Crocodile encounters in Australia’s Northern Territory

Aug 7, 2018 • 5 min read

A saltwater crocodile cooling himself with his open mouth © Australian Scenics / Getty Images

The closest living relative to the dinosaur, with a bite force thought to rival that of a T.Rex, saltwater crocodiles are the ultimate apex predators. With more than 100,000 of them patrolling the waterways of Australia’s Northern Territory alone – that’s one saltie for every two human residents – it’s the best place on the planet to see these reptilian relics in action.

Valued at more than AU$100 million, the Northern Territory’s crocodile industry isn’t just important to the local economy, but also to croc conservation, with croc tourism – and even croc farming – credited for an enormous rebound in their numbers since they became a protected species in the 1970s. There are now loads of ways to see a crocodile up close in the Top End, from low-impact wildlife viewing to more manufactured interactions. Given claims by animal welfare experts that using animals for the purpose of entertainment can be harmful for them, however, some options raise ethical questions. To help you make the most informed decision about how you spend your croc-viewing dollars in Australia, we take a closer look at the most popular experiences accessible from Darwin.

Whichever way you decide to go croc-spotting, don’t forget to be croc-wise: stay well back from the edge of any waterway where crocs may live, and don’t even think about taking a dip in any Top End water body unless official signage designates it croc-free, even if it doesn’t seem like there are any crocs around.

Corroboree Billabong boat tours

Part of the Mary River Wetlands – home to the world’s largest concentration of saltwater crocs – Corroboree Billabong is one of the best places in the Top End to see crocs in their natural habitat. On a boat cruise along the scenic billabong, 100km east of Darwin, you’ll spot plenty of salties as well as a huge variety of bird species and other wildlife that call the waterlily-rimmed billabong home. Crocs here are not baited, fed or prodded to perform for tourists, ensuring a relaxed, organic wildlife-spotting experience, with an informative commentary provided by knowledgeable guides.

Cahill’s Crossing

Known as Australia’s most dangerous water crossing, this shallow causeway across the East Alligator River in Kakadu National Park sees dozens of crocs congregate to feast on swarms of fish heading upstream when the road is submerged by the incoming tide. Despite its remote location, the spectacle always draws a crowd of tourists who line the west bank with their cameras and fishing rods.

Trying to cross the muddy river at high tide is prohibited, yet each year dozens of brazen drivers attempt it and end up being washed into the croc-infested waters. In 2017 a man was killed by a crocodile while attempting the crossing on foot, while others have been snatched while standing too close to the riverbank. You’ve been warned.

Outback Floatplane Adventures

This adrenaline-packed tour begins with a scenic floatplane ride across Darwin Harbour to the stunningly remote Sweets Lagoon – the former lurking ground of Sweetheart, the enormous stuffed saltie on display at Darwin’s Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory . Otis, a 4.6m saltie, is likely to be hanging around the pontoon to greet you before you head off on a boat cruise along the pristine lagoon, followed by an airboat tour along narrower surrounding waterways crawling with crocs. If you’re lucky, you might also meet some of Otis’ neighbours, who have names like ‘Chug’, ‘Bone Cruncher’ and ‘Nitro’.

While the half-day tour isn’t cheap, it’s one of the Top End’s best thrills, buoyed by the expertise of guides who know the lagoon – and its resident crocs – inside out. There’s no croc feeding, though you’re welcome to tempt Otis by taking a dip in a swimming cage attached to the side of the pontoon.

Crocodylus Park

The brainchild of renowned crocodile biologist Professor Grahame Webb , Crocodylus Park , 15km from the centre of Darwin, is home to more than 1000 crocs (including salties, freshies and American alligators) and a mini-zoo comprising big cats, monkeys, large birds and more. Tours (held four times daily), include informative wildlife talks and croc feeding and handling sessions, with a new boat cruise offering an opportunity to view salties in a more ‘natural’ setting.

Jumping croc boat tours

Perhaps only when you see a saltie launch its enormous body out of the water to snatch its prey can you fully appreciate the extent of its power. On an hour-long jumping croc cruise down the Adelaide River, about 75 minutes drive from Darwin , you can expect to get a good fright or two when locals such as Dominator and his arch rival Brutus, two of the river’s biggest salties, jump out of the murky water to snap up hunks of meat dangled from poles alongside your tour boat.

Jumping croc tours (there are several operators) are regulated to ensure crocs aren’t fed anything they wouldn’t usually eat in the wild, with snacks doled out in small enough portions to prevent crocs becoming dependent on them as their key food source. It’s worth noting, however, that feeding wild animals – including crocodiles – is discouraged by animal welfare experts, as well as the Northern Territory government itself.

Crocasaurus Cove

The closest you can get to swimming with a croc without becoming its next meal, this croc theme park of sorts in central Darwin is best known for its ‘Cage of Death’, a super-strong clear cylinder with room for two people that is lowered into a pool containing a large saltwater crocodile.

Crocosaurus Cove’s larger residents include a former showbiz croc and several ‘problem crocs’ with a taste for boat motors or livestock that typically sees repeat offenders put down, though critics argue this fact doesn’t compensate for the stress the crocs endure while being coaxed by handlers to perform for tourists in the Cage of Death. Baby crocs can also become distressed while being handled, which is another activity on offer here. Other attractions include a reptile display, a freshwater aquarium, a ‘fishing for crocs’ experience and an enclosure of juvenile crocs separated from a swimming pool by a wall of glass.

The writer travelled to the Northern Territory with support from Tourism NT ( northernterritory.com ) and Venture North Safaris ( venturenorth.com.au ). Lonely Planet does not accept freebies for positive coverage.

Explore related stories

Wildlife & Nature

Sep 6, 2024 • 6 min read

Australia has an incredible breadth of unique wildlife but it can be a challenge to locate them. Here's how to respectfully observe the cutest critters.

Aug 8, 2024 • 6 min read

Jun 19, 2024 • 7 min read

May 21, 2024 • 5 min read

Mar 4, 2024 • 8 min read

Nov 5, 2023 • 16 min read

Aug 1, 2023 • 4 min read

Jan 2, 2023 • 12 min read

Nov 24, 2022 • 4 min read

Aug 24, 2022 • 4 min read

- PERPETUAL PLANET

Behind the scenes of a close crocodile encounter

A marine sanctuary teems with life, including a curious crocodile. A photographer has just seconds to decide: intervene or take a picture?

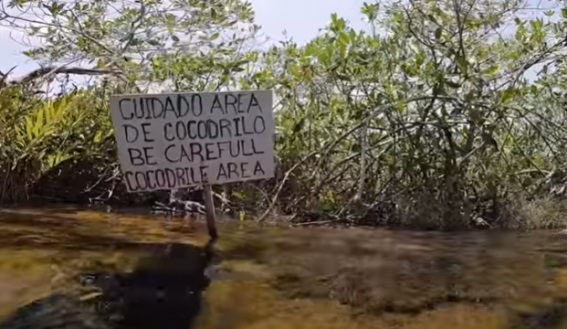

David Doubilet: Gardens of the Queen National Park is a marine sanctuary formed by a necklace of keys, mangrove islets, and reefs about 60 miles south of mainland Cuba. On a previous assignment with my wife and photographic partner, Jennifer Hayes, we’d documented healthy coral reefs pulsing with fish and sharks, and mangroves patrolled by crocodiles. We knew that time, increased tourism, and climate change could alter the 850-square-mile national park—so 15 years later, we returned to see how it was faring.

We were in a mangrove channel photographing Cassiopeia, aka the upside-down jellyfish. Jennifer, her back to me, was focused on a specimen above her. Out of the corner of my viewfinder, I saw a sizable American crocodile drifting downstream. As I began to take its photograph, I realized that the crocodile was going to drift directly between Jennifer and me.

I started to make loud noises through my regulator and moved toward Jen, firing a burst of flash-lit shots to warn her that we had company. She quickly detected my signal and turned to meet our visitor.

Jennifer Hayes: I found myself face-to-snout with an American crocodile . Both surprised and very pleased, I greeted him through my regulator.

