The Enlightened Mindset

Exploring the World of Knowledge and Understanding

Welcome to the world's first fully AI generated website!

Is Time Travel Illegal? An In-depth Look at the Legal Implications of Time Travel

By Happy Sharer

Introduction

Time travel is a concept that has been present in science fiction for decades. From Doctor Who to Back To The Future, these stories often explore the idea of travelling through time, either for entertainment or for more serious purposes. But is time travel actually illegal? This article will explore the legal implications of time travel, examining the laws that govern it and looking at the potential consequences of breaking those laws.

Examining Laws Across Time & Space: Is Time Travel Illegal?

When it comes to time travel, there are few laws that explicitly state whether it is allowed or not. Instead, the legality of time travel is determined by the laws that govern space and time. These laws vary from country to country, but they all have one thing in common: they prohibit any activity that may interfere with the normal flow of time.

For example, in the United States, federal laws prohibit the use of time travel devices without a license. In the UK, the Offences Against the Person Act 1861 makes it illegal to use time travel technology. This means that, even if you have the right equipment, you could still be breaking the law if you attempt to travel through time.

However, the legality of time travel is not always clear cut. Some countries have laws that specifically address the issue, while others simply refer to laws that cover other areas such as space exploration or physics. This means that the legality of time travel can vary depending on where you are located.

Exploring the Legal Implications of Time Travel: Is It Allowed?

The legal implications of time travel depend largely on the laws of the country in which you are travelling. For example, in some countries, the laws governing time travel are stricter than those governing space exploration. This means that, even if you have the right equipment, you could still be breaking the law if you attempt to travel through time.

In addition to the laws that govern time travel, there are also ethical considerations to take into account. For instance, if you were to travel back in time, you could potentially disrupt the timeline and cause irreparable damage to the future. This could mean that, even if you were able to travel through time legally, the consequences could be far-reaching and devastating.

Can You Break the Law by Travelling Through Time?

The answer to this question depends largely on the laws of the country in which you are travelling. In some countries, time travel is strictly prohibited, while in others it is only illegal when used for malicious purposes. In either case, it is important to understand the laws governing time travel in your area before attempting to travel through time.

In addition to understanding the local laws, it is also important to consider the ethical implications of time travel. As mentioned above, travelling through time could have far-reaching consequences, and it is important to consider these carefully before deciding whether or not to attempt time travel.

Is Time Travel a Crime? An Analysis of Current Laws

In most countries, time travel is not considered a crime. However, there are some exceptions. For instance, in the United States, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) considers time travel to be a form of tampering with evidence, and thus it is illegal. In the UK, the Offences Against the Person Act 1861 makes it illegal to use time travel technology for malicious purposes.

In addition to the laws governing time travel, there are also potential repercussions for those who attempt to travel through time. These can include fines, imprisonment, and even death. It is therefore important to consider the potential consequences of time travel before attempting it.

Time travel is a fascinating concept, but it is important to understand the legal and ethical implications before attempting it. Laws governing time travel vary from country to country, but they generally prohibit any activity that interferes with the normal flow of time. In addition, there are potential repercussions for those who attempt to travel through time, including fines, imprisonment, and even death.

If you are considering travelling through time, it is important to research the laws in your area and to consider the potential consequences before making a decision. By understanding the legal and ethical implications of time travel, you can make an informed decision about whether or not to attempt it.

(Note: Is this article not meeting your expectations? Do you have knowledge or insights to share? Unlock new opportunities and expand your reach by joining our authors team. Click Registration to join us and share your expertise with our readers.)

Hi, I'm Happy Sharer and I love sharing interesting and useful knowledge with others. I have a passion for learning and enjoy explaining complex concepts in a simple way.

Related Post

Exploring japan: a comprehensive guide for your memorable journey, your ultimate guide to packing for a perfect trip to hawaii, the ultimate packing checklist: essentials for a week-long work trip, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Expert Guide: Removing Gel Nail Polish at Home Safely

Trading crypto in bull and bear markets: a comprehensive examination of the differences, making croatia travel arrangements, make their day extra special: celebrate with a customized cake.

An official website of the United States government.

Here’s how you know

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- American Rescue Plan

- Coronavirus Resources

- Disability Resources

- Disaster Recovery Assistance

- Equal Employment Opportunity

- Guidance Search

- Health Plans and Benefits

- Registered Apprenticeship

- International Labor Issues

- Labor Relations

- Leave Benefits

- Major Laws of DOL

- Other Benefits

- Retirement Plans, Benefits and Savings

- Spanish-Language Resources

- Termination

- Unemployment Insurance

- Veterans Employment

- Whistleblower Protection

- Workers' Compensation

- Workplace Safety and Health

- Youth & Young Worker Employment

- Breaks and Meal Periods

- Continuation of Health Coverage - COBRA

- FMLA (Family and Medical Leave)

- Full-Time Employment

- Mental Health

- Office of the Secretary (OSEC)

- Administrative Review Board (ARB)

- Benefits Review Board (BRB)

- Bureau of International Labor Affairs (ILAB)

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)

- Employee Benefits Security Administration (EBSA)

- Employees' Compensation Appeals Board (ECAB)

- Employment and Training Administration (ETA)

- Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA)

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA)

- Office of Administrative Law Judges (OALJ)

- Office of Congressional & Intergovernmental Affairs (OCIA)

- Office of Disability Employment Policy (ODEP)

- Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP)

- Office of Inspector General (OIG)

- Office of Labor-Management Standards (OLMS)

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Administration and Management (OASAM)

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Policy (OASP)

- Office of the Chief Financial Officer (OCFO)

- Office of the Solicitor (SOL)

- Office of Workers' Compensation Programs (OWCP)

- Ombudsman for the Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program (EEOMBD)

- Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC)

- Veterans' Employment and Training Service (VETS)

- Wage and Hour Division (WHD)

- Women's Bureau (WB)

- Agencies and Programs

- Meet the Secretary of Labor

- Leadership Team

- Budget, Performance and Planning

- Careers at DOL

- Privacy Program

- Recursos en Español

- News Releases

- Economic Data from the Department of Labor

- Email Newsletter

Travel Time

Time spent traveling during normal work hours is considered compensable work time. Time spent in home-to-work travel by an employee in an employer-provided vehicle, or in activities performed by an employee that are incidental to the use of the vehicle for commuting, generally is not "hours worked" and, therefore, does not have to be paid. This provision applies only if the travel is within the normal commuting area for the employer's business and the use of the vehicle is subject to an agreement between the employer and the employee or the employee's representative.

Webpages on this Topic

Handy Reference Guide to the Fair Labor Standards Act - Answers many questions about the FLSA and gives information about certain occupations that are exempt from the Act.

Coverage Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) Fact Sheet - General information about who is covered by the FLSA.

Wage and Hour Division: District Office Locations - Addresses and phone numbers for Department of Labor district Wage and Hour Division offices.

State Labor Offices/State Laws - Links to state departments of labor contacts. Individual states' laws and regulations may vary greatly. Please consult your state department of labor for this information.

April 26, 2023

Is Time Travel Possible?

The laws of physics allow time travel. So why haven’t people become chronological hoppers?

By Sarah Scoles

yuanyuan yan/Getty Images

In the movies, time travelers typically step inside a machine and—poof—disappear. They then reappear instantaneously among cowboys, knights or dinosaurs. What these films show is basically time teleportation .

Scientists don’t think this conception is likely in the real world, but they also don’t relegate time travel to the crackpot realm. In fact, the laws of physics might allow chronological hopping, but the devil is in the details.

