- Skip to main content

- Skip to "About government"

Language selection

- Français

The second voyage (1535-1536)

Cartier-brébeuf national historic site.

The following year, his ships filled with provisions for a 15-month expedition, Jacques Cartier explored both shores of the St. Lawrence River beginning from Anticosti Island. He was aided in this endeavour by the two Amerindians he had captured during the previous voyage. On September 7, 1535, he dropped anchor on the north side of Île d'Orléans. Domagaya and Taignoagny, who had become Cartier's guides in these territories, now returned to their homeland and introduced Cartier to the people of Stadacona. The explorer offered the Amerindians presents. This meeting of the two peoples was a cause for numerous celebrations.

Not long after arriving at Île d'Orléans, Jacques Cartier decided to explore the surrounding country for the purpose of finding a suitable location in which to shelter his vessels. He discovered a natural haven at the junction of the Lairet and Saint-Charles Rivers. It was a particularly advantageous setting, as it prevented the ships from being dragged away by tides, and the surrounding hillsides provided shelter from wind. The explorer declared himself satisfied with the location, which was to become the present-day Cartier-Brébeuf National Historic Site, and had his two largest ships, the Grande Hermine and the Petite Hermine, cast anchor for the winter.

Cartier then began laying plans for travel upriver to Hochelaga (present-day Montréal). Domagaya and Taignoagny attempted to dissuade him from this course of action, and then flatly refused to accompany him. They thereby hoped to reserve the benefits of trading with the Europeans for the inhabitants of Stadacona alone. Despite the ruses and threats of the Amerindians, Cartier set out on his expedition aboard the Émérillion on September 19. The inhabitants of Hochelaga provided him a warm welcome. As no interpreters were to be had, the Europeans and the Amerindians had to use sign language. The French navigator developed the impression that there was gold beyond the Lachine rapids. He thus vowed to continue his exploration at some future date.

Related links

- The great explorations

- The first voyage (1534)

- Wintering (1535-1536)

- The third voyage (1541-1542)

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

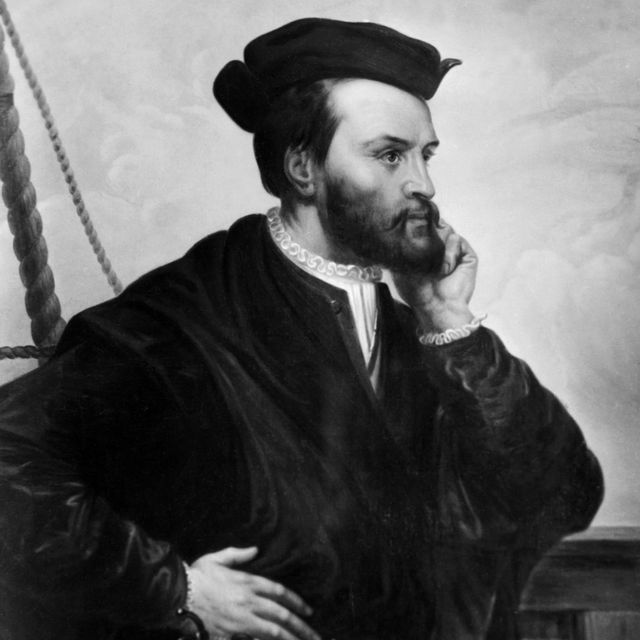

Jacques Cartier

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 6, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

In 1534, France’s King Francis I authorized the navigator Jacques Cartier to lead a voyage to the New World in order to seek gold and other riches, as well as a new route to Asia. Cartier’s three expeditions along the St. Lawrence River would later enable France to lay claim to the lands that would become modern-day Canada. He gained a reputation as a skilled navigator prior to making his three famous voyages to North America.

Jacques Cartier’s First North American Voyage

Born December 31, 1491, in Saint-Malo, France, Cartier began sailing as a young man. He was believed to have traveled to Brazil and Newfoundland—possibly accompanying explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano —before 1534.

That year, the government of King Francis I of France commissioned Cartier to lead an expedition to the “northern lands,” as the east coast of North America was then known. The purpose of the voyage was to find a northwest passage to Asia, as well as to collect riches such as gold and spices along the way.

Did you know? In addition to his exploration of the St. Lawrence region, Jacques Cartier is credited with giving Canada its name. He reportedly misused the Iroquois word kanata (meaning village or settlement) to refer to the entire region around what is now Quebec City; it was later extended to the entire country.

Cartier set sail in April 1534 with two ships and 61 men, and arrived 20 days later. During that first expedition, he explored the western coast of Newfoundland and the Gulf of St. Lawrence as far as today’s Anticosti Island, which Cartier called Assomption. He is also credited with the discovery of what is now known as Prince Edward Island.

Cartier’s Second Voyage

Cartier returned to make his report of the expedition to King Francis, bringing with him two captured Native Americans from the Gaspé Peninsula. The king sent Cartier back across the Atlantic the following year with three ships and 110 men. With the two captives acting as guides, the explorers headed up the St. Lawrence River as far as Quebec, where they established a base camp.