DD: She gave me a quick thumbs-up, nodded OK, and burbled an audible “Helloooo, handsome” as she bent closer to take its portrait (shown above). I marveled as she addressed the crocodile with respect, calm curiosity, and absolute joy. She settled in to capture the moment without missing a beat.

JH: I didn’t feel threatened. For several days I’d watched these crocodiles wander about, investigate things in the mangroves, chase fish in circles for fun, and sleep within view of us. Many of them swam with snorkelers on a daily basis. I felt familiar with their behavior—and I had a big SEACAM underwater housing that could double as a mighty shield if needed.

But I want to be clear: I was comfortable with this species of crocodile in this particular place at that particular time. I would not have been comfortable with a more aggressive species, such as a Nile or saltwater crocodile, in a different environment.

DD: When people see the image of the crocodile behind Jennifer, reactions include wonder, awe, and horror. But after a few frames the croc, unimpressed with us, drifted downstream on its way to do other crocodile things. We continued our quest for jellyfish.

JH: Many people ask if I’m angry that David took a picture instead of trying to “save” me. My answer is this: I would have been unhappy if he had not taken the photos. I was a visitor in this creature’s environment, and it was compelled to investigate. This is what I hope for on assignment—I’m not afraid but thrilled to see such an ancient creature.

DD: There is always risk in our line of work. Jennifer and I have aborted many dives with aggressive animals—for our safety and theirs. But this encounter reinforced the good news that we saw all around us in Gardens of the Queen. The crocodile is an indicator species, a symbol of a healthy marine ecosystem that can support apex predators (unlike overfished and degraded areas elsewhere in the Caribbean).

This preserve is a conservation success because it is actively patrolled and protected. The easing of travel restrictions is bound to bring more tourists—so it’s vital to maintain a balance among ecotourism, exploration, and conservation. That’s possible if visitors adopt the same philosophy that we hold toward that curious crocodile and every other marine creature. We enter Earth’s oceans on their terms, not our own.

Related Topics

- UNDERWATER PHOTOGRAPHY

- WILDLIFE PHOTOGRAPHY

- PHOTOGRAPHY

- MARINE SANCTUARIES

- ENVIRONMENT AND CONSERVATION

You May Also Like

7 extraordinary photographers share the stories behind their most iconic images

These images will help you see coral reefs in a whole new way

The Gulf of Maine is warming fast. What does that mean for lobsters—and everything else?

Palau’s waters are some of the most biodiverse in the world—thanks to its defenders

American crocodiles are spreading north in Florida. That’s a good thing.

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- Destination Guide

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Manage Your Subscription

- Give a Gift Subscription

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

- Destinations

- Australia & South Pacific

‘Crocodile Dundee’ Turns 30: How Paul Hogan Changed Tourism in Australia

U.S. audiences were first introduced to Mick “Crocodile” Dundee on Sept. 26, 1986.

Jessica Plautz is the director of content operations at Dotdash Meredith. She previously served as the deputy digital editor of Travel + Leisure . Before joining T+L, Jessica was a travel editor at Mashable .

On Sept. 26, 1986, “Crocodile Dundee” hit theaters in the United States, and Paul Hogan became the face of Australia.

The film, about an Australian bushman who shows a New York journalist the outback before following her back for his first visit to the big city, presented a narrative—and a man—that would define the continent to audiences around the world.

For better or worse—and over the past 30 years it has primarily been for better—the 1986 film is intrinsically linked to the continent.

The story of how it happened, and how Paul Hogan became Australia's representative around the world, is about as fantastic as the film's plot.

The star of “Crocodile Dundee” was no stranger to American television audiences of the 1980s.

He had already made an impact on tourism to Australia, as documented by Jesse Desjardins in a master's thesis on the phenomenon of “Dundee,” in an advertising campaign where he offered to put another “shrimp on the barbie” for visitors to the “wonder down under”:

Hogan spent 10 years working construction before brushing with fame, first making a name for himself with Australian audiences on a show called “New Faces.” On the show, contestants would perform a talent only to be ridiculed by the show's judges. (Simon Cowell had nothing on these guys.)

Hogan had joked with his fellow construction workers about the show, and then in 1971 wrote in to be a contestant saying he was a “ knife-throwing tap dancer .” He got on (because who wouldn't want to see a knife-throwing tap dancer?) and then he spent his time on the show insulting the judges.

The audience ate it up, and “Hoges”' appearances on “New Faces” got him a regular bit on a television news show where he met John Cornell, a journalist-turned-television-producer who became his business partner. After they parlayed his television fame into two wildly successful advertising endorsements—for Winfield cigarettes and Fosters beer, of course—Hogan donated his time to the tourism ads , slowly but surely building an audience in America for his brand of Australia. In retrospect, the pair's strategy looks like it was all done to lead up to “Crocodile Dundee,” which turned Hogan's Australian everyman bit into a blockbuster movie character.

But while Cornell and Hogan had their eyes on the Hollywood prize, as the The New York Times reported in 1988 , they incidentally filmed the best destination advertisement ever created.

The Locations

The iconic images of the “outback” in “Crocodile Dundee” (and “Crocodile Dundee II”) were filmed in Kakadu National Park, the location of a former uranium mine in the Northern Territory outside of Darwin.

“In ’86, Australians hadn't even been to Kakadu, let alone Americans,” Peter Hook, communications manager at Kakadu Tourism, told Travel + Leisure . “Basically Kakadu was a mining area. Uranium was its biggest mineral. The government actually built a road from Darwin to Kakadu—not for tourism, but for mining.”

Today, there are roads to take visitors to those ancient, scenic vistas, but that wasn't the case in 1986. To get a professional film crew to the area was a feat.

The choice of Kakadu for “Crocodile Dundee” came down to a man named Craig Bolles.

“The location was terribly important for the film,” Bolles, who did all the location scouting in Australia, told Kakadu Tourism earlier this year . “It showcased a part of Australia that I don’t think had been seen...and it was inherent in Paul’s nature. He seemed to fit into the landscape perfectly.”

Hogan had grown up in a Sydney suburb, but it was Kakadu that became his cinematic home.

“I had an open brief to choose anywhere in Australia that I thought suitable,” said Bolles, who also considered the northwest region of Kimberley, but ruled it out as too extreme. And Kakadu already posed many challenges for filming.

“Kakadu was a very different place in the 1980s to what it is today,” he said. “Only the main road was sealed (paved) and there were no hotel facilities at all as far as I can remember.”

In fact, it didn't seem there was anywhere for the crew to stay, until Bolles—who spent weeks on making it physically possible for crews and equipment to reach places like Jim Jim Falls and Gunlom Waterfall Creek—happened upon abandoned housing for miners the government had put in.

As anyone who has seen the film knows, the effort paid off.

“Certainly there has been no other place in Australia that has been so well represented and well captured as Hogan did for Kakadu,” Hook told T+L. “It's hard to imagine that anybody could do it as genuinely as he did. ”

The Phenomenon

On a budget of a little more than $7 million, “Crocodile Dundee” brought in more than $300 million at the box office.

Released two years later, “Crocodile Dundee II” repeated that success, bringing in almost $240 million .

Hook says “Crocodile Dundee” couldn't have come out at a better time.

“The timing also was very important, because mid-1980s was when we had a massive wave of American interest in Australia,” he said. “Airfares became a lot more accessible. The Australian dollar was quite low...and, interestingly, that's the scenario now.”

As for why it worked, Tourism Australia's Managing Director John O'Sullivan credits authenticity.

“It's about the genuine nature of the message and the characters within those films,” O'Sullivan told Travel + Leisure .

Tourism Today

Today Chris Hemsworth has taken on being the spokesperson for Australia , but Hogan's legacy is anything but forgotten.

“I think the tourism industry in Australia owes Paul Hogan a hell of a lot of gratitude,” said O'Sullivan.

In the past decade, local tourism offices and businesses all around Australia have joined together in an unprecedented effort to promote tourism to not just Sydney or Melbourne, but to all around Australia.

