BBD header search block

Apply for a disabled person's travel pass.

Travel passes are issued free of charge by Travel South Yorkshire and entitle the holder to free travel within South Yorkshire on:

- local bus services, trams and trains

- Northern Rail services between South Yorkshire and West Yorkshire

- buses throughout England at off-peak times (these are between 9:30am and 11pm weekdays, all day at weekends and on Bank Holidays)

Qualifying benefit

If you receive one of the following, you will automatically qualify for a Disabled Persons Travel Pass. You must apply directly to Travel South Yorkshire providing evidence of your qualifying benefit.

- higher rate mobility component of Disability Living Allowance (DLA)

- Personal Independence Payment (PIP) standard rate mobility with an award of at least 8 points for Moving Around or Communicating Verbally

- PIP Enhanced Rate for Mobility (at least 8 points awarded for moving around)

- War Pensioner’s mobility supplement

If you have no qualifying benefit

If you live in South Yorkshire, you may qualify for a pass if you:

- are blind or partially sighted

- are deaf or without speech

- have a disability which has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on your ability to walk

- do not have arms or have long-term loss of the use of your arms

- have a learning disability

- have been or would be refused a driver’s licence on medical grounds (other than on the grounds of persistent misuse of drugs and alcohol)

- PIP standard rate mobility (at least 8 points awarded for planning and following a journey)

- PIP enhanced rate mobility (points awarded for planning and following a journey)

Travelling with a carer

If you qualify for a Travel Pass and are in receipt of:

- higher rate care component of Disability Living Allowance with some mobility

- PIP Enhanced daily living

- higher rate Attendance Allowance

Your Travel pass will allow one carer to travel with you for free.

Contact Customer Services

Want to talk to someone right now, is this page helpful.

You might also like… Blue Badge

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

About your privacy and cookies

We use cookies to help make our website and services better. You consent to our use of cookies if you continue to use this website.

You are here:

Disabled person's travel pass.

A disabled person's travel pass entitles people to free travel at all times within South Yorkshire on:

- local bus services, trams and trains

- Northern Rail services between South Yorkshire and West Yorkshire

- buses throughout England at off-peak times (between 9.30am and 11pm weekdays, all day at weekends and on bank holidays)

You can't use your pass to travel on trams outside of South Yorkshire.

Travel passes are issued free of charge by Travel South Yorkshire .

How to qualify for a pass

You'll automatically qualify for a pass if you're under the age of 66 and:

- you receive the Higher Rate Mobility Component of Disability Living Allowance (DLA)

- you receive Personal Independence Payment (PIP) with an award of at least eight points in either 'moving around' or 'communicating verbally'

- you receive a War Pensioner's Mobility Supplement

- you have a Blue Badge parking permit

If you qualify for a pass and also receive one of the following benefits, the pass you receive will allow a carer to travel with you free of charge as well:

- Higher Rate Care Component of DLA

- Higher Rate Attendance Allowance

- Enhanced Daily Living Component of PIP

Applying for a pass

If you automatically qualify you can apply online for a travel pass by setting up an account with Travel South Yorkshire.

You'll need to provide copies of:

- proof of your age

- proof of your address

- proof of entitlement

- a recent passport-sized photograph of yourself

For online applications you can scan and upload the documents. If you're applying in writing you'll need to enclose a copy of your documents with your application.

If you don't automatically qualify

You may also be eligible for a pass if you live in South Yorkshire, you're under the age of 66 and:

- are blind or partially-sighted

- are deaf or without speech

- have a disability that has a substantial effect on your ability to walk

- do not have arms or have lost the use of your arms

- have a learning disability (local council registered)

- have been refused a driver's licence or would have been refused on medical grounds (but not for drug or alcohol misuse)

If you're over 66 years of age you may still qualify for a disabled pass if you're blind or partially sighted or if you require a carer to assist you when travelling.

We provide a free checking service on behalf of Travel South Yorkshire to confirm whether people who don't automatically qualify are eligible for a travel pass.

You can ask us to check is you're eligible using our online form below. If you are eligible, we'll issue you with a letter of entitlement. You'll need to provide this to Travel South Yorkshire to prove you can apply for a pass.

