Your Account

Manage your account, subscriptions and profile.

MyKomen Health

ShareForCures

In Your Community

In Your Community

View resources and events in your local community.

Change your location:

Susan G. Komen®

One moment can change everything.

Susan G. Komen Blog

Stories about breast cancer that can inspire and inform.

Blog | Newsroom

My Cancer Journey

My Breast Cancer Journey

Hanna-Marie lives in Houston, Texas. She was diagnosed with breast cancer in December 2020. This is her story in her words.

I was diagnosed with a type of breast cancer called triple positive invasive ductal carcinoma on Dec. 15, 2020. I had no family history.

I found a mass in mid-September 2020 that felt like a pencil eraser. During this time, I was having horrible nausea and pelvic pain weeks after my cycle and ovulation period. This was out of the norm for me, even during my cycle. I was one of the lucky ones with no cramps or nausea.

I went to the OBGYN in late September to discuss the nausea and pelvic pain and totally forgot to discuss the mass. I received a pelvic ultrasound and was told there weren’t any abnormalities. My well women’s exam was due in late October, so I waited until then to alert my doctor about the mass. Her saying is, “If you feel something, we without a doubt do a mammogram.” I’m 35 years old, so I had never received a mammogram before.

Due to work schedule and scheduling with the imaging center, I didn’t get the mammogram until November 2020. I received a mammogram and a breast ultrasound. Three masses were discovered that required a biopsy, which I had in early December. A week later the biopsy results revealed:

- Estrogen receptor-positive

- Progesterone receptor-positive

- Her2-positive

The best advice I can give to someone newly diagnosed is to:

- Take it one step at a time. It can be overwhelming to hear you need chemotherapy, surgery, radiation therapy. After treatment, there’s hormone therapy for years. Don’t think about the next step until it’s time.

- Take time to review your health insurance benefits—you would be surprised at what things can be covered with a cancer diagnosis. For instance, acupuncture wasn’t covered with my plan unless there was proof of a chronic illness such as cancer.

- Trust your gut and don’t be forced into something that doesn’t feel right for you.

- Advocate for yourself—no one else will take care of you like you can. Speak out of something isn’t right and remember: closed mouths don’t get fed.

- Don’t be scared to ask questions!

As of August 2021, I am Cancer Free!

Statements and opinions expressed are that of the individual and do not express the views or opinions of Susan G. Komen. This information is being provided for educational purposes only and is not to be construed as medical advice. Persons with breast cancer should consult their healthcare provider with specific questions or concerns about their treatment.

Related Stories

Human Answers to Your Cancer Questions

Welcome to The Patient Story, where you can find hope, guidance, and a supportive community. Explore insights on navigating life after a cancer diagnosis, discover promising treatments, and connect with people who truly understand what you're experiencing. Remember, you're not alone – we're here to help you through this journey.

Welcome to The Patient Story, where you can find hope, guidance, and a supportive community. Explore real patient symptoms, tests, treatments and how to manage treatment side effects.

Remember, you’re not alone – we’re here to help you through this journey.

Ashley’s Stage 4 Rare Adrenal Cancer Story

Samantha’s Cervical Cancer Story

Tracy’s Stage 2B Colorectal Cancer Story

Joe’s Rare Desmoplastic Small Round Cell Tumors (DSRCT) Story

You are not alone.

This time in your life can be overwhelming. Allow us to do some of the work for you. Sign up for our e-newsletter to find out what the cancer journey is really like – from the people who have lived it.

Navigating Your Life with Cancer

Not sure where to begin? We can help. Learn about first symptoms, treatment decisions, questions to ask your doctor, and navigating life with cancer.

Patient Events - Virtual & In-Person

Get your cancer questions answered in real time by leading experts and patients. Explore upcoming and past patient live discussions. Plus, easily sort by cancer type.

Insights by Cancer Type

Detailed stories direct from cancer patients and survivors to help anyone facing a cancer diagnosis of their own, tailored by cancer type.

Share Your Story

Inspire others and join our community today.

Share your cancer journey and make a difference. Whether you’re a cancer survivor, patient, caregiver, or advocate, your story is important and matters. Sharing your story with others can inspire hope, educate and create a lasting impact.

The Patient Story Partners

Join our community.

Get the latest cancer stories, helpful resources, and personalized advice directly to your inbox.

Copyright 2024 © The Patient Story

For cancer patients and caregivers.

Quick Links

Additional Links

Answers. Strength. Confidence. TM

Be ready to take on cancer before, during, and after treatment

Getting screened to help find cancer

Knowing which screenings you need and when to get them can be helpful in finding cancer earlier, before it has spread. See cancer screening recommendations by age

Preparing for cancer surgery

Your doctor may recommend surgery to help treat your cancer, as well as additional treatment before or after surgery. Learn about surgery and how it may fit into your treatment plan

Building your cancer care team

Understand the types of health care providers who may be able to help you through your cancer and treatment journey. Get familiar with what different team members do

Understand your type of cancer

A greater understanding of the different types of common cancers can help you or someone you love manage the journey.

Life with cancer

Sharing your cancer diagnosis.

Cancer is hard to deal with all alone. You have control over if, when, and how much you share about your diagnosis.

Preparing for your first cancer treatment

From Harvard Health Publishing

You can take the edge off your first day of treatment by focusing on stress-relieving techniques and being as comfortable as possible.

How to manage limited energy

Fatigue can be expected with some treatments, but it could also be a serious side effect of your treatment. The first thing you should do is talk with your doctor when you experience fatigue.

Finding a support group

Even if your family and friends are hugely empathetic, a cancer-specific support group may give you even more freedom to discuss your concerns.

Questions to ask your doctor

Use these questions to help prepare for doctor visits throughout your journey.

Sign up for updates

Be the first to know when new information and articles become available.

You are leaving Understand Cancer Together

The link you selected will take you to a site outside of Merck.

Merck does not review or control the content of any non-Merck site. Merck does not endorse and is not responsible for the accuracy, content, practices, or standards of any non-Merck site.

