What was the Grand Tour?

Find out about the travel phenomenon that became popular amongst the young nobility of England

Art, antiquity and architecture: the Grand Tour provided an opportunity to discover the cultural wonders of Europe and beyond.

Popular throughout the 18th century, this extended journey was seen as a rite of passage for mainly young, aristocratic English men.

As well as marvelling at artistic masterpieces, Grand Tourists brought back souvenirs to commemorate and display their journeys at home.

One exceptional example forms the subject of a new exhibition at the National Maritime Museum. Canaletto’s Venice Revisited brings together 24 of Canaletto’s Venetian views, commissioned in 1731 by Lord John Russell following his visit to Venice.

Find out more about this travel phenomenon – and uncover its rich cultural legacy.

Canaletto's Venice Revisited

The origins of the Grand Tour

The development of the Grand Tour dates back to the 16th century.

One of the earliest Grand Tourists was the architect Inigo Jones , who embarked on a tour of Italy in 1613-14 with his patron Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel.

Jones visited cities such as Parma, Venice and Rome. However, it was Naples that proved the high point of his travels.

Jones was particularly fascinated by the San Paolo Maggiore, describing the church as “one of the best things that I have ever seen.”

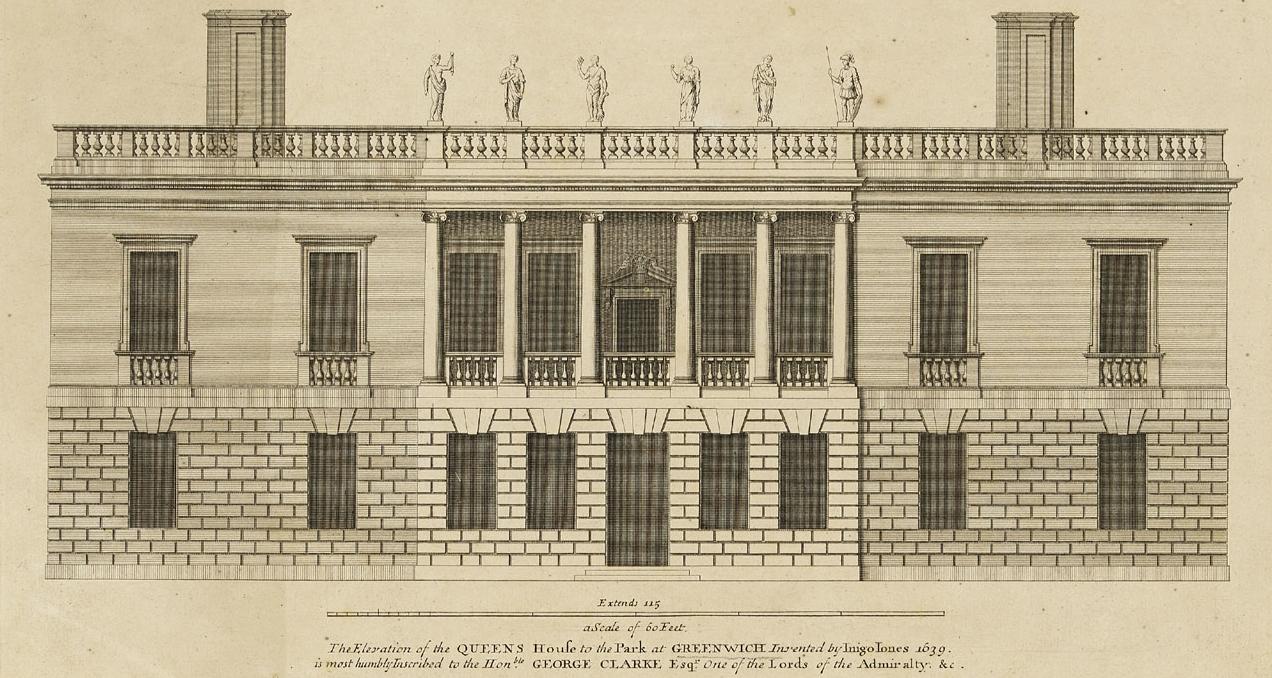

Jones’s time in Italy shaped his architectural style. In 1616, Jones was commissioned to design the Queen’s House in Greenwich for Queen Anne of Denmark , the wife of King James I. Completed in around 1636, the house was the first classical building in England.

The expression ‘Grand Tour’ itself comes from 17th century travel writer and Roman Catholic priest Richard Lassels, who used it in his guidebook The Voyage of Italy, published in 1670.

By the 18th century, the Grand Tour had reached its zenith. Despite Anglo-French wars in 1689-97 and 1702-13, this was a time of relative stability in Europe, which made travelling across the continent easier.

The Grand Tour route

For young English aristocrats, embarking on the Grand Tour was seen as an important rite of passage.

Accompanied by a tutor, a Grand Tourist’s route typically involved taking a ship across the English Channel before travelling in a carriage through France, stopping at Paris and other major cities.

Italy was also a popular destination thanks to the art and architecture of places such as Venice, Florence, Rome, Milan and Naples. More adventurous travellers ventured to Sicily or even sailed across to Greece. The average Grand Tour lasted for at least a year.

As Katherine Gazzard, Curator of Art at Royal Museums Greenwich explains, this extended journey marked the culmination of a Grand Tourist’s education.

“The Grand Tourists would have received an education that was grounded in the Classics,” she says. “During their travels to the continent, they would have seen classical ruins and read Latin and Greek texts. The Grand Tour was also an opportunity to take in more recent culture, such as Renaissance paintings, and see contemporary artists at work.”

As well as educational opportunities, the Grand Tour was linked with independence. Places such as Venice were popular with pleasure seekers, boasting gambling houses and occasions for drinking and partying.

“On the Grand Tour, there’s a sense that travellers are gaining some of their independence and having a lesson in the ways of the world,” Gazzard explains. “For visitors to Venice, there were opportunities to behave beyond the social norms, with the masquerade and the carnival.”

Art and the Grand Tour

Bound up with the idea of independence was the need to collect souvenirs, which the Grand Tourists could display in their homes.

“The ownership of property was tied to status, so creating a material legacy was really important for the Grand Tourists in order to solidify their social standing amongst their peers,” says Gazzard. “They were looking to spend money and buy mementos to prove they went on the trip.”

The works of artists such as those of the 18th century view painter Giovanni Antonio Canal (known as Canaletto ) were especially popular with Grand Tourists. Prized for their detail, Canaletto’s artworks captured the landmarks and scenes of everyday Venetian life, from festive scenes to bustling traffic on the Grand Canal .

In 1731, Lord John Russell, the future 4th Duke of Bedford, commissioned Canaletto to create 24 Venetian views following his visit to the city.

Lord John Russell is known to have paid at least £188 for the set – over five times the annual earnings of a skilled tradesperson at the time.

“Canaletto’s work was portable and collectible,” says Gazzard. “He adopted a smaller size for his canvases so they could be rolled up and shipped easily.”

These detailed works, now part of the world famous collection at Woburn Abbey, form the centrepiece of Canaletto’s Venice Revisited at the National Maritime Museum .

Who was Canaletto?

The legacy of the Grand Tour

The start of the French Revolution in 1789 marked the end of the Grand Tour. However, its legacy is still keenly felt.

The desire to explore and learn about different places and cultures through travel continues to endure. The legacy of the Grand Tour can also be seen in the artworks and objects that adorn the walls of stately homes and museums, and the many cultural influences that travellers brought back to Britain.

Canaletto's Venice Revisited

Main image: The Piazza San Marco looking towards the Basilica San Marco and the Campanile by Canaletto . From the Woburn Abbey Collection . Canaletto painting in body copy: Regatta on Grand Canal by Canaletto From the Woburn Abbey Collection

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

The grand tour.

Marble sarcophagus with the Triumph of Dionysos and the Seasons

Piazza San Marco

Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal)

Autre Vue Particulière de Paris depuis Nôtre Dame, Jusques au Pont de la Tournelle

Jacques Rigaud

Imaginary View of Venice, houses at left with figures on terraces, a domed church at center in the background, boats and boat-sheds below, and a seated man observing from a wall at right in the foreground, from 'Views' (Vedute altre prese da i luoghi altre ideate da Antonio Canal)

The Piazza del Popolo (Veduta della Piazza del Popolo), from "Vedute di Roma"

Giovanni Battista Piranesi

Vue de la Grande Façade du Vieux Louvre

View of St. Peter's and the Vatican from the Janiculum

Richard Wilson

Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768)

Anton Raphael Mengs

Modern Rome

Giovanni Paolo Panini

Ancient Rome

Portrait of a Young Man

Pompeo Batoni

Gardens of the Villa d'Este at Tivoli

Charles Joseph Natoire

Veduta dell'Anfiteatro Flavio detto il Colosseo, from: 'Vedute di Roma' (Views of Rome)

View of the Villa Lante on the Janiculum in Rome

John Robert Cozens

The Girandola at the Castel Sant'Angelo

Designed and hand colored by Louis Jean Desprez

Dining room from Lansdowne House

After a design by Robert Adam

The Burial of Punchinello

Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo

Portland vase

Josiah Wedgwood and Sons

Jean Sorabella Independent Scholar

October 2003

Beginning in the late sixteenth century, it became fashionable for young aristocrats to visit Paris, Venice, Florence, and above all Rome, as the culmination of their classical education. Thus was born the idea of the Grand Tour, a practice that introduced Englishmen, Germans, Scandinavians, and also Americans to the art and culture of France and Italy for the next 300 years. Travel was arduous and costly throughout the period, possible only for a privileged class—the same that produced gentleman scientists, authors, antiquaries, and patrons of the arts.