“One of the big challenges we're really seeking to address is certainly opening up more parts of the country,” said O'Sullivan. “A lot of people think that if you've come to Australia and you've done Sydney Harbor and the Great Barrier Reef, that's it.”

And though Tourism Australia and its many local counterparts are looking to the future, they can also look back for how to inspire travelers.

“In [the first 45 minutes of the film], you see the incredible billabongs...you see the landscapes, which people can see just as Hogan did in the film,” Hook, at Kakadu Tourism, told T+L.

“You look down, and you could be just like Paul Hogan, as if you're the only person in Kakadu. The sense of that you are seeing something special, and quite exclusive, I think that is still very much true to today,” he said. “You can go somewhere and be the only person in your own private rock pool.”

But there's more to it than landscapes, and as Mick Dundee emphasizes in the films, respect for the land and the people is integral to the country.

“The indigenous people of Kakadu go back 50,000 years, and you can get to sites in Kakadu where you can see the story unfolding in front of your eyes: the representations in art over 50,000 years,” said Hook. “I think that's the lesson for anyone who wants to come to Kakadu. Don't look at it like a theme park.”

There have been other films that have featured Australia's amazing landscapes, but according to many observers, “Crocodile Dundee” was unique.

“For me what that film and what he did [was bring] to life that we're a country of friendly and welcoming people,” said O'Sullivan. “[Hogan] certainly introduced the indigenous Australian culture into the U.S.”

“The difference with ‘Crocodile Dundee’ is the actual narrative of the film, this man outside his comfort zone, really resonated,” said Hook. “There was a depth to the film that's made it last.”

Related Articles

Meet Panchito, the croc who swims with tourists in a Tulum cenote.

Through an Instagram video, you can see a crocodile swimming very close to some tourists in the crystal clear waters of a cenote in Tulum.

TULUM QUINTANA ROO (Social Media) – The crocodile’s name is “Panchito.” He is of the Moreletii species, also known as “Mexican crocodile” and he is the inhabitant of the Cenote Manatí or Casa Cenote.

In the video -which has reached 490 thousand reproductions and 8 thousand 195 commentaries- youcan see Panchito peacefully swiming near the tourists.

Ver esta publicación en Instagram Una publicación compartida de sebitastrip ?♂️ (@sebitastrip)

Some users talked about the anxiety they felt seeing Panchito so close to the tourists, while others joked that the crocodile was a vegetarian. But the animal’s passivity, it is said, is because this species is considered harmless; moreover, they claim that he is used to human company.

Who is Panchito? In the video shared by the youtuber and tiktoker Sebitas Trip , you can observe Panchito swimming among the tourists without attacking them. This is because the crocodile came to the waters of the Cenote Manatí five years ago searching for fish. Since then, it has become common to see him in this place.

Photo: Tiktok

Panchito is a swamp crocodile that is characterized by being very territorial. Its diet is based on small mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish, so, according to Sebitas Trip, humans are not seen as food. The only scenarios in which this species would attack a person are if they invade their territory or if their offspring are nearby. But Panchito is already used to the human presence.

The Manatee Cenote The Manatee Cenote is located on Federal Highway 307 on one side of the residential area Tankha, in Riviera Maya, in Quintana Roo, between Puerto Aventuras and Tulum.

https://www.facebook.com/CenoteManati/photos/a.241406062638841/1294474150665355

According to the site’s Facebook page, this cenote received that name because it was home to many manatees. Here you can find crystalline waters with different plays of light due to the natural illumination.

It has a depth of six meters, and you can see in its surroundings mangroves, coral reefs, rock formations, and cracks in the limestone. In the Cenote Manatí, you can also find a cave that flows into the sea.

https://www.facebook.com/CenoteManati/photos/750764618369647

If you decide to go to this cenote in the future, don’t forget the importance of respecting the Riviera Maya’s animal species, such as the Panchito crocodile.

Yucatan Times

Boat adrift in the alacranes reef rescued by state authorities and navy, psychoactive substance found in ancient mayan receptacles.

You may also like

Full internet coverage in all public schools in yucatan is a reality, us seizes venezuela president nicolas maduro’s airplane in the dominican republic, driver hospitalized after accident on the merida progreso, bicyclist found dead on the side of the road in san ignacio, centenario train: 69 years of journeys and history in mérida, the new congress of the state of yucatan takes office, our company.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consect etur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis.

- 01 Central Park, US, New York City

- Phone: (012) 345 6789

- Email: [email protected]

- Support: [email protected]

About Links

- Advertise With Us

- Media Relations

- Corporate Information

- Apps & Products

Useful Links

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Closed Captioning Policy

- Accessibility Statement

- Personal Information

- Data Tracking

- Register New Account

This website uses cookies to improve your experience. We'll assume you're ok with this, but you can opt-out if you wish. Accept

This website uses modern construction techniques, which may not render correctly in your old browser. We recommend updating your browser for the best online experience.

Visit browsehappy.com to help you select an upgrade.

- How Paul Hogan Changed Tourism in Australia

On Sept. 26, 1986, “Crocodile Dundee” hit theaters in the United States, and Paul Hogan became the face of Australia. To celebrate the 30th anniversary of the screening of Crocodile Dundee in the USA, Jessica Plautz, a reporter for America’s most famous travel magazine, Travel + Leisure, looked back at the film and its impact on the way the rest of the world saw Australia.

by Jessica Plautz September 26, 2016 Full story can be viewed at: http://www.travelandleisure.com/culture-design/tv-movies/crocodile-dundee-australia-tourism

The film, about an Australian bushman who shows a New York journalist the outback before following her back for his first visit to the big city, presented a narrative—and a man—that would define the continent to audiences around the world.

For better or worse—and over the past 30 years it has primarily been for better—the 1986 film is intrinsically linked to the continent.

by Jessica Plautz, Travel + Leisure (USA) September 26, 2016 The story of how it happened, and how Paul Hogan became Australia’s representative around the world, is about as fantastic as the film’s plot.

“Hoges” The star of “Crocodile Dundee” was no stranger to American television audiences of the 1980s.

He had already made an impact on tourism to Australia, as documented by Jesse Desjardins in a master’s thesis on the phenomenon of “Dundee,” in an advertising campaign where he offered to put another “shrimp on the barbie” for visitors to the “wonder down under”:

Hogan spent 10 years working construction before brushing with fame, first making a name for himself with Australian audiences on a show called “New Faces.” On the show, contestants would perform a talent only to be ridiculed by the show’s judges. (Simon Cowell had nothing on these guys.)

Hogan had joked with his fellow construction workers about the show, and then in 1971 wrote in to be a contestant saying he was a “knife-throwing tap dancer.” He got on (because who wouldn’t want to see a knife-throwing tap dancer?) and then he spent his time on the show insulting the judges.

The audience ate it up, and “Hoges”’ appearances on “New Faces” got him a regular bit on a television news show where he met John Cornell, a journalist-turned-television-producer who became his business partner. After they parlayed his television fame into two wildly successful advertising endorsements—for Winfield cigarettes and Fosters beer, of course—Hogan donated his time to the tourism ads, slowly but surely building an audience in America for his brand of Australia. In retrospect, the pair’s strategy looks like it was all done to lead up to “Crocodile Dundee,” which turned Hogan’s Australian everyman bit into a blockbuster movie character.

But while Cornell and Hogan had their eyes on the Hollywood prize, as the The New York Times reported in 1988, they incidentally filmed the best destination advertisement ever created.

The Locations The iconic images of the “outback” in “Crocodile Dundee” (and “Crocodile Dundee II”) were filmed in Kakadu National Park, the location of a former uranium mine in the Northern Territory outside of Darwin.

“In ’86, Australians hadn’t even been to Kakadu, let alone Americans,” Peter Hook, communications manager at Kakadu Tourism, told Travel + Leisure.

“Basically Kakadu was a mining area. Uranium was its biggest mineral. The government actually built a road from Darwin to Kakadu—not for tourism, but for mining.”

Today, there are roads to take visitors to those ancient, scenic vistas, but that wasn’t the case in 1986. To get a professional film crew to the area was a feat.