You can either scan your evidence documents or take a photo of them when you complete our form. You'll need to upload:

- proof of your eligibility (disability)

- proof of your age (your passport, NHS card, driving licence or birth certificate)

- proof of your address (a Council Tax or utility bill, or your NHS card)

Only fill in our online form to check if you're eligible if you don't automatically qualify for a pass.

Please allow seven days from submitting your application and proofs for us to make a decision.

When you've received your letter of eligibility or you meet automatic criteria you need to apply online for a travel pass . If you can't apply online you can contact Traveline for more advice on (01709) 515151.

Renewing an expired pass

For advice about renewing, call Traveline on (01709) 515151 up to two months before the expiry date to check that you are still entitled to a travel pass. They will advise you if you need a letter of entitlement from us.

If you are eligible, you can renew your travel pass online or fill in a paper travel pass application form .

Lost or stolen passes

Contact Travel South Yorkshire if you have lost your pass or it has been stolen. There is a charge for replacement passes.

A - Z Directory

Apply for a travel pass

You may be entitled to reduced travel, or even free travel, on bus services, trams and trains within South Yorkshire if you are:

- under 16 year old

- aged 16-18 years

- need to use public transport to get to school

- a disabled person

- a senior citizen.

All of these passes are issued by South Yorkshire Passenger Transport .

To apply for the following passes you will need proof of entitlement from your local Council:

- disabled person’s pass

- disabled person plus carer pass

- visually impaired person’s pass

- visually impaired person plus carer.

This site requires a JavaScript enabled browser. Please enable Javascript or upgrade your browser to access all the features.

Disabled Person's Bus and Train Pass

What a Disabled Person's Bus and Train Pass is, whether you qualify for a pass, how to apply or renew your pass, and what to do if you lose your pass. Including information about senior bus passes.

With a Disabled Person's Bus and Train Pass you can travel for free:

- on buses, trains and trams in South Yorkshire at any time.

- on Northern Rail trains between South Yorkshire and West Yorkshire.

- on any off-peak (9.30am to 11pm) and all day at weekends and bank holidays on any local bus journey in England.

If you want to help with parking accessibility, you need to apply to the Blue Badge scheme .

Do I qualify for a Disabled Person's Bus and Train Pass?

You will qualify for a Disabled Person's Bus and Train Pass if you live in Doncaster and you meet any of the following conditions:

- You are registered with one of the following disabilities with Doncaster Council Social Services

- Partially sighted

- Physically disabled

- Without speech

- You have a Learning disability

- You have been issued a Blue Badge (for parking) by Social Services

- You are in receipt of the higher rate mobility component of Disability Living Allowance (DLA)

- You are in receipt of Personal Independence Payment (PIP) with an award of 8 points in either “Moving Around” or “Communicating”.

- You are in receipt of a War Pensioner's Mobility Supplement

- You have been refused, or had your driving licence taken off you on medical grounds (other than on the grounds of persistent misuse of drugs and/or alcohol)

- A doctor or other medical professional has recommended that you do not apply for a driving licence for medical reasons, for example, because you have epilepsy.

- You have a disability or injury that has a substantial and long-term effect on your ability to walk

How do I apply for a Disabled Person's Bus and Train Pass?

- the higher rate mobility component of Disability Living Allowance, or

- Personal Independence Payment (PIP) with an award of 8 points in either “Moving Around” or “Communicating”, or

- a War Pensioner's Mobility Supplement,

The Disabled Person's Bus and Train Pass Application is made online; Doncaster Digital Venues is a list of locations in Doncaster where you can access a computer to claim.

If you need to provide information to support your application please complete the Disabled Person's Bus and Train Pass medical information request form, which is in the Downloads and Resources area at the bottom of this page, and email the completed form to [email protected]

Once we have all the information we need, we will write to you and let you know whether you are entitled to a pass. If you are entitled, to obtain your pass you must apply for a pass online attaching a scanned image or a photograph of the award letter and other evidence they need. If you do not have access to apply online you can phone travel South Yorkshire on 01709 515151.