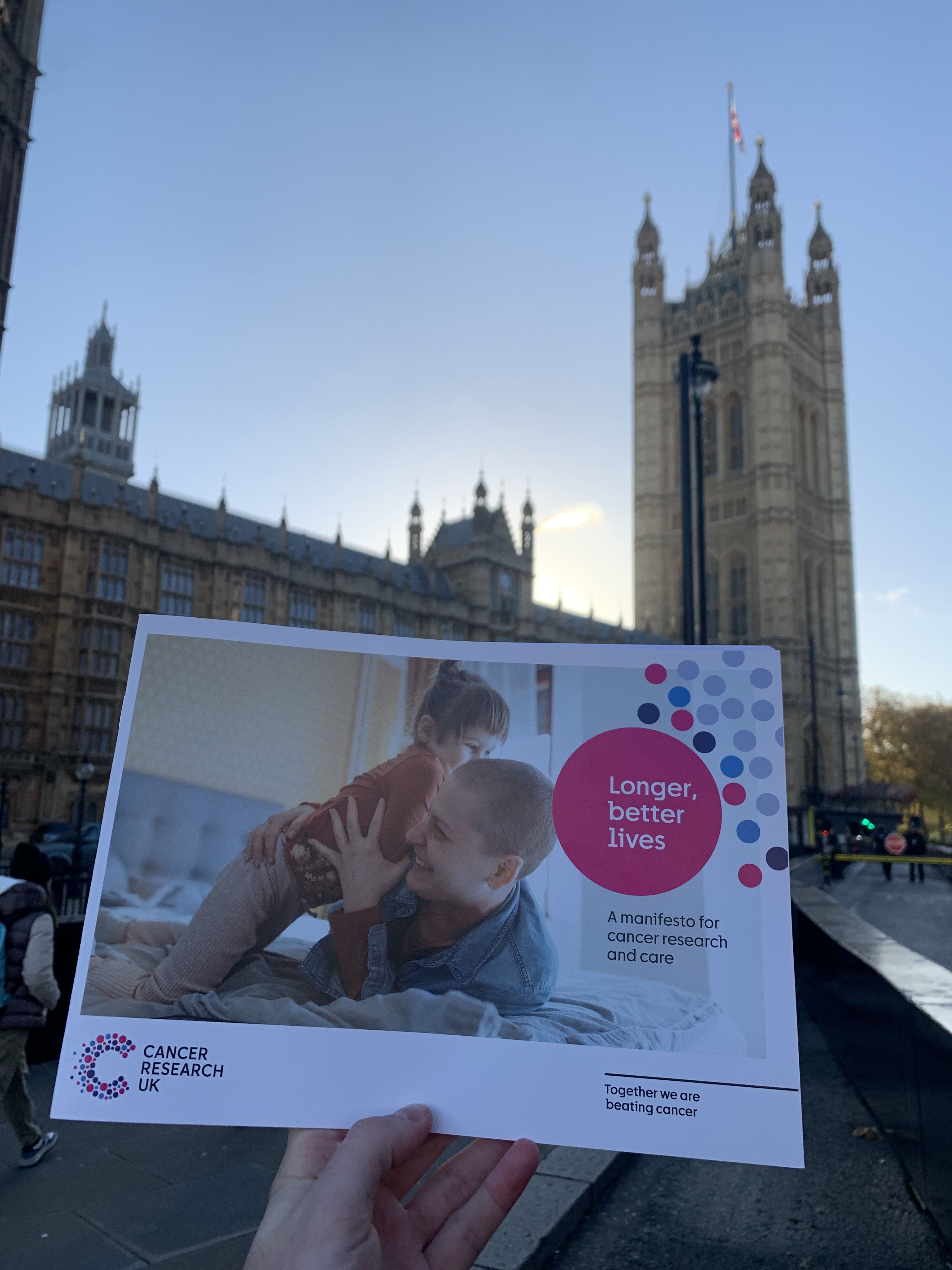

Together we are beating cancer

- Cancer types

- Breast cancer

- Bowel cancer

- Lung cancer

- Prostate cancer

- Cancers in general

- Clinical trials

- Causes of cancer

- Coping with cancer

- Managing symptoms and side effects

- Mental health and cancer

- Money and travel

- Death and dying

- Cancer Chat forum

- Health Professionals

- Cancer Statistics

- Cancer Screening

- Learning and Support

- NICE suspected cancer referral guidelines

- Make a donation

- By cancer type

- Leave a legacy gift

- Donate in Memory

- Find an event

- Race for Life

- Charity runs

- Charity walks

- Search events

- Relay for Life

- Volunteer in our shops

- Help at an event

- Help us raise money

- Campaign for us

- Do your own fundraising

- Fundraising ideas

- Get a fundraising pack

- Return fundraising money

- Fundraise by cancer type

- Set up a Cancer Research UK Giving Page

- Find a shop or superstore

- Become a partner

- Cancer Research UK for Children & Young People

- Our Play Your Part campaign

- Brain tumours

- Skin cancer

- All cancer types

- By cancer topic

- New treatments

- Cancer biology

- Cancer drugs

- All cancer subjects

- All locations

- By Researcher

- Professor Duncan Baird

- Professor Fran Balkwill

- Professor Andrew Biankin

- See all researchers

- Our achievements timeline

- Our research strategy

- Involving animals in research

- Research opportunities

- For discovery researchers

- For clinical researchers

- For population researchers

- In drug discovery & development

- In early detection & diagnosis

- For students & postdocs

- Our funding schemes

- Career Development Fellowship

- Discovery Programme Awards

- Clinical Trial Award

- Biology to Prevention Award

- View all schemes and deadlines

- Applying for funding

- Start your application online

- How to make a successful applicant

- Funding committees

- Successful applicant case studies

- How we deliver research

- Our research infrastructure

- Events and conferences

- Our research partnerships

- Facts & figures about our funding

- Develop your research career

- Recently funded awards

- Manage your research grant

- Notify us of new publications

- Find a shop

- Volunteer in a shop

- Donate goods to a shop

- Our superstores

- Shop online

- Wedding favours

- Cancer Care

- Flower Shop

- Our eBay store

- Shoes and boots

- Bags and purses

- We beat cancer

- We fundraise

- We develop policy

- Our global role

- Our organisation

- Our strategy

- Our Trustees

- CEO and Executive Board

- How we spend your money

- Early careers

- Your development

Cancer News

- For Researchers

- For Supporters

- Press office

- Publications

- Update your contact preferences

- About cancer

- Get involved

- Our research

- Funding for researchers

The latest news, analysis and opinion from Cancer Research UK

- Science & Technology

- Health & Medicine

- Personal Stories

- Policy & Insight

- Charity News

A journey through the cancer pathway

A road to longer, better lives

By Amy Warnock

Nearly 1 in 2 of us will get cancer in our lifetimes.

And that statistic applies to Alex too - our fictional character in this story.

Alex is 47 years old and lives in Sheffield. Alex loves playing tennis, catching up on the latest tv series, and meeting up with friends for a drink and a board game at their local pub.

Like many of us, Alex has had family members affected by cancer and knows first-hand how cancer can impact on someone’s life.

While we have made huge progress on cancer in the past 50 years, we still have a long way to go.

At the moment, the UK lags behind other comparable countries when it comes to cancer survival. And the challenge is only growing.

So let’s follow Alex’s journey through their cancer diagnosis and treatment and look at some of the barriers they encounter along the way.

But while these barriers might exist for now, they can be overcome. So we’ll also look at how government action could transform the cancer pathway and lead to more people living longer, better lives.

Prioritising prevention

As with everyone, Alex’s cancer journey actually starts before their cancer diagnosis. It starts with how Alex goes about living their everyday life.

And that’s because around 4 in 10 UK cancers are preventable.

So, if we can prevent cancers from developing in the first place, we can avoid the need to begin a journey on the cancer pathway.

Image source: Shutterstock/Markus Mainka

The picture now

Let’s take lung cancer as an example. It’s the third most common cancer in the UK, and every year around 49,200 people are diagnosed with the disease.

The majority of lung cancer cases are caused by smoking, which means they are preventable.

And it’s not just lung cancer. Smoking causes at least 15 types of cancer, as well as numerous other health conditions. Around 125,000 people in the UK are killed by tobacco each year - this includes smoking, second-hand smoke and chewing tobacco.

Smoking is also the biggest driver of the difference in life expectancy between the least and most affluent populations in the UK.

Alex has smoked since the age of 17, and like most people who smoke they want to give up. But because of the addictive nicotine in cigarettes, Alex has struggled.

But it’s not just smoking. Obesity and overweight is the second biggest cause of cancer in the UK and is linked to 13 types of cancer. Obesity and overweight prevalence in the UK is increasing, affecting more than 6 in 10 adults.

Drinking alcohol also increases cancer risk and the UK Chief Medical Officer's drinking guidelines advise against regularly exceeding more than 14 units of alcohol spread over a week. But there is no completely safe level of drinking, so the less you drink the better for your health.

The good news is that we can do something about these risk factors. And if we want to reduce the burden of cancer in the UK, that begins with trying to prevent it.

What can change

Put simply. if we can prevent more cancers we can save more lives.

And to do this we need strong government action.

Tackling smoking alone, to ensure that England meets its Smokefree target (that’s 5% or less of the adult population smoking) across all socio-economic groups, would prevent around 26,600 cancer cases by 2040.

And fortunately we could already be on our way to making this a reality. Recently, the UK Government announced that it will introduce legislation to raise the age of sale for tobacco , ensuring no one currently aged 14 or under can ever be legally sold cigarettes or other tobacco products. But we’re not done yet, we need to see this legislation passed, and adequate funding for services to help people stop smoking.

It’s changes like this that could prevent people like Alex ever taking up smoking in the first place, and maybe also prevent their cancer.

But this alone won’t be enough. To prevent even more cancer cases, we need to see more measures introduced to reduce the prevalence of smoking, overweight and obesity, and drinking alcohol above recommended limits in the UK.

Image captions

Image source: Shutterstock/Variety beauty background

Optimising screening

If we can’t prevent cancer, the next best thing is diagnosing it early.

That’s because by diagnosing cancers earlier we can ensure that people have more treatment options and the best chance of survival.

Image source: Shutterstock/Anamaria Meija

The UK has been focusing on early diagnosis for some time, and the NHS have a target of diagnosing 75% of cancer patients early (at stage 1 or 2) by 2028, but it is currently not on track to achieve this.

As it stands, far too many cancers are still diagnosed at stage 4, when there are limited treatment options and prognosis is often poor.

Around 1 in 5 cancer cases in England are diagnosed through emergency routes, which is associated with worse outcomes and worse patient experience. This needs to change.

A key way in which we can diagnose cancers earlier is through screening programmes , where people without symptoms are tested for early signs of cancer. The UK currently has three cancer screening programmes, for bowel, breast and cervical cancer.

But at present only 6% of cancers are diagnosed through screening, so we need to optimise and expand on these programmes to ensure that the screening programmes are working as hard as they can to help save lives.