The following winter wrought havoc on the expedition, with 25 of Cartier’s men dying of scurvy and the entire group incurring the anger of the initially friendly Iroquois population. In the spring, the explorers seized several Iroquois chiefs and traveled back to France.

Though he had not been able to explore it himself, Cartier told the king of the Iroquois’ accounts of another great river stretching west, leading to untapped riches and possibly to Asia.

Cartier’s Third and Final Voyage

War in Europe stalled plans for another expedition, which finally went forward in 1541. This time, King Francis charged the nobleman Jean-François de La Rocque de Roberval with founding a permanent colony in the northern lands. Cartier sailed a few months ahead of Roberval, and arrived in Quebec in August 1541.

After enduring another harsh winter, Cartier decided not to wait for the colonists to arrive, but sailed for France with a quantity of what he thought were gold and diamonds, which had been found near the Quebec camp.

Along the way, Cartier stopped in Newfoundland and encountered Roberval, who ordered Cartier to return with him to Quebec. Rather than obey this command, Cartier sailed away under cover of night. When he arrived back in France, however, the minerals he brought were found to have no value.

Cartier received no more royal commissions, and would remain at his estate in Saint-Malo, Brittany, for the rest of his life. He died there on September 1, 1557. Meanwhile, Roberval’s colonists abandoned the idea of a permanent settlement after barely a year, and it would be more than 50 years before France again showed interest in its North American claims.

Jacques Cartier. The Mariner’s Museum and Park . The Explorers: Jacques Cartier 1534-1542. Canadian Museum of History .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Second Voyage of Jaques Cartier

Jacques Cartier's second voyage to the New World commenced on May 19, 1535, a little more than a year after his return from his initial expedition. This time, Cartier commanded a flotilla of three ships—the Grande Hermine, the Petite Hermine, and the Émérillon—with a crew totaling around 110 men. His main objective remained the same: to find a westward route to Asia that would allow France to participate in the lucrative spice trade.

Setting sail from St. Malo, France, Cartier and his fleet made their way across the Atlantic Ocean, guided by two Iroquois sons of Chief Donnacona, Domagaya and Taignoagny, who had returned from France for this expedition. Arriving in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Cartier followed the St. Lawrence River, a waterway he hoped would serve as a route to Asia. Instead, the river led him deep into the North American continent.

In early September, the expedition reached what is now Quebec City. Cartier then continued to venture upstream and arrived at a native village named Stadacona, near present-day Quebec City. He also made his way to another settlement called Hochelaga, situated at the site of modern-day Montreal. Here, he scaled a hill and named it Mont Royal, providing the inspiration for the city's eventual name.

Despite the warm initial reception from the native people, relations soon deteriorated, particularly with Chief Donnacona. With the harsh winter closing in, Cartier decided to winter at Stadacona. His crew suffered from scurvy, a disease they were unprepared for, and many men died. It was only through the knowledge of the native people, who showed them how to prepare a concoction from a local tree (likely the white cedar), that they managed to combat the illness.

By spring, Cartier realized that the St. Lawrence River was not the passage to Asia he had hoped for. Frustrated and low on supplies, he decided to return to France. Before leaving, Cartier kidnapped Chief Donnacona and several other natives to take back to France as proof of his discoveries. These actions further strained relations between the French and the indigenous populations.

Cartier returned to France in July 1536, his ships laden with what he believed to be gold and diamonds but were later discovered to be iron pyrite and quartz, respectively. Despite failing to find a route to Asia or the wealth he had anticipated, Cartier's voyages laid the foundation for future French claims in North America and contributed to geographical knowledge of the continent.

Jacques Cartier

French explorer Jacques Cartier is known chiefly for exploring the St. Lawrence River and giving Canada its name.

(1491-1557)

Who Was Jacques Cartier?

French navigator Jacques Cartier was sent by King Francis I to the New World in search of riches and a new route to Asia in 1534. His exploration of the St. Lawrence River allowed France to lay claim to lands that would become Canada. He died in Saint-Malo in 1557.

Early Life and First Major Voyage to North America

Born in Saint-Malo, France on December 31, 1491, Cartier reportedly explored the Americas, particularly Brazil, before making three major North American voyages. In 1534, King Francis I of France sent Cartier — likely because of his previous expeditions — on a new trip to the eastern coast of North America, then called the "northern lands." On a voyage that would add him to the list of famous explorers, Cartier was to search for gold and other riches, spices, and a passage to Asia.

Cartier sailed on April 20, 1534, with two ships and 61 men, and arrived 20 days later. He explored the west coast of Newfoundland, discovered Prince Edward Island and sailed through the Gulf of St. Lawrence, past Anticosti Island.

Second Voyage

Upon returning to France, King Francis was impressed with Cartier’s report of what he had seen, so he sent the explorer back the following year, in May, with three ships and 110 men. Two Indigenous peoples Cartier had captured previously now served as guides, and he and his men navigated the St. Lawrence, as far as Quebec, and established a base.