Time traveling to the near future is easy: you’re doing it right now at a rate of one second per second, and physicists say that rate can change. According to Einstein’s special theory of relativity, time’s flow depends on how fast you’re moving. The quicker you travel, the slower seconds pass. And according to Einstein’s general theory of relativity , gravity also affects clocks: the more forceful the gravity nearby, the slower time goes.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“Near massive bodies—near the surface of neutron stars or even at the surface of the Earth, although it’s a tiny effect—time runs slower than it does far away,” says Dave Goldberg, a cosmologist at Drexel University.

If a person were to hang out near the edge of a black hole , where gravity is prodigious, Goldberg says, only a few hours might pass for them while 1,000 years went by for someone on Earth. If the person who was near the black hole returned to this planet, they would have effectively traveled to the future. “That is a real effect,” he says. “That is completely uncontroversial.”

Going backward in time gets thorny, though (thornier than getting ripped to shreds inside a black hole). Scientists have come up with a few ways it might be possible, and they have been aware of time travel paradoxes in general relativity for decades. Fabio Costa, a physicist at the Nordic Institute for Theoretical Physics, notes that an early solution with time travel began with a scenario written in the 1920s. That idea involved massive long cylinder that spun fast in the manner of straw rolled between your palms and that twisted spacetime along with it. The understanding that this object could act as a time machine allowing one to travel to the past only happened in the 1970s, a few decades after scientists had discovered a phenomenon called “closed timelike curves.”

“A closed timelike curve describes the trajectory of a hypothetical observer that, while always traveling forward in time from their own perspective, at some point finds themselves at the same place and time where they started, creating a loop,” Costa says. “This is possible in a region of spacetime that, warped by gravity, loops into itself.”

“Einstein read [about closed timelike curves] and was very disturbed by this idea,” he adds. The phenomenon nevertheless spurred later research.

Science began to take time travel seriously in the 1980s. In 1990, for instance, Russian physicist Igor Novikov and American physicist Kip Thorne collaborated on a research paper about closed time-like curves. “They started to study not only how one could try to build a time machine but also how it would work,” Costa says.

Just as importantly, though, they investigated the problems with time travel. What if, for instance, you tossed a billiard ball into a time machine, and it traveled to the past and then collided with its past self in a way that meant its present self could never enter the time machine? “That looks like a paradox,” Costa says.

Since the 1990s, he says, there’s been on-and-off interest in the topic yet no big breakthrough. The field isn’t very active today, in part because every proposed model of a time machine has problems. “It has some attractive features, possibly some potential, but then when one starts to sort of unravel the details, there ends up being some kind of a roadblock,” says Gaurav Khanna of the University of Rhode Island.

For instance, most time travel models require negative mass —and hence negative energy because, as Albert Einstein revealed when he discovered E = mc 2 , mass and energy are one and the same. In theory, at least, just as an electric charge can be positive or negative, so can mass—though no one’s ever found an example of negative mass. Why does time travel depend on such exotic matter? In many cases, it is needed to hold open a wormhole—a tunnel in spacetime predicted by general relativity that connects one point in the cosmos to another.

Without negative mass, gravity would cause this tunnel to collapse. “You can think of it as counteracting the positive mass or energy that wants to traverse the wormhole,” Goldberg says.

Khanna and Goldberg concur that it’s unlikely matter with negative mass even exists, although Khanna notes that some quantum phenomena show promise, for instance, for negative energy on very small scales. But that would be “nowhere close to the scale that would be needed” for a realistic time machine, he says.

These challenges explain why Khanna initially discouraged Caroline Mallary, then his graduate student at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, from doing a time travel project. Mallary and Khanna went forward anyway and came up with a theoretical time machine that didn’t require negative mass. In its simplistic form, Mallary’s idea involves two parallel cars, each made of regular matter. If you leave one parked and zoom the other with extreme acceleration, a closed timelike curve will form between them.

Easy, right? But while Mallary’s model gets rid of the need for negative matter, it adds another hurdle: it requires infinite density inside the cars for them to affect spacetime in a way that would be useful for time travel. Infinite density can be found inside a black hole, where gravity is so intense that it squishes matter into a mind-bogglingly small space called a singularity. In the model, each of the cars needs to contain such a singularity. “One of the reasons that there's not a lot of active research on this sort of thing is because of these constraints,” Mallary says.

Other researchers have created models of time travel that involve a wormhole, or a tunnel in spacetime from one point in the cosmos to another. “It's sort of a shortcut through the universe,” Goldberg says. Imagine accelerating one end of the wormhole to near the speed of light and then sending it back to where it came from. “Those two sides are no longer synced,” he says. “One is in the past; one is in the future.” Walk between them, and you’re time traveling.

You could accomplish something similar by moving one end of the wormhole near a big gravitational field—such as a black hole—while keeping the other end near a smaller gravitational force. In that way, time would slow down on the big gravity side, essentially allowing a particle or some other chunk of mass to reside in the past relative to the other side of the wormhole.

Making a wormhole requires pesky negative mass and energy, however. A wormhole created from normal mass would collapse because of gravity. “Most designs tend to have some similar sorts of issues,” Goldberg says. They’re theoretically possible, but there’s currently no feasible way to make them, kind of like a good-tasting pizza with no calories.

And maybe the problem is not just that we don’t know how to make time travel machines but also that it’s not possible to do so except on microscopic scales—a belief held by the late physicist Stephen Hawking. He proposed the chronology protection conjecture: The universe doesn’t allow time travel because it doesn’t allow alterations to the past. “It seems there is a chronology protection agency, which prevents the appearance of closed timelike curves and so makes the universe safe for historians,” Hawking wrote in a 1992 paper in Physical Review D .

Part of his reasoning involved the paradoxes time travel would create such as the aforementioned situation with a billiard ball and its more famous counterpart, the grandfather paradox : If you go back in time and kill your grandfather before he has children, you can’t be born, and therefore you can’t time travel, and therefore you couldn’t have killed your grandfather. And yet there you are.

Those complications are what interests Massachusetts Institute of Technology philosopher Agustin Rayo, however, because the paradoxes don’t just call causality and chronology into question. They also make free will seem suspect. If physics says you can go back in time, then why can’t you kill your grandfather? “What stops you?” he says. Are you not free?

Rayo suspects that time travel is consistent with free will, though. “What’s past is past,” he says. “So if, in fact, my grandfather survived long enough to have children, traveling back in time isn’t going to change that. Why will I fail if I try? I don’t know because I don’t have enough information about the past. What I do know is that I’ll fail somehow.”

If you went to kill your grandfather, in other words, you’d perhaps slip on a banana en route or miss the bus. “It's not like you would find some special force compelling you not to do it,” Costa says. “You would fail to do it for perfectly mundane reasons.”

In 2020 Costa worked with Germain Tobar, then his undergraduate student at the University of Queensland in Australia, on the math that would underlie a similar idea: that time travel is possible without paradoxes and with freedom of choice.

Goldberg agrees with them in a way. “I definitely fall into the category of [thinking that] if there is time travel, it will be constructed in such a way that it produces one self-consistent view of history,” he says. “Because that seems to be the way that all the rest of our physical laws are constructed.”

No one knows what the future of time travel to the past will hold. And so far, no time travelers have come to tell us about it.

Is Time Travel Possible?

We all travel in time! We travel one year in time between birthdays, for example. And we are all traveling in time at approximately the same speed: 1 second per second.