The choice of Kakadu for “Crocodile Dundee” came down to a man named Craig Bolles.

“The location was terribly important for the film,” Bolles, who did all the location scouting in Australia, told Kakadu Tourism earlier this year. “It showcased a part of Australia that I don’t think had been seen…and it was inherent in Paul’s nature. He seemed to fit into the landscape perfectly.”

Hogan had grown up in a Sydney suburb, but it was Kakadu that became his cinematic home.

“I had an open brief to choose anywhere in Australia that I thought suitable,” said Bolles, who also considered the northwest region of Kimberley, but ruled it out as too extreme. And Kakadu already posed many challenges for filming.

“Kakadu was a very different place in the 1980s to what it is today,” he said. “Only the main road was sealed (paved) and there were no hotel facilities at all as far as I can remember.”

In fact, it didn’t seem there was anywhere for the crew to stay, until Bolles—who spent weeks on making it physically possible for crews and equipment to reach places like Jim Jim Falls and Gunlom Waterfall Creek—happened upon abandoned housing for miners the government had put in.

As anyone who has seen the film knows, the effort paid off.

“Certainly there has been no other place in Australia that has been so well represented and well captured as Hogan did for Kakadu,” Hook told T+L. “It’s hard to imagine that anybody could do it as genuinely as he did. ”

The Phenomenon On a budget of a little more than $7 million, “Crocodile Dundee” brought in more than $300 million at the box office.

Released two years later, “Crocodile Dundee II” repeated that success, bringing in almost $240 million.

Hook says “Crocodile Dundee” couldn’t have come out at a better time.

“The timing also was very important, because mid-1980s was when we had a massive wave of American interest in Australia,” he said. “Airfares became a lot more accessible. The Australian dollar was quite low…and, interestingly, that’s the scenario now.”

As for why it worked, Tourism Australia’s Managing Director John O’Sullivan credits authenticity.

“It’s about the genuine nature of the message and the characters within those films,” O’Sullivan told Travel + Leisure.

Tourism Today Today Chris Hemsworth has taken on being the spokesperson for Australia, but Hogan’s legacy is anything but forgotten.

“I think the tourism industry in Australia owes Paul Hogan a hell of a lot of gratitude,” said O’Sullivan.

In the past decade, local tourism offices and businesses all around Australia have joined together in an unprecedented effort to promote tourism to not just Sydney or Melbourne, but to all around Australia.

“One of the big challenges we’re really seeking to address is certainly opening up more parts of the country,” said O’Sullivan. “A lot of people think that if you’ve come to Australia and you’ve done Sydney Harbor and the Great Barrier Reef, that’s it.”

And though Tourism Australia and its many local counterparts are looking to the future, they can also look back for how to inspire travelers.

“In [the first 45 minutes of the film], you see the incredible billabongs…you see the landscapes, which people can see just as Hogan did in the film,” Hook, at Kakadu Tourism, told T+L.

“You look down, and you could be just like Paul Hogan, as if you’re the only person in Kakadu. The sense of that you are seeing something special, and quite exclusive, I think that is still very much true to today,” he said. “You can go somewhere and be the only person in your own private rock pool.”

“The indigenous people of Kakadu go back 50,000 years, and you can get to sites in Kakadu where you can see the story unfolding in front of your eyes: the representations in art over 50,000 years,” said Hook. “I think that’s the lesson for anyone who wants to come to Kakadu. Don’t look at it like a theme park.”

The Legacy There have been other films that have featured Australia’s amazing landscapes, but according to many observers, “Crocodile Dundee” was unique.

“For me what that film and what he did [was bring] to life that we’re a country of friendly and welcoming people,” said O’Sullivan. “[Hogan] certainly introduced the indigenous Australian culture into the U.S.”

“The difference with ‘Crocodile Dundee’ is the actual narrative of the film, this man outside his comfort zone, really resonated,” said Hook. “There was a depth to the film that’s made it last.”

http://www.travelandleisure.com/culture-design/tv-movies/crocodile-dundee-australia-tourism

- FB icon Follow us on Facebook

- insta icon Follow us on Instagram

The annual @million_dollar_fish competition is back from 01 October giving fisho's the chance to win $1 million! Registrations are now open so head over to their website so you're in for a chance to win: milliondollarfish.com.au Will we more lucky winners at Kakadu? 🤞🏼 #milliondollarfish #fishos #fishingtips #dokakadu

📷 Get your camera ready! A new tour "Lightning Dreaming Tour" has been announced by Northern Territory wildlife and landscape photographer Paul Thomsen. A once in a lifetime Northern Territory Wet Season Experience, this 7 night tour will see guests spend 5 nights in Kakadu and 2 nights at the Finniss River Lodge where you'll enjoy incredible natural landscape and wildlife photography in the wild Top End, for all levels of experience. 📸 Includes: workshops and special access to amazing photography locations. 📸 Dates: December 4-11th from Darwin and numbers are limited. 📸 Leading NT photographers Paul Thomsen (Wildfoto) and Etienne Littlefair (Wild Territory Images) will be your guides! To find out more or to secure your spot, visit: wildfoto.au/lightningdreamingtour #wildlifephotography #topend #topendnt #naturephotography #photographytour

📣 Just dropped - the Outback Retreat at @cooindalodgekakadu is now just $249* per night! 🤩 Built on an elevated platform to ensure year-round usability and minimal environmental impact Cooinda's Outback Retreat safari tents offer an enchanting escape into the Australian wilderness, perfect for a couple getaway or a family adventure! Their harmonious blend of comfort and nature make these canvas sanctuaries redefine the notion of camping; each interior meticulously designed to reflect the unique landscape of Kakadu with an array of locally designed elements. Our Outback Retreats feature their own luxurious shared bathroom and amenities block, which include laundry facilities and a small kitchenette, ensuring a delightful and convenient stay for our guests. And if you’re travelling with the kids, book the Outback Retreat Family with bunk beds, separated by a dividing wall. Be quick, this special offer is available now for stays until 13 October, 2024. Book online at: kakadutourism.com or see link in bio 👆🏼 * Subject to availability. Must be pre-paid and is non-refundable. Book and travel by 13 October, 2024.

🐦 Kakadu Bird Week | 26 - 29 September Bird Week is a spectacular event that coincides with the dramatic mass migration of magpie geese. These magnificent birds flock to the billabongs, like Yellow Water (Ngurrungurrudjba), to feed, creating a breathtaking spectacle as the waters recede towards the end of the dry season. This is the perfect time to witness not only the diverse birdlife but also Kakadu’s impressive array of exotic wildlife, including crocodiles, buffalo, brumbies, and wallabies. Join our local NT Bird Specialist, Luke Paterson, during select morning and afternoon cruises during Kakadu Bird Week where Luke will focus on the bird life in the area whilst sharing his expertise on many of the 280+ bird species in the area. Don’t forget your binoculars and zoom lens! Book your Bird Week cruise now: https://app.respax.com/public/kt/tourinformation/BRDWK #birdweek #kakadubirdweek #ntaustralia #lukepaterson #yellowwatercruise #booknow #twitcher #birdlover #naturelover

Did you know that Parks Australia offers a range of Bininj/Mungguy led FREE activities from 29 May to 4 October 2024. It is a great opportunity to connect with our Bininj/Mungguy (Aboriginal) Country and Culture as Bininj/Mungguy guide you through some of Kakadu’s stunning sites. The activities include: 👉🏼 Nawurlandja sunset walk 👉🏼 Anbangbang billabong walk 👉🏼 Kungardun bush walk 👉🏼 Ubirr Rock Art and Sunset Experience 👉🏼 Cahills Crossing Croc Talk Bookings are handled through Eventbrite. Group sizes are limited and you will need to bring your park pass, visitor guide and arrive at your activity site 10 minutes early. For more information on seasonal guided activities, please call the Bowali Visitor Centre on 08 8938 1120. Images from @seekakadu [IG] #kakadutours #rangertours #parkranger #dokakadu

Visit Kakadu

- About Kakadu

- Where to Stay

- See & Do

- Build My Itinerary

- Media & Blog

Stay Connected

Exclusive specials and announcements!

© Copyright 2023 - 2024 Kakadu Tourism

- Terms & Conditions

site by Karmabunny

Winter is here! Check out the winter wonderlands at these 5 amazing winter destinations in Montana

- Travel Destinations

- Australia & South Pacific

It’s Always Croc Season In Darwin And The Top End

Published: September 7, 2023

Modified: December 27, 2023

by Jeri Samson

- Safety & Insurance

- Travel Tips

Introduction

Welcome to the land down under, where the land itself is as wild as the creatures that inhabit it. Australia, known for its diverse wildlife, boasts some of the most unique and fascinating animals on the planet. And when it comes to dangerous predators, few can rival the fearsome reputation of the crocodile.

Nowhere is this more evident than in Darwin and the Top End of Australia. Here, crocodiles are not just a tourist attraction, but a way of life. The region is home to a large population of saltwater crocodiles, often referred to as “salties” by the locals. These apex predators dominate the waterways, effortlessly gliding through the murky depths and lurking in the shadows, waiting for an opportune moment to strike.

Visitors to Darwin and the Top End are in for a unique and thrilling experience, as they navigate the delicate balance between human activities and the natural habitat of these prehistoric creatures. From crocodile cruises and wildlife parks to adrenaline-pumping crocodile encounters, there are plenty of opportunities to get up close and personal with these ancient reptiles.

But before delving into the world of crocodiles in Darwin and the Top End, it’s important to understand their habitats, the different species found in the region, conservation efforts, safety tips for visitors, popular crocodile spotting locations, the emergence of crocodile tourism, and the stark realities of crocodile attacks.

So fasten your seatbelts and prepare for an adventure like no other. It’s time to dive into the world of crocodiles in Darwin and the Top End, where it’s always croc season.

Crocodiles in Darwin and the Top End

Darwin and the Top End region of Australia are known for their thriving population of crocodiles. These magnificent creatures have been roaming the waterways for millions of years, adapting and evolving in response to the ever-changing environment.

One of the primary reasons for the prevalence of crocodiles in this region is the presence of suitable habitats. The lush mangrove forests, expansive wetlands, and meandering river systems provide the ideal conditions for these reptiles to thrive. The warm climate and abundant food sources further contribute to their numbers.

The Top End is home to two species of crocodiles: the saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) and the freshwater crocodile (Crocodylus johnstoni). The saltwater crocodile, also known as the estuarine crocodile, is the largest living reptile on Earth and can grow up to 6 meters in length. They are well-known for their powerful jaws, incredible strength, and ability to ambush their prey.

On the other hand, the freshwater crocodile is smaller in size, typically reaching lengths of around 3 meters. They are more timid and less aggressive compared to their saltwater counterparts. Freshwater crocodiles are commonly found in rivers, billabongs, and inland water systems, away from the brackish and saltwater environments preferred by saltwater crocodiles.

Despite their fearsome reputation, crocodiles in Darwin and the Top End play a vital role in the ecosystem. They are apex predators and help maintain the balance of the local food chain. By regulating the population of prey species, they ensure the overall health and sustainability of the region’s biodiversity.

As a result, there are ongoing efforts to conserve and protect crocodile populations in the area. Various management strategies are in place to minimize human-crocodile encounters and promote coexistence between humans and these ancient reptiles. These efforts include educational campaigns, crocodile tagging programs, and the establishment of designated crocodile habitats.

Understanding the behavior, habitats, and ecological importance of crocodiles in Darwin and the Top End is essential for both residents and visitors. By respecting their natural environment and following safety guidelines, we can appreciate and enjoy the presence of these magnificent creatures while minimizing the risks associated with their presence.

Crocodile Habitats

Crocodiles are incredibly adaptable creatures, capable of surviving in a wide range of habitats. In Darwin and the Top End region of Australia, these reptiles have established their territories in diverse environments, each offering unique advantages for their survival.

The primary habitats for crocodiles in this region are the mangrove forests, wetlands, and river systems. Mangroves provide an ideal setting for these reptiles, offering shelter, warmth, and abundant food sources. The dense network of roots and branches creates a labyrinth of hiding spots, allowing crocodiles to sneak up on their prey and ambush them with remarkable precision.

Wetlands, including billabongs, swamps, and floodplains, are another crucial habitat for crocodiles in Darwin and the Top End. These expansive areas offer shallow waters and plenty of vegetation, attracting a variety of animals, both terrestrial and aquatic. Crocodiles thrive in these wetlands, utilizing the cover of vegetation to hide and patiently wait for an opportunity to strike.

Additionally, river systems are a major crocodile habitat in the region. With their deep channels and extensive networks, rivers provide an excellent platform for crocodiles to hunt and move around. The mix of freshwater and saltwater environments along these rivers supports both freshwater and saltwater crocodile populations, each adapted to their preferred water conditions.

While saltwater crocodiles are often associated with coastal regions, they are also found in inland water systems, including rivers, estuaries, and even sometimes in freshwater billabongs. Freshwater crocodiles, on the other hand, primarily inhabit freshwater bodies such as rivers, billabongs, and smaller waterways.

It’s worth noting that crocodiles are territorial creatures, with each individual staking out its own area. They fiercely defend their territories from other crocodiles, making habitat availability a crucial factor in determining their population density in certain areas.

Understanding the diverse habitats of crocodiles in Darwin and the Top End is essential for both researchers and tourists. It allows us to appreciate the adaptability of these ancient reptiles and the significance of preserving their habitats for the overall health of the local ecosystem.

Crocodile Species Found in the Region

Darwin and the Top End of Australia are home to two distinct species of crocodiles: the saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) and the freshwater crocodile (Crocodylus johnstoni). While both species share some similarities, they have distinct characteristics and ecological preferences.

The saltwater crocodile, also known as the estuarine crocodile, is the largest living reptile on Earth. Males can grow up to 6 meters in length, and females typically reach about 3-4 meters. They have a robust build, powerful jaws, and a reputation for being formidable apex predators.

Saltwater crocodiles are well-adapted to both saltwater and brackish environments, such as estuaries, coastal mangroves, and freshwater river systems. They have a remarkable ability to regulate their salt levels, allowing them to venture into various habitats. This adaptability has contributed to their widespread distribution across the Top End region.

In contrast, freshwater crocodiles are smaller in size, usually growing up to 3 meters in length. They have a more slender build and a longer, narrower snout compared to saltwater crocodiles. This species predominantly inhabits freshwater ecosystems, including rivers, billabongs, and inland waterways away from the coastal areas.

Freshwater crocodiles have a less aggressive nature and are more tolerant of human presence. They primarily feed on fish, crustaceans, and small reptiles, and they are known for their ability to bask in the sun, often seen perched on rocks or logs near the water’s edge.

Both saltwater and freshwater crocodiles are integral parts of the ecosystem in Darwin and the Top End. They play a crucial role in regulating prey populations, keeping a balance in the food chain, and contributing to the overall health of the region’s diverse habitats.

It’s important to note that while these crocodile species are fascinating to observe, precautions should be taken to ensure human safety and minimize any negative interactions. Understanding the characteristics and behavior of each species can help visitors make informed decisions and appreciate these impressive creatures from a safe distance.

Crocodile Conservation Efforts

Recognizing the importance of maintaining a healthy balance between humans and crocodiles, various conservation efforts have been implemented in Darwin and the Top End to protect these majestic creatures and their habitats. These initiatives aim to ensure the long-term survival of crocodile populations while minimizing the risks associated with human interactions.

One of the key strategies in crocodile conservation is education and awareness. Local authorities, wildlife organizations, and tour operators work together to educate residents and visitors about crocodile behavior, safety guidelines, and the importance of respecting crocodile habitats. This includes providing informational materials, conducting workshops, and promoting responsible tourism practices.

Crocodile research and monitoring programs are also vital for conservation efforts. Scientists and researchers study crocodile populations, behavior, and movements to gain insights into their ecological needs and behavior patterns. This information helps in the development of targeted management plans and the identification of critical habitat areas that require protection.