Image source: Shutterstock/Xdbzxy

We know there isn’t a silver bullet to achieving earlier diagnosis across all cancer types. But there is a big potential for innovation in cancer screening.

The UK breast, cervical and bowel screening programmes save over 5,000 lives every year. But if we increase the uptake of these programmes across England to around 80%, we estimate that we can diagnose an extra 4,000 cases of cancer per year.

And there are also exciting new developments on the horizon.

In June this year, the UK Government announced the roll out of a new targeted lung cancer screening programme for people in England aged 55-74 who either smoke or used to smoke.

By delivering this national lung cancer screening programme we estimate that, with a 50% take up, around 1,900 lives could be saved in the UK each year.

Having smoked for a long time, a screening programme like this could have had a big impact for Alex, as it could have led to their cancer being diagnosed earlier, when there are more treatment options available.

The UK Government now need to ensure that the lung cancer screening programme is quickly implemented across England, and relevant ministers in the devolved nations should also commit to rolling out lung screening in their countries as quickly as possible.

Image credit: Rhoda Baer/National Cancer Institute

Waiting for a diagnosis

Lung cancer screening wasn’t available for Alex yet, so instead their journey to receiving a diagnosis starts when they notice some changes.

Alex first suspects that something isn’t quite right when they notice a new cough that won’t go away. So Alex goes to their GP, who gives them an urgent referral for a chest X ray.

After the X ray, Alex is referred for further tests.

And this is where we run into one of the biggest hurdles on the pathway. Cancer waiting times.

Image credit: National Cancer Institute

Getting an urgent suspected cancer referral is an incredibly stressful time, both for Alex, and their friends and family. So it should be a priority to make sure that this experience is as quick as possible.

But at the moment this isn’t happening. Performance related to cancer waiting times are at a near all-time low.

NHS England has set cancer waiting times targets , but over the past few years, these have consistently been missed.

In England, 85% of patients should start their treatment within 62 days of an urgent cancer referral. But the 62-day standard has been missed since 2015, meaning over 141,000 patients waited longer to start treatment than if the target had been met consistently.

In 2021, the new Faster Diagnosis Standard (FDS) was introduced in England, which stipulates that patients should have their cancer ruled out or receive a diagnosis within 28 days. Although the implemented target of 75% is well below the original target of 95%, this target has still not been met since its introduction.

So what can we do to make sure that people like Alex are diagnosed and treated as quickly as possible?

The main problem facing the NHS when it comes to cancer waiting times is resource, particularly when it comes to diagnosing cancer.

Fixing the cancer workforce isn’t easy, but it’s doable.

The UK Government made a good start this year by publishing their Long-Term Workforce Plan . But they need to build on this plan and commit funding to ensure that it delivers the cancer workforce that the country needs.

Importantly, as well as addressing staff and resource shortages, action needs to be taken to improve NHS workforce retention. There are proven interventions to boost retention, including access to training and professional development opportunities, flexible working and wellbeing support. Using interventions such as these, the UK Government need to fully commit to turning the tide on the numbers of experienced staff leaving the workforce.

If we can improve NHS resource and retention, and begin to meet cancer wait time targets, this could have a huge impact on patients.

By meeting the FDS target at 95%, rather than the current target of 75%, we estimate that around 49,000 extra people per month could receive a cancer diagnosis or have cancer ruled out within the proposed 28-day FDS window. Not only does that mean that cancers can be treated faster, it means less time spent worrying for people and their families.

But it’s not just cancer waits that can be fixed. With new challenges on the horizon, such as an ageing population and more complex treatments, by addressing NHS staffing shortfalls across the cancer workforce, the government can ensure that the UK have a workforce fit for the future of cancer care.

Image source: Shutterstock/Altrendo Images

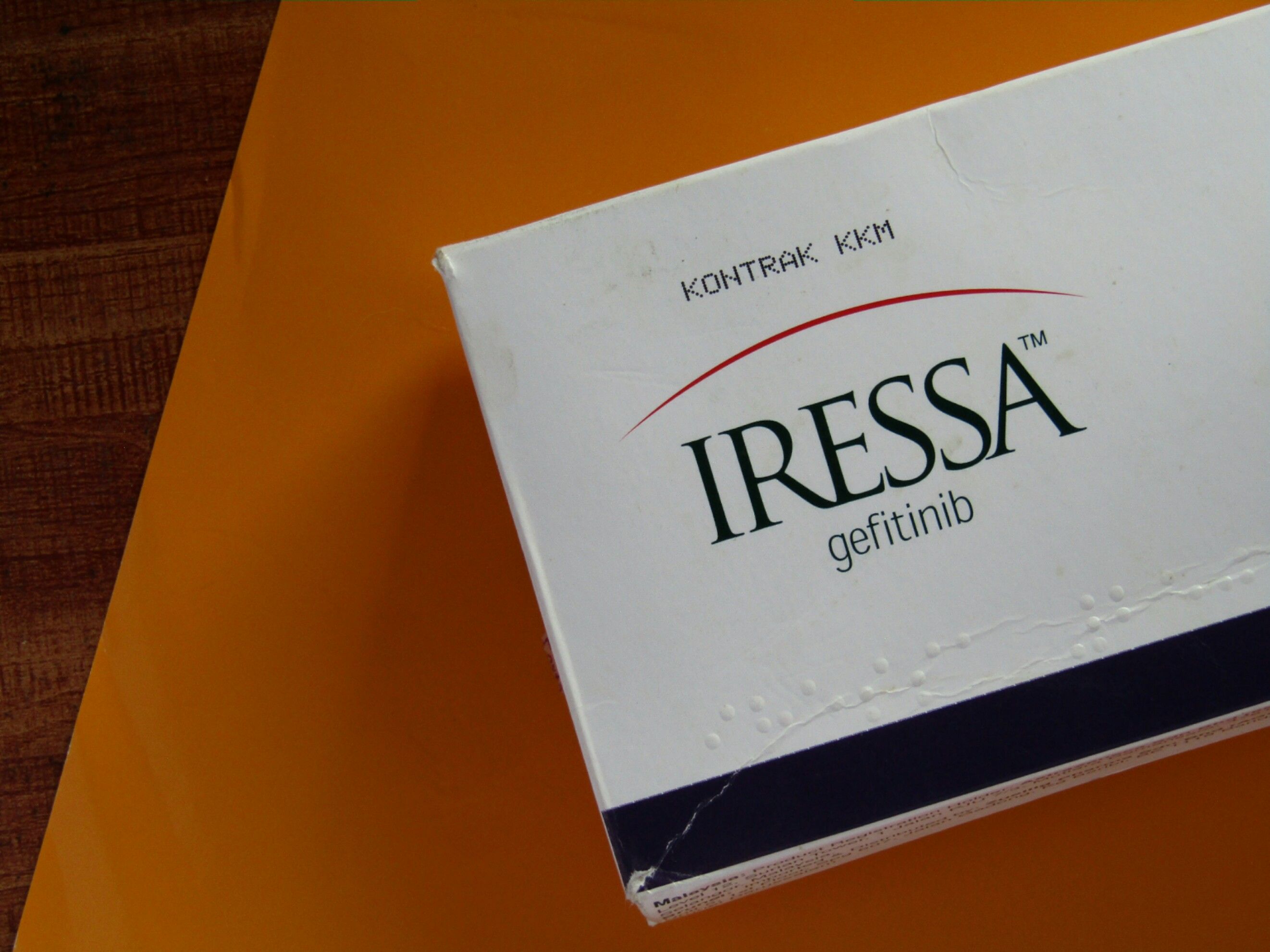

Innovating new treatments

Because of staff shortages, Alex has had to wait longer than 28 days to receive a diagnosis of lung cancer. And now they are about to begin treatment.

Alex’s treatment plan involves treatment with gefitinib. This is because Alex’s cancer has a mutation in a gene called EGFR, which is involved in helping cells grow and divide.

Gefitinib can specifically target and block EGFR activity in cancer cells

Targeted cancer treatments, such as gefitinib, have made a huge difference to people with cancer over the last 50 years. They work by targeting specific differences between cancer cells and healthy cells which help the cancer to survive and grow. This means they’re less likely to damage healthy tissue.

But the journey of developing new treatments and getting them to patients is a long one.

Image source: Shutterstock/Syazwani Pardi

The path to new treatments begins with a strong research workforce. But there are concerns over the sustainability of the biomedical research funding landscape over the next decade.