The Objectives of the Grand Tour The Grand Tourist was typically a young man with a thorough grounding in Greek and Latin literature as well as some leisure time, some means, and some interest in art. The German traveler Johann Joachim Winckelmann pioneered the field of art history with his comprehensive study of Greek and Roman sculpture ; he was portrayed by his friend Anton Raphael Mengs at the beginning of his long residence in Rome ( 48.141 ). Most Grand Tourists, however, stayed for briefer periods and set out with less scholarly intentions, accompanied by a teacher or guardian, and expected to return home with souvenirs of their travels as well as an understanding of art and architecture formed by exposure to great masterpieces.

London was a frequent starting point for Grand Tourists, and Paris a compulsory destination; many traveled to the Netherlands, some to Switzerland and Germany, and a very few adventurers to Spain, Greece, or Turkey. The essential place to visit, however, was Italy. The British traveler Charles Thompson spoke for many Grand Tourists when in 1744 he described himself as “being impatiently desirous of viewing a country so famous in history, which once gave laws to the world; which is at present the greatest school of music and painting, contains the noblest productions of statuary and architecture, and abounds with cabinets of rarities , and collections of all kinds of antiquities.” Within Italy, the great focus was Rome, whose ancient ruins and more recent achievements were shown to every Grand Tourist. Panini’s Ancient Rome ( 52.63.1 ) and Modern Rome ( 52.63.2 ) represent the sights most prized, including celebrated Greco-Roman statues and views of famous ruins, fountains, and churches. Since there were few museums anywhere in Europe before the close of the eighteenth century, Grand Tourists often saw paintings and sculptures by gaining admission to private collections, and many were eager to acquire examples of Greco-Roman and Italian art for their own collections. In England, where architecture was increasingly seen as an aristocratic pursuit, noblemen often applied what they learned from the villas of Palladio in the Veneto and the evocative ruins of Rome to their own country houses and gardens .

The Grand Tour and the Arts Many artists benefited from the patronage of Grand Tourists eager to procure mementos of their travels. Pompeo Batoni painted portraits of aristocrats in Rome surrounded by classical staffage ( 03.37.1 ), and many travelers bought Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s prints of Roman views, including ancient structures like the Colosseum ( 59.570.426 ) and more recent monuments like the Piazza del Popolo ( 37.45.3[49] ), the dazzling Baroque entryway to Rome. Some Grand Tourists invited artists from home to accompany them throughout their travels, making views specific to their own itineraries; the British artist Richard Wilson, for example, made drawings of Italian places while traveling with the earl of Dartmouth in the mid-eighteenth century ( 1972.118.294 ).

Classical taste and an interest in exotic customs shaped travelers’ itineraries as well as their reactions. Gothic buildings , not much esteemed before the late eighteenth century, were seldom cause for long excursions, while monuments of Greco-Roman antiquity, the Italian Renaissance, and the classical Baroque tradition received praise and admiration. Jacques Rigaud’s views of Paris were well suited to the interests of Grand Tourists, displaying, for example, the architectural grandeur of the Louvre, still a royal palace, and the bustle of life along the Seine ( 53.600.1191 ; 53.600.1175 ). Canaletto’s views of Venice ( 1973.634 ; 1988.162 ) were much prized, and other works appealed to Northern travelers’ interest in exceptional fêtes and customs: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo ‘s Burial of Punchinello ( 1975.1.473 ), for instance, is peopled with characters from the Venetian carnival, and a print by Francesco Piranesi and Louis Jean Desprez depicts the Girandola, a spectacular fireworks display held at the Castel Sant’Angelo ( 69.510 ).

The Grand Tour and Neoclassical Taste The Grand Tour gave concrete form to northern Europeans’ ideas about the Greco-Roman world and helped foster Neoclassical ideals . The most ambitious tourists visited excavations at such sites as Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Tivoli, and purchased antiquities to decorate their homes. The third duke of Beaufort brought from Rome the third-century work named the Badminton Sarcophagus ( 55.11.5 ) after the house where he proudly installed it in Gloucestershire. The dining rooms of Robert Adam’s interiors typically incorporated classical statuary; the nine lifesized figures set in niches in the Lansdowne dining room ( 32.12 ) were among the many antiquities acquired by the second earl of Shelburne, whose collecting activities accelerated after 1771, when he visited Italy and met Gavin Hamilton, a noted antiquary and one of the first dealers to take an interest in Attic ceramics, then known as “Etruscan vases.” Early entrepreneurs recognized opportunities created by the culture of the Grand Tour: when the second duchess of Portland obtained a Roman cameo glass vase in a much-publicized sale, Josiah Wedgwood profited from the manufacture of jasper reproductions ( 94.4.172 ).

Sorabella, Jean. “The Grand Tour.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/grtr/hd_grtr.htm (October 2003)

Further Reading

Black, Jeremy. The British and the Grand Tour . London: Croom Helm, 1985.

Black, Jeremy. Italy and the Grand Tour . New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

Black, Jeremy. France and the Grand Tour . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

Haskell, Francis, and Nicholas Penny. Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture, 1500–1900 . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981.

Wilton, Andrew, and Ilaria Bignamini, eds. The Grand Tour: The Lure of Italy in the Eighteenth Century . Exhibition catalogue. London: Tate Gallery Publishing, 1996.

Additional Essays by Jean Sorabella

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Pilgrimage in Medieval Europe .” (April 2011)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Portraiture in Renaissance and Baroque Europe .” (August 2007)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Venetian Color and Florentine Design .” (October 2002)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Art of the Roman Provinces, 1–500 A.D. .” (May 2010)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Nude in Baroque and Later Art .” (January 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Nude in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance .” (January 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Nude in Western Art and Its Beginnings in Antiquity .” (January 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Monasticism in Western Medieval Europe .” (originally published October 2001, last revised March 2013)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Interior Design in England, 1600–1800 .” (October 2003)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Vikings (780–1100) .” (October 2002)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Painting the Life of Christ in Medieval and Renaissance Italy .” (June 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Birth and Infancy of Christ in Italian Painting .” (June 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Crucifixion and Passion of Christ in Italian Painting .” (June 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Carolingian Art .” (December 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Ottonian Art .” (September 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Ballet .” (October 2004)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Baroque Rome .” (October 2003)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Opera .” (October 2004)

Related Essays

- American Neoclassical Sculptors Abroad

- Baroque Rome

- The Idea and Invention of the Villa

- Neoclassicism

- The Rediscovery of Classical Antiquity

- Antonio Canova (1757–1822)

- Architecture in Renaissance Italy

- Athenian Vase Painting: Black- and Red-Figure Techniques

- The Augustan Villa at Boscotrecase

- Collecting for the Kunstkammer

- Commedia dell’arte

- The Eighteenth-Century Pastel Portrait

- Exoticism in the Decorative Arts

- Gardens in the French Renaissance

- Gardens of Western Europe, 1600–1800

- George Inness (1825–1894)

- Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778)

- Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770)

- Images of Antiquity in Limoges Enamels in the French Renaissance

- James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903)

- Joachim Tielke (1641–1719)

- John Frederick Kensett (1816–1872)

- Photographers in Egypt

- The Printed Image in the West: Etching

- Roman Copies of Greek Statues

- Theater and Amphitheater in the Roman World

- Anatolia and the Caucasus, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Balkan Peninsula, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Central Europe (including Germany), 1600–1800 A.D.

- Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Florence and Central Italy, 1600–1800 A.D.

- France, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Iberian Peninsula, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Low Countries, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Rome and Southern Italy, 1600–1800 A.D.

- The United States, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Venice and Northern Italy, 1600–1800 A.D.

- 16th Century A.D.

- 17th Century A.D.

- 18th Century A.D.

- 19th Century A.D.

- Ancient Roman Art

- Baroque Art

- Central Europe

- Central Italy

- Classical Ruins

- Great Britain and Ireland

- Greek and Roman Mythology

- The Netherlands

- Palladianism

- Period Room

- Southern Italy

- Switzerland

Artist or Maker

- Adam, Robert

- Batoni, Pompeo

- Cozens, John Robert

- Desprez, Louis Jean

- Mengs, Anton Raphael

- Natoire, Charles Joseph

- Panini, Giovanni Paolo

- Permoser, Balthasar

- Piranesi, Francesco

- Piranesi, Giovanni Battista

- Rigaud, Jacques

- Tiepolo, Giovanni Battista

- Tiepolo, Giovanni Domenico

- Wedgwood, Josiah

- Wilson, Richard

Online Features

- Connections: “Flux” by Annie Labatt

- Connections: “Genoa” by Xavier Salomon

Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

The History Hit Miscellany of Facts, Figures and Fascinating Finds

What Was the Grand Tour of Europe?

Lucy Davidson

26 jan 2022, @lucejuiceluce.

In the 18th century, a ‘Grand Tour’ became a rite of passage for wealthy young men. Essentially an elaborate form of finishing school, the tradition saw aristocrats travel across Europe to take in Greek and Roman history, language and literature, art, architecture and antiquity, while a paid ‘cicerone’ acted as both a chaperone and teacher.

Grand Tours were particularly popular amongst the British from 1764-1796, owing to the swathes of travellers and painters who flocked to Europe, the large number of export licenses granted to the British from Rome and a general period of peace and prosperity in Europe.

However, this wasn’t forever: Grand Tours waned in popularity from the 1870s with the advent of accessible rail and steamship travel and the popularity of Thomas Cook’s affordable ‘Cook’s Tour’, which made mass tourism possible and traditional Grand Tours less fashionable.

Here’s the history of the Grand Tour of Europe.

Who went on the Grand Tour?

In his 1670 guidebook The Voyage of Italy , Catholic priest and travel writer Richard Lassells coined the term ‘Grand Tour’ to describe young lords travelling abroad to learn about art, culture and history. The primary demographic of Grand Tour travellers changed little over the years, though primarily upper-class men of sufficient means and rank embarked upon the journey when they had ‘come of age’ at around 21.

‘Goethe in the Roman Campagna’ by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein. Rome 1787.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Grand Tours also became fashionable for women who might be accompanied by a spinster aunt as a chaperone. Novels such as E. M. Forster’s A Room With a View reflected the role of the Grand Tour as an important part of a woman’s education and entrance into elite society.

Increasing wealth, stability and political importance led to a more broad church of characters undertaking the journey. Prolonged trips were also taken by artists, designers, collectors, art trade agents and large numbers of the educated public.

What was the route?

The Grand Tour could last anything from several months to many years, depending on an individual’s interests and finances, and tended to shift across generations. The average British tourist would start in Dover before crossing the English Channel to Ostend in Belgium or Le Havre and Calais in France. From there the traveller (and if wealthy enough, group of servants) would hire a French-speaking guide before renting or acquiring a coach that could be both sold on or disassembled. Alternatively, they would take the riverboat as far as the Alps or up the Seine to Paris .

Map of grand tour taken by William Thomas Beckford in 1780.

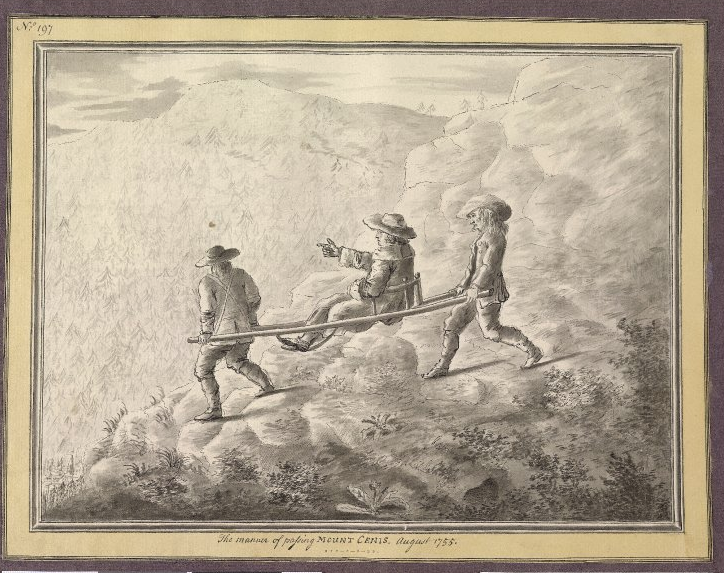

From Paris, travellers would normally cross the Alps – the particularly wealthy would be carried in a chair – with the aim of reaching festivals such as the Carnival in Venice or Holy Week in Rome. From there, Lucca, Florence, Siena and Rome or Naples were popular, as were Venice, Verona, Mantua, Bologna, Modena, Parma, Milan, Turin and Mont Cenis.

What did people do on the Grand Tour?

A Grand Tour was both an educational trip and an indulgent holiday. The primary attraction of the tour lay in its exposure of the cultural legacy of classical antiquity and the Renaissance, such as the excavations at Herculaneum and Pompeii, as well as the chance to enter fashionable and aristocratic European society.

Johann Zoffany: The Gore Family with George, third Earl Cowper, c. 1775.

In addition, many accounts wrote of the sexual freedom that came with being on the continent and away from society at home. Travel abroad also provided the only opportunity to view certain works of art and potentially the only chance to hear certain music.

The antiques market also thrived as lots of Britons, in particular, took priceless antiquities from abroad back with them, or commissioned copies to be made. One of the most famous of these collectors was the 2nd Earl of Petworth, who gathered or commissioned some 200 paintings and 70 statues and busts – mainly copies of Greek originals or Greco-Roman pieces – between 1750 and 1760.

It was also fashionable to have your portrait painted towards the end of the trip. Pompeo Batoni painted over 175 portraits of travellers in Rome during the 18th century.

Others would also undertake formal study in universities, or write detailed diaries or accounts of their experiences. One of the most famous of these accounts is that of US author and humourist Mark Twain, whose satirical account of his Grand Tour in Innocents Abroad became both his best selling work in his own lifetime and one of the best-selling travel books of the age.

Why did the popularity of the Grand Tour decline?

A Thomas Cook flyer from 1922 advertising cruises down the Nile. This mode of tourism has been immortalised in works such as Death on the Nile by Agatha Christie.

The popularity of the Grand Tour declined for a number of reasons. The Napoleonic Wars from 1803-1815 marked the end of the heyday of the Grand Tour, since the conflict made travel difficult at best and dangerous at worst.

The Grand Tour finally came to an end with the advent of accessible rail and steamship travel as a result of Thomas Cook’s ‘Cook’s Tour’, a byword of early mass tourism, which started in the 1870s. Cook first made mass tourism popular in Italy, with his train tickets allowing travel over a number of days and destinations. He also introduced travel-specific currencies and coupons which could be exchanged at hotels, banks and ticket agencies which made travelling easier and also stabilised the new Italian currency, the lira.

As a result of the sudden potential for mass tourism, the Grand Tour’s heyday as a rare experience reserved for the wealthy came to a close.

Can you go on a Grand Tour today?

Echoes of the Grand Tour exist today in a variety of forms. For a budget, multi-destination travel experience, interrailing is your best bet; much like Thomas Cook’s early train tickets, travel is permitted along many routes and tickets are valid for a certain number of days or stops.

For a more upmarket experience, cruising is a popular choice, transporting tourists to a number of different destinations where you can disembark to enjoy the local culture and cuisine.

Though the days of wealthy nobles enjoying exclusive travel around continental Europe and dancing with European royalty might be over, the cultural and artistic imprint of a bygone Grand Tour era is very much alive.

To plan your own Grand Tour of Europe, take a look at History Hit’s guides to the most unmissable heritage sites in Paris , Austria and, of course, Italy .

You May Also Like

Mac and Cheese in 1736? The Stories of Kensington Palace’s Servants

The Peasants’ Revolt: Rise of the Rebels

10 Myths About Winston Churchill

Medusa: What Was a Gorgon?

10 Facts About the Battle of Shrewsbury

5 of Our Top Podcasts About the Norman Conquest of 1066

How Did 3 People Seemingly Escape From Alcatraz?

5 of Our Top Documentaries About the Norman Conquest of 1066

1848: The Year of Revolutions

What Prompted the Boston Tea Party?