Crocodile tagging programs play a crucial role in monitoring crocodile populations. By tagging individuals with radio transmitters or GPS trackers, researchers can track their movements, study their interactions with their environment, and monitor population trends. This data helps inform effective management decisions and enables a better understanding of crocodile behaviors.

Designating protected areas and implementing specific management plans for these areas is another cornerstone of crocodile conservation. Establishing crocodile sanctuaries and protected habitats ensures that these reptiles have undisturbed areas to nest, breed, and thrive. These protected zones form important refuges where crocodile populations can grow and flourish without human interference.

Additionally, crocodile egg collection and relocation programs have been implemented to help mitigate potential conflicts between humans and crocodiles. These programs involve the relocation of crocodile nests from high-risk areas to designated hatcheries, where the eggs can safely hatch and the young crocodiles can be released into suitable habitats away from populated areas.

Conservation efforts also extend to local communities, as their cooperation and participation are fundamental to the success of crocodile conservation. Encouraging responsible behavior around crocodile habitats, such as avoiding swimming in crocodile-inhabited waters, not feeding crocodiles, and reporting any potential threats or sightings, is essential in maintaining a safe coexistence between humans and crocodiles.

By implementing these conservation measures, Darwin and the Top End strive to ensure that crocodiles remain a vital part of the region’s unique ecosystem, while safeguarding the well-being of both humans and these ancient reptiles.

Crocodile Safety Tips for Visitors

Visiting Darwin and the Top End of Australia offers an exciting opportunity to witness crocodiles in their natural habitat. However, it’s crucial to prioritize safety and understanding to prevent any potential conflicts or dangerous encounters with these powerful reptiles. Here are some essential crocodile safety tips for visitors:

- Stay informed: Educate yourself about crocodile behavior and habitats before your visit. Understand the local regulations and guidelines regarding crocodile interactions and follow them strictly.

- Observe from a safe distance: Keep a safe distance from crocodiles at all times. Use binoculars or zoom lenses to observe them without approaching too closely.

- Stick to designated areas: Stay within designated viewing platforms or areas that are considered safe for crocodile spotting. Do not venture into unmarked or unauthorized areas where crocodiles may be present.

- Do not feed crocodiles: Feeding crocodiles is not only dangerous but also detrimental to their natural behavior. Feeding can encourage aggressive behavior and create dependency on humans as a food source.

- Avoid swimming in crocodile-inhabited waters: Always swim in designated safe swimming areas and heed any warning signs indicating the presence of crocodiles. Never swim in rivers, estuaries, or billabongs where crocodiles may be present.

- Be cautious near the water’s edge: Keep a safe distance from the water’s edge, especially in areas known to have crocodiles. Remember that crocodiles can lunge out of the water with incredible speed, so remain vigilant at all times.

- Travel in groups: When exploring crocodile habitats, travel in groups rather than alone. This increases safety and ensures there are multiple sets of eyes watching for any potential crocodile activity.

- Do not provoke or harass crocodiles: Avoid any actions that may agitate or provoke a crocodile, such as loud noises, splashing, or throwing objects towards them. Respect their habitat and maintain a quiet and calm demeanor.

- Follow the advice of local guides: If participating in a crocodile-focused activity or tour, listen carefully to the instructions and guidance provided by experienced guides. They have extensive knowledge of crocodile behavior and can ensure your safety during the encounter.

- Report any crocodile sightings or concerns: If you come across a crocodile or suspect any potential risks, report it to the appropriate authorities or park rangers. They can assess the situation and take necessary actions to ensure public safety.

By following these crocodile safety tips, visitors can enjoy their time in Darwin and the Top End while minimizing the risks associated with wild crocodile encounters. Remember, respect for these powerful reptiles and their natural habitats is key to a safe and memorable experience.

Popular Crocodile Spotting Locations

Darwin and the Top End of Australia offer numerous opportunities for visitors to witness crocodiles in their natural habitats. From dedicated wildlife parks to scenic waterways, here are some popular crocodile spotting locations that provide unforgettable encounters with these ancient reptiles:

- Adelaide River: Located just south of Darwin, the Adelaide River is renowned for its abundance of saltwater crocodiles. Many tour operators offer crocodile cruises along the river, providing a safe and thrilling experience to observe these impressive creatures up close.

- Kakadu National Park: This UNESCO World Heritage Site is not only famous for its stunning landscapes and rich cultural history but also for its diverse wildlife, including crocodiles. Boat tours along waterways like the Yellow Water Billabong offer a chance to spot crocodiles basking in the sun or stealthily patrolling the waters.

- Mary River Region: The Mary River region, located east of Darwin, is home to one of the highest densities of saltwater crocodiles in Australia. The wetlands and river systems in this area offer excellent crocodile spotting opportunities, especially during the breeding season.

- Crocodylus Park: Situated just outside Darwin, Crocodylus Park is a must-visit for crocodile enthusiasts. The park houses a large collection of crocodiles, providing visitors with a chance to see these incredible creatures up-close and learn about their behaviors and conservation efforts.

- Corroboree Billabong: Located about 90 minutes from Darwin, Corroboree Billabong is a picturesque wetland renowned for its crocodile population. Boat tours take visitors through the billabong, allowing them to observe crocodiles and other wetland wildlife in their natural habitat.

- Mary River National Park: This expansive national park is known for its diverse wildlife, including its resident saltwater crocodile population. Visitors can take guided cruises or explore walking trails to catch glimpses of these impressive creatures in their native environment.

- Window on the Wetlands: Offering panoramic views of the wetlands surrounding the Adelaide River, the Window on the Wetlands Visitor Centre provides an opportunity to learn about the diverse ecosystems and spot crocodiles in action. Interpretive displays and viewing platforms offer great vantage points for observing these ancient reptiles.

- Litchfield National Park: While Litchfield National Park is most famous for its waterfalls and stunning landscapes, it’s also home to freshwater crocodiles. Visitors can safely observe these crocodiles in swimming areas such as Wangi Falls or at the banks of the Tiwi Art Site walk.

It’s important to note that crocodile spotting should be done with caution and respect for the safety guidelines in place. It’s always advisable to join organized tours or visit designated crocodile viewing areas where experienced guides can provide insightful information and ensure a safe experience for all.

So, get ready for an unforgettable adventure as you explore these popular crocodile spotting locations in Darwin and the Top End, immersing yourself in the wonders of the natural world and witnessing the power and beauty of these incredible reptiles.

Crocodile Tourism in Darwin and the Top End

When it comes to tourism in Darwin and the Top End, crocodiles play a significant role in attracting visitors from around the world. The region’s unique ecosystem, rich biodiversity, and the allure of witnessing these prehistoric creatures in their natural habitat make crocodile tourism a thriving industry.

Crocodile tours and cruises are one of the most popular ways for visitors to experience these ancient reptiles up close. Knowledgeable guides provide insights into crocodile behavior, habitats, and conservation efforts as they navigate the waterways. These tours offer a safe and exhilarating opportunity to observe crocodiles in their natural environment.

Furthermore, some wildlife parks and sanctuaries in the region provide educational programs and interactive experiences centered around crocodiles. Visitors can learn about crocodile conservation, witness feeding demonstrations, and even cuddle baby crocodiles under the supervision of experienced handlers.

For those seeking a more adventurous experience, cage diving or swimming with crocodiles is an option. With the utmost precaution and under the guidance of trained professionals, participants can get a close-up view of these fascinating creatures while inside a submerged cage.

Crocodile-themed events and festivals are also popular in Darwin and the Top End. The famous Crocodile Dundee Festival celebrates Australia’s crocodile heritage with a range of entertainment, including crocodile-themed competitions and showcases of local arts, crafts, and cuisine. These events offer a unique and immersive experience, blending entertainment with educational opportunities.

It’s important to note that while crocodile tourism is a thriving industry, responsible and sustainable practices are crucial in order to protect the welfare of both the crocodiles and the environment. Tour operators and wildlife parks adhere to strict regulations to minimize the impact of tourism activities on natural habitats and ensure the safety of both visitors and crocodiles.