In September, Cartier sailed to what would become Montreal and was welcomed by the Iroquois who controlled the area, hearing from them that there were other rivers that led farther west, where gold, silver, copper and spices could be found. Before they could continue, though, the harsh winter blew in, rapids made the river impassable, and Cartier and his men managed to anger the Iroquois.

So Cartier waited until spring when the river was free of ice and captured some of the Iroquois chiefs before again returning to France. Because of his hasty escape, Cartier was only able to report to the king that untold riches lay farther west and that a great river, said to be about 2,000 miles long, possibly led to Asia.

Third Voyage

In May 1541, Cartier departed on his third voyage with five ships. He had by now abandoned the idea of finding a passage to the Orient and was sent to establish a permanent settlement along the St. Lawrence River on behalf of France. A group of colonists was a few months behind him this time.

Cartier set up camp again near Quebec, and they found an abundance of what they thought were gold and diamonds. In the spring, not waiting for the colonists to arrive, Cartier abandoned the base and sailed for France. En route, he stopped at Newfoundland, where he encountered the colonists, whose leader ordered Cartier back to Quebec. Cartier, however, had other plans; instead of heading to Quebec, he sneaked away during the night and returned to France.

There, his "gold" and "diamonds" were found to be worthless, and the colonists abandoned plans to found a settlement, returning to France after experiencing their first bitter winter. After these setbacks, France didn’t show any interest in these new lands for half a century, and Cartier’s career as a state-funded explorer came to an end. While credited with the exploration of the St. Lawrence region, Cartier's reputation has been tarnished by his dealings with the Iroquois and abandonment of the incoming colonists as he fled the New World.

Cartier died on September 1, 1557, in Saint-Malo, France.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Jacques Cartier

- Birth Year: 1491

- Birth date: December 31, 1491

- Birth City: Saint-Malo, Brittany

- Birth Country: France

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: French explorer Jacques Cartier is known chiefly for exploring the St. Lawrence River and giving Canada its name.

- Astrological Sign: Capricorn

- Nacionalities

- Death Year: 1557

- Death date: September 1, 1557

- Death City: Saint-Malo, Brittany

- Death Country: France

- If the soil were as good as the harbors, it would be a blessing.

- [T]he land should not be called the New Land, being composed of stones and horrible rugged rocks; for along the whole of the north shore I did not see one cartload of earth and yet I landed in many places.

- Out of 110 that we were, not 10 were well enough to help the others, a thing pitiful to see.

- Today was our first day at sea. The weather was good, no clouds at the horizon and we are praying for a smooth sail.

- We set sail again trying to discover more wonders of this new world.

- Today I did something great for my country. We have taken over the land. Long live the King of France!

- I'm anxious to see what lies ahead. Every day we are getting deeper and deeper inside the continent, which increases my curiosity.

- Today I have completed my second voyage, which I can say had thought me a lot about how different things are in this world and how people start building up communities according to their common beliefs.

- The world is big and still hiding a lot.

- There arose such stormy and raging winds against us that we were constrained to come to the place again from whence we were come.

- I am inclined to believe that this is the land God gave to Cain.

Watch Next .css-smpm16:after{background-color:#323232;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

In this Book

- With an introduction by Ramsay Cook

- Published by: University of Toronto Press

Jacques Cartier's voyages of 1534, 1535, and 1541constitute the first record of European impressions of the St Lawrence region of northeastern North American and its peoples. The Voyages are rich in details about almost every aspect of the region's environment and the people who inhabited it.

In addition to Cartier's Voyages , a slightly amended version of H.P. Biggar's 1924 text, the volume includes a series of letters relating to Cartier and the Sieur de Roberval, who was in command of cartier on the last voyage. Many of these letters appear for the first time in English.

Ramsay Cook's introduction, 'Donnacona Discovers Europe,' rereads the documents in the light of recent scholarship as well as from contemporary perspectives in order to understand better the viewpoints of Cartier and the native people with whom he came into contact.

Table of Contents

- Title Page, Copyright Page

- pp. vii-viii

- Donnacona Discovers Europe: Rereading Jacques Cartier's Voyages

- The Voyages

- Cartier's First Voyage, 1534

- Cartier's Second Voyage, 1535-1536

- Cartier's Third Voyage, 1541

- Roberval's Voyage, 1542-1543

- pp. 107-113

- Documents relating to Jacques Cartier and the Sieur de Roberval

- 1 Grant of Money to Cartier for His First Voyage

- 2 Commission from Admiral Chabot to Cartier

- 3 Choice of Vessels for the Second Voyage

- pp. 119-120

- 4 Payment of Three Thousand Livres to Cartier for His Second Voyage

- 5 Roll of the Crews for Cartier's Second Voyage

- pp. 122-124

- 6 Order from King Francis the First for the Payment to Cartier of Fifty Crowns

- 7 List of Men and Effects for Canada

- pp. 126-129

- 8 Letter from Lagarto to John the Third, King of Portugal

- pp. 130-133

- 9 The Baptism of the Savages from Canada

- 10 Cartier's Commission for His Third Voyage

- pp. 135-138

- 11 Letters Patent from the Duke of Brittany Empowering Cartier to Take Prisoners from the Gaols