We typically experience time at one second per second. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

NASA's space telescopes also give us a way to look back in time. Telescopes help us see stars and galaxies that are very far away . It takes a long time for the light from faraway galaxies to reach us. So, when we look into the sky with a telescope, we are seeing what those stars and galaxies looked like a very long time ago.

However, when we think of the phrase "time travel," we are usually thinking of traveling faster than 1 second per second. That kind of time travel sounds like something you'd only see in movies or science fiction books. Could it be real? Science says yes!

This image from the Hubble Space Telescope shows galaxies that are very far away as they existed a very long time ago. Credit: NASA, ESA and R. Thompson (Univ. Arizona)

How do we know that time travel is possible?

More than 100 years ago, a famous scientist named Albert Einstein came up with an idea about how time works. He called it relativity. This theory says that time and space are linked together. Einstein also said our universe has a speed limit: nothing can travel faster than the speed of light (186,000 miles per second).

Einstein's theory of relativity says that space and time are linked together. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

What does this mean for time travel? Well, according to this theory, the faster you travel, the slower you experience time. Scientists have done some experiments to show that this is true.

For example, there was an experiment that used two clocks set to the exact same time. One clock stayed on Earth, while the other flew in an airplane (going in the same direction Earth rotates).

After the airplane flew around the world, scientists compared the two clocks. The clock on the fast-moving airplane was slightly behind the clock on the ground. So, the clock on the airplane was traveling slightly slower in time than 1 second per second.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Can we use time travel in everyday life?

We can't use a time machine to travel hundreds of years into the past or future. That kind of time travel only happens in books and movies. But the math of time travel does affect the things we use every day.

For example, we use GPS satellites to help us figure out how to get to new places. (Check out our video about how GPS satellites work .) NASA scientists also use a high-accuracy version of GPS to keep track of where satellites are in space. But did you know that GPS relies on time-travel calculations to help you get around town?

GPS satellites orbit around Earth very quickly at about 8,700 miles (14,000 kilometers) per hour. This slows down GPS satellite clocks by a small fraction of a second (similar to the airplane example above).

GPS satellites orbit around Earth at about 8,700 miles (14,000 kilometers) per hour. Credit: GPS.gov

However, the satellites are also orbiting Earth about 12,550 miles (20,200 km) above the surface. This actually speeds up GPS satellite clocks by a slighter larger fraction of a second.

Here's how: Einstein's theory also says that gravity curves space and time, causing the passage of time to slow down. High up where the satellites orbit, Earth's gravity is much weaker. This causes the clocks on GPS satellites to run faster than clocks on the ground.

The combined result is that the clocks on GPS satellites experience time at a rate slightly faster than 1 second per second. Luckily, scientists can use math to correct these differences in time.

If scientists didn't correct the GPS clocks, there would be big problems. GPS satellites wouldn't be able to correctly calculate their position or yours. The errors would add up to a few miles each day, which is a big deal. GPS maps might think your home is nowhere near where it actually is!

In Summary:

Yes, time travel is indeed a real thing. But it's not quite what you've probably seen in the movies. Under certain conditions, it is possible to experience time passing at a different rate than 1 second per second. And there are important reasons why we need to understand this real-world form of time travel.

If you liked this, you may like:

Can we time travel? A theoretical physicist provides some answers

Emeritus professor, Physics, Carleton University

Disclosure statement

Peter Watson received funding from NSERC. He is affiliated with Carleton University and a member of the Canadian Association of Physicists.

Carleton University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA.

Carleton University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

View all partners

- Bahasa Indonesia

Time travel makes regular appearances in popular culture, with innumerable time travel storylines in movies, television and literature. But it is a surprisingly old idea: one can argue that the Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex , written by Sophocles over 2,500 years ago, is the first time travel story .

But is time travel in fact possible? Given the popularity of the concept, this is a legitimate question. As a theoretical physicist, I find that there are several possible answers to this question, not all of which are contradictory.

The simplest answer is that time travel cannot be possible because if it was, we would already be doing it. One can argue that it is forbidden by the laws of physics, like the second law of thermodynamics or relativity . There are also technical challenges: it might be possible but would involve vast amounts of energy.

There is also the matter of time-travel paradoxes; we can — hypothetically — resolve these if free will is an illusion, if many worlds exist or if the past can only be witnessed but not experienced. Perhaps time travel is impossible simply because time must flow in a linear manner and we have no control over it, or perhaps time is an illusion and time travel is irrelevant.

Laws of physics

Since Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity — which describes the nature of time, space and gravity — is our most profound theory of time, we would like to think that time travel is forbidden by relativity. Unfortunately, one of his colleagues from the Institute for Advanced Study, Kurt Gödel, invented a universe in which time travel was not just possible, but the past and future were inextricably tangled.

We can actually design time machines , but most of these (in principle) successful proposals require negative energy , or negative mass, which does not seem to exist in our universe. If you drop a tennis ball of negative mass, it will fall upwards. This argument is rather unsatisfactory, since it explains why we cannot time travel in practice only by involving another idea — that of negative energy or mass — that we do not really understand.

Mathematical physicist Frank Tipler conceptualized a time machine that does not involve negative mass, but requires more energy than exists in the universe .

Time travel also violates the second law of thermodynamics , which states that entropy or randomness must always increase. Time can only move in one direction — in other words, you cannot unscramble an egg. More specifically, by travelling into the past we are going from now (a high entropy state) into the past, which must have lower entropy.

This argument originated with the English cosmologist Arthur Eddington , and is at best incomplete. Perhaps it stops you travelling into the past, but it says nothing about time travel into the future. In practice, it is just as hard for me to travel to next Thursday as it is to travel to last Thursday.

Resolving paradoxes

There is no doubt that if we could time travel freely, we run into the paradoxes. The best known is the “ grandfather paradox ”: one could hypothetically use a time machine to travel to the past and murder their grandfather before their father’s conception, thereby eliminating the possibility of their own birth. Logically, you cannot both exist and not exist.

Read more: Time travel could be possible, but only with parallel timelines

Kurt Vonnegut’s anti-war novel Slaughterhouse-Five , published in 1969, describes how to evade the grandfather paradox. If free will simply does not exist, it is not possible to kill one’s grandfather in the past, since he was not killed in the past. The novel’s protagonist, Billy Pilgrim, can only travel to other points on his world line (the timeline he exists in), but not to any other point in space-time, so he could not even contemplate killing his grandfather.

The universe in Slaughterhouse-Five is consistent with everything we know. The second law of thermodynamics works perfectly well within it and there is no conflict with relativity. But it is inconsistent with some things we believe in, like free will — you can observe the past, like watching a movie, but you cannot interfere with the actions of people in it.

Could we allow for actual modifications of the past, so that we could go back and murder our grandfather — or Hitler ? There are several multiverse theories that suppose that there are many timelines for different universes. This is also an old idea: in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol , Ebeneezer Scrooge experiences two alternative timelines, one of which leads to a shameful death and the other to happiness.

Time is a river

Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius wrote that:

“ Time is like a river made up of the events which happen , and a violent stream; for as soon as a thing has been seen, it is carried away, and another comes in its place, and this will be carried away too.”

We can imagine that time does flow past every point in the universe, like a river around a rock. But it is difficult to make the idea precise. A flow is a rate of change — the flow of a river is the amount of water that passes a specific length in a given time. Hence if time is a flow, it is at the rate of one second per second, which is not a very useful insight.

Theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking suggested that a “ chronology protection conjecture ” must exist, an as-yet-unknown physical principle that forbids time travel. Hawking’s concept originates from the idea that we cannot know what goes on inside a black hole, because we cannot get information out of it. But this argument is redundant: we cannot time travel because we cannot time travel!