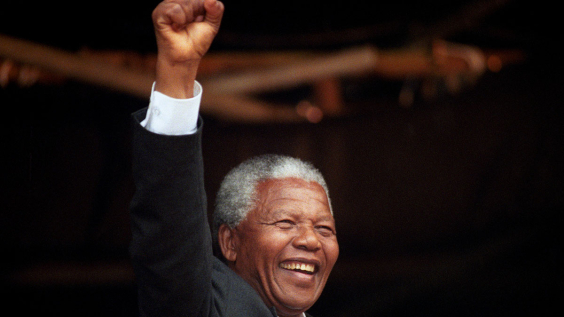

15 Quotes by Nelson Mandela

The History of Advent

The Grand Tour: a rite of passage for Europe’s elite

Wealthy Europeans of the 17th and 18th centuries often embarked on a Grand Tour, just like Colin Bridgerton in the latest series of Netflix’s sumptuous Regency-era drama Bridgerton . But what was it, and why was it such a cultural phenomenon?

- Share on facebook

- Share on twitter

- Share on whatsapp

- Email to a friend

During the late 16th century, a cultural phenomenon emerged among Europe’s elite: the Grand Tour.

Essentially a long excursion around the continent’s ancient locations, the Grand Tour would endure for over three centuries and become a rite of passage for (typically) young male aristocrats, capping off an education steeped in reverence for the Classical world.

Its zenith was during the 18th century, whereupon it gradually waned throughout the 19th century.

How did the Grand Tour get its name?

Richard Lassels, a Roman Catholic priest, coined the term ‘Grand Tour’ in his 1670 travelogue, The Voyage of Ital y – although the tradition began decades earlier.

Who went on the Grand Tour?

The archetypal Grand Tourist was a young man of means and leisure, well-versed in Greek and Latin literature and possessing a keen interest in art.

Accompanied by a tutor, British Grand Tourists often travelled by horse-drawn coach for days, before arriving in Dover and waiting for favourable weather conditions in which to cross the English Channel.

Inigo Jones, the celebrated architect, embarked on one of the earliest recorded tours in 1613–14. His experiences in Italy influenced his aesthetic, evident in projects like the Queen’s House in Greenwich, and revolutionised the trajectory of British architecture.

Cities of the Grand Tour: what was the route?

Alighting at Le Havre in France, Grand Tourists usually converged with their peers from other countries in Paris .

The onward journey south would either entail traversing the alpine Mount Cenis Pass or going via the sea from Marseilles.

Italy, with its rich artistic and architectural heritage, was the ultimate destination. Cities like Venice, Florence , Rome and Naples captivated visitors with their famed histories, artistic treasures and ancient ruins.

Itineraries could vary, with destinations evolving over time to include places like Herculaneum , Pompeii , Sicily and Athens .

Take your own Grand Tour with History’s greatest cities

Listen to all episodes now.

What did Grand Tourists hope to gain from the experience?

As the odyssey unfolded, the impressionable travellers – in many cases, the future governing class of their respective homelands – were also expected to acquire a knowledge of Europe’s political, philosophical and economic trends.

But the Grand Tour was not only a scholarly undertaking: it was also an assertion of independence and status. Stopovers like Venice, with its gambling houses and revelry, dazzled pleasure seekers.

Guides, known as ‘cicerones’, accompanied many Grand Tourists, offering both cultural insights and chaperoning, while popular artworks by the likes of Canaletto and Piranesi were snapped up as desirable souvenirs of the Continent’s resonant vistas and landmarks.

For many young Europeans, the Grand Tour was more than an excursion; it was a mission undertaken in pursuit of national service, so as to enrich their country’s culture and standing.

Surviving letters and diaries provide invaluable glimpses into the experiences of Grand Tourists, revealing their impression of European culture – something that was often reflected in the lasting impact it had on the design of their estates back home.

When did the Grand Tour decline?

By the late 18th century, the tradition of the Grand Tour was interrupted by the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars , only to resume following Napoleon ’s downfall in 1815.

The advent of railways in the mid-19th century began to democratise travel as a leisure pursuit, making it more accessible and marketable to the burgeoning middle class, bringing the era of the Grand Tour to an end.

Danny Bird is the Staff Writer at BBC History Magazine. Danny Bird is the Staff Writer at BBC History Magazine and previously held the same role on BBC History Revealed. He joined the brand in 2022. Fascinated with the past since childhood, Danny completed his History BA at the University of Sheffield, developing a special interest in the Spanish Civil War and the Paris Commune. He subsequently gained his History MA from University College London, studying at its School of Slavonic and East European Studies (SSEES)

Receive a hardback and signed copy of a book of your choice when when you subscribe for £24.99 every 6 issues.

+ FREE HistoryExtra membership - worth £34.99!

Sign up for the weekly HistoryExtra newsletter

Sign up to receive our newsletter!

By entering your details, you are agreeing to our terms and conditions and privacy policy . You can unsubscribe at any time.

Subscriber today and get your Summer Read

+ FREE HistoryExtra membership & 15% Chalke History Tickets

USA Subscription offer!

Save 76% on the shop price when you subscribe today - Get 13 issues for just $45 + FREE access to HistoryExtra.com

HistoryExtra podcast

Listen to the latest episodes now

18th Century Grand Tour of Europe

The Travels of European Twenty-Somethings

Print Collector/Getty Images

- Key Figures & Milestones

- Physical Geography

- Political Geography

- Country Information

- Urban Geography

- M.A., Geography, California State University - Northridge

- B.A., Geography, University of California - Davis

The French Revolution marked the end of a spectacular period of travel and enlightenment for European youth, particularly from England. Young English elites of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries often spent two to four years touring around Europe in an effort to broaden their horizons and learn about language , architecture , geography, and culture in an experience known as the Grand Tour.

The Grand Tour, which didn't come to an end until the close of the eighteenth century, began in the sixteenth century and gained popularity during the seventeenth century. Read to find out what started this event and what the typical Tour entailed.

Origins of the Grand Tour

Privileged young graduates of sixteenth-century Europe pioneered a trend wherein they traveled across the continent in search of art and cultural experiences upon their graduation. This practice, which grew to be wildly popular, became known as the Grand Tour, a term introduced by Richard Lassels in his 1670 book Voyage to Italy . Specialty guidebooks, tour guides, and other aspects of the tourist industry were developed during this time to meet the needs of wealthy 20-something male and female travelers and their tutors as they explored the European continent.

These young, classically-educated Tourists were affluent enough to fund multiple years abroad for themselves and they took full advantage of this. They carried letters of reference and introduction with them as they departed from southern England in order to communicate with and learn from people they met in other countries. Some Tourists sought to continue their education and broaden their horizons while abroad, some were just after fun and leisurely travels, but most desired a combination of both.

Navigating Europe

A typical journey through Europe was long and winding with many stops along the way. London was commonly used as a starting point and the Tour was usually kicked off with a difficult trip across the English Channel.

Crossing the English Channel

The most common route across the English Channel, La Manche, was made from Dover to Calais, France—this is now the path of the Channel Tunnel. A trip from Dover across the Channel to Calais and finally into Paris customarily took three days. After all, crossing the wide channel was and is not easy. Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Tourists risked seasickness, illness, and even shipwreck on this first leg of travel.

Compulsory Stops

Grand Tourists were primarily interested in visiting cities that were considered major centers of culture at the time, so Paris, Rome, and Venice were not to be missed. Florence and Naples were also popular destinations but were regarded as more optional than the aforementioned cities.

The average Grand Tourist traveled from city to city, usually spending weeks in smaller cities and up to several months in the three major ones. Paris, France was the most popular stop of the Grand Tour for its cultural, architectural, and political influence. It was also popular because most young British elite already spoke French, a prominent language in classical literature and other studies, and travel through and to this city was relatively easy. For many English citizens, Paris was the most impressive place visited.

Getting to Italy

From Paris, many Tourists proceeded across the Alps or took a boat on the Mediterranean Sea to get to Italy, another essential stopping point. For those who made their way across the Alps, Turin was the first Italian city they'd come to and some remained here while others simply passed through on their way to Rome or Venice.

Rome was initially the southernmost point of travel. However, when excavations of Herculaneum (1738) and Pompeii (1748) began, these two sites were added as major destinations on the Grand Tour.

Features of the Grand Tour

The vast majority of Tourists took part in similar activities during their exploration with art at the center of it all. Once a Tourist arrived at a destination, they would seek housing and settle in for anywhere from weeks to months, even years. Though certainly not an overly trying experience for most, the Grand Tour presented a unique set of challenges for travelers to overcome.

While the original purpose of the Grand Tour was educational, a great deal of time was spent on much more frivolous pursuits. Among these were drinking, gambling, and intimate encounters—some Tourists regarded their travels as an opportunity to indulge in promiscuity with little consequence. Journals and sketches that were supposed to be completed during the Tour were left blank more often than not.

Visiting French and Italian royalty as well as British diplomats was a common recreation during the Tour. The young men and women that participated wanted to return home with stories to tell and meeting famous or otherwise influential people made for great stories.

The study and collection of art became almost a nonoptional engagement for Grand Tourists. Many returned home with bounties of paintings, antiques, and handmade items from various countries. Those that could afford to purchase lavish souvenirs did so in the extreme.