- pp. 139-140

- 12 The Emperor to the Cardinal of Toledo

- pp. 141-142

- 13 An Order from King Francis to Inquire into the Hindrances Placed before Cartier

- 14 Roberval's Commission

- pp. 144-151

- 15 Secret Report on Cartier's Expedition

- pp. 152-155

- 16 Cartier's Will

- pp. 156-158

- 17 Examination of Newfoundland Sailors regarding Cartier

- pp. 159-168

- 18 Cartier Takes Part in a 'Noise'

- pp. 169-170

- 19 Statement of Cartier's Account

- pp. 171-176

- 20 Death of Cartier

Additional Information

Project muse mission.

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

CHAPTER IV. THE SECOND VOYAGE - THE ST LAWRENCE

- Stephen Leacock

The second voyage of Jacques Cartier, undertaken in the years 1535 and 1536, is the exploit on which his title to fame chiefly rests. In this voyage he discovered the river St Lawrence, visited the site of the present city of Quebec, and, ascending the river as far as Hochelaga, was enabled to view from the summit of Mount Royal the imposing panorama of plain and river and mountain which marks the junction of the St Lawrence and the Ottawa. He brought back to the king of France the rumour of great countries still to be discovered to the west, of vast lakes and rivers reaching so far inland that no man could say from what source they sprang, and the legend of a region rich with gold and silver that should rival the territory laid at the feet of Spain by the conquests of Cortez. If he did not find the long-sought passage to the Western Sea, at least he added to the dominions of France a territory the potential wealth of which, as we now see, was not surpassed even by the riches of Cathay.

The report of Cartier's first voyage, written by himself, brought to him the immediate favour of the king. A commission, issued under the seal of Philippe Chabot, admiral of France, on October 30, 1534, granted to him wide powers for employing ships and men, and for the further prosecution of his discoveries. He was entitled to engage at the king's charge three ships, equipped and provisioned for fifteen months, so that he might be able to spend, at least, an entire year in actual exploration. Cartier spent the winter in making his preparations, and in the springtime of the next year (1535) all was ready for the voyage.

By the middle of May the ships, duly manned and provisioned, lay at anchor in the harbour of St Malo, waiting only a fair wind to sail. They were three in number - the Grande Hermine of 120 tons burden; a ship of 60 tons which was rechristened the Petite Hermine, and which was destined to leave its timbers in the bed of a little rivulet beside Quebec, and a small vessel of 40 tons known as the Emerillon or Sparrow Hawk. On the largest of the ships Cartier himself sailed, with Claude de Pont Briand, Charles de la Pommeraye, and other gentlemen of France, lured now by a spirit of adventure to voyage to the New World. Mace Jalobert, who had married the sister of Cartier's wife, commanded the second ship. Of the sailors the greater part were trained seamen of St Malo. Seventy-four of their names are still preserved upon a roll of the crew. The company numbered in all one hundred and twelve persons, including the two savages who had been brought from Gaspe in the preceding voyage, and who were now to return as guides and interpreters of the expedition.

Whether or not there were any priests on board the ships is a matter that is not clear. The titles of two persons in the roll - Dom Guillaume and Dom Antoine - seem to suggest a priestly calling. But the fact that Cartier made no attempt to baptize the Indians to whom he narrated the truths of the Gospel, and that he makes no mention of priests in connection with any of the sacred ceremonies which he carried out, seem to show that none were included in the expedition. There is, indeed, reference in the narrative to the hearing of mass, but it relates probably to the mere reading of prayers by the explorer himself. On one occasion, also, as will appear, Cartier spoke to the Indians of what his priests had told him, but the meaning of the phrase is doubtful.

Before sailing, every man of the company repaired to the Cathedral Church of St Malo, where all confessed their sins and received the benediction of the good bishop of the town. This was on the day and feast of Pentecost in 1535, and three days later, on May 19, the ships sailed out from the little harbour and were borne with a fair wind beyond the horizon of the west. But the voyage was by no means as prosperous as that of the year before. The ships kept happily together until May 26. Then they were assailed in mid-Atlantic by furious gales from the west, and were enveloped in dense banks of fog. During a month of buffeting against adverse seas, they were driven apart and lost sight of one another.

Cartier in the Grande Hermine reached the coast of Newfoundland safely on July coming again to the Island of Birds. 'So full of birds it was,' he writes, 'that all the ships of France might be loaded with them, and yet it would not seem that any were taken away.' On the next day the Grande Hermine sailed on through the Strait of Belle Isle for Blanc Sablon, and there, by agreement, waited in the hope that her consorts might arrive. In the end, on the 26th, the two missing ships sailed into the harbour together. Three days more were spent in making necessary repairs and in obtaining water and other supplies, and on the 29th at sunrise the reunited expedition set out on its exploration of the northern shore. During the first half of August their way lay over the course already traversed from the Strait of Belle Isle to the western end of Anticosti. The voyage along this coast was marked by no event of especial interest. Cartier, as before, noted carefully the bearing of the land as he went along, took soundings, and, in the interest of future pilots of the coast, named and described the chief headlands and landmarks as he passed. He found the coast for the most part dangerous and full of shoals. Here and there vast forests extended to the shore, but otherwise the country seemed barren and uninviting.

From the north shore Cartier sailed across to Anticosti, touching near what is now called Charleton Point; but, meeting with head winds, which, as in the preceding year, hindered his progress along the island, he turned to the north again and took shelter in what he called a 'goodly great gulf full of islands, passages, and entrances towards what wind soever you please to bend.' It might be recognized, he said, by a great island that runs out beyond the rest and on which is 'an hill fashioned as it were an heap of corn.' The 'goodly gulf' is Pillage Bay in the district of Saguenay, and the hill is Mount Ste Genevieve.

From this point the ships sailed again to Anticosti and reached the extreme western cape of that island. The two Indian guides were now in a familiar country. The land in sight, they told Cartier, was a great island; south of it was Gaspe, from which country Cartier had taken them in the preceding summer; two days' journey beyond the island towards the west lay the kingdom of Saguenay, a part of the northern coast that stretches westwards towards the land of Canada. The use of this name, destined to mean so much to later generations, here appears for the first time in Cartier's narrative. The word was evidently taken from the lips of the savages, but its exact significance has remained a matter of dispute. The most fantastic derivations have been suggested. Charlevoix, writing two hundred years later, even tells us that the name originated from the fact that the Spaniards had been upon the coast before Cartier, looking for mines. Their search proving fruitless, they kept repeating 'aca nada' (that is 'nothing here') in the hearing of the savages, who repeated the words to the French, thus causing them to suppose this to be the name of the country. There seems no doubt, however, that the word is Indian, though whether it is from the Iroquois Kannata, a settlement, or from some term meaning a narrow strait or passage, it is impossible to say.

From Anticosti, which Cartier named the Island of the Assumption, the ships sailed across to the Gaspe side of the Gulf, which they saw on August 16, and which was noted to be a land 'full of very great and high hills.' According to the information of his Indian guides, he had now reached the point beyond which extended the great kingdom of Saguenay. The northern and southern coasts were evidently drawing more closely together, and between them, so the savages averred, lay a great river.

'There is,' wrote Cartier in his narrative, 'between the southerly lands and the northerly about thirty leagues distance and more than two hundred fathoms depth. The said men did, moreover, certify unto us that there was the way and beginning of the great river of Hochelaga, and ready way to Canada, which river the farther it went the narrower it came, even unto Canada, and that then there was fresh water which went so far upwards that they had never heard of any man who had gone to the head of it, and that there is no other passage but with small boats.'

The announcement that the waters in which he was sailing led inward to a fresh-water river brought to Cartier not the sense of elation that should have accompanied so great a discovery, but a feeling of disappointment. A fresh-water river could not be the westward passage to Asia that he had hoped to find, and, interested though he might be in the rumoured kingdom of Saguenay, it was with reluctance that he turned from the waters of the Gulf to the ascent of the great river. Indeed, he decided not to do this until he had tried by every means to find the wished-for opening on the coast of the Gulf. Accordingly, he sailed to the northern shore and came to the land among the Seven Islands, which lie near the mouth of the Ste Marguerite river, about eighty-five miles west of Anticosti, - the Round Islands, Cartier called them. Here, having brought the ships to a safe anchorage, riding in twenty fathoms of water, he sent the boats eastward to explore the portion of the coast towards Anticosti which he had not yet seen. He cherished a last hope that here, perhaps, the westward passage might open before him. But the boats returned from the expedition with no news other than that of a river flowing into the Gulf, in such volume that its water was still fresh three miles from the shore. The men declared, too, that they had seen 'fishes shaped like horses,' which, so the Indians said, retired to shore at night, and spent the day in the sea. The creatures, no doubt, were walruses.

It was on August 15 that Cartier had left Anticosti for the Gaspe shore: it was not until the 24th that, delayed by the exploring expeditions of the boats and by heavy fogs and contrary winds, he moved out from the anchorage at the Seven Islands to ascend the St Lawrence. The season was now far advanced. By this time, doubtless, Cartier had realized that the voyage would not result in the discovery of the passage to the East. But, anxious not to return home without having some success to report, he was in any case prepared to winter in the New Land. Even though he did not find the passage, it was better to remain long enough to explore the lands in the basin of the great river than to return home without adding anything to the exploits of the previous voyage.