With current government levels of funding and charity income remaining static, we estimate there will be a shortfall of between £1-2bn in cancer research investment over the next decade.

But it’s not just a problem of research funding. We also need to tackle system-wide issues to ensure that research careers are attractive and accessible for everyone, remove the barriers that may stop international talent coming to the UK to do their research, and build a diverse research community.

We’re also facing barriers when it comes to translation – getting new discoveries from the lab to a place where they can benefit patients. All stages of the UK translation pipeline, from the early stages of clinical research to test safety and effectiveness through to adoption and implementation, need to be strengthened to ensure that patients can see the impact of new tests and treatments.

What can change

Of all publicly funded cancer research in the UK, around 38% comes from the government and around 62% comes from charities.

The US Government funds over 5 times more cancer research per capita than the UK Government...

...and the Norwegian Government funds over 2.5 times more.

The government needs to commit to making research and development (R&D) spending a priority.

The UK can remain at the forefront of cancer research, but it will take sustained, long-term investment across the research sector.

Investment in research not only has huge benefits for patients, but also for our economy. In 2020/21 there was £1.8bn invested into cancer research. This generated more than £5bn of economic impact .

As well as committing to prioritising funding, the government also need to ensure that barriers to cross-border research are minimised, as well as reducing potential barriers, such as high upfront visa costs, to encourage an international and diverse research workforce in the UK. Collaboration across the globe is key to solving cancers biggest problems.

The government also needs to facilitate translation in the UK, streamlining the process of bringing innovations to the health system and encouraging investment to fund the early stages of translation.

With a world-leading research sector, and a streamlined translation process, we can ensure that we continue to make groundbreaking discoveries and develop new cancer treatments for patients just like Alex.

Image source: Shutterstock/Nico El Nino

Leading on cancer

Thanks to getfitinib, Alex is able to live a longer, better life. But that’s not the case for everyone with cancer.

As we can see from Alex’s journey, the cancer pathway for a patient can be long, complex and fraught with obstacles. These obstacles will vary widely depending on the patient, but importantly many of them are fixable.

Fixing them won’t be easy, but it is possible. Cancer survival in the UK has doubled over the last 50 years, and with the right leadership we can make sure that the next 50 years are just as impactful.

The upcoming general election needs to be a turning point for people affected by cancer.

We need to see strong leadership on cancer in the UK, to ensure a long-term focus on cancer. This approach needs to bring together discovery, translation, cancer prevention, detection, diagnosis and treatment, health system investment and reform, to ensure that more of us are able to live longer, better lives.

And that’s why we’ve launching Longer, better lives: A manifesto for cancer research and care . Our manifesto outlines the steps the next UK Government must take to make transforming cancer outcomes a reality. And if you agree, you can join us in telling party leaders to back our calls for longer, better lives.

- The Journey

Patients, caregivers and loved ones rely on each other on the path to wellness. The Journey is a blog that addresses the unique hurdles each person faces.

- For Patients

- For Caregivers

- Questions to Ask My Doctor

- 30 Stories in 30 Days™

Read cancer survivors’ stories. Get great advice and inspiration from others on a similar journey.

- Share Your Story

- Just for Kids

Join Hank the Monkey with his friends as they learn about cancer and how they cope with it.

- For Parents

- For Kids & Teens

Recent Posts

- Advice for Patients

- Oral Cancer Awareness

- Thyroid Cancer

- Post Treatment

- Stress Management

- Low-iodine Diet

- Advice for Parents

- Oral Cancer

- After Surgery

- Anxiety & Fear

- Thyroid Cancer Awareness

A curated collection of instructive books.

Download a free cookbook.

Access guides on cancer diagnostics & treatments.

Easily search and match to clinical trials.

Get the definition of cancer-related terms.

Video content with easy-to-digest information.

Browse a list of devices for patients undergoing cancer treatment.

Smartphone apps, online forums & advocacy groups.

Interact with other people who share your journey.

Download the thyroid fact sheet.

Danielle’s Story (Update)

Category: the journey.

Patients and caregivers rely on each other on the path to wellness. The Journey is a blog that addresses the unique hurdles people face on their cancer journey.

How to Decode Your Thyroid Function Tests Now

Is your thyroid healthy? Find out with our complete guide to understanding T3, T4, and TSH tests. Learn more so you can decode your thyroid results today! Continue reading How to Decode Your Thyroid Function Tests Now

- Post date June 6, 2024

- Tags Advice for Patients , Cancer Testing , Diagnosis , Featured , Thyroid Cancer

Your Post-Surgery Guide to a Soft Food or Liquid Diet

Struggling after surgery? Ease your post-surgery recovery with our soft food guide. Discover great diet tips and learn some simple, soothing meal recipes today! Continue reading Your Post-Surgery Guide to a Soft Food or Liquid Diet

- Post date May 23, 2024

- Tags Cancer Recovery , Featured , Post Treatment , Recipes

How to Start a Gratitude Journal as a Healing Exercise

Cancer survivors can cultivate this secret weapon for mental and physical well-being. Learn how to start your gratitude journal now and transform your outlook. Continue reading How to Start a Gratitude Journal as a Healing Exercise

- Post date May 9, 2024

- Tags Advice for Caregivers , Featured , Resources

Spotlight on Cancer Research Month This May

Learn about the research and collaboration driving cancer advancements. Read survivor stories and see how teamwork is transforming treatment options. Continue reading Spotlight on Cancer Research Month This May

- Tags Awareness Month , Cancer Research , Featured

The Role of Caregivers and 14 Amazing Resources to Help Them

Dive into our guide on the vital role of caregivers in the cancer journey. Explore the many resources available to help caregivers along the way. Continue reading The Role of Caregivers and 14 Amazing Resources to Help Them

- Post date February 29, 2024

Surviving Thyroid Cancer: Awesome Celebrity Stories of Hope

Get inspired by courageous stars like Missy Elliott, Sophia Vergara & Sia overcoming thyroid challenges. Their journeys could change your perspective. Continue reading Surviving Thyroid Cancer: Awesome Celebrity Stories of Hope

- Post date February 8, 2024

- Tags Cancer Survivors , Featured , Thyroid Cancer

Boost Your Cancer Fight: Quit Smoking and Alcohol Now!

Did you know you might double your chances of beating cancer by quitting smoking and alcohol today? Explore empowering strategies for a healthier life! Continue reading Boost Your Cancer Fight: Quit Smoking and Alcohol Now!

- Post date February 1, 2024

- Tags Advice for Patients , Resources , Treatment Options

5 Questions: How to Navigate Life After Thyroid Surgery

Navigate your journey through thyroid cancer surgery with confidence! Discover the top 5 questions to ask your doctor for a healthier recovery. Continue reading 5 Questions: How to Navigate Life After Thyroid Surgery

- Post date January 18, 2024

- Tags Advice for Patients , After Surgery , Featured , Post Treatment , Questions to Ask My Doctor , Thyroid Cancer

9 Useful Positive Coping Strategies After a Recent Diagnosis

Boost your quality of life with effective coping strategies for cancer! Discover positive techniques today to enhance recovery and well-being. Continue reading 9 Useful Positive Coping Strategies After a Recent Diagnosis

- Post date January 4, 2024

- Tags Advice for Patients , Communicating , Stress Management

Corporate Supporters

Help us keep this resource free.

Support the THANC Foundation, the creators of this resource.

Make a tax-deductible donation to support the THANC Foundation, the creators of the Thyroid, Head & Neck Cancer Guide.

Check out our blog: The Journey.

A little inspiration can go far.

A little inspiration can go far. Our blog addresses the unique hurdles each person faces.

Learn the Basics of Cancer

Find out things like what treatments are available and what happens if there's a recurrence.

The Cancer Basics section reveals things like how a diagnosis is reached, what treatments are available and what happens if there's a recurrence.

Read our Guide for Parents

Use the tools and advice inside and adapt them for your family.

Children and teenagers have unique interests and learn differently compared to adults. Parents can use the tools and advice inside and adapt them for their family.

Privacy Overview

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

The 5 Emotional Stages of People with Cancer

Common reactions, emotional stages, mental health side effects.

- Helping a Loved One

- When to Seek Care

Frequently Asked Questions

A cancer diagnosis can have a significant impact on the emotional health of you, your family, and your support system. You may experience fear, anxiety, sadness, anger and overwhelm. It’s completely normal to feel a wide range of emotions when facing a cancer diagnosis.

There are over 100 types of cancer, and an estimated 1.9 million people in the United States are diagnosed with cancer each year. Breast cancer, prostate cancer, and colorectal cancers account for nearly 50% of these cases.