Arriving in Paris, one of the first destinations for most, a Tourist would usually rent an apartment for several weeks or months. Day trips from Paris to the French countryside or to Versailles (the home of the French monarchy) were common for less wealthy travelers that couldn't pay for longer outings.

The homes of envoys were often utilized as hotels and food pantries. This annoyed envoys but there wasn't much they could do about such inconveniences caused by their citizens. Nice apartments tended to be accessible only in major cities, with harsh and dirty inns the only options in smaller ones.

Trials and Challenges

A Tourist would not carry much money on their person during their expeditions due to the risk of highway robberies. Instead, letters of credit from reputable London banks were presented at major cities of the Grand Tour in order to make purchases. In this way, tourists spent a great deal of money abroad.

Because these expenditures were made outside of England and therefore did not bolster England's economy, some English politicians were very much against the institution of the Grand Tour and did not approve of this rite of passage. This played minimally into the average person's decision to travel.

Returning to England

Upon returning to England, tourists were meant to be ready to assume the responsibilities of an aristocrat. The Grand Tour was ultimately worthwhile as it has been credited with spurring dramatic developments in British architecture and culture, but many viewed it as a waste of time during this period because many Tourists did not come home more mature than when they had left.

The French Revolution in 1789 halted the Grand Tour—in the early nineteenth century, railroads forever changed the face of tourism and foreign travel.

- Burk, Kathleen. "The Grand Tour of Europe". Gresham College, 6 Apr. 2005.

- Knowles, Rachel. “The Grand Tour.” Regency History , 30 Apr. 2013.

- Sorabella, Jean. “The Grand Tour.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History , The Met Museum, Oct. 2003.

- A Beginner's Guide to the Enlightenment

- The History of Venice

- Architecture in France: A Guide For Travelers

- A Brief History of Rome

- The Top 10 Major Cities in France

- The Best Books on Early Modern European History (1500 to 1700)

- What Is a Monarchy?

- Renaissance Architecture and Its Influence

- A Beginner's Guide to the Renaissance

- Female European Historical Figures: 1500 - 1945

- 8 Major Events in European History

- The 12 Best Books on the French Revolution

- William Turner, English Romantic Landscape Painter

- Architecture in Italy for the Lifelong Learner

- 18 Key Thinkers of the Enlightenment

- Biography of Harriet Quimby

The lavish Grand Tours of history — and how they shaped the way we travel today

It was a rite of passage for young, upper-class Englishmen with virtually unlimited money to burn — a hedonistic "Grand Tour" far from home, unfolding over two or three or even four years.

Designed to teach them about art, history and culture, it was a kind of finishing school that would ready them for life in the powerful ruling elite.

Unsurprisingly, sex, gambling, drinking, and lavish parties also found their way into the mix.

For many historians, these travellers of the 17th and 18th centuries represent the first modern tourists.

They fuelled a passion for adventure and paved the way for the type of travel we know (and miss) today.

The ultimate destinations

The Grand Tour began in about 1660 and reached its zenith between 1748 and 1789.

It was typically undertaken by men aged between 18 and 25 — the sons of the aristocracy.

First, they braved the English Channel to reach Belgium or France. There, many purchased a carriage for the onward journey.

They were accompanied by a guide, known as a "bear-leader", who tutored them in art, music, literature and history.

If they were wealthy enough, their entourage included a troop of servants.

While there was no fixed route, most tours included the great cities of Europe — Paris, Geneva, Berlin — and a lengthy sojourn in Italy.

"A man who has not been in Italy is always conscious of an inferiority, from his not having seen what it is expected a man should see," English author Samuel Johnson remarked in 1776.

Rome was considered the ultimate destination, but Venice, Florence, Milan and Naples were also high on the list.

A drive for education and enlightenment was at the heart of the tour.

The Grand Tourists looked at art, admired monuments, visited historical sites, and studied classical architecture. They mingled with the elite social classes.

Behaving badly

They were students with practically unlimited budgets, and often very little supervision.

European history expert Eric Zuelow says this meant they were "apt to behave in a rather different way with rather different interests than the Grand Tour was designed to instil in them".

"So what they tended to do was to go and drink a lot, to gamble, to frequent [sex workers]," he tells ABC RN's Rear Vision .

"They tended not to learn much in the way of languages, not to learn much in the way of culture, but to have a lot of fun.

"And that created, I would argue, really one of the first instances of the notion of tourists as being lesser creatures and travellers being something much better.

"The first tourists, the Grand Tourists, did not behave all that well. And tourists have held that stigma ever since."

It wasn ' t all smooth sailing

In the days of the Grand Tour, travel wasn't for the faint-hearted.

There are many reports of the young men becoming ill from travel sickness, rough seas and foreign foods.

Disease was another threat — during his Grand Tour, writer John Evelyn nearly died of smallpox in Geneva.

Thieves were highly active, so many Grand Tourists didn't carry cash, instead taking the equivalent of travellers' cheques.

Roads were rough and full of potholes, and the carriages could only journey about 20 kilometres a day. Some parts of the trip were undertaken by foot.

"So they could be weeks just getting from one place to another," says historian Susan Barton.

Crossing the Alps was a particular challenge.

Some Grand Tourists hired a sedan chair to be carried, literally, over the mountain passes.

The "chairmen of Mont Cenis" became known throughout the Alps for their strength and dexterity.

The rise of 'self-illusory hedonistic consumption'

These early travellers carried guidebooks, which advised them of what to see, hear and do.

They were told to show their wealth at every turn, to garner respect.

As time went by, those making the Grand Tour also became shoppers. They wanted to buy things they could later show off.

"What was happening at this time was a development of what one scholar called 'self-illusory hedonistic consumption', which is a really fancy term for spending money because buying things will make you better," Professor Zuelow says.

"The Grand Tour, with its original educational roots, merged with that self-illusory, hedonistic idea, creating a consumable."

The young tourists would return to England with bulging luggage — marble statues from Rome, colourful glassware from Venice, pumice stone from Naples.

They brought back paintings depicting the Colosseum in Rome, the canals in Venice, the Parthenon in Athens.

They'd also commission portraits of themselves, and a mini industry sprung up around this.

It wasn't just to remind themselves of all they had seen and done. It was so other people would also know.

The souvenirs were displayed with great pride in the family's estates and manor houses.

"And later some of those things ended up in museums," Dr Barton says.

"So in a way they were creating the future 20th century tourism where people were visiting country houses as part of their leisure."

Not all Britons — and not all men

Although Britons far outnumbered all others, Professor Zuelow notes that they weren't the only Grand Tourists.

Peter the Great, the Russian Tsar, famously made the trip, as did German philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and King Gustav III of Sweden.

And it also wasn't just men.

Professor Zuelow says English women such as author Mary Wollstonecraft and socialite Lady Mary Wortley Montagu spent extensive time in Europe, enjoying new freedoms and the chance for an education not available to them back home.

Travel for leisure and the Grand Tour's legacy

By 1815, the Grand Tour was disappearing.

Professor Zuelow says part of the reason for this is obvious: the French Revolution, followed closely by the Napoleonic Wars, swept across Europe starting in 1789 and extended until 1815.

"When the fighting stopped, many visitors returned — even if only to see the damages of war — but this was no longer the old Grand Tour," he writes in his book, A History of Modern Travel.

After 1815, travel to Europe slowly opened up for much wider social groups.

"So rather than just the aristocracy, we've got middle class people starting to travel, but it was still quite a lengthy process," Dr Barton says.

The legacy of the Grand Tour lives on to this day.

It still influences the destinations we visit, and has shaped the ideas of culture and sophistication that surround the act of travel.

It shaped the notion that there's something to be gained from venturing overseas, that there's a lot on offer if you can leave home to find it.

"Prior to the Grand Tour, there wasn't a lot of travel for leisure," Professor Zuelow says.

"Medieval pilgrims have been put forward as possible tourists but they were travelling for religious purposes. And although they had a lot of fun along the way, it really was about getting into Heaven."

Many of the Grand Tourists wrote about their adventures, fuelling a new level of wanderlust in society.

The trips were the stuff of fantasy, and others wanted to follow.

It was a first step in the direction of mass tourism, and the kind of travel we know today.

"I define it really as travelling for the purpose of travelling, travelling for fun, travelling for enjoyment, feeling that travel is going to make you healthier and happier and a better person," Professor Zuelow says.

To hear more about the history of travel, the impact of technology on tourism, and the future may hold, listen to ABC Radio National's Rear Vision podcast .

RN in your inbox

Get more stories that go beyond the news cycle with our weekly newsletter.

- X (formerly Twitter)

Related Stories

Pay with a credit card, and other tips to covid-proof your next holiday.