Researchers are investigating a more fundamental theory, where time and space “emerge” from something else. This is referred to as quantum gravity , but unfortunately it does not exist yet.

So is time travel possible? Probably not, but we don’t know for sure!

- Time travel

- Stephen Hawking

- Albert Einstein

- Listen to this article

- Time travel paradox

- Arthur Eddington

Research Fellow – Magnetic Refrigeration

Centre Director, Transformative Media Technologies

Postdoctoral Research Fellowship

Social Media Producer

Dean (Head of School), Indigenous Knowledges

- Gameumentary

- Review in 3 Minutes

- Design Delve

- Extra Punctuation

- Zero Punctuation

- Area of Effect

- Escape the Law

- In the Frame

- New Narrative

- Out of Focus

- Slightly Something Else

- Escapist Staff

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Affiliate Policy

Time Travel Torts: How Law Gets Dicey When Dealing with Groundhog Day

Time travel is weird . We saw it in All You Zombies where the lead character became his own mother, father, lover, kidnapper, and bartender. We also saw it in Primer , which is seemingly impossible to understand, even after reading a book’s worth of flow charts , essays , and attempted explanations . What makes time travel so confusing is that it warps the laws of physics and requires us to revisit everything we thought we knew about the world.

But time travel doesn’t just warp the laws of physics — it warps the law itself. In the past, I’ve explained how time travel obliterates statutes of limitations and how the criminal justice system is powerless in the face of time travel murder. This week, I’m going to take it one step further to explain a legal time paradox — or how time travel can turn widely accepted legal principles on their head.

For the purposes of this article, I’ll be discussing instances in which time travelers have the ability to repeatedly travel back in time, to change the timeline based on previous time trips, and to observe the consequences of their actions. This would apply to the kinds of time travel seen in Groundhog Day , 11/22/63 , and Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time , but it would not apply to the time travel seen in The Terminator , A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court , or Avengers: Endgame .

Understanding the Legal Principles

There are two legal principles that are relevant to this analysis. The first principle is that the law does not require individuals to help strangers in need. For example, drivers are not required to help hitchhikers reach their destination, nor is a person required to call an ambulance if they see a person collapse. (I considered this rule in my previous column on transporter liability ). Instead, requirements to help others arise from preexisting relationships. To list just a few examples, parents have an obligation to help their children, doctors have an obligation to help their patients, and innkeepers have an obligation to protect their patrons. Generally speaking, in the absence of a special relationship, the only obligation one has is an obligation not to harm someone else. We can call this the Hippocratic principle. (Lawyers call it “duty.”)

The second principle is that, when it comes to avoiding harm, the law is concerned with predictability rather than personal responsibility. As an example, suppose Alice drives to a restaurant to pick up a carryout order. Alice doesn’t expect to be away from her car very long, so she leaves the keys in the ignition. While Alice is away, Bob steals her car, drives for a few blocks, and then collides with another driver. In several states, the law would hold Alice responsible for the damage caused by Bob — even though Alice did not steal a car and did not drive recklessly.

Why? Because (according to the courts) it is reasonably foreseeable that a thief would steal a readily available car and reasonably foreseeable that a thief would drive negligently in his efforts to flee. Thus, it was negligent of Alice to leave her keys in the car, and she can be held liable for any damage that would reasonably follow from that mistake.

In other words, the fact that the harm was imposed by another person is not as important as the fact that it was reasonably foreseeable that the harm would take place. We can call this the foreseeability principle. (Lawyers call it “proximate cause.”)

Applying Law to Time Travel (and Groundhog Day)

The Hippocratic principle and the foreseeability principle are well-established and can be applied consistently and (mostly) predictably. Time travel, though, changes everything.

What makes time travel special is that time travelers have access to more information than regular people — a time traveler can take an action, see how it plays out, and then, if the outcome is not desirable, go back and try again. Thus, in the world of a time traveler, the concept of “reasonable foreseeability” breaks down. There is no need for time travelers to balance risks or conduct a cost-benefit analysis, since any negative consequence or event can be reversed with the flip of a switch.

Groundhog Day shows us just how powerful this knowledge can be — Phil Connors was trapped in the same day for 10 years , and as he approached the end of the loop, he figured out how to prevent numerous deaths , enact the perfect bank robbery , and seduce 90% of women in the town , among other things. A person in that kind of situation would have perfect knowledge — virtually any action would have known and certain consequences, and a time traveler would know how each and every action would impact — for better or worse — those around him.

This means that a time traveler could be held responsible for all of the consequences of his actions, regardless of how attenuated those consequences are from the underlying action. As a simple example, consider a scenario in which Phil greets Alice on a street corner. Because of the brief conversation, Alice is delayed by a few seconds in her commute to work and as a result gets run over by careless driver Bob. If Alice had not spoken with Phil, she would have avoided Bob entirely.

In the normal world, we would say that Bob is entirely to blame. But if Phil is in a time loop, then he would know that his conversation would lead to Alice’s death and could avoid it in future loops. Thus, as far as Phil is concerned, talking with Alice is a reasonably foreseeable cause of her death — even though, from the perspective of everyone else, the consequence seems completely divorced from the underlying action.

Time travel also poses a problem for the Hippocratic principle. The “do not harm others” principle presupposes the existence of a baseline status, as if to say, “You have an obligation not to act in a way that would harm a person, as measured relative to the person’s status in the absence of your action.” Time travel throws that baseline status into question.

Suppose that during the first course of events (i.e., in the first day of the time loop), Phil takes an action that causes (through some chain of events) Alice to avoid an injury. In time loop B, Phil knows that through his actions in the “normal” course of events, Alice would have avoided an injury. Thus, in a sense, Phil knows that he will cause her injury if he does not take the action. Put differently, time travel raises the question of which timeline should be used to measure someone’s baseline status (i.e., which timeline you should use to figure out whether your actions have harmed another). A few potential answers come to mind:

- What the timeline would look like without the time traveler.

- What the timeline looked like after the first iteration.

- Evaluate each iteration independently, according to the normal rules.

- The best timeline for each person.

It is not easy to choose between those (or any other) options. This is similar to the problem we encountered when considering time annihilation as a crime — when a time traveler has the ability to switch at will between one timeline and another, there is no principled basis to favor one timeline over another. Here, however, the problem is more challenging, since a time traveler’s complete mastery over events means that a time traveler is responsible for everything that happens — and does not happen — in a particular timeline. In other words, a time traveler is responsible for all events, because a time traveler controls all events (provided that the time traveler has the ability to impact those events in at least one of the infinite potential timelines).

Or, put differently, when time travelers enter their last time loop, they necessarily decide — through their actions — which of an infinite number of timelines to enact. In this way, time travelers can be said to have caused any harm or injury experienced in their chosen timeline. In this sense, one could argue that, in a world of time travel (and particularly time loop time travel), one’s obligation not to harm others amounts to an obligation to help others avoid harm, since any decision not to avoid harm would be equivalent to a decision to impose that harm.

So far, my consideration of time travel has been limited to the Groundhog Day scenario — a time loop with countless iterations that does not take a physical toll on the time traveler from loop to loop. The analysis applies just as much to less extreme scenarios, but the implications of the analysis will not be as severe.

For example, time travelers with only three iterations of a time loop will have a much better understanding of how their actions affect others relative to non-time travelers — but their knowledge will not be anywhere near as developed as an infinite time-looper. Thus, three-loop time travelers can be held to a higher standard of “reasonable foreseeability” than an average person, but they cannot be held to the same standard as a Phil Connors-like time traveler. In essence, the less knowledge a time traveler has about the consequences of their actions, the less responsible they are for those consequences.

Likewise, in a scenario with just a few iterations, the overall state of the timeline would still be outside of the time traveler’s control, so the Hippocratic principle would mostly apply in the same way as it does in a world without time travel. (Of course, the more timelines a time traveler has to choose from, the stronger the argument that the traveler’s selection of a timeline amounts to a decision to impose the harm in that timeline.) The specifics of the scenarios and of one’s legal obligations will vary based on the number of time jumps, the physical toll of those jumps on the time traveler, the cognitive abilities of the time traveler, and the duration of the time window (that is, repeating a day is much different than repeating a lifetime).

Again — time travel is weird . It leads to unanticipated consequences and counterintuitive results. But law is also weird and also leads to unanticipated consequences and counterintuitive results. In 1995, a man was sentenced to life in prison for stealing a piece of pizza; Brian Dement is serving a life sentence in prison, despite the fact that DNA evidence conclusively proves he is innocent; police think that saggy pants create probable cause for a search. The list goes on.

It stands to reason that when you cross the streams of time travel and law, “You’re going to see some serious shit .” And that’s exactly what we’ve seen — for time travelers, the rule that says you can only be held responsible for the foreseeable would hold time travelers responsible for everything . The rule that says you have no obligation to help strangers says that time travelers must help strangers.

On one hand, these rules are fantastic — it shows that a hypothetical era of time travel would usher in a new age of moral responsibility and high moral character. On the other hand, for people like me who dream of time travel, these new rules provide yet another obstacle on the road to time mastery. People often wonder: If time travel exists, why haven’t we seen any time travelers yet? Now we know the answer: The legal fees and liability associated with time travel are just too high — not even the most adventurous of explorers would dare risk that kind of legal exposure.

Plus.Maths.org

Is time travel allowed?

In brief: The laws of physics allow members of an exceedingly advanced civilisation to travel forward in time as fast as they might wish. Backward time travel is another matter; we do not know whether it is allowed by the laws of physics, and the answer is likely controlled by a set of physical laws that we do not yet understand at all well: the laws of quantum gravity. In order for humans to travel forward in time very rapidly, or backward (if allowed at all), we would need technology far far beyond anything we are capable of today.

Travelling forward in time rapidly

Albert Einstein's relativistic laws of physics tell us that time is "personal". If you and I move differently or are at different locations in a gravitational field , then the rate of flow of time that you experience (the rate that governs the ticking of any very good clock you carry with you and that governs the aging of your body) is different from the rate of time flow that I experience. (Einstein used the phrase "time is relative"; I prefer "time is personal".)

Example of Twins Paradox

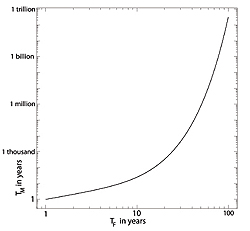

Florence rides in a space ship that accelerates outward from Earth on a straight line with one Earth gravity of acceleration, $g=9.81 m/s^2$ for a time $T_F/4$ (as measured by her), then decelerates at $g$ for a time $T_F/4$, winding up at rest relative to Earth but very far away. Florence then accelerates back toward Earth at $g$ for a time $T_F/4$ and decelerates at $g$ for $T_F/4$, winding up at rest on Earth. When the trip is finished and Florence meets her Earth-bound twin Metheuselah, she has aged by $T_F$ while he has aged by a larger amount, $T_M$. A fairly simple calculation (see [7] ) using the laws of special relativity gives the following expression for Methuselah's aging in terms of Florence's: $$T_M = (2 c/g) [exp(gT_F/4c)- exp(-gT_F/4c)].$$ Here $exp(x) = e^x$ is the exponential function and $c$ is the speed of light (about 299.8 million m/s). This relationship is plotted in the following figure:

Click here for a larger version of the graph.

If Florence's clocks and aging report a round trip time of 10 years, Methuselah will have aged by 25 years. If Florence aged 30 years, Methuselah will have aged 4,500 years. If Florence aged 88 years, Methuselah will have aged 14 billion years, which is the current age of our Universe! Unfortunately, no known rocket fuel, not even thermonuclear fusion, is capable of producing the sustained multi-year-long acceleration required for such a trip.

This personal character of time allows one person to travel forward in time much faster than another, a phenomenon embodied in the so-called twins paradox . One twin (call him Methuselah) stays at home on Earth; the other (Florence) travels out into the Universe at high speed and then returns. When they meet at the end of the trip, Florence will have aged far less than Methuselah; for example, Florence may have aged 30 years and Methuselah 4,500 years. (The twin that ages least is the one who undergoes huge accelerations, to get up to high speed, slow down, reverse direction, then accelerate back and slow to a halt on Earth. The twin who leads the sedate life ages the most.)

A massive black hole is another vehicle for rapid forward time travel: If Methuselah remains in orbit high above the event horizon of a massive black hole (say, one whose gravitational pull is that of a billion suns) and Florence travels down to near the event horizon and hovers just above it for, say, 30 years and then returns, Methuselah can have aged thousands or millions of years. This is because time flows much more slowly near a black hole's event horizon (where the acceleration of gravity is huge) than far above it (where one can live sedately).

These time travel phenomena have been tested in the laboratory. Muons — short-lived elementary particles — travelling around and around in a storage ring at 0.9994 of the speed of light, at the Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island, New York, have been seen to age 29 times more slowly than muons at rest in the laboratory. And atomic clocks on the surface of the Earth have been seen to run more slowly than atomic clocks high above the Earth's surface — more slowly by about 4 parts in 10 billion.

Travelling backward in time: chronology protection

We physicists have been working hard since the late 1980s to understand whether the laws of physics allow backward time travel. We do not have a definitive answer yet, but the likely answer has been summarised by Stephen Hawking, in his Chronology Protection Conjecture (see [1] ): The laws of physics always conspire to prevent anything from travelling backward in time, thereby keeping the Universe safe for historians.

We physicists have identified two mechanisms that might protect chronology: (1) The exotic material that is required in the manufacture of any time machine might be forbidden to exist, by the laws of physics — forbidden to exist in the large amounts that time machines always require. (2) Time machines might always self-destruct, explosively, when one tries to activate them.

These mechanisms (1) and (2) are descriptive translations of mathematical results that we physicists have derived using the laws of physics expressed in their own natural language: mathematics. The sentences (1) and (2) capture the essence of our calculations, but crucial details are lost in translation. For anyone who wishes to struggle to understand those details, good places to start are a recent beautiful but highly technical review article by John Friedman (see [2] ), and a much less technical but older and slightly outdated article by Matt Visser (see [3] ).

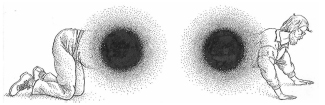

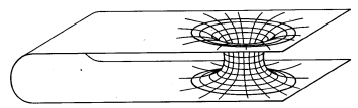

I shall illustrate these chronology-protection mechanisms by an example of a time machine that my students Mike Morris and Ulvi Yurtsever and I invented and explored mathematically in 1989: a time machine based on wormholes. (This is just one of many time-machine designs that have been studied. For others see Visser's review, [3] )

Me crawling through a wormhole whose length is only a few centimetres but circumference is about that of my belly. (From my book Black Holes and Time Warps , [4] , where you can find a more detailed description of this time machine.)