The expedition moved westward up the St Lawrence, the first week's sail bringing them as far as the Saguenay. On the way Cartier put in at Bic Islands, and christened them in honour of St John. Finding here but scanty shelter and a poor anchorage, he went on without further delay to the Saguenay, the mouth of which he reached on September 1. Here this great tributary river, fed from the streams and springs of the distant north, pours its mighty waters between majestic cliffs into the St Lawrence - truly an impressive sight. So vast is the flood that the great stream in its wider reaches shows a breadth of three miles, and in places the waters are charted as being more than eight hundred and seventy feet deep. Narrowing at its mouth, it enters the St Lawrence in an angry flood, shortly after passing the vast and frowning rocks of Cape Eternity and Cape Trinity, rising to a height of fifteen hundred feet. High up on the face of the cliffs, Cartier saw growing huge pine-trees that clung, earthless, to the naked rock. Four canoes danced in the foaming water at the river mouth: one of them made bold to approach the ships, and the words of Cartier's Indian interpreters so encouraged its occupants that they came on board. The canoes, so these Indians explained to Cartier, had come down from Canada to fish.

Cartier did not remain long at the Saguenay. On the next day, September 2, the ships resumed their ascent of the St Lawrence. The navigation at this point was by no means easy. The river here feels the full force of the tide, whose current twists and eddies among the great rocks that lie near the surface of the water. The ships lay at anchor that night off Hare Island. As they left their moorings, at dawn of the following day, they fell in with a great school of white whales disporting themselves in the river. Strange fish, indeed, these seemed to Cartier. 'They were headed like greyhounds,' he wrote, 'and were as white as snow, and were never before of any man seen or known.'

Four days more brought the voyagers to an island, a 'goodly and fertile spot covered with fine trees,' and among them so many filbert-trees that Cartier gave it the name Isle-aux-Coudres (the Isle of Filberts), which it still bears. On September 7 the vessels sailed about thirty miles beyond Isle-aux-Coudres, and came to a group of islands, one of which, extending for about twenty miles up the river, appeared so fertile and so densely covered with wild grapes hanging to the river's edge, that Cartier named it the Isle of Bacchus. He himself, however, afterwards altered the name to the Island of Orleans. These islands, so the savages said, marked the beginning of the country known as Canada.

- Popular Books

- Popular Pages

- Adventures in the Unknown Interior of America

- From Normandy to the Pyrénées

- In the Heart of Africa

- Château and Country Life in France

- Tent Life in Siberia

- Among the Tibetans

- Canyons of the Colorado

- In The Amazon Jungle

- A Voyage in the 'Sunbeam'

- American Encyclopedia - Travel

- THE COLOSSEUM AND THE FORUM

- Captain James Cook

- THE DAWN OF A CENTURY OF DISCOVERY

- CHAPTER II. Narrative of Captain Cook's first voyage round the world.

- CHAPTER IV. Narrative of Captain Cook's second Voyage round the World.

- FRENCH NAVIGATORS, I

- Travels in Africa. Park, Denham, Clapperton, Lander, and Others

- AFRICAN EXPLORERS

- THE EXPLORATION AND COLONIZATION OF AFRICA, II

- VOYAGES ROUND THE WORLD, AND POLAR EXPEDITIONS

- Today's Books

- Today's Pages

- Glimpses of an Unfamiliar Japan, I

- Wanderings in Wessex

- Glimpses of an Unfamiliar Japan, II

- Roving East and Roving West

- The Discovery of the Source of the Nile

- V. CEREMONIES AND FESTIVALS

- Historical Sketch of Naval Architecture

History Moments

October 7, 2013 Leave a Comment

Cartier’s Second Voyage Begins

It was in every way better equipped than that of the preceding year, and consisted of three ships, manned by one hundred ten sailors.

Continuing Cartier Explores Canada , our selection from The History of Canada under French Regime by Henry H. Miles published in 1881. The selection is presented in seven» easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Cartier Explores Canada.

Time: 1535 Place: Canadian Coast

Cartier and his companions were favorably received on their return to France. The expectations of his employers had been to a certain extent realized, while the narrative of the voyage, and the prospects which this afforded of greater results in future, inspired such feelings of hope and confidence that there seems to have been no hesitation in furnishing means for the equipment of another expedition. The Indians who had been brought to France were instructed in the French language, and served also as specimens of the people inhabiting his majesty’s western dominions. During the winter the necessary preparations were made.

On the May 19, 1535, Cartier took his departure from St. Malo on his second expedition. It was in every way better equipped than that of the preceding year, and consisted of three ships, manned by one hundred ten sailors. A number of gentlemen volunteers from France accompanied it. Cartier himself embarked on board the largest vessel, which was named La Grande Hermine, along with his two interpreters. Adverse winds lengthened the voyage, so that seven weeks were occupied in sailing to the Straits of Belle-Isle. Thence the squadron made for the Gulf of St. Lawrence, so named by Cartier in honor of the day upon which he entered it. Emboldened by the information derived from his Indian interpreters, he sailed up the great river, at first named the River of Canada, or of Hochelaga. The mouth of the Saguenay was passed on September 1st, and the island of Orleans reached on the 9th. To this he gave the name “Isle of Bacchus,” on account of the abundance of grape-vines upon it.