The 'with carer' pass

A carer may be entitled to travel for free with you if you already qualify for a pass and also receive any of the following:

- the higher rate care component of Disability Living Allowance, or

- the higher rate of Attendance Allowance, or

- the enhanced rate living component of Personal Independence Payment (PIP)

To apply for a ‘with carer’ pass, please provide proof of your Disability Living Allowance, Attendance Allowance or Personal Independence Payment.

The carer can be anyone helping you to travel, such as a relative, friend, support worker or professional carer. It does not have to be the same person every time.

How long does my Disabled Person's Bus and Train Pass last?

The expiry date is shown on the front of the pass. Your pass normally lasts for up to five years, or until you reach 66 years of age, whichever comes first.

If you are blind or partially-sighted, your pass will automatically be renewed.

How do I renew my Disabled Person's Bus and Train Pass?

What if i lose my disabled person's bus and train pass.

Contact Travel South Yorkshire by phone on 01709 515151, by post (address is above) or dropbox at the Doncaster Interchange. A charge is made for issuing a replacement.

You should also contact Travel South Yorkshire if your pass is stolen, damaged or your address details change. Stolen passes will be replaced free of charge if you have a police crime reference number.

Further details can be obtained from Travel South Yorkshire.

Looking to apply for or renew a Senior Bus Pass?

Downloads & resources.

Run this page through the AI Enrichment process?: No

Display your introduction over featured image?: No

Did you find this page helpful?

Sorry to hear that. why wasn't it helpful, did you try using our search or a-z to find what you wanted, please try our search or a-z first..

These facilities can be found in the header of every page:

Do you want us to follow this up with you?

By clicking Submit, you consent to us contacting you in the future via email about this issue.

- Transport and access

- Older people

TRAVEL SOUTH YORKSHIRE - SENIOR TRAVEL PASSES

South Yorkshire

With a Senior Pass you are entitled to free off peak travel on buses across England (plus additional concessions in South Yorkshire) through the English National Concession Travel Scheme (ENCTS).

Description

Eligibility .

- You must live in South Yorkshire

- From your 66th birthday

You can apply for your pass online up to 2 weeks in advance of when you qualify.

- Free travel on local bus services and trams within South Yorkshire between 0930 and 2300 on weekdays, and at any time during the weekend and on Bank Holidays.

- Half fare on Northern train services for travel between stations on the South Yorkshire rail network between 0930 and 2300 on weekdays, and at any time during the weekend and on Bank Holidays

- Free travel on buses in all other parts of England between 0930 and 2300 on weekdays, and at any time during the weekend and on Bank Holidays. (This pass is not valid on tram services outside South Yorkshire.)

- Free of charge (first issue)

- Free travel on Stagecoach services to hospital appointments before 0930 - please visit the Stagecoach website for further details.

Please be aware that no pass means that you could pay full fare.

Apply online...it's easy!

Set up a MyTSY account in your name (or log in if you already have an account)

Log in > Select Passes from the top menu > Concessions > Senior Pass

Complete all personal details and upload proof documents - visit our ‘What you need to apply’ guidelines page

Upload your photo – see the ‘Acceptable Photograph’ guidelines page as an unsuitable photo could delay your application

Check your order and go to checkout.

If all the details are correct your pass will be dispatched within 11 days of receiving your completed online application.

Apply by post

Download an application form (PDF, 511Kb)

Complete all personal details and post to the address below together with a photograph and photocopies of proof documents.

Contact Centre SYPTE 11 Broad Street West Sheffield S1 2BQ

If all the details are correct your pass will be dispatched within 25 days of receiving your completed application form.

Please note proof documents must be photocopies and not original documents as all documents are destroyed once the pass is ordered.

A completed application form can also be submitted by dropping it off at the Customer Service Desk at your local Travel South Yorkshire Interchange .

Pass Protection

Pass protection can be taken out against Senior Citizen Passes for £5 for the duration of your pass, up to five years.

This will enable you to replace your old pass free of charge should you lose it during the time in which it is valid.

Address details:

Published: 09 August 2019

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

- Department for Science, Innovation & Technology

Cyber security skills in the UK labour market 2024

Published 16 September 2024

© Crown copyright 2024

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] .