It's so bad Qantas is selling its pyjamas — but flying's new reality is not as grim

Guide Alice and the 'sleeping buffalo' that stole her heart

- Community and Society

- European Union

- Human Interest

- Lifestyle and Leisure

- Travel and Tourism (Lifestyle and Leisure)

- United Kingdom

- United States

British Travelers in Eighteenth-Century Italy: The Grand Tour and the Profession of Architecture

As published in the American Historical Review by Giovanna Ceserani, Giorgio Caviglia, Nicole Coleman, Thea De Armond, Sarah Murray, and Molly Taylor-Poleskey:

"Drawing on a dynamic digital database of eighteenth-century British travelers in Italy, in this article we offer a case study focused on British architects to demonstrate the potential of digital resources for historical research. Based on the entries in John Ingammels’s Dictionary of British and Irish Travellers in Italy, 1701–1800 (1997)—which covers the itineraries and lives of more than five thousand travelers—our project adds a new richness and granularity to the understanding of the Grand Tour. We see what these tours were like and what they did for British architects in Italy and beyond. We show the patterns of places visited, of funding, of social and professional gains and interactions, and we thus catch sight of a history of architecture that goes beyond the influence of Italian architectural models on British thought and design. This approach to the Grand Tour reveals the transformation of “architecture” from a gentlemanly passion and artisanal craft into a modern profession and discipline. By indicating some of the ways in which the Grand Tour served this transformation, this case study also suggests the broader promise of our digital approach for scholars of various interests."

EDITORIAL FEATURE

The Art That Made Grand Tourists Flock to Italy

There were many reasons that travelers decided to embark on the Grand Tour of Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries, but the primary one was to see the artistic gems of Ancient and Renaissance Italy. As many still do today in fact.

As well as visiting history’s greatest treasures, Grand Tourists were also in the business of commissioning new art during their travels. Oftentimes, wealthy Grand Tourists would bring professional sketch artists along with them, whose whole purpose was to create souvenirs to take home. If this was not possible, Grand Tourists would have artworks made for them in Italy. A Venetian sketch artist who was widely popular during the Grand Tour was Giovanni Battista Piranesi , whose prints are still passed down through noble families today. And some more creative tourists would sketch Italian scenes themselves. After all, learning the arts first hand was, in essence, central to a formative intellectual voyage like this one.

From Rome to Venice, embark on a virtual tour of Italy’s art hotspots, to discover the art the Grand Tourists pursued, as well as the art they produced.

Rome: The Capital of the World A Grand Tourist’s base itinerary for Italy included must-see cities like Venice, Florence, Naples and sometimes Sicily. And then, of course, there’s Rome . Each Italian city offered immense historic importance in Greco-Roman antiquity, Renaissance art and culture or Baroque architecture. But Rome had it all.

Rome was considered the ultimate stop during the Grand Tour, as it was both a portal back in time thousands of years, as well as a modern-day marvel of Baroque art and architecture. It was lauded as the land of Cicero, the birthplace of Julius Caesar, and home to some of Michelangelo’s most prized works.

Having only heard stories of masterpieces like the Sistine Chapel, tourists understood that the only way to truly experience Italian art and culture was to see this city in person.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Baroque masterpieces left their mark across Rome, making extraordinary art commonplace in areas such as Piazza Navona and the Spanish Steps. Tourists were drawn to spots like the Arch of Titus, the Colosseum and Porta del Popolo.

“Shall I ever forget the sensations I experienced upon slowly descending the hills, and crossing the bridge over the Tiber; when I entered an avenue between terraces and ornamented gates of villas, which leads to the Porto del Popolo…” – William Beckford, letter from the Grand Tour, 1780

Venice: The Floating City of Wealth and Art Venice is often seen as one of the most intriguing and magical cities in the world, and it was no different for the Grand Tourists. It was a must on any Grand Tour itinerary, largely thanks to the wealth the city had built itself from merchant trading and a strong navy. These were admirable qualities to an 18th-century British traveler.

Its reputation may be what brought tourists to Venice, but Venetian Renaissance art and culture is what kept them coming back.

Tourists visited Venice to see paintings by the great Titian , Giovanni Bellini , Jacopo Bassano and, of course, they wanted a Giovanni Battista Piranesi sketch to take back home with them.

One well-known cityscape artist was Canaletto . His acute attention to detail set him above the rest, capturing a lifelike scene that made tourists feel like they were almost taking a real slice of the city home with them.

Pompeii & Naples: Ancient Ruins, Sun & Light There were some Grand Tourists who championed lesser visited cities, oftentimes taking a direct journey to Naples – the land of sun, culture, opera buffa and a few of Caravaggio’s greats. Naples became more of a popular stop in the latter part of the Grand Tour, becoming something of a winter retreat for British tourists, with travelers like J.W. Goethe praising its glories.

“Naples is a Paradise: everyone lives in a state of intoxicated self-forgetfulness, myself included. I seem to be a completely different person whom I hardly recognize. Yesterday I thought to myself: Either you were mad before, or you are mad now.” – Goethe

Places like Pompeii and Herculaneum only added to the appeal of traveling further south in Italy, in search of the ruins that tied the present day to its historic roots. When Italian authorities began excavations of Herculaneum in 1738, and then later at Pompeii in 1748, tourists had even more reason to delve into the mysteries of an ancient past... and enjoy a bit of the coastal sun along the way.

Florence: British Nobility Meets the High Renaissance Known as the birthplace of the Renaissance , early Grand Tourists rarely skipped a stop to Florence , which, simply put, was a haven for art – no doubt thanks to its ornate grandeur in architecture, with examples including the Florence Cathedral and, of course, Filippo Brunelleschi’s Dome.

But there was one attraction which almost perfectly coincided with the new arrival of tourism to Italy – Cosimo I de’ Medici's idea to gain magisterial control of a series of Florentine “offices”, better known in Italian as the “uffizi”. These administrative offices were soon to become both administrative and tribunal, with a gallery on the second floor so that newly acquired art could be properly enjoyed.

The Uffizi Gallery as we know it was not open to the public until 1765, but some fortunate Grand Tourists (who for the most part were nobility or of high social status themselves) were privy to a viewing of works by Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo .

Upon seeing the Uffizi collection , Thomas Beckford, a noted art collector, said…

“…I fell into a delightful delirium which none but souls like us experience, and unable to check my rapture flew madly from bust to bust and cabinet to cabinet like a butterfly bewildered in a universe of flowers…’’

The Uffizi Galleries still remain one of the highlights of Florence.

Learn more about The Grand Tour:

- How Tourism Hasn’t Changed Since The Grand Tour - 9 Books and Films Inspired by the Grand Tour - The Grand Tour of Italy

The Grand Tour Of The 18th Century

In the eighteenth century, the Grand Tour was an obligatory part of a young nobleman’s artistic, intellectual and sentimental education.

The ‘Grand Tour’, that extended journey to Italy undertaken mainly by British but also French and German aristocrats in the eighteenth century, is not only the stuff of legend, but meant as many different things as there were tourists; each came back with a particular and personal view of the experience.

The Grand Tour evolved during the seventeenth century to become a formative experience for the leaders of British society. Princes, nobles, aristocrats, landed gentry, and politicians—with courtiers, retinues, scholars, tutors, advisors and servants—all made the journey across France. Crossing the Alps at Mont Cenis (usually carried in a chair), they descended into Italy at Turin, or, taking a felucca from Marseilles, they landed at Genoa.

Italy was seen as the cradle of Western civilisation, the source and home of all that was reckoned to be significant historically, aesthetically, politically, religiously and, above all, for collecting: antique sculpture, Old Master paintings, furniture, textiles, objets de vertu, jewellery, contemporary sculpture and painting.

In the latter category, most highly prized were portraits of the tourists themselves by masters such as Pompeo Batoni and ‘vedute’, views of the sites visited as presented in Canaletto’s paintings or Piranesi’s prints. Moreover, Italy was the textbook for students of architecture, with ancient and modern buildings not only to be studied but imitated back home. The British stately home is almost by definition the result of the Grand Tour in both its architecture and its contents.

Earlier this year, the ‘Italy Observed’ exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum in New York showcased a fine selection of Italian vedute, from paintings of Venetian life by Luca Carlevaris to a Neapolitan album of gouache drawings documenting the eruption of Vesuvius in 1794 to sketches and watercolours of Italian antiquities, capturing the artist’s romantic attraction to Italy and its irresistible Roman heritage.

The places to visit included most of the sites still popular with less grand tourists today: Florence, with untold riches held by the Grand-Ducal Medicis in their several city palaces, as well as works of art in the churches and monasteries; Venice, which combined artistic and mercantile wealth; Genoa, which had artistic links with Britain due to the visits of Rubens and Van Dyck whose works adorned that city; and Naples, the capital of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, an outpost of the Habsburg empire with a glamorous court and the place where in the later part of the eighteenth century Sir William Hamilton and his wife, Emma—later to achieve fame as Nelson’s lover—held cultural sway.