On the 16th the ships arrived off the headland since known as Cape Diamond. Near to this, a small river, called by Cartier St. Croix, now the St. Charles, was observed flowing into the St. Lawrence, intercepting, at the confluence, a piece of lowland, which was the site of the Indian village Stadacona. Towering above this, on the left bank of the greater river, was Cape Diamond and the contiguous highland, which in after times became the site of the Upper Town of Quebec. A little way within the mouth of the St. Croix, Cartier selected stations suitable for mooring and laying up his vessels; for he seems, on his arrival at Stadacona, to have already decided upon wintering in the country. This design was favored, not only by the advanced period of the season, but also by the fact that the natives appeared to be friendly and in a position to supply his people abundantly with provisions. Many hundreds came off from the shore in bark canoes, bringing fish, maize, and fruit.

Aided by the two interpreters, the French endeavored at once to establish a friendly intercourse. A chief, Donacona, made an oration, and expressed his desire for amicable relations between his own people and their visitors. Cartier, on his part, tried to allay apprehension, and to obtain information respecting the country higher up the great river. Wishing also to impress upon the minds of the savages a conviction of the French power, he caused several pieces of artillery to be discharged in the presence of the chief and a number of his warriors. Fear and astonishment were occasioned by the sight of the fire and smoke, followed by sounds such as they had never heard before. Presents, consisting of trinkets, small crosses, beads, pieces of glass, and other trifles, were distributed among them.

Cartier allowed himself a rest of only three days at Stadacona, deeming it expedient to proceed at once up the river with an exploring party. For this purpose he manned his smallest ship, the Ermerillon, and two boats, and departed on the 19th of September, leaving the other ships safely moored at the mouth of the St. Charles. He had learned from the Indians that there was another town, called Hochelaga, situated about sixty leagues above. Cartier and his companions, the first European navigators of the St. Lawrence, and the earliest pioneers of civilization and Christianity in those regions, moved very slowly up the river. At the part since called Lake St. Peter the water seemed to become more and more shallow. The Ermerillon, was therefore left as well secured as possible, and the remainder of the passage made in the two boats. Frequent meetings, of a friendly nature, with Indians on the river bank, caused delays, so that they did not arrive at Hochelaga until October 2d.

As described by Cartier himself, this town consisted of about fifty large huts or cabins, which, for purposes of defence, were surrounded by wooden palisades. There were upward of twelve hundred inhabitants,[*] belonging to some Algonquin tribe.

[*] It has not been satisfactorily settled to what tribe the Indians belonged who were found by Cartier at Hochelaga. Some have even doubted the accuracy of his description in relation to their numbers, the character of their habitations, and other circumstances, under the belief that allowance must be made for exaggeration in the accounts of the first European visitors, who were desirous that their adventures should rival those of Cortez and Pizarro. It has also been suggested that the people were not Hurons, but remnants of the Iroquois tribes, who might have lingered there on their way southward. At any rate, when the place was revisited by Frenchmen more than half a century afterward, very few savages were seen in the neighborhood, and these different from those met by Cartier, while the town itself was no longer in existence. Champlain, upward of seventy years after Jacques Cartier, visited Hochelaga, but made no mention in his narrative either of the town or of inhabitants.

More information here and here , and below.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The following year, his ships filled with provisions for a 15-month expedition, Jacques Cartier explored both shores of the St. Lawrence River beginning from Anticosti Island. He was aided in this endeavour by the two Amerindians he had captured during the previous voyage. On September 7, 1535, he dropped anchor on the north side of Île d ...

Cartier's Second Voyage. Cartier returned to make his report of the expedition to King Francis, bringing with him two captured Native Americans from the Gaspé Peninsula. The king sent Cartier ...

Cartier's Second Voyage Jacques Cartier's first voyage was effectively a failure, but upon his return to France on September 5, 1534, he remained optimistic. With Dom Agaya and Taignoagny ...

Jacques Cartier's Second Voyage Gilcrease Museum. The Second Voyage Undertaken by the Command and Wish of the Most Christian King of France, Francis the First of That Name, for the Completion of the Discovery of the Western Lands, Lying under the Same Climate and Parallels as the Territories and Kingdom of That Prince.

Jacques Cartier's second voyage to the New World commenced on May 19, 1535, a little more than a year after his return from his initial expedition. This time, Cartier commanded a flotilla of three ships—the Grande Hermine, the Petite Hermine, and the Émérillon—with a crew totaling around 110 men. His main objective remained the same: to ...

Jacques Cartier (31 December 1491 - 1 September 1557) was a French-Breton maritime explorer for France.Jacques Cartier was the first European to describe and map the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the shores of the Saint Lawrence River, which he named "The Country of Canadas" [citation needed] after the Iroquoian names for the two big settlements he saw at Stadacona (Quebec City) and at ...

Second Voyage Upon returning to France, King Francis was impressed with Cartier's report of what he had seen, so he sent the explorer back the following year, in May, with three ships and 110 men.

Jacques Cartier (born 1491, Saint-Malo, Brittany, France—died September 1, 1557, near Saint-Malo) was a French mariner whose explorations of the Canadian coast and the St. Lawrence River (1534, 1535, 1541-42) laid the basis for later French claims to North America ( see New France ). Cartier also is credited with naming Canada, though he ...

On this day of Our Lady the 25th of March in the year 1538 [1539 n.s.] were baptized three male savages from the parts of Canada, taken in the said country by the worthy man Jacques Cartier, Captain for the King our Liege Lord to discover the said lands. The first was named Charles by the venerable and judicious Dom Charles de Champ-Girault ...

During his first voyage to the New World, in 1534, Jacques Cartier explored the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and made contact with the Iroquois. Thanks to their accounts of a fabulously rich Kingdom of Saguenay, a second voyage was rapidly decided upon. Cartier's second voyage to New France (present-day Canada), in 1535-36, resulted in the discovery of the Saint Lawrence River, the most important ...

Cartier: Account of the second voyage to the St. Lawrence River, 1535-1536, excerpts (PDF) Champlain: Account of a battle with the Iroquois, 1609 Marquette & Joliet: Account of the Mississippi River expedition, 1673, Introduction, Pts. 4 & 8 Maps (zoomable):. 1556: New France (map #1, La Nuova Francia) 1664: Canada (map #9, Le Canada faict par le Sr. de Champlain)

Jacques Cartier's voyages of 1534, 1535, and 1541constitute the first record of European impressions of the St Lawrence region of northeastern North American and its peoples. The Voyages are rich in details about almost every aspect of the region's environment and the people who inhabited it.As Ramsay Cook points out in his introduction, Cartier was more than an explorer; he was also Canada's ...

The Voyages of Jacques Cartier. Jacques Cartier's voyages of 1534, 1535, and 1541constitute the first record of European impressions of the St Lawrence region of northeastern North American and its peoples. The Voyages are rich in details about almost every aspect of the region's environment and the people who inhabited it.

A Shorte and Briefe Narration<br>(Cartier's Second Voyage),<br>1535-1536<br>CONTENTS<br>Introduction 35<br>Cartier again reaches Newfoundland 38<br>Re-enters the Gulf of St. Lawrence 38<br>Explores the Shores of the Gulf on the North and West 39<br>Discovers the St. Lawrence River 41<br>Explores it as far as the Site of Quebec 43<br>Holds Intercourse with the Natives 46<br>Ascends the River in ...

Cartier's Second Voyage, 1535-1536. On May 19, 1535, Jacques Cartier's expedition set out from St. Malo, France, to discover the riches rumored to exist in the three western "kingdoms" of Saguenay, Canada, and Hochelaga. Accompanied by many gentlemen and treasure seekers, Cartier's expedition encountered severe storms and finally ...

The second voyage of Jacques Cartier, undertaken in the years 1535 and 1536, is the exploit on which his title to fame chiefly rests. In this voyage he discovered the river St Lawrence, visited the site of the present city of Quebec, and, ascending the river as far as Hochelaga, was enabled to view from the summit of Mount Royal the imposing panorama of plain and river and mountain which marks ...

Document Number: AJ-027: Author: Cartier, Jacques, 1491-1557: Title: Shorte and Briefe Narration (Cartier's Second Voyage), 1535-1536: Source: Burrage, Henry S. (editor).

Cartier's Second Voyage Begins. It was in every way better equipped than that of the preceding year, and consisted of three ships, manned by one hundred ten sailors. our selection from The History of Canada under French Regime by Henry H. Miles published in 1881. The selection is presented in seven» easy 5 minute installments.

Document 1: Jacques Cartier's Second Voyage to the St. Lawrence River and Interior of "Canada," 1535-1536 . The Second Voyage Undertaken by the Command and Wish of the Most Christian King. of France, Francis the First of That Name, for the Completion of the Discovery of the

FC Saturn Moscow Oblast (Russian: ФК "Сатурн Московская область") was an association football club from Russia founded in 1991 and playing on professional level between 1993 and 2010. Since 2004 it was the farm club of FC Saturn Moscow Oblast. In early 2011, the parent club FC Saturn Moscow Oblast went bankrupt and dropped out of the Russian Premier League due to huge ...

Its a city in the Moscow region. As much effort they take in making nice flags, as low is the effort in naming places. The city was founded because they built factories there.

In 1938, it was granted town status. [citation needed]Administrative and municipal status. Within the framework of administrative divisions, it is incorporated as Elektrostal City Under Oblast Jurisdiction—an administrative unit with the status equal to that of the districts. As a municipal division, Elektrostal City Under Oblast Jurisdiction is incorporated as Elektrostal Urban Okrug.

Elektrostal. Elektrostal ( Russian: Электроста́ль) is a city in Moscow Oblast, Russia. It is 58 kilometers (36 mi) east of Moscow. As of 2010, 155,196 people lived there.