as taking away from their femininity. It must be remembered that oftentimes, chemotherapy is administered after surgery, further exacerbating this physical change. On top of all that, several women comment having to decide at the beginning of treatment whether to freeze their eggs or not; at that moment, many of them forfeit the possibility of becoming a mother or of becoming a mother again, which also adds to this loss of femininity.

Losing my hair was hard , but when it grew out again , I had an identity crisis . I didn’t recognize myself; people said I was really pretty like that , with my hair so short . I looked at myself in the mirror and I said that I’m not that woman , I can see that that woman is pretty , but it’s just that I don’t recognize myself . That’s not me or , it was like , I looked at myself and I didn’t recognize myself . That’s when I suffered a serious identity crisis , psychologically serious , but also serious because I sobbed because I looked at myself , but it wasn’t me . (Patient 6) Where’s that sexy lady , where is she ?, because you don’t feel good . I didn’t like myself at all . I was several sizes larger and I looked at myself and said , “What a monster . ” I didn’t feel good about myself . (Patient 1)

Many patients say that chemotherapy decreases their libido and dries up their mucous membranes, which is why they prefer not to have sex. For those who live as a couple, this situation can strain the relationship.

Sexually , I just didn’t feel like it , I wasn’t in the mood; not only did I not feel like it , my mucous membranes were dry and , what’s smore , I just couldn’t , I couldn’t , I felt bad for my husband , but he said , “Don’t worry .” (Patient 16)

Finally, some interviewees expressed a feeling of being poisoned by the treatment. These women tend to be highly focused on taking care of their body and have a very natural attitude toward life.

I had to really work my awareness that I was poisoning myself; at night I was at home and I thought that all that red liquid was circulating through my veins … I think I even had nightmares . (Patient 4)

Balance between caring for oneself and caring for others . The patients feel that it is time to take care of themselves, so they prioritize resting when they need it. Moreover, they worry about getting a haircut and, most of the times, they look for turbans and wigs. Some also learn how to put on make-up, which they rate as being very positive. On the other hand, those who have children or another person in their care, try to take care of them as much as they are able.

Around 11 : 00 , I no longer felt good , so I’d go to the armchair to rest and it’s like I had an angel , because I’d wake up a minute before I had to set the table and get lunch for my son who would be coming home from school . (Patient 1) While I was getting chemo , I went with the gadget and I told myself , “I’m going to teach you to apply make-up; for instance , your eyelashes are going to fall out . Make a line like this ” and at that moment when you look in the mirror , and we look like Fester in the Addams family . (Patient 13)

Vulnerability . The women experience great uncertainty and feelings of vulnerability the first times they receive chemotherapy, since they don’t know what side effects they will suffer.

With chemo , I started with a lot of fear and , later on , I became familiar with it little by little until the time comes when you go to the hospital like someone who’s going to pick up a bit of paper . (Patient 9)

In addition, those participants who join a social network or who are more closely tied to the hospital setting, know about the relapses and deaths of people around them diagnosed with breast cancer, which makes them feel highly vulnerable.

There are some people who leave the group because … it’s not like there are a lot of relapses and , geez , I think that it messes with your head . (Patient 13) We were almost always the same people at chemotherapy ; there was one guy who was really yellow who looked terrible and , there was one time when we stopped seeing him and another lady asked and the nurse said that he had died . (Patient 15)

At the same time, given the physical changes, especially those that have to do with body hair, many women feel observed when they leave home.

If I have to go out and take off my scarf because I’m hot or go straight out without any scarf on my head and whoever wants to look… let them ; I think that it’s up to us , the patients , to normalize the situation; unfortunately , there are more and more cases . (Patient 9)

Telling the kids . Since when the chemotherapy stage is going to entail many physical changes, the women look for ways to talk to their children about the treatment. Most of them comment that it is a complicated situation and all of them try to talk to their children in such a way as to protect them as much as possible.

I asked the nurse for help before I started chemotherapy to see if she had any pointers about how to talk about this with the kids and she recommended a story , but when I saw it , I didn’t like it … so , in the end , I decided to do it off the cuff . (Patient 10)

Radiotherapy/transition to normality.

The “last” treatment . When the patient reaches radiotherapy, normally, they have already spent several months undergoing physically aggressive medical procedures, which is why they feel exhausted. There is a physical exhaustion resulting from the previous treatments and made worse by the radiation therapy. Furthermore, many women also report feeling emotionally drained by the entire process. However, this is generally accompanied by joy and relief because they feel that they are in the final stage of treatment.