Later in the century the archaeological excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum put these on the tourist trail, as sites for the study of the ancient world, sources for yet more riches to be brought home, and templates for decoration and decorative art works in the Neo-classical style that emerged partly as a result of these finds. At the same time, Southern Italy and Sicily were added to the Tour as interest grew in classical Greek architecture, the temples at Paestum and Segesta being among the finest examples.

Above all others, the destination of the Grand Tour was Rome—the crossroads of the ancient and the Christian worlds—and the place that epitomised Western civilisation. The site of the vestiges of the Roman Republic and Empire, those sources of European law and administration, and of the noble examples of pagan virtue and rectitude that inspired the classical ideals of the Augustan gentleman, Rome was also the heart of European Christianity: for Catholics the very heart of the religion; for Protestants, although historically important if doctrinally suspect or downright repugnant, a power to be known and reckoned with.

However, the Grand Tourists were not pilgrims, but came with other motives—often mixed, but principally to drink from the source of civilisation, to undertake a Bildungsreise, the journey of a life time (often lasting several years), an experience that would form an aristocrat’s life-long attitudes, tastes, intellectual habits and manners. It was also a major shopping expedition intended to provide the nobility with objects to furnish their newly built Neo-classical houses.

Grand Tourists can be seen in works of art such as the portraits of Lord Mountstuart and John Talbot painted respectively by Jean-Étienne Liotard in 1763 and Pompeo Batoni, ten years later. Talbot is shown as the consummate Grand Tourist: elegant, poised, nonchalant, surrounded by the signs of his Roman sojourn—a broken capital at his feet, a Grecian urn at his elbow and the Ludovisi Ares in the background.

Tourists who had not done their homework before setting off were ably assisted by their tutors, the ubiquitous and often ill-used ‘bear leaders’, who were also meant to oversee their charges’ moral integrity, a fruitless task more often honoured in the breach.

In fact, the Grand Tourists’ less high-minded behaviour and interests were frequently remarked on—pointedly, in one instance by Alexander Pope who satirised the twin aspects of the Grand Tourist’s agenda: ‘… he sauntered Europe round, / And gather’d ev’ry Vice on Christian ground; / Saw ev’ry Court, heard ev’ry King declare / His royal Sense of Op’ra’s or the Fair; / The Stews and Palace equally explor’d / Intrigu’d with glory, and with spirit whor’d.’

But the Grand Tourist whose budget did not stretch to having a personal tutor was responsible for the invention of what has become an indispensable item of tourism: the guidebook, with foldout maps and panoramic views marked with the not-to-be-missed monuments and sites.

The beautiful red chalk drawing of an antique monument in a landscape by Marie-Joseph Peyre from about 1753-85 is an example that serves as reminder that many Grand Tourists were taught, on the spot, to draw, sketch and paint. The Grand Tourists’ collecting activities promoted the revival of ancient art forms, creating a taste for architecture and sculpture in a Neo-classical or Greek style, and in the manufacture of objects such as Wedgwood cameo wares.

The publication in 1755 of Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s Reflections on the Painting and Sculpture of the Greeks influenced European taste for the next half-century. Greek sculpture was (as it still is) known almost exclusively through Roman copies, and the striving for the cool, serene and noble sentiments that art seemed to embody is exemplified most of all by the work of Antonio Canova, represented by his marble statue of Apollo crowning himself.

Ancient carved gemstones and cameos, cameo casts, contemporary gemstones carved in the manner of ancient ones, prints, and a painting by Canaletto, The Arch of Constantine with the Colosseum in the background, show how works of art served as souvenirs and aide-memoires for returning visitors. Ultimately, their patronage and spending was the driving force behind Neo-classicism, the international style that wedded the principles of ancient art to modern individual inventiveness.

Collecting of an entirely different sort and on an entirely different scale marked the end of the Grand Tour and of aristocratic classical taste. Napoleon’s invasion of Italy signaled the beginning of the end of the aristocratic age for which Italy was both the goal and the source.

See also: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Years in Vienna

- the Grand Tour

Austerity Measures And a Vintage Celebrity

Unmissable events—eccentric, regal and random.

Related Posts

The Educated Traveller

History of the grand tour .

In the early years of the 18th and 19th centuries it was fashionable, for wealthy British families, to send their son and heir on a tour of Europe. A trip that was designed to introduce the young ‘ milord ‘ to the art, history and culture of Italy. The British educational system was based on Latin and Greek literature and philosophy. An educated person was taught the classics from a very early age. Whilst the original Grand Tourists were mostly male, there were a few enlightened families who sent their daughters to ‘the continent’ too. Aristocratic families regarded this journey to Europe as an opportunity to complete their education. The journey was known as the ‘Grand Tour’. The young gentlemen and a few ladies were often accompanied by a ‘learned guide’ a person who could act as a tutor and chaperone. These guides, usually highly educated, were known in Italian as ‘ cicerone’ and it was their job to explain the history, art and literature of Italy to their young charges.

A ‘Grand Tour’ generally included visits to Rome, Naples, Venice and Florence. On the journey south Geneva or Montreux in Switzerland were popular stopping off points too. Think Daisy Miller in Henry James novella of the same name. Wealthy families traversed Europe, often for months on end, absorbing every possible palace, party and picnic in the process. For many it was a very long and decadent party for others it was a necessary departure from their homeland until the dust of a divorce, bankruptcy or other social scandal had settled.

THE JOURNEY – Young gentlemen would make the journey south from The British Isles, either by ship or overland by horse and carriage. There are numerous reports of these young travellers being made chronically ill by travel sickness, rough seas and ‘foreign food’. In the 1730s and 1740s roads were rough and full of potholes, carriages could expect to cover a maximum of 15-20 miles per day. Highwaymen and groups of brigands often preyed on travellers, hoping to steal money and jewels. In the days of the ‘Grand Tour’ travel wasn’t for the faint-hearted . Crossing the Alps was a particular challenge. Depending on the age and level of fitness of travellers, it may have been necessary to hire a sedan chair to be carried, literally, by strong local men over various Alpine passes. In fact the ‘chairmen of Mont Cenis’ close to Val d’Isere were known throughout the Alps for their strength and dexterity. These ‘chair carriers’ worked in pairs and groups of four, six or even eight men – they physically carried the ‘Grand Tourists’ over the Alps.

TRAVELLING – Having endured a crossing of the Alps the young ‘milordi’ would head to Milan or Turin where the local British consulate would offer a warm welcome. However, the really attractive destinations were further away, particularly Venice, Florence, Rome and Naples. These cities were renowned for their entertainment, lavish parties and sense of fun. There’s a fantastic cartoon, by David Allen (above) showing a young aristocrat arriving in Piazza di Spagna, Rome. His carriage is instantly surrounded by local touts, street performers, actors and actresses, all anxious to separate young ‘Algernon’ from his trunk full of cash! It’s interesting to remember that the Italians have been welcoming tourists to their lands for centuries. They’ve learned a thing or two about helping newly arrived foreigners!

VENICE – In Venice the British Consul Joseph Smith was an art collector and supporter of local artists. Smith lived in a small palace on the Grand Canal, filled with paintings, art, books and coins. He was patron of Canaletto, probably the most famous and popular Venetian painter of his day. Canaletto painted ‘vedute’ scenes of Venice. Every Grand Tourist wanted to leave with a Canaletto painting as a souvenir of the Grand Tour. Smith’s art collection was so impressive that a young King George III purchased the entire collection in 1762, when he was himself on the Grand Tour. So Joseph Smith’s art collection became the basis of the British ‘Royal Collection’ of art much of which can still be seen at Buckingham Palace or in the National Gallery, London today. Whilst in Venice the young Grand Tourists would attend concerts, visit churches and wherever possible attend a ball or two. Venice at Carnival time was a particular fascination – an opportunity to put on a mask and be whoever you wanted to be!

A typical Grand Tour of Europe could last up to two years and would always include several months staying in each city visited.

Florence was popular for its renaissance art, magnificent country villas and gardens, whilst Rome was essential for proper, classical, ancient ruins. Venice was the party city, especially at the time of Carnival. Naples was regarded as the home of archaeology, excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum began in the 1730s and Vesuvius was quite active at this time. Plumes of volcanic gases and occasional lava flows would illuminate the mountain after dark. The Grand Tourists would position themselves on the lower slopes of the volcano to watch the nightly spectacle.