By participating in crocodile tourism activities, visitors not only have the chance to witness one of nature’s most captivating creatures, but they also contribute to the local economy and support conservation efforts. Revenue generated from tourism often goes towards funding research, conservation programs, and initiatives aimed at preserving crocodile populations and their habitats.

Crocodile tourism in Darwin and the Top End invites visitors to immerse themselves in the natural wonders of the region, offering a unique opportunity to connect with these ancient reptiles and gain a deeper appreciation for their role in the ecosystem.

Crocodile Attacks: Facts and Statistics

Crocodile attacks, while relatively rare, are a sobering reminder of the inherent risks associated with being in close proximity to these powerful creatures. Understanding the facts and statistics surrounding crocodile attacks in Darwin and the Top End can help visitors make informed decisions and prioritize their safety when exploring crocodile-infested habitats.

It’s important to note that most crocodile attacks occur when humans unintentionally enter crocodile habitats or engage in high-risk behaviors. Here are some key facts and statistics regarding crocodile attacks:

- Species involved: Saltwater crocodiles are responsible for the majority of crocodile attacks on humans. Their immense size, strength, and aggressive nature make them potentially dangerous predators.

- Preventable incidents: Many crocodile attacks can be prevented by exercising caution and following safety guidelines. Engaging in activities such as swimming in crocodile-inhabited waters or approaching crocodiles in their natural habitat significantly increases the risk of an attack.

- Attack frequency: While specific statistics vary, crocodile attacks in Darwin and the Top End are relatively rare. The Australian government has implemented stringent measures to minimize the risks and ensure public safety in crocodile-prone areas.

- Tourist encounter safety: Crocodile tourism operators prioritize visitor safety and abide by strict regulations to ensure minimal risks during guided tours and cruises. Visitors should choose reputable operators and follow their instructions at all times.

- Recorded attacks: Despite precautions, occasional crocodile attacks do occur. It’s crucial to report any sighting or potential threat promptly to local authorities or park rangers to mitigate risks and prevent further incidents.

- Survival rates: The outcome of a crocodile attack can vary, depending on the circumstances and the response of the victim. Survival rates are influenced by factors such as the size of the crocodile, the severity of the attack, and the promptness of medical assistance.

- Shared responsibility: Crocodile safety is a shared responsibility between authorities, tourism operators, and individuals. Ongoing efforts in crocodile conservation and safety awareness help minimize risks and promote safe coexistence between humans and crocodiles.

While it’s important to be aware of the risks associated with crocodile encounters, it’s essential to approach these creatures with respect and caution. By adhering to safety guidelines, staying informed, and utilizing the services of reputable operators, visitors can enjoy the beauty and wonder of Darwin and the Top End while ensuring their own safety and the protection of these incredible reptiles.

Darwin and the Top End of Australia provide a remarkable opportunity to explore the world of the ancient and formidable crocodiles. These reptiles, known for their size, strength, and primal nature, inhabit the diverse habitats of the region, making crocodile encounters a thrilling and immersive experience.

From the murky waters of the Adelaide River to the expansive wetlands of Kakadu National Park, crocodile enthusiasts have a range of popular spots to witness these creatures in their natural environment. Tour operators, wildlife parks, and educational programs offer opportunities to observe and learn about these ancient reptiles while promoting responsible and safe practices.

Crocodile conservation efforts in Darwin and the Top End are essential for the long-term survival of both crocodile populations and the delicate ecosystems they inhabit. Through education, research, and habitat protection, these efforts aim to ensure a harmonious coexistence between humans and crocodiles, while maintaining the region’s unique biodiversity.

While crocodile encounters can be exhilarating, it’s vital to prioritize safety and adhere to guidelines provided by local authorities and experienced tour operators. Respecting crocodile habitats, understanding their behavior, and following established safety protocols can minimize the risks associated with these powerful predators.

By appreciating the natural beauty and diversity of Darwin and the Top End while safeguarding the well-being of both humans and crocodiles, we can create a sustainable and enjoyable environment for all. So, embark on your journey to the land down under, where it’s always croc season, and enjoy the marvels of these ancient reptiles in their wild and untamed habitats.

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

The return of crocodile rule

Topic: Animal Science

A crocodile sunbakes on the banks of the Daly River. ( ABC News: Michael Franchi )

The Northern Territory's saltwater crocodile population has soared since the species was almost shot to extinction 50 years ago. Now crocs are getting bigger and edging closer to urban centres.

In the hothouse blooms of Australia's tropical north, these canopies have been hiding a big secret.

Underneath, in January this year, wildlife rangers removed a crocodile nest.

The discovery was less than 1 kilometre from the suburban fringes.

The nest was found at the edge of Palmerston, a city of approximately 40,000 people, about a 15-minute drive south of Darwin.

Rangers in the Northern Territory are used to seeing crocodiles on their patrols. In the past 50 years, saltwater crocodile numbers in the NT have grown from 3,000 to 100,000.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that this article may contain images of people who have died.

But this was the first time the saltwater crocodile, one of the deadliest predators on the planet, had been recorded laying eggs within 50 kilometres of the NT's capital city.

The find baffled Ian Hunt, a crocodile ranger with the NT government.

"It's really bizarre to find a nest up here … It's real close," Hunt says.

Yusuke Fukuda, a leading crocodile researcher in the Territory, is working to find out where the crocodile has come from.

To unravel the mystery, in his laboratory Fukuda takes a DNA sample from the hatchling.

Hundreds of crocodiles are trapped in Darwin Harbour each year, and Fukuda is building a database that maps their origins.

He says the nest discovery near Palmerston is a sign the Top End's migratory crocodiles are pushing into new places.

"I think it means good crocodile breeding habitats are getting saturated," he says.

"We might be finding more and more nests where we think they should not be, or where we do not think they would be."

Survival instinct

At Crocodylus Park, a tourist attraction on the outskirts of Darwin, park owner and croc expert Grahame Webb points to one of his biggest crocodiles.

"Crocodiles are predators, serious predators, and they've been preying on … people all through human evolution," he says.

Crocodiles, and experiences like a croc cruise at Webb's park, are synonymous with the Territory.

But for a long time, it was rare to see a large crocodile in the wild in the NT.

Only 50 years ago, large numbers of saltwater crocodiles were being killed by hunters, as depicted in this vision from the National Film and Sound Archive.

Hunting pushed crocodiles to the brink of extinction in the NT.

It was estimated at the time that from the end of World War II, 113,000 crocodile skins had been exported from the NT.

It left the croc population teetering at a perilously low 3,000.

But a hunting ban, introduced in 1971 in response to fears the lucrative resource would vanish and evolving societal attitudes to wildlife protection, saved the species from extinction.

The NT's crocs have now been a protected species for decades.

Yearly monitoring reports indicate there are now 100,000 saltwater crocodiles swimming around the NT.

Experts say while the crocodile population has stabilised, crocodiles are getting bigger on average each year as more of them reach maturity.

NT government monitoring of Top End rivers has found a shift in the total weight of crocodiles observed.

"In broad terms, there has been a decline in the proportion of crocodiles in the 1-to-3-metre size range in the population in recent years, and increases in the proportion of crocodiles in the 3-to-4-metre size range and in the proportion greater than 4 metres in length," a 2019 monitoring report says.

In the NT's waterways, big crocs are abundant in places where Territorians once swam without fear.

Living with crocodiles

Contact between humans and crocodiles in the wild doesn't get much closer than on the Top End's Daly River, about 220 kilometres south of Darwin.

This kind of protected landscape is the lure for many visitors to the NT.

The river is a mecca for barramundi fishers.

Pulling big fish out of a croc habitat into little boats, anglers are particularly alert to the re-emergence of the species.

"We don't want to count [croc] numbers anymore," Rob Cook, a fisher on the Daly, says.

However, increasing croc numbers is not the only thing concerning anglers.

"They seem to interact a lot more with boats now than they used to," Cook says.

These trends are making some on the water nervous, sparking calls for a culling program.

"Once I think they start doing that, the crocs will be a bit scared of the boats like they used to be," says Russell Walton, who fishes in the Daly every year.