FatCamera / Getty Images

When you are living with cancer, it's important to prioritize your emotional and physical health. Studies suggest that addressing the mental health concerns that people with cancer experience may lead to improved treatment outcomes and a better quality of life.

This article discusses the five emotional stages of cancer, how to cope, and how to help a loved one.

You may feel like you’re on an emotional rollercoaster after getting a cancer diagnosis. The range of emotions you feel can change daily, or even hourly.

Cancer Is an Emotional Experience

Though no two people will share the exact same emotions when facing cancer, common reactions to a cancer diagnosis include:

- Loneliness

Intense, varied emotions are common in people living with cancer—not just at the time of diagnosis, but at any point in your cancer treatment. You may grieve the loss of your good health, struggle with changes to your appearance, feel guilt over the impact your diagnosis has on your family, and worry about the future.

Developed by psychiatrist Elisabeth Kubler-Ross in 1969, the five stages of grief—commonly known as DABDA , which stands for "denial," "anger," "bargaining," "depression," and "acceptance"—may reflect the emotions you feel as you navigate your cancer journey. The DABDA model is a good tool to describe the emotional responses of people when they’re facing a life-changing illness or situation.

Although these stages are widely believed to happen in a linear fashion, these emotions can occur at any time, in any order, after a cancer diagnosis.

Getting a cancer diagnosis can be an overwhelming experience. The overwhelm may trigger feelings of disbelief, numbness, or shock. You may want to avoid thinking about it or pretend it isn’t happening. Denial is a common response to life-changing events and is a normal emotion for people with cancer. Denial will fade over time, and you will begin to experience other emotions concerning your diagnosis.

Anger is a natural emotional response to perceived threats. Though often not seen in a positive light, anger can be a good thing. When it comes to a cancer diagnosis, anger can be a vital part of the emotional process. It gives you a way to express your difficult emotions, like anxiety, fear, frustration, and helplessness.

It’s important to allow yourself to feel and express your anger in a healthy way rather than holding it all in. You may find it beneficial to talk about your anger with a trusted family member or friend (without taking it out on them), punch pillows, yell out loud in your car, write in a journal, or do a physical activity (e.g., dancing) to help you process your emotions.

Bargaining

In the bargaining stage, you may feel like your diagnosis is unfair and want to do anything to “fix” it and return to life pre-diagnosis. You may bargain with yourself or a higher power as a way of finding some control over the situation, and think things like, “If I get through this, I will never complain about anything again.” If your loved one has cancer, you may think, “If she survives this cancer, I will never again be angry at her.”

Bargaining and guilt often go hand in hand, and you may find yourself going through countless what-if scenarios, such as: What if I'd never smoked in my 20s? What if I'd never eaten junk food? What if I'd gone to the doctor six months earlier?

If you find yourself in an endless loop of bargaining, it may be helpful to talk through your emotions with a counselor or with peers in a cancer support group.

Depression is a common mental health condition that involves persistent feelings of sadness, loss of pleasure in previously enjoyed activities, and low energy. Depression can lead to changes in your sleeping and eating patterns, difficulty concentrating, and low self-worth.

Depression affects up to 1 in 4 people with cancer. Talk to your healthcare provider if these feelings persist for more than two weeks. They may recommend treatment to help manage your depression such as medication and/or counseling . Studies show that people with cancer who get treated for depression respond better to cancer treatments and have a higher quality of life.

Acceptance

Once you’ve given yourself the space to grieve and feel the emotions that come with a cancer diagnosis, it becomes easier to face your new reality head-on. This doesn’t mean you leave behind any difficult feelings or grief—rather, you learn to accept and find meaning in your current journey.

With acceptance comes hope. And there are plenty of reasons to feel hopeful—millions of people are cancer survivors . While there’s no evidence to suggest that a positive attitude can improve cancer treatment outcomes, there are still benefits to staying hopeful. A hopeful mindset is associated with stress reduction, lower blood pressure, and improved relationships.

Cancer Prognosis

A cancer prognosis is your healthcare provider’s best estimate of how your cancer will respond to treatment, how it will affect you, and what your chances of survival are. The type you have and the stage of cancer you're in, where the cancer is located in your body, your age, and how healthy you were before diagnosis all play a role in your prognosis.

It's important to remember that a prognosis is your cancer specialist's (oncologist) best guess and is not written in stone.

A cancer diagnosis can affect the mental health and well-being of people with cancer, their families, and caregivers.

Many people with cancer experience significant sadness and grieve the life they had before diagnosis. You may feel tired, have a reduced appetite, and find it difficult to get through your daily routine. This is normal, and it may take time for you to work through your feelings and accept your new way of life. Some cancer treatments may change your brain chemistry and increase the likelihood of depression.

Getting support from family members and friends or joining a cancer support group may help you process your emotions. If your feelings of depression persist, ask your healthcare provider about your options for treating depression. This may include medication and counseling.

Up to 45% of adults with cancer experience anxiety. Anxiety is feeling worried, afraid, tense, and/or unable to relax. Physical symptoms include a rapid heart rate, loss of appetite, nausea, dizziness, headaches, muscle pain, tightness in your chest, or changes in your sleep patterns.

It’s completely normal to feel anxious when you or your loved one is facing cancer. If you’re feeling anxious, it’s important to recognize this feeling and take the steps needed to manage how you feel.

Studies show that mindfulness-based activities (e.g., meditation, breathwork) are associated with a reduction of anxiety and depression in adults with cancer. Your doctor may suggest antianxiety medications and/or talk therapy to help manage anxiety.

How to Cope

Coping with cancer and the associated emotional toll is important. Though people cope with their emotions in different ways, you may find these strategies for coping helpful:

- Recognize and be honest about what you’re feeling.

- Talk about your feelings with a trusted loved one.

- Seek out community, such as a cancer support group.

- Eat a balanced, nutritious diet .

- Get plenty of sleep.

- Engage in physical activity (e.g., walking, swimming).

- Try relaxation techniques, such as meditation, mindfulness, breathwork, or yoga

- Write your feelings down in a journal.

- Look for positive experiences—whether that’s with a beloved pet, friends, or a solo activity that brings joy.

- Talk to your healthcare providers if your feelings of depression and/or anxiety persist.

How to Help

If your family member or friend has been diagnosed with cancer, you may be wondering what you can do to help. Here are some ideas on how to support a loved one with cancer :

- Listen : Ask how they’re feeling and provide a listening ear.

- Offer to help : Whether you cook meals, do their laundry, or provide transportation to their appointments, helping with day-to-day tasks is often appreciated.

- Treat them the same : Your loved one is the same person they were before the diagnosis, and treating them as you have in the past is a way to provide normalcy.

- Give them a cancer break : People with cancer often need a break from talking about all things cancer-related. Share interesting stories, some laughs, or sit down for a cozy movie night together.

- Learn about cancer : Taking the initiative to learn about your loved one’s cancer type and treatments is a way to show you care.

- Show up : Stay consistent with your relationship—call, text, or take time for visits to let them know you’re a reliable friend.

Remember that you can’t pour from an empty cup. If you are a caregiver, be sure to carve out time for self-care—being there for a loved one with cancer can take an emotional and physical toll on caregivers, too. Taking care of your own needs can give you the strength you need to continue providing support.

When to See a Healthcare Provider

If your emotions are affecting your day-to-day life or lasting a long time, your cancer care team can help. Ask your healthcare team for mental health support. Your oncologist may refer you to a counselor who can help you learn how to cope with your diagnosis. They may also prescribe medication, such as an antidepressant or antianxiety medications.

Receiving a cancer diagnosis is an emotionally overwhelming experience that can lead you to experience feelings of denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and eventually acceptance. However, the journey is not linear, and not everyone experiences each of these emotions.

That said, receiving a cancer diagnosis or learning your loved one has cancer can contribute to feelings of sadness, anxiety, and hopelessness. It's normal and okay to feel sad, but if you or a loved one is experiencing these emotions for an extended period of time and/or are having trouble coping, it doesn't hurt to ask for help.

A Word From Verywell

Coping with a cancer diagnosis—whether it is your own or a loved one’s—can take a psychological toll. Give yourself the space to acknowledge and express all of your feelings openly and honestly.

If you feel your emotional health is negatively affecting your daily life, talk to your healthcare provider. There is no shame in asking for help—even the strongest, most resilient people need support. Asking for mental health support is one of the best things you can do for yourself as you navigate your cancer journey.

Whether cancer can be cured depends on the type and stage of cancer, how a person responds to treatment, and other factors. A cure means that cancer has gone away with treatment and will never come back. Remission is when cancer has responded to treatment and all signs and symptoms have gone away. If a person remains in remission for five or more years, they may say they are cured.

Most types of cancer have four stages: stage 1, stage 2, stage 3, and stage 4 (sometimes written in Roman numerals as I, II, III, and IV). Some cancers have stage 0. Staging is a way to indicate cancer’s location, size, and whether or not it has spread (metastasized) either locally or farther from the original site. Staging helps doctors determine the best treatment plan (e.g., chemotherapy, surgery).

National Cancer Institute. What is cancer?

National Cancer Institute. Cancer stat facts: common cancer sites.

Mental Health America. Cancer and mental health.

National Cancer Institute. Cancer and feelings.

Stroebe M, Schut H, Boerner K. Cautioning healthcare professionals . Omega (Westport) . 2017;74(4):455-473. doi:10.1177/0030222817691870

Conley CC, Bishop BT, Andersen BL. Emotions and emotion regulation in breast cancer survivorship . Healthcare (Basel) . 2016;4(3):56. doi:10.3390/healthcare4030056

American Society for Clinical Oncology. Coping with anger.

Living Beyond Breast Cancer. Emotional stages of a breast cancer diagnosis.

National Institute of Mental Health. Major depression.

American Cancer Society. Depression.

Smith HR. Depression in cancer patients: Pathogenesis, implications and treatment (review) . Oncol Lett . 2015;9(4):1509-1514. doi:10.3892/ol.2015.2944

National Cancer Institute. Cancer and feelings.

National Cancer Institute. Understanding cancer prognosis .

National Behavioral Health Network. Mental health impacts of a cancer diagnosis.

Zhang MF, Wen YS, Liu WY, Peng LF, Wu XD, Liu QW. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based therapy for reducing anxiety and depression in patients with cancer: a meta-analysis . Medicine (Baltimore) . 2015;94(45):e0897. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000000897

Canadian Cancer Society. Coping with emotions.

CancerCare. What can I say to a newly diagnosed loved one?

American Society of Clinical Oncology. Counseling .

American Cancer Society. Can cancer be cured?

American Society of Clinical Oncology. Stages of cancer.

By Lindsay Curtis Curtis is a writer with over 20 years of experience focused on mental health, sexual health, cancer care, and spinal health.

Lessons From My Cancer Journey

A personal perspective: hard lessons for a reluctant learner..

Posted August 18, 2022 | Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

After being diagnosed with head and neck cancer in February 2021 and overcoming the shock of what was in store for me, I realized that I had embarked on a journey that I hadn’t planned on taking. The journey would be arduous, comprised of hazardous twists and turns and lessons I hadn’t expected or thought I needed to learn.

I also learned that my cancer was going to be my teacher, and it had no regard for students who displayed a reluctance to learn or whether or not I grew tired from the difficult journey as it would unfold.

My cancer was a harsh and severe teacher; unmerciful, unkind, and unrelenting. Early on, I realized that the metaphor of a war or battle didn’t capture what I was experiencing.

I am writing this about my experience because others can benefit from the lessons I’ve learned. These lessons are especially important for men. Like me, most men are socialized to be stoics: to tough it out when things are hard, to not ask for help even when we desperately need it, and to not seek medical help even when the signs of trouble are clear. As you will see, I learned to reject stoicism and embrace my vulnerability.

I came to think of my cancer as a teacher, one who was a lot like my freshman philosophy professor. He was the quintessential New England Ivy League professor: tweed jacket, wire-rimmed glasses, and a dour expression of judgment permanently on his unfriendly face. Never warm or friendly, he was consistently stern and serious. He approached teaching and his students as if administering a form of punishment in each lecture, and he did so without a hint of compassion.

This professor enjoyed utilizing the Socratic method when teaching. He took special delight in cold-calling on students, especially those who appeared distracted or unprepared. He did not care if his pointed yet thoughtful questions left an uncertain or unprepared student embarrassed or ashamed; that was the point of the questioning. Whether you were prepared, sleepy , distracted, or not, he was there to deliver a set of lessons through a series of probing questions that pushed us to think in ways our young minds were often not ready for.

I found that my cancer lessons were a lot like my experience in freshman philosophy, except I hadn’t chosen to take the course. For some reason, I was required to take this journey and compelled to learn the lessons along the way. Like my professor, my cancer teacher had no patience for unprepared students.

“Why me?” I thought as my cancer journey commenced. I soon came to realize how stupid the question was. My cancer teacher could care less if I felt sorry for myself or if I thought having this disease was unfair. There would be no time for wallowing in self-pity on my cancer journey, and the lessons I would be forced to learn along the way would be taught without patience or compassion. My first lesson was that “why me” was the wrong question.

In her book, Illness as Metaphor (1978), Susan Sontag wrote:

Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick. Although we all prefer to use the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.

When I was diagnosed with cancer in February 2021, I began my journey to the kingdom of the sick. I hoped I would merely be a tourist passing through, unlike others I had known who became permanent residents in that horrid and unforgiving land.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, six in every 10 adults in the United States have a chronic disease. Four in 10 have two illnesses or more. I had no desire to become a member of this sickly tribe, but here I was.

Pedro Antonio Noguera, Ph.D., is the Emery Stoops and Joyce King Stoops Dean of the Rossier School of Education and a Distinguished Professor of Education at the University of Southern California.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer

- Bile Duct Cancer

- Bladder Cancer

- Brain Cancer

- Breast Cancer

- Cervical Cancer

- Childhood Cancer

- Colorectal Cancer

- Endometrial Cancer

- Esophageal Cancer

- Head and Neck Cancer

- Kidney Cancer

- Liver Cancer

- Lung Cancer

- Mouth Cancer

- Mesothelioma

- Multiple Myeloma

- Neuroendocrine Tumors

- Ovarian Cancer

- Pancreatic Cancer

- Prostate Cancer

- Skin Cancer/Melanoma

- Stomach Cancer

- Testicular Cancer

- Throat Cancer

- Thyroid Cancer

- Prevention and Screening

- Diagnosis and Treatment

- Research and Clinical Trials

- Survivorship

Request an appointment at Mayo Clinic

Integrative oncology: Lifestyle medicine for people with cancer

Share this:.

By Nicole Brudos Ferrara

Integrative medicine combines conventional Western medicine with complementary and alternative treatments that have been researched and proven to be safe and effective in healing. Integrative oncology uses integrative medicine as part of standard cancer care.

"Integrative oncology is a practice where we use lifestyle medicine like dietary modifications, stress reduction, exercise, supplements and mind-body practices," says Stacy D'Andre, M.D., a Mayo Clinic medical and integrative oncologist. "We combine all of these practices to help our cancer patients improve quality of life and hopefully improve treatment outcomes, as well."

Integrative oncology can help people with cancer feel better by reducing the fatigue, nausea, pain, anxiety and other symptoms that can come with cancer and cancer treatment.

If you are living with cancer or caring for someone who is, here's an overview of how integrative oncology can ease the burden of cancer:

Integrative oncology starts with healthy habits.

Integrative oncologists help people develop healthy habits to better cope with the stress of living with cancer. "Lifestyle issues are really the foundation of what we work on. Diet, exercise, stress and sleep — all of these things are the foundation to improving health in general,” says Dr. D'Andre.

Dr. D'Andre says healthy habits during cancer treatment are the same habits everyone should adopt for optimal health:

- Eat a diet rich in fruits and vegetables, and choose whole grains and lean proteins.

- Limit your intake of processed and red meats.

- Exercise regularly. Aim for at least 30 minutes of exercise most days of the week.

- Practice good sleep hygiene to achieve at least seven hours of sleep per night.

- Work to achieve and maintain a healthy weight.

- If you choose to drink alcohol, do so in moderation.

- If you smoke, quit . If you don't smoke, don't start.

- Limit your sun exposure, wear protective clothing and apply sunscreen.

Integrative oncology can help people at each stage of the cancer journey.

Receiving a cancer diagnosis and making decisions about treatment can cause stress. Cancer can cause a long list of signs and symptoms, including fatigue and pain. Conventional treatments for cancer, including surgery, chemotherapy and radiation, also can cause fatigue, pain and stress, as well as nausea, diarrhea or constipation, weight loss and other complications. And some of these complications linger after treatment has ended.