Emotionally , it’s a marathon that has to end up at some point . (Patient 10) For me , radiotherapy was like a lull in the battle , with a winning mind-set . (Patient 4)

Comparison with chemotherapy . There is a widespread perception that radiotherapy has fewer side effects than chemotherapy, although later, when they receive it, several patients suffer discomfort, above all fatigue and dizziness. Several report that at this point, they are mentally worn out and just want to be done with the process, which is why they have less information than about chemotherapy.

I feel like radiotherapy is unknown , that you think it’s more “light ” and it turns out not to be so light . (Patient 13)

Follow-up care/the “new” day-to-day.

Difficulty in getting back to normal . Once the patients are discharged, many feel that they need some time to recover, that it will be slow, in order to restore a more normalized pace of life. They are still working on their emotional and personal process.

When they tell you that you have cancer , they make it very clear : you have a goal; you have some months of chemo , some months of radio , and when you finish , you say , “And now , what do I do ?”. I say that because now I have to get back to my normal life , but I don’t feel normal . I still don’t feel cured , I’m not 100% . And you’re glad you’ve that you’ve finished it all and you’re alive , but at the same time , you say , “Gosh… this is very odd . ” It was a very strange feeling . (Patient 8)

Most patients report that their quality-of-life has diminished, due to the sequelae from the treatments. Lymphedema is one of the sequelae they name most often, although they also mention other symptoms, like digestive upset, weight issues, eye problems, scar pain, etc. The women who are on hormone therapy also suffer side effects, such as joint and muscle pain.

I have lymphedema and , although I have good mobility , I’m a little bit weak; when I go out for dinner , I generally order fish , because I can’t always cut meat well . (Patient 6)

Several interviewees also express difficulty in their affective-sexual relations. Many of them feel insecure because of all the physical changes; others have sequelae that hinder their relations, and still others are suffering symptoms of early menopause. This can cause problems in the couple and for those who don’t have a partner, suffer many complications when it comes to meeting other people.

I haven’t had sex with my husband for 2 years because , it’s also really complicated to get over; I’ve gone for pelvic physical therapy; I’ve used gels , but nothing works . (Patient 8) It’s taken me many months for me to have a relationship again; it’s been really hard because , even though everyone told me that I looked fine , I didn’t feel fine . My breast cancer had taken away all my attributes as a woman . (Patient 6)

Some women also experience difficulties when it comes to returning to work. Several state that they had been fired when they went back. They also report that when interviewing for a job, it’s complicated for them because they have to explain what happened and they mention the schedule of doctor’s visits that they have. Other women comment that they’ve been given early retirement or disability.

You go to the interview and if you tell them that you’ve had the disease , they look at you like you’re a weirdo . (Patient 13)

Breast reconstruction . How reconstruction is experienced, as well as its timing, are highly contingent upon they type of reconstruction. Each one has its pros and cons, but the opinions collected with respect to the type of reconstruction have been positive.

Although it took 18 months for the entire process to be over , I’m delighted with reconstruction with the expander . (Patient 16)

Some patients state that after the whole process, which has been long and complicated, they prefer not to undergo reconstruction immediately. In these cases, they report having felt a subtle pressure from the outside to undergo reconstruction.

Every time I went for my check-ups , they said , “You’re the only one left [who hasn’t undergone reconstruction]” and in the end , the truth is that I’m really happy because I think I look pretty . (Patient 12)

Check-ups and fear of relapse . Check-ups are one of the times that generate most worry and insecurity. The women remark that, starting a few days before and until they receive the results of the follow-up studies, they are more anxious about the possibility of relapse.

At every check-up my legs start shaking again and my stomach is in knots, although at my last one, everything turned out okay and I’m thrilled. (Patient 6) During the first stage , I did everything I had to do and I got over it , but it’s a lottery . You can do whatever you want , but it’s the luck of the draw and when you start going for check-ups , it’s like going to play Russian roulette . (Patient 8)

Maintenance hormone therapy . Hormone therapy is understood differently depending on age and on the major decision of whether or not to be a mother or to have another child. If the woman does not want to have more children, the treatment is accepted better. The patients who take it also report effects derived from menopause, for instance, joint pain or dry mucous membranes.

I did notice joint pain , but since I exercised , [I felt it] much less than my fellow women , although , for instance , when it comes to getting up from a chair , you get up like an old lady . (Patient 10)

Position of support . Several patients mention that, after discharge, they stay active on social media, they volunteer when they find out about someone or to participate in activities related to breast cancer, with the aim of being able to help other people who are in this situation.

It’s really good to meet other people who are going through the same thing , so , now that I’ve finished , I like it and I always help whenever I can , because I can share what was good for me . (Patient 13)

Relapse/starting over.

Emotional impact . The diagnosis of a relapse is experienced much the same as the initial diagnosis. All of the women report fear, although they also state that they are more familiar with the processes. Other emotions emerge, such as why me, blame, disbelief, etc.