Stuart Brisbane has made a living on the same river with his fishing business since the 1990s.

And he has seen the crocodile population soar.

"People used to swim in the river here," he says.

"But you wouldn't swim here now."

For Brisbane, however, culling would be contrary to the Territory way of life.

"The scenery, it's untouched. The birdlife, the crocodiles … there's not many places left that are like that."

Eyeing a crocodile swimming around his boat, he says he does not think humans need to take up arms again.

"It's their backyard, they live here," he says.

"If they're not causing a huge problem to us, why disturb them?"

However, overly familiar crocodiles — and calls for a cull — aren't new to the Top End's rivers.

The calls date back to the late '70s when, around the time of two fatal attacks, the notorious 5.1 metre "Sweetheart" began regularly attacking dinghies at a popular fishing spot.

Back in Darwin, wildlife researchers Erin and Adam Britton have been tracking crocodile attacks in Australia and around the world through their online database.

And they’ve discovered some trends in the data compiled from more than 5,250 incidents in Australia and overseas .

Erin says the data shows the likelihood of a crocodile attack rises the longer an area goes without an incident.

"We've found that the vast majority of crocodile attacks are occurring because locals feel quite comfortable with interacting with crocodiles in the environment and they're taking far more risks," she says.

From 2005 to 2014, 15 people were killed in crocodile attacks in the NT.

Since 2014, there have been only two fatal attacks, both in 2018.

Frightful beauty

Stunning sunsets are a staple of life in the Top End.

And when the raging heat of the day softens, and the sun descends on the horizon, this is when families flock to Darwin's beautiful beaches.

Beach-going is part of the lifestyle of many Territorians, despite full knowledge there could be deadly animals lurking in the water.

"The public is often complacent," the Northern Territory government's Parks and Wildlife Commission executive director, Sally Egan, says.

"I'm not comfortable that people are making the right choices necessarily.

"There are a lot of small children playing close to the water's edge on beaches, which truly makes me go cold to the bone.

"When it comes down to it, is the behaviour of the public good enough for them to stay safe, such that we won't have another fatality in the next little while? No."

Under the Northern Territory's crocodile management plan, rangers remove every crocodile found in waters around large populations.

But Egan warns that does not remove the risk of an attack.

Given the ever-present threat, Egan says it's the Northern Territory government's position that it cannot be responsible for public behaviour when it comes to crocodile risk.

"We can't keep you safe. You have to do it yourself," she says.

"That's part of why I need to publish as much information about what the risk is … so people can make their own choice."

Be Crocwise, the NT government's long-running public awareness program, warns: "Any body of water in the Top End may contain large and potentially dangerous crocodiles."

Crocodile kings

In Arnhem Land, rangers armed with long oars rush into a crocodile nest near Maningrida.

It's not egg-laying season when the rangers arrive at the nest, but the mother could still be lurking.

In case she emerges, they wield the oars to keep her at bay.

The mother has fashioned a network of grass channels into the nest from which she can attack.

Dirty water or shuffling blades of grass could be signs the rangers have company.

"She hides herself there in the grass," Bawinanga ranger Greg Wilson says.

"That's a track here going in, straight up to her nest."

For decades, the rangers have been conducting crocodile egg collecting, which helps keep croc numbers down.

"There's too many crocodiles right now," says Wilson, who has been collecting eggs since 2003.

But it's also a good earner for the rangers, whose collected eggs will hatch in crocodile farms around Darwin.

These farms are estimated to contribute more than $100 million to the Northern Territory's economy.

Aboriginal rangers and traditional owners such as Wilson are permitted to trap, relocate or shoot problem crocodiles.

For traditional owners like Jonah Ryan, such decisions are complicated.

He has totemic connections to the crocodile through the songlines of his ancestors.

"I'm part of the crocodile, too," he says. "They are called Baru around Arnhem Land, and that's my grandmother's totem.

"When I was a kid, she used to tell me, 'One day you get the right to decide what to do with the crocodile.'"

Just 110 kilometres east of Maningrida, in Ramingining, local rangers are building Australia's only Aboriginal-owned crocodile farm.

The prototype farm is big enough for almost 1,400 crocodiles.

Community leaders have long advocated farming crocodiles as a way to create jobs.

"The old people, they've been talking about putting in that crocodile farm," says elder and Arafura Swamp ranger Peter Djigirr.

"Now they've passed away, and we were for a long time asking, and now we've made it."

Northern Territory croc farmer Mick Burns has wanted to see crocodile farms in remote communities for decades.

"[Indigenous Australians] have lived with this apex predator for thousands of years, and we learn more from them about crocs than we teach them," he says.

Burns is now in discussions with multiple Aboriginal communities to establish crocodile farms that are owned and operated by Aboriginal people.

'We're in uncharted waters'

As the crocodile recovery brings profits, it also raises questions about how humans and crocodiles will continue to live together for the next 50 years.

The discovery of a saltwater crocodile nest near urban Palmerston, Grahame Webb says, is a wake-up call for the NT government's crocodile management program, and shows more research on crocodiles is needed.

"The fact that some crocodiles have escaped detection and escaped capture and gotten into some hidden swamps where they are nesting just means the program probably needs to be looked at," he says.

"Is it achieving its aims?"

The NT government says its crocodile management program will be reviewed this year.

But to get the management program right, Webb says the NT's research capability and investment, once the envy of the world, needs a considerable overhaul.

"We have no research capacity [in the NT]," he says.

"There's no institutional commitment to research. We've lost all that."

For Adam Britton, humans are once again entering the unknown when it comes to crocodiles.

"I think we're in uncharted waters," he says.

"We're seeing higher densities of larger crocodiles, we're seeing crocodiles appearing in places that people haven't expected to see them before, we're seeing behaviours from crocodiles that we haven't seen before because they're now starting to act in a more natural way.

"I think there's a lot more that we need to learn over the next few decades to try and keep this relationship between people and crocodiles at a level that is acceptable."

Reporting: Emma Masters and Steve Vivian

Photography: Michael Franchi

Digital production: Steve Vivian

- X (formerly Twitter)

Related stories

'the real crocodile dundee': meet the old-school aussie croc hunters.

Topic: Crocodile Attacks

How Darwin's iconic five-metre croc Sweetheart got stuffed

Topic: Libraries, Museums and Galleries

Related topics

Animal Attacks

Animal Behaviour

Animal Science

Conservation

Environmental Management

Environmental Policy

Environmentally Sustainable Business

Miscellaneous Animal Production

Ramingining

- Science & Environment

- History & Culture

- Opinion & Analysis

- Destinations

- Activity Central

- Creature Features

- Earth Heroes

- Survival Guides

- Travel with AG

- Travel Articles

- About the Australian Geographic Society

- AG Society News

- Sponsorship

- Fundraising

- Australian Geographic Society Expeditions

- Sponsorship news

- Our Country Immersive Experience

- AG Nature Photographer of the Year

- View Archive

- Web Stories

- Adventure Instagram

Learning to live with a carnivore

How do you persuade a community to support the protection of a killer predator that silently waits in murky recreational waterways to occasionally ambush and tear apart people?

That was the dilemma facing ecologists in the Northern Territory in the late 1970s and early ’80s. After almost a decade of legal protection, the number of saltwater crocodiles around the 2m bracket was rising across northern Australia – as were attacks on people. Suddenly, after years of barely a sighting of the reptiles near Darwin, people were being killed or hideously injured in the jaws of crocs near the northern capital, and a 5.1m male, known ironically as Sweetheart, hit the headlines for terrorising tourists at a popular fishing hole, knocking them out of boats.

Politicians, community leaders and tourism operators screamed for a return to mass culling to make the newly self-governing NT safe from the huge carnivores, while the now-legendary croc researcher Professor Grahame Webb and other experts looked for creative ways to ensure the species continued to be protected. “The croc population was going up, the animals were getting bigger, and we were facing this impending collision course between humans and reptiles,” he recalls. “People were saying, ‘Those things eat cows, horses and people! Why do you want to protect them?’”