Integrative oncologists counsel people receiving cancer treatment on practices that can help relieve these side effects and improve treatment outcomes. They help cancer patients adopt a healthy lifestyle and lose weight, understand which herbal and dietary supplements are safe to take, and recommend integrative medicine practices that might help manage a person's symptoms.

"We also see people after they've completed cancer treatment to help them cope with lingering symptoms and lifestyle modification," says Dr. D'Andre.

When treatment is not an option as part of palliative care , integrative oncologists also can help people manage their symptoms and quality of life.

Integrative oncology is individualized for each patient.

Integrative oncologists work with patients to determine which integrative medicine practices might work well based on individual needs. Health care professionals can now choose from a range of evidence-based approaches that may help, including:

- Acupuncture and acupressure During acupuncture treatment, a practitioner inserts tiny needles into your skin at precise points. Studies show acupuncture may help relieve nausea caused by chemotherapy. Acupuncture also may help relieve certain types of pain in people with cancer. Acupressure is a technique related to acupuncture where mild pressure is applied to certain areas, such as the wrist, to help relieve nausea.

- Aromatherapy In aromatherapy , fragrant oils are used to provide a calming sensation. Oils, infused with scents such as lavender, can be applied to your skin during a massage, or the oils can be added to bath water. Fragrant oils also can be heated to release their scents into the air. Aromatherapy may help relieve nausea, pain and stress.

- Exercise Adding more movement to your day may help you manage signs and symptoms during and after cancer treatment. Gentle exercise may help relieve fatigue and stress and help you sleep better. Many studies show that an exercise program may help people with cancer live longer and improve their overall quality of life.

- Massage During a massage , your practitioner kneads your skin, muscles and tendons in an effort to relieve muscle tension and stress, and promote relaxation. Studies have found that massage can help relieve pain in people with cancer. It also can help relieve anxiety, fatigue and stress.

- Meditation The practice of meditation involves focusing your mind on one image, sound or idea, such as a positive thought, to reach a state of deep concentration. When meditating, you also might perform deep-breathing or relaxation exercises. Meditation may help people with cancer by relieving anxiety and stress, and improving mood.

- Music therapy During music therapy sessions, you might listen to music, play instruments, sing songs or write lyrics. A trained music therapist may lead you through activities designed to meet your specific needs, or you may participate in music therapy in a group setting. Music therapy may help relieve pain, control nausea and vomiting, and deal with anxiety and stress.

- Relaxation techniques Relaxation techniques focus your attention on calming your mind and relaxing your muscles. They might include visualization exercises or progressive muscle relaxation. Relaxation techniques may help relieve anxiety and fatigue. They also may help people with cancer sleep better.

- Tai chi This form of exercise incorporates gentle movements and deep breathing. Tai chi can be led by an instructor, or you can learn tai chi on your own following books or videos. Practicing tai chi may help relieve stress.

- Yoga This activity combines stretching exercises with deep breathing. During a yoga session, you position your body in various poses that require bending, twisting and stretching. Yoga may provide some stress relief for people with cancer, and it has been shown to improve sleep and reduce fatigue.

Integrative oncology is growing in acceptance and popularity.

Integrative oncology is a new field, and trained integrative oncologists are not yet easy to find, according to Dr. D'Andre. But integrative medicine is now being used at many cancer centers.

"There's a huge patient demand for this. There are integrative medicine practices now at most major academic centers and even in the community, which is different than it has been in the past," says Dr. D'Andre.

If your health care team doesn't have an integrative oncologist on staff, ask if an integrative medicine program in the area can help.

"The great thing about this type of practice is that it really empowers the patient," says Dr. D'Andre. "They're the ones doing the work — working on their diet, doing the exercise — we're just guiding them. These are things they can do and control to improve their health and outcomes."

Watch this "Mayo Clinic Q&A" podcast video to hear Dr. D'Andre explain how integrative oncology helps people with cancer and discuss integrative medicine research underway at Mayo Clinic:

Mayo Clinic's Cancer Education Center offers free virtual classes that explore integrative medicine practices. Learn more .

Also read these articles:

- "7 steps to better nutrition habits for cancer survivors ."

- "Alternative cancer treatments: 11 options to consider ."

- "Integrative health paves road to recovery for young breast cancer patient ."

Online Help

Our 24/7 cancer helpline provides information and answers for people dealing with cancer. We can connect you with trained cancer information specialists who will answer questions about a cancer diagnosis and provide guidance and a compassionate ear.

Chat live online

Select the Live Chat button at the bottom of the page

Call us at 1-800-227-2345

Available any time of day or night

Our highly trained specialists are available 24/7 via phone and on weekdays can assist through online chat. We connect patients, caregivers, and family members with essential services and resources at every step of their cancer journey. Ask us how you can get involved and support the fight against cancer. Some of the topics we can assist with include:

- Referrals to patient-related programs or resources

- Donations, website, or event-related assistance

- Tobacco-related topics

- Volunteer opportunities

- Cancer Information

For medical questions, we encourage you to review our information with your doctor.

Road To Recovery®

Get a free ride to cancer treatment .

The American Cancer Society Road To Recovery® program eases your burden by giving free rides to cancer-related medical appointments. Our trained volunteer drivers are happy to pick you up, take you to your appointment, and drop you off at home. All for free and all to make your days a little easier. Not having a ride shouldn’t stand between you and lifesaving treatment.

Schedule a ride with Road To Recovery®

Connect with us by calling 1-800-227-234 5 . to learn more about Road To Recovery® availability near you and other resources to help you on your cancer journey.

Am I eligible?

Patients must be traveling to a cancer-related medical appointment.

Other eligibility requirements may apply. For example, a caregiver may need to accompany a patient who cannot walk without help, or is under age 18. Contact us to find out what is available in your area, and what the specific requirements are.

It can take several business days to coordinate your ride, so please call us at 1-800-227-2345 well in advance of your appointment date.

How do I become a Road To Recovery® Volunteer?

Volunteering as a Road To Recovery® driver will put you at the heart of the American Cancer Society’s mission and fulfill a critical need for cancer patients. If you own or have regular access to a safe, reliable vehicle, then you’re already on the road to volunteering.

Volunteer drivers must be between the ages of 18 and 84, have a valid driver’s license, pass a background check, and have access to a safe, reliable car.

To learn more about becoming a Road To Recovery® volunteer, please visit our Road To Recovery® volunteer page, linked below.

Our Road To Recovery® program is made possible thanks to generous supporters like you.

Donate today or sign up to volunteer so we can continue our life-changing work.

Help us end cancer as we know it, for everyone.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Breast cancer patient experiences through a journey map: A qualitative study

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Clinical Psychology and Psychobiology Department, Faculty of Psychology, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Medical Oncology Department Hospital Universitario Central of Asturias, Oviedo, Spain

Roles Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Social Psychology and Quantitative Psychology Department, Faculty of Psychology, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Affiliation Medical Oncology Department, Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos, Madrid, Spain

Affiliation Medical Oncology Department, Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense, Ourense, Spain

Affiliation Medical Oncology Department, Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid, Spain

Affiliation Medical Oncology Department, Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Elche, Spain

Affiliation Medical Oncology Department, Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón, Madrid, Spain

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

- Laura Ciria-Suarez,

- Paula Jiménez-Fonseca,

- María Palacín-Lois,

- Mónica Antoñanzas-Basa,

- Ana Fernández-Montes,

- Aranzazu Manzano-Fernández,

- Beatriz Castelo,

- Elena Asensio-Martínez,

- Susana Hernando-Polo,

- Caterina Calderon

- Published: September 22, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257680

- Reader Comments

Registered Report Protocol

21 Dec 2020: Ciria-Suarez L, Jiménez-Fonseca P, Palacín-Lois M, Antoñanzas-Basa M, Férnández-Montes A, et al. (2020) Ascertaining breast cancer patient experiences through a journey map: A qualitative study protocol. PLOS ONE 15(12): e0244355. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244355 View registered report protocol

Breast cancer is one of the most prevalent diseases in women. Prevention and treatments have lowered mortality; nevertheless, the impact of the diagnosis and treatment continue to impact all aspects of patients’ lives (physical, emotional, cognitive, social, and spiritual).

This study seeks to explore the experiences of the different stages women with breast cancer go through by means of a patient journey.

This is a qualitative study in which 21 women with breast cancer or survivors were interviewed. Participants were recruited at 9 large hospitals in Spain and intentional sampling methods were applied. Data were collected using a semi-structured interview that was elaborated with the help of medical oncologists, nurses, and psycho-oncologists. Data were processed by adopting a thematic analysis approach.

The diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer entails a radical change in patients’ day-to-day that linger in the mid-term. Seven stages have been defined that correspond to the different medical processes: diagnosis/unmasking stage, surgery/cleaning out, chemotherapy/loss of identity, radiotherapy/transition to normality, follow-up care/the “new” day-to-day, relapse/starting over, and metastatic/time-limited chronic breast cancer. The most relevant aspects of each are highlighted, as are the various cross-sectional aspects that manifest throughout the entire patient journey.

Conclusions

Comprehending patients’ experiences in depth facilitates the detection of situations of risk and helps to identify key moments when more precise information should be offered. Similarly, preparing the women for the process they must confront and for the sequelae of medical treatments would contribute to decreasing their uncertainty and concern, and to improving their quality-of-life.

Citation: Ciria-Suarez L, Jiménez-Fonseca P, Palacín-Lois M, Antoñanzas-Basa M, Fernández-Montes A, Manzano-Fernández A, et al. (2021) Breast cancer patient experiences through a journey map: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 16(9): e0257680. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257680

Editor: Erin J. A. Bowles, Kaiser Permanente Washington, UNITED STATES

Received: February 17, 2021; Accepted: September 3, 2021; Published: September 22, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Ciria-Suarez et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Relevant anonymized data excerpts from the transcripts are in the main body of the manuscript. They are supported by the supplementary documentation at 10.1371/journal.pone.0244355 .

Funding: This work was funded by the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology (SEOM) in 2018. The sponsor of this research has not participated in the design of research, in writing the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer and the one that associates the highest mortality rates among Spanish women, with 32,953 new cases estimated to be diagnosed in Spain in 2020 [ 1 ]. Thanks to early diagnosis and therapeutic advances, survival has increased in recent years [ 2 ]. The 5-year survival rate is currently around 85% [ 3 , 4 ].

Though high, this survival rate is achieved at the expense of multiple treatment modalities, such as surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and hormone therapy, the side effects and sequelae of which can interfere with quality-of-life [ 5 ]. Added to this is the uncertainty surrounding prognosis; likewise, life or existential crises are not uncommon, requiring great effort to adjust and adapt [ 6 ]. This will not only affect the patient psychologically, but will also impact their ability to tolerate treatment and their socio-affective relations [ 7 ].

Several medical tests are performed (ultrasound, mammography, biopsy, CT, etc.) to determine tumor characteristics and extension, and establish prognosis [ 8 ]. Once diagnosed, numerous treatment options exist. Surgery is the treatment of choice for non-advanced breast cancer; chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and hormone therapy are adjuvant treatments with consolidated benefit in diminishing the risk of relapse and improving long-term survival [ 9 ]. Breast cancer treatments prompt changes in a person’s physical appearance, sexuality, and fertility that interfere with their identity, attractiveness, self-esteem, social relationships, and sexual functioning [ 10 ]. Patients also report more fatigue and sleep disturbances [ 11 ]. Treatment side effects, together with prognostic uncertainty cause the woman to suffer negative experiences, such as stress in significant relationships, and emotions, like anxiety, sadness, guilt, and/or fear of death with negative consequences on breast cancer patients’ quality-of-life [ 10 , 12 ]. Once treatment is completed, patients need time to recover their activity, as they report decreased bodily and mental function [ 13 ], fear of relapse [ 14 ], and changes in employment status [ 15 ]. After a time, there is a risk of recurrence influenced by prognostic factors, such as nodal involvement, size, histological grade, hormone receptor status, and treatment of the primary tumor [ 16 ]. Thirty percent (30%) of patients with early breast cancer eventually go on to develop metastases [ 17 ]. There is currently no curative treatment for patients with metastatic breast cancer; consequently, the main objectives are to prolong survival, enhance or maintain quality-of-life, and control symptoms [ 17 , 18 ]. In metastatic stages, women and their families are not only living with uncertainty about the future, the threat of death, and burden of treatment, but also dealing with the existential, social, emotional, and psychological difficulties their situation entails [ 18 , 19 ].

Supporting and accompanying breast cancer patients throughout this process requires a deep understanding of their experiences. To describe the patient’s experiences, including thoughts, emotions, feelings, worries, and concerns, the phrase “patient voice” has been used, which is becoming increasingly common in healthcare [ 20 ]. Insight into this “voice” allows us to delve deeper into the physical, emotional, cognitive, social, and spiritual effects of the patient’s life. This narrative can be portrayed as a “cancer journey", an experiential map of patients’ passage through the different stages of the disease [ 21 ] that captures the path from prevention to early diagnosis, acute care, remission, rehabilitation, possible recurrence, and terminal stages when the disease is incurable and progresses [ 22 ]. The term ‘patient journey’ has been used extensively in the literature [ 23 – 25 ] and is often synonymous with ‘patient pathway’ [ 26 ]. Richter et al. [ 26 ] state that there is no common definition, albeit in some instances the ‘patient journey’ comprises the core concept of the care pathway with greater focus on the individual and their perspective (needs and preferences) and including mechanisms of engagement and empowerment.

While the patient’s role in the course of the disease and in medical decision making is gaining interest, little research has focused on patient experiences [ 27 , 28 ]. Patient-centered care is an essential component of quality care that seeks to improve responsiveness to patients’ needs, values, and predilections and to enhance psychosocial outcomes, such as anxiety, depression, unmet support needs, and quality of life [ 29 ]. Qualitative studies are becoming more and more germane to grasp specific aspects of breast cancer, such as communication [ 27 , 30 ], body image and sexuality [ 31 , 32 ], motherhood [ 33 ], social support [ 34 ], survivors’ reintegration into daily life [ 13 , 15 ], or care for women with incurable, progressive cancer [ 17 ]. Nevertheless, few published studies address the experience of women with breast cancer from diagnosis to follow-up. These include a clinical pathway approach in the United Kingdom in the early 21st century [ 35 ], a breast cancer patient journey in Singapore [ 25 ], a netnography of breast cancer patients in a French specialized forum [ 28 ], a meta-synthesis of Australian women living with breast cancer [ 36 ], and a systematic review blending qualitative studies of the narratives of breast cancer patients from 30 countries [ 37 ]. Sanson-Fisher et al. [ 29 ] concluded that previously published studies had examined limited segments of patients’ experiences of cancer care and emphasized the importance of focusing more on their experiences across multiple components and throughout the continuum of care. Therefore, the aim of this study is to depict the experiences of Spanish breast cancer patients in their journey through all stages of the disease. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies that examine the experience of women with breast cancer in Spain from diagnosis through treatment to follow-up of survivors and those who suffer a relapse or incurable disease presented as a journey map.

A map of the breast cancer patient’s journey will enable healthcare professionals to learn first-hand about their patients’ personal experiences and needs at each stage of the disease, improve communication and doctor-patient rapport, thereby creating a better, more person-centered environment. Importantly, understanding the transitional phases and having a holistic perspective will allow for a more holistic view of the person. Furthermore, information about the journey can aid in shifting the focus of health care toward those activities most valued by the patient [ 38 ]. This is a valuable and efficient contribution to the relationship between the system, medical team, and patients, as well as to providing resources dedicated to the patient’s needs at any given time, thus improving their quality of life and involving them in all decisions.

Study design and data collection

We conducted a qualitative study to explore the pathway of standard care for women with breast cancer and to develop a schematic map of their journey based on their experiences. A detailed description of the methodology is reported in the published protocol “Ascertaining breast cancer patient experiences through a journey map: A qualitative study protocol” [ 39 ].

An interview guide was created based on breast cancer literature and adapted with the collaboration of two medical oncologists, three nurses (an oncology nurse from the day hospital, a case manager nurse who liaises with the different services and is the ‘named’ point of contact for breast cancer patients for their journey throughout their treatment, and a nurse in charge of explaining postoperative care and treatment), and two psycho-oncologists. The interview covered four main areas. First, sociodemographic and medical information. Second, daily activities, family, and support network. Third, participants were asked about their overall perception of breast cancer and their coping mechanisms. Finally, physical, emotional, cognitive, spiritual, and medical aspects related to diagnosis, treatment, and side effects were probed. Additionally, patients were encouraged to express their thoughts should they want to expand on the subject.

The study was carried out at nine large hospitals located in six geographical areas of Spain. To evaluate the interview process, a pilot test was performed. Interviews were conducted using the interview guide by the principal investigator who had previous experience in qualitative research. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, all interviews were completed online and video recorded with the consent of the study participants for subsequent transcription. Relevant notes were taken during the interview to document key issues and observations.

Participant selection and recruitment