A wormhole-based time machine: A wormhole is a hypothetical tunnel through hyperspace that links one place in our Universe (e.g. my office at Caltech) to another place (e.g. the Caltech football field). Each end of the wormhole (each mouth ) looks like a crystal ball. Staring into it, one sees a distorted image of objects at the other end. Looking into the mouth in my office, I see the football field, distorted; someone on the football field, looking into the mouth there, sees me and my office, distorted. The wormhole (tunnel) might be only 3 metres long, so if I enter the mouth in my office and then travel just 3 metres through the tunnel, I emerge from the other mouth, onto the football field 300 metres from my office.

A wormhole as viewed from a higher-dimensional hyperspace. Our Universe is the two-dimensional sheet. The wormhole is a short cut through hyperspace from one location in our sheet (our Universe) to another.

Suppose, now, that a creature from an extremely advanced civilisation carries the football-field mouth out into the Universe on a "twins paradox" trip. When that mouth returns, it may have aged by only one second while the mouth in my office aged by one day. The wormhole has become a time machine: If I enter one mouth and travel through it for only a few seconds, I emerge from the other mouth one day in the future. Travelling through it in the other direction, I emerge one day in the past! (See [4] .)

Exotic Matter and Vacuum Fluctuations: We do not know whether the laws of physics permit wormholes. We do know, however, that a wormhole will implode so quickly that nothing can traverse it, unless it is held open by gravitationally repulsive forces that can only be produced by exotic matter. By the phrase "exotic matter" I mean matter that has negative energy and therefore anti-gravitates, i.e. repels.

The quantum laws of physics do permit exotic matter to exist, and it has been created in the laboratory in very tiny amounts: in the so-called Casimir vacuum between two electrically conducting plates, and in the so-called squeezed vacuum that is generated by optical physicists using nonlinear crystals.

The key to this negative energy is the fact that empty space (the vacuum ) is filled with tiny fluctuations of all kinds of matter and fields that exist in the Universe. It is impossible to make these fluctuations go away. They are a consequence of the quantum mechanical uncertainty principle : if, at one moment of time, there are no fluctuations at all of (for example) the electromagnetic field, then the rate of change of the fluctuations must be infinitely large and a moment later the fluctuations will be enormous. The product of the strength of the fluctuations and the magnitude of their rate of change is always bigger than a certain limit, given by the uncertainty principle. As a result, fluctuations are always present. We call them vacuum fluctuations because they are a property of the vacuum, i.e. of otherwise empty space.

The laws of quantum physics say that vacuum fluctuations produce no gravity — or perhaps only an exceedingly tiny amount of gravity: the gravity that is accelerating the expansion of the Universe. In other words vacuum fluctuations may be responsible for the so-called cosmological dark energy . But that dark energy is so tiny (10 -121 in dimensionless numbers ) that it is irrelevant for my discussion of time machines; so I shall say that the quantum fluctuations produce no gravity at all.

Or, rather, they produce no gravity under normal circumstances. One can devise ways, in fact, to make one region of empty space lend some of its vacuum fluctuations to an adjacent region. (This is what experimental physicists do with the Casimir vacuum and with the squeezed vacuum.) When this happens, the lending region is left with a negative amount of gravitating energy, and the borrowing region gets positive gravitating energy. The quantum laws place tight constraints on the amount of fluctuational energy that can be loaned. The larger the size of the lending region, the less energy it can loan and therefore the less negative its energy can become. This is true in the Casimir vacuum, in the squeezed vacuum, and in all other variants of exotic matter. The laws of physics dictate it.

These constraints on the amount of negative gravitating energy might be severe enough to prevent one from ever accumulating enough of it to prevent a wormhole from imploding (see [5] ). The reason is that regions of space which do the borrowing and the devices which catalyse the borrowing might always have so much positive energy of their own, that their attractive gravity counteracts the negative energy's repulsive gravity, and triggers all wormholes to implode. If that is the case, then wormhole-based time machines are forbidden: one can never travel through a wormhole before it implodes. (John Friedman and colleagues have called this topological censorship , see [2] .)

My personal guess is that these constraints on exotic matter do not prevent wormholes from being held open and thus do not protect chronology, but I could well turn out to be wrong. To learn the truth, we physicists must develop a deeper understanding of quantum theory in warped spacetime than we now have — i.e. a deeper understanding of the combined laws of quantum theory and general relativity, the laws of quantum gravity.

Time machine self destruction: If it turns out that wormholes can be held open, then doing so is not enough to guarantee that an ultra-advanced civilisation can convert a wormhole into a time machine via a twins-paradox trip (carrying one mouth out into the Universe at high speed and then back). There is a second obstacle that must be surmounted — time machine self destruction:

Time machine self destruction: As the right wormhole flies back toward the left, at the end of its twins-paradox trip, vacuum fluctuations flow through the wormhole then out through the space between them, returning to their starting point at the moment they left. Their gravitating energy grows extremely large, and perhaps destroys the wormhole at the moment it becomes a time machine. (Figure adapted from my book Black Holes and Time Warps , [4] .)

As the travelling mouth is returning to Earth, there comes a first moment when its wormhole can be used to travel backward in time. The first thing that can do so, and thereby meet itself before it left, is an entity that enters one mouth, exits from the other before it entered, and then flies through the Universe back to its starting point at the highest possible speed, the speed of light — arriving back at the first mouth at precisely the moment it started its trip. Even if no light or other light-speed radiation travels on this round-trip time-travel route, vacuum fluctuations will always do so. They cannot be stopped. Upon arriving back at their starting point at the very moment when they left, the vacuum fluctuations will pile up on top of their younger selves. The result is a duplicate of every fluctuation, and then, with another round trip, a quadrupling of every fluctuation, and so forth. The bottom line, according to a calculation that I did with my postdoc Sung-Won Kim in 1990, is an explosive flow of gravitating fluctuational energy through the wormhole at precisely the moment when time travel is first possible — at the moment of time machine activation [4] .

Will this explosive fluctuational energy destroy the wormhole and thence the time machine? At first Kim and I thought the wormhole could survive. However Stephen Hawking gave strong arguments to the contrary, in his seminal 1991 research paper on chronology protection. The explosion is very likely to destroy the time machine when it is first activated, Hawking argued — and not just this time machine, but any time machine that even the most advanced civilisation might conceive and build. Over the next few years many other physicists weighed in, with analyses of other time machine designs, and it began to look like Hawking might be wrong: a sufficiently clever design might protect a time machine from self destruction. Then in 1996 Bernard Kay, Marek Radzikowski and Robert Wald developed a powerful mathematical proof that the version of the laws of quantum physics which we were all using to analyse time machine self destruction are incapable of revealing the explosion's outcome. The outcome is held tightly in the grip of the laws of quantum gravity, which we do not yet understand fully.

The fate of any time machine?

Hawking and I have a long history of bets with each other, about unsolved mysteries in physics. But we are not making a bet on this one, since for once we are on the same side. When we physicists have mastered the laws of quantum gravity (Hawking and I agree), we will very likely discover that chronology is protected: the explosion always does destroy any time machine, when it is first activated.

In June 2000, on the occasion of my 60th birthday, Hawking presented me with a tentative analysis of the explosion's outcome, using his own tentative version of the laws of quantum gravity. His conclusion: if I try to use a very advanced civilisation's wormhole to travel backward in time, the quantum mechanical probability that I will succeed is one part in 10 60 ; see Hawking's article in my birthday party book, [6] . That's an awfully small probability of surviving the explosion. Given the opportunity to try, I would not take the risk.

Other time machines: It is amazing what we can learn from the laws of physics, when we understand them well. One famous example is the laws' absolutely firm insistence that it is impossible to construct a perpetual motion machine, even if one has all the tools of an exceedingly advanced civilisation. Another example is a proof by Hawking that to make a time machine, no matter how one goes about it, one must use exotic matter — matter with negative energy — as an integral part of the device; wormholes illustrate this, but it is true in general. And a third example is the proof by Kay, Radzikovsky and Wald that the laws of physics as we now know them will break down whenever a time machine is activated, no matter how one designs the machine. Again wormholes are just one example. Hawking's theorem, and that of Kay, Radzikovsky and Wald, tell us that the fates of all time machines are held tightly in the grip of the laws of quantum gravity.

Progress in the quest to understand quantum gravity has been substantial over the past two decades. Complete success will come, I am convinced, within the next two decades or so — and it will bring not only a clear understanding of whether backward time travel is possible, but also an understanding of many other mysteries, including how our Universe was born (see the Plus article What happened before the Big Bang?).

- Add new comment

Ray said...

I know a little GR; but no Quantum Gravity and very little QM. I interpret the article as saying that the consensus is: Quantum Gravity can not be fit into Godel's time-closed solution to GR. Is that correct? In that case the global topology would constrain the deeper theories. Put another way Quantum Mechanics can not be embedded/formulated on an arbitrary manifold. These are questions; not statements. Ray

Quantum_Flux said...

It is the same thing for observer 1 to rapidly travel into the past as it is for observer 2 to rapidly travel into the future.

@Quantum_Flux: always travelling to the future...

"It is the same thing for observer 1 to rapidly travel into the past as it is for observer 2 to rapidly travel into the future."

No, it is not. Going back in time would imply that the time order of the meetings as seen by observer 2 is the reverse of the meetings order as seen by observer 1. As presently "understood", if meeting 2 is later than meeting 1 for one observer then it will also be later for the other observer.

I read references 2,3 3 is quite readable. 2 is tougher and I am not through. The idea that some local properties can't be extended globally in some topologies is not as strange as it might seem at first glance; there are other examples. I do have doubts about some of the reasoning; but that doesn't fault the reasoning just the presumptions. I think its possible that the "energy conditions" are not the right analysis tool. Something along the lines of Entropy (Maxwell's daemon ) might be sharper in the mathematical sense. Ray

The Grin Reaper said...

Th relation to Casimir vacuums was fascinating. So is the solidarity of Hawking's argument. Although the possibilities of time travel would lead to the age old grandfather paradox, and I am not sure as to what would be a right explanation. Maybe the Copenhagen interpretation of splitting states to maintain Quantum decoherence. Cannot say anything conclusively.

The Possibility of Time Travel

If you understood the cause of Gravity, then you would know that time travel is possible as I do. Jump off a building or out of an aeroplane and you don't need fuel to accelerate. Simply creating a G-field in front of a craft would cause the craft to 'fall' towards that field which would in turn be projected further ahead causing an exponential acceleration curve up to and far exceeding the speed of light. One must also realize that only one half of any trip could be accelerated towards and the remainder must be decelerated in the opposite direction to arrive at the destinations relative speed.

The Possibility of Flawed Logic

It looks like somebody doesn't understand relativity. Our current understanding of physics dictates that we cannot travel faster than the speed of light. Even with an extremely fast acceleration, from at least one reference frame, if an object has mass, it will never reach the speed of light. Accelerating an object with a mass's speed to the speed of light would require an infinite (read: extremely massive) amount of energy that we just aren't capable of producing. Sure putting a gravitational field in front of an object would produce a force, but just how massive would would the object have to be to produce a gravitational field that produces enough force to actually accomplish something within a limited amount of time? It would appear that the only hypothetically feasible object to use would be a black hole, and even those are not known well enough to do anything useful with them. It's useless talking about how we are going to accomplish time-travel if we don't even have all of the (mathematical) tools available to evaluate the situation.

Is Time-travel allowed?

Time-travel is not possible for the good reason that time does not exist, so I would answer no(!) if someone asked me that question. Please refer to http://www.spacetime.nu Brgds! Bo Nyberg

A very clear and enjoyable

A very clear and enjoyable article. Thanks. - Neal Asher

early entry into quantum physics

I am a student in 12th grade. I really do not have the mathematical advantage nor the complete skills related to quantum physics, but yes timetravel and quantum gravity is something I am immensely interested in and have been reading about this for a very long time. I found this article very interesting and it has left me wondering what would be going on in the mind of "physics" when it came into existence. Why will it not want us to do something and why permit something else. And if the laws of physics break down, and maybe if I am the one who's behind it, wont I have the freedom to make new laws of my own which permit time travel? Its like I find a way to break something to the ground and build it up again as per my fancy? And well, I have been going through a few books on quantum physics and I would love it if someone can suggest a book on mathematics which will help supplement my present reading. thanks!!!

Time seems not to be proven here, just assumed

A very interesting article but I have to politely disagree. Firstly because no proof of times existence is given or referred to. Specifically no proof is given that as things move change and interact, a thing called time needs to exist, or 'passes'.

From the outset the suggestion "The laws of physics allow members of an exceedingly advanced civilisation to travel forward in time as fast as they might wish." May be seriously flawed.

Relativity, as in GPS systems for example, does indeed show that fast moving objects 'change' more slowly. And as they do so it can be said the surrounding matter effectively changes more quickly. Thus a fast moving astronaut might return to earth finding it very different than might be expected. But unless proof is given that time, and 'the future' actually exist, all this proves is that matter exists, moves, changes and interacts 'now' -at different rates under different conditions. And not, IMO, that time, the future, or time travel may exist.

(Note, in 'electrodynamics' Einstein only -states- that a rotating hand on a numbered dial (a 'watch') shows the existence and passing of a thing called time. But logically, no matter how many people assume this is correct, without actual, scientific, experimental proof, all such a device shows is that motors can rotate hands. And thus SR only shows that moving motors etc run more slowly than (relatively) stationary ones).

M.Marsden (Auth-A Brief history of Timelessness )

i think worm hole 'time travel' can be deconstructed Timelessly

In this article the wormhole is suggested as a possible time travel device. The only problems suggested being that exotic matter would be required, or it might necessarily self destruct re the laws of physics. i.e be practically impossible.

but unless it is proven that there is indeed a past and/or future then perhaps Relatvity just shows how matter might be warped, stretched, and dilated in its rates of change - but not over a thing called time.

If this is the case then the worm hole 'billiard ball' paradox (for example) can be explained 'timelessly', thus...

Time travel, Worm hole, billiard ball' paradox, Timelessly. (re Paul Davies- New scientist article) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wc5cRGOGIEU

Matthew Marsden

Time is indeed a cultural construct. This is in part demonstrated by differing notions of time in different cultures.

Part of the strength of modern physics is that it has allowed useful mathematical calculation of some of what is entailed in passing through a wormhole. Part of the challenge is that this infrastructure provides restrictive overhead for properly understanding and moving toward a deeper knowledge. One obvious example for both of these comments is the apparent requirement of a physical process for creating a time travel machine, and for keeping the wormhole open.

The actual resolution of this matter may emerge from use of different mathematics and innovative experimental procedures. An attitude of open inquiry will be very important. Some time ago, as a graduate student in physics, I posited to a leading physicist at MIT that there might be two dimensions to time, or that time might behave differently than we think it does. He was outraged, and the conversation ended there, but now Kip Thorne and colleagues have done some of the work implied. So my hat is off to them. I think significant answers are just around the corner, and it will take considerable meticulous effort to get there.

Kip Thorne's work in the area has come a long way in very few years.

John Carlton-Foss

Time.University

I recently purchased two websites Spacetime.University and Time.University which I plan to post content related to Spacetime and Quantum Time mathematics. For now most of my tutorials etc are on the website Spacetime.University. I am a big fan of Kipe Thorn's ideas. Some of Kip Thorne's ideas get a mention. Any feedback is appreciated.

My project is very new so any suggestions such as websites to link to or comment on content would be appreciated.

We are all time travellers as time is just a measure of the rate at which the universe is running down, i.e. increasing entropy, so is always in that direction.

If time travel was allowed in the reverse direction then we would need to send an observer back to experience it as such. Unfortunately this would also mean that, as far as this observer is concerned, it would have to put the WHOLE of the universe, i.e. every particle, each and every one in its original position and each with its original momentum and ground energy as they were back at the time the observer makes the journey INCLUDING the particles that make up the observer! This might be the reason for the observer (the time machine) vanishing in a violent explosion as its constituent parts tear of to their various origins at that distant time and place.

I am well aware that I am missing the theoretical knowledge and the mathematics to describe what the above words mean but I am pretty sure this is the way it works no matter how many mathematical fuddles are used to get over this simple concept of why we cannot fight the whole of the universe and the universal increase in entropy as we are part of it and cannot stand apart from it such a way that we are not torn to shreds as our atoms are dispersed through time and space to regain their positions at the time we seek to visit. This is what it really means to go back in time to a universe as it was, back then. If you had at your disposal a universe full of energy, the knowledge about all its constituent particles, and the wit to control all of this, then you might, just, have a chance.

OR, am I missing something?

I am also aware, as are others in the earlier comments, that what we called time is not a real thing it is just the measure of the rate of change of entropy which we also know can vary, relatively, in the forward direction simply by accelerating, relative, to another body such that our rate of change of time is different to the body that is not accelerated. Time appears to be a construct of the mind to enable us to comprehend change and exchange ideas about such change in much the same way as we agree about colours as we can never be certain that the colours we perceive are the same as those perceived by others. Time also flows differently according to mood which also seems to suggest it is a construct of the mind and not a real phenomenon.

There have been designs for interstellar ram-jets that collect hydrogen nuclei using huge electrostatic collector/compressors to fuse these together to make heavier nuclei which they expel out of the back at very near the speed of light thus propelling the ship at, say, a constant 1g using the energy from the, free, interstellar hydrogen fuel. This, if perfected, could make the Nebulae in Andromeda about a lifetime away for the travellers but about 2.5million years, each way, for those living on Earth. There is, of course, the ablation and radiation due to the extremely high energy particle flux (blue shifted, to overcome - maybe we would have to convert a trillion tonne asteroid into a spaceship - or, just maybe, it is all just a pipedream! In any case this is still time travel into the future, not the past.

I would be very much obliged for a critique on the above ideas as I have long (50 years or more) wondered why I have not seen this idea posited anywhere else as it seems such a reasonable rebuttal to the question of the possibility of time travel into the past.

John Barton Wood

Leeds, West Yorkshire

Time travel

As long as we continue to think of the 'arrow of time' time travel will not be achieved, at least not in the sense we wish. For Time Travel proper, Time itself must exist as a genuine entity as does does Space and therefore have separate dimensions of its own.

The Ethics and Morals of Time Travel: Tackling the Time Traveler’s Dilemma

The ethical and moral implications of time travel are complex and multi-layered. In recent years, discussions about the feasibility of time travel have become more prevalent, leading to questions about whether or not it would be ethical to travel through time.

Many experts argue that traveling through time could have far-reaching implications, such as altering the course of history, causing paradoxes, and creating significant ethical dilemmas. Some argue that time travel could allow for the correction of past injustices, while others argue that it could create new ones.

Ultimately, the question of whether time travel is ethical depends on a variety of factors, including the reason for time travel, its potential consequences, and the impact it could have on individuals and society as a whole.

Credit: www.leisurebyte.com

The Concept Of Altering The Past

The concept of time travel has been a source of fascination for humankind for as long as we have dreamt about our future. With the advent of technology and modern science, the idea of traveling through time is gradually moving from the realm of science fiction to scientific possibility.

Altering past events may seem intriguing at first glance, but it raises significant ethical and moral dilemmas. Here are some points to keep in mind when considering the idea of changing past events:

The Butterfly Effect And Its Consequences

The butterfly effect is a concept that suggests that small changes in a complex system can have significant and unpredictable effects. In the context of time travel, this concept takes a whole new meaning. Even the slightest alteration of a past event can have an enormous impact on future events, causing unexpected and potentially dangerous consequences.

For instance, what if someone went back in time and prevented the birth of a famous inventor, such as thomas edison or steve jobs? The world, as we know it, could be vastly different, or may not even exist at all.

The consequence of the butterfly effect is not limited to the advancement of technology or history. It could also result in the loss of life, cultural changes, or the destruction of the environment. Consider the outcome if someone went back in time and killed adolf hitler before he gained power.

While it may seem like a noble act, would it fundamentally change the philosophies that fueled the nazi party? Would that same person be responsible for creating another dictator in the future? The butterfly effect raises more questions than answers, and we may never be able to predict the outcomes of our actions when we meddle with time travel.

Analysis Of The Effect Of Altering Historical Events On Society, Culture, And Moral Values

An action as seemingly innocuous as going back in time to buy a particular painting or artifact could have a profoundly negative impact on society, culture, and moral values. Imagine someone traveled back in time and took the mona lisa from the louvre in the 19th century.

While it could significantly benefit one individual, it would rob the world of a masterpiece that is enjoyed and celebrated for its beauty and cultural significance. Additionally, hypothetically speaking, if someone went back in time and saved john f. kennedy from assassination, it could set a dangerous precedent of altering historical events that changed the trajectory of our culture and values.

The Paradoxical Nature Of Changing The Past And The Resulting Confusion And Chaos

The idea of time travel inherently creates a paradox, as the ability to change the past undermines the very essence of time itself. If someone went back in time and killed their grandfather, what would happen to their existence? Would they cease to exist, or would they have created a different universe entirely?

This paradox and uncertainty surrounding the idea of time travel can lead to a world of confusion and chaos.

The concept of changing the past presents a host of ethical and moral dilemmas, including the butterfly effect, the impact of changing historical events on society and culture, and the resulting paradoxical nature of changing the past. While it may be tempting to correct our mistakes or improve our future, we may need to make peace with the fact that time is a one-way street, and changing it would bring more unknown and unintended risks than rewards.

The Responsibility Of Time Travelers

Analyzing the responsibility that time travelers bear for the consequences of their actions.

The very notion of time travel brings up several moral and ethical dilemmas that we as a society must address. One such dilemma involves analyzing the responsibility that time travelers bear for the consequences of their actions. Here are some key points to consider:

- Time travelers must recognize the impact of their actions on the course of history. Any significant deviation from the timeline can have catastrophic consequences in the present and future.

- Time travelers have a responsibility to ensure that they do not disrupt the course of natural events in a way that could cause harm to future generations.

- Time travelers must consider the implications of their actions on future generations and act accordingly to minimize negative outcomes.

- Time travelers must be prepared to accept responsibility for their actions and the consequences that may arise from them.

The Moral And Ethical Considerations Of Using Knowledge Gained From The Future For Personal Gain