IN ROME – many of the Grand Tourists funded excavation work in and around the Roman Forum and the Colosseum. Many of the Grand Tourists wanted to acquire a Roman statue or sculpture to take home as a souvenir. There were numerous stonemasons working in and around the basement of the Colosseum, creating modern and ‘antique’ marble sculptures. Even in the 18th century demand exceeded supply in the ‘genuine Roman sculpture market’. Many Grand Tourists left for home with an ‘original’ antique Roman statue, which years later, under expert examination turned out to be a fake! The artist Panini painted several imaginary compositions of young Grand Tourists surrounded by paintings of Roman buildings and ruins. Each of the ‘ruins’ in the paintings was based on an actual Roman building. For example, in the painting below The Pantheon is clearly visible just to the right of the two standing gentlemen. Above the Pantheon is the Colosseum. On the left of the painting above the two seated gentlemen the Roman arches of Constantine and Septimius Severus can be seen.

Roma Antica – by Giovanni Paolo Pannini c. 1754 – Stuttgart Art Museum

The Grand Tour inspired many travellers to take a greater interest in Roman history and art. The study of archaeology was born at this time with extensive excavations taking place in Pompeii, Herculaneum and in the area of the Roman Forum in Rome. The British School at Rome was established to learn more about the Roman ruins and to fund excavations. The School still exists today. Below is another painting by Pannini showing the wonders of Modern Rome (1750s) – featuring details of Baroque fountains, palaces and elegant piazzas. These exceptionally detailed paintings effectively catalogue the ‘ancient marbles’ discovered in Italy by the middle years of the 18th century.

NAPLES – for fun and excitement on the Grand Tour was very popular. Lord Hamilton, British Ambassador in Naples was a wonderful host and put on spectacular parties and musical evenings. His second wife Emma Hamilton would dress in Roman and Greek style clothing and perform a series of ‘Attitudes’ where guests had to guess her identity. It was here at the Hamilton residence that Emma attracted the attention of Lord Nelson, British naval hero of the day, and they became lovers.

Meanwhile Vesuvius , the volcano that dominates the Bay of Naples was having an active phase in the 1760s and 1770s, most days steam could be seen rising from the crater and frequently, especially after nightfall, streams of glowing lava could be observed. Lord Hamilton wrote several articles on Vesuvius and the lava flows that he witnessed. Many visiting painters were inspired to paint Vesuvius and the surrounding area. The science of vulcanology was in its infancy. The spectacle that Vesuvius offered visitors most nights must have seemed quite extraordinary to the early Grand Tourists – typically away from home in strange and different lands for the first time.

From Naples it was relatively easy to arrange transport on a British ship back to England. So Naples was a popular end point for the 18th century Grand Tour. The young aristocrats would board a ship bound for England and assuming no rough seas they’d be home within a few weeks. Typically they’d have extensive luggage including marble statues and friezes from Rome, paintings and glassware from Venice, even lava samples and pumice stone from Naples . All these souvenirs would be displayed with great pride in the family home. The impact on British country houses of the Grand Tour can still be seen today. Almost every stately home in Britain has several paintings by Canaletto, commissioned during the Grand Tour. Many stately homes have a sculpture gallery, often specially built to accommodate the Roman statues and marble work brought back from the Grand Tour.

In a sense the Grand Tour was the start of modern tourism, it was a journey taken to learn and experience new and different styles of art, architecture and culture. A journey designed to understand and learn about Europe. The Grand Tour was a couple of years enjoying the best that Europe (especially Italy) had to offer. Parties, ladies, fine food and wine – and family members at a distance – a letter from mama or papa would take weeks to arrive. The young aristocrats had freedom, fun, sun and souvenirs. What finer way to complete a young gentleman’s education. Head home with a sack full of souvenirs and a full and varied experience of life – this was escapism at its best!

- ‘Milordi’ is a term referring to aristocratic men, literally meaning ‘my lords’. In the days of the Grand Tour the term ‘milordi’ was an ironic and satirical way of referring to young, aristocratic men, travelling in Europe with (generally speaking) more money than sense.

- Cicerone or bear-leader was a popular term for a man who escorted young men of rank or wealth on their travels on the Grand Tour . The role of cicerone or bear-leader blended elements of tutor, chaperone and companion. These tutor-companions were often hired to keep the young ‘milordi’ out of trouble and to ensure that they didn’t do anything to embarrass their families. The name Cicerone originally comes from ‘Cicero’ referring to the famous Roman orator, politician, thinker and writer., who lived from 106-43 BC.

Many of London’s museums have exceptional collections of Italian and Greek paintings and sculptures as a result of the Grand Tour. The National Gallery has an amazing collection: https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/learn-about-art/paintings-in-depth/the-grand-tour

- I’ve written about Herculaneum at the time of the eruption of Vesuvius in 79AD.

- I’ve also written other articles about Naples and Herculaneum:

- Herculaneum – a very bright future…..

- Naples, A Crazy Prince and fantastic pizza…

- To learn more about unique travel opportunities and tailor-made journeys check out our sister web site: Grand Tourist for ideas and examples of exceptional travel experiences.

- The picture at the top of this article (reproduced below) is by German 19th century painter Carl Spitzweg. It is a wonderful, and humorous portrayal of earnest English tourists soaking in the atmosphere at a ruined temple site (it could be Paestum, south of Naples). Although I think it might be Agrigento, Sicily. The artist has captured the mood of the ‘Grand Tourists’, just look carefully at the characters!

Herculaneum, Roman seaside town, buried by eruption of Vesuvius 79 AD (left). Map (right) shows areas excavated by 1908

- NOTE: Journeys in Europe are designed by our sister company www.grand-tourist.com drop us a line to discuss your perfect grand tour.

- Written: 23-11-17

- Updated: 15-11-20 / 10-01-2022 / 10-12-2023

#grandtour #grandtourist #educatedtraveller #archaeology

Please share this:

30 thoughts on “ history of the grand tour ”.

So THIS is where the name for your tour company originated! I feel like a GRAND TOURIST when I’m traveling with you, Janet–learning as I travel just like the folks from centuries ago! Thanks for this terrific background article!

Like Liked by 1 person

I was going to say the same as Mary Lou Peters, and congratulate you on your four bears (Darn that predictive text – I had actually dictated “congratulate you on your forebears”!) – A truly riveting and informative article – superb reading – thank you so much for that!

Thank you John – appreciated!

- Pingback: Vesuvius – volcanic eruption, Herculaneum & Pompeii – The Educated Traveller

- Pingback: My favourite London museum – The Educated Traveller

- Pingback: Herculaneum – a bright future in 2018 – The Educated Traveller

- Pingback: Rome – the eternal city – The Educated Traveller

- Pingback: Canaletto and Venice – The Educated Traveller

- Pingback: Rome – There’s so much to see at the city gates – The Educated Traveller

- Pingback: Crossing the Alps in style – The Educated Traveller

- Pingback: The best chocolate in Italy – The Educated Traveller

- Pingback: New Year – Neuchâtel – New Thinking – The Educated Traveller

- Pingback: Art can make you laugh… – The Educated Traveller

- Pingback: Paestum – Greek Temples, Tomb Paintings & Ristorante Nettuno – The Educated Traveller

Excellent, enjoyably breezy summary of a very important 18th century phenomenon, really enjoyed it, thank you.

Hi Arran – thank you so much for this kind comment. I’m delighted you enjoyed my summary!

- Pingback: Venice – happy to be back… – The Educated Traveller

Hello Miss Onion – thanks for finding my blog. Please can you put the source as educated-traveller.com Thank you. Also the book about the Grand Tour is by Brian Dolan (Katie Hickman just wrote a review) If you want a little more background on the Grand Tour just ask – I run a travel business called Grand Tourist as well as writing my blog! Have a good day.

- Pingback: An English Country House – The Educated Traveller

- Pingback: Gap Years and the Singaporean Dream - Hype Singapore

- Pingback: Venice – Casanova, Casinos & Canaletto – The Educated Traveller

- Pingback: Venice – Carnival 2020 – The Educated Traveller

Thanks for linking to my ‘History of the Grand Tour’. Curiously I too was an undergraduate at Oxford, although not one of the drunken ones. Were you a Rhodes or a Fulbright Scholar? The authors who wrote for the original Grand Tourists were people like John Murray and Baedeker. In fact you couldn’t call yourself a serious ‘tourist’ without a small red volume of either writer tucked under your arm!

Absolutely amazing piece. Thank you for providing such interesting information!

Thank you Natalia x

Thank you for including my article in your list. I am fascinated by the Grand Tour – possibly Adam Smith’s decision to leave his post and become a private tutor, meandering around Europe, was not such an unusual one. Certainly the Italian cities of Venice, Florence, Rome and Naples were filled with eager ‘tourists’ anxious to learn and often to finance restoration of ancient buildings. It must have been a very interesting time.

- Pingback: What Was the Grand Tour? – Kat Devitt

Leave a comment Cancel reply