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cyber-security-skills-in-the-uk-labour-market-2024/cyber-security-skills-in-the-uk-labour-market-2024

This is a summary of research into the UK cyber security labour market, carried out on behalf of the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology ( DSIT ). The research explores the nature and extent of cyber security skills gaps (people lacking appropriate skills) and skills shortages (a lack of people available to work in cyber security job roles) using:

Representative surveys of cyber sector businesses and the wider population of UK organisations (businesses, charities and public sector organisations) [footnote 1] .

Qualitative research with recruitment agents, cyber firms and medium/large organisations in various sectors.

A secondary analysis of cyber security job postings on the Lightcast labour market database, as well as reviewing the supply of cyber security talent through sources such as the Higher Education Statistics Authority ( HESA ) and Jisc.

This is the sixth iteration of the research, which has been carried out on an annual basis since 2019. This report on the cyber security labour market is consistent with the key learnings from previous years. The main findings are as follows:

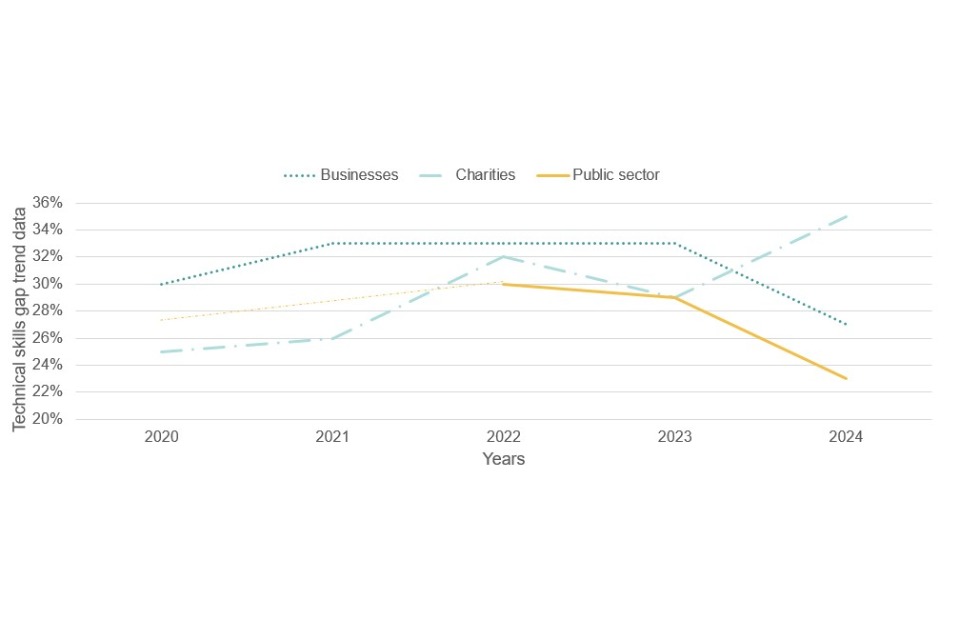

Across the economy, around half (44%) of businesses have skills gaps in basic technical areas. Incident management skills gaps have increased from 27% in 2020 to 48% in 2024.

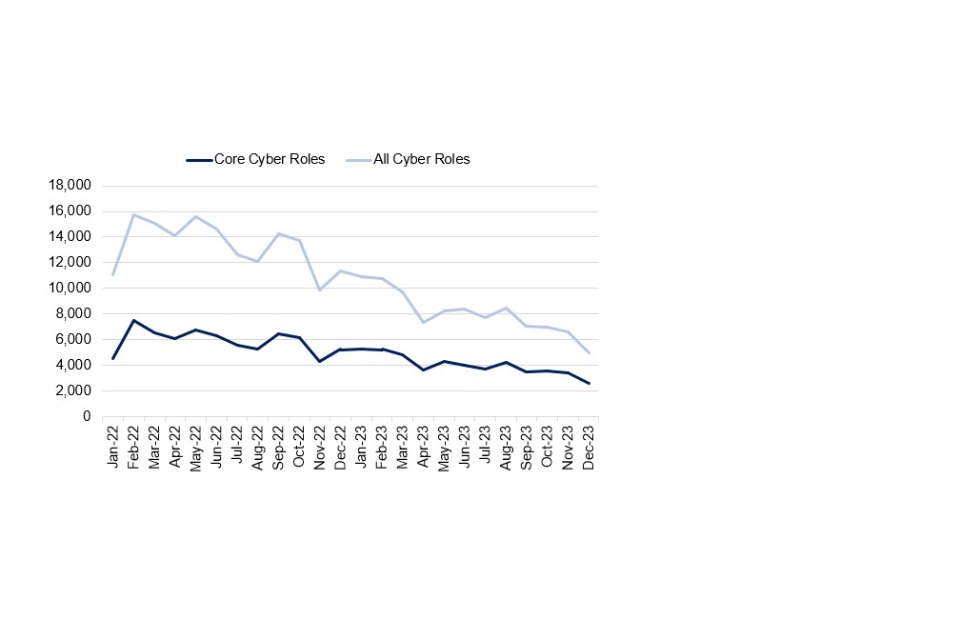

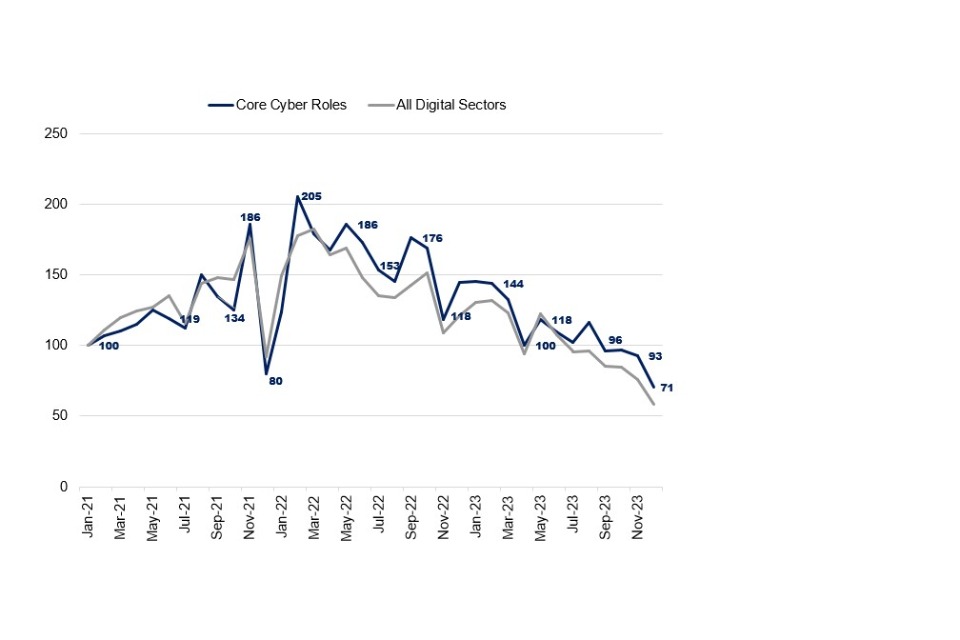

Demand for cyber security professionals has fallen, with core cyber job postings decreasing by 32% between 2002 and 2023. There have been challenging macroeconomic factors and job cuts in the technology sector, but cyber security has been more resilient than the wider digital sector.

The UK has made significant improvements in training new potential talent for the cyber security labour market and the number of cyber security graduates has increased by 34%.

Skills gaps

The proportion of UK businesses with basic and advanced technical skills gaps has not changed significantly across the 6 years of data. We estimate that approximately 637,000 businesses (44%) have a basic skills gap, where employees responsible for cyber security lack the confidence to carry out the basic tasks laid out in the government-endorsed Cyber Essentials scheme, and are not using external cyber security providers for these tasks. Approximately 390,000 businesses (27%) have gaps in advanced skills, such as penetration testing. These are skills which are not outsourced, and which are considered important (i.e. appropriate for businesses with more complex cyber security needs).

We estimate that 30% of cyber firms in 2024 have faced a problem with a technical skills gap, which is lower than in 2023 (49%). There has been a significant decline in reported skills gaps across many areas, for instance security testing (23%, down from 35%). In contrast, the skills gap for cryptography and communication security has increased (24%, up from 12%).

In the qualitative research, employers and recruiters thought that AI is likely to have a major impact on the cyber skills landscape, although there was a great deal of uncertainty about what the future will look like. Four potential changes were identified; increasing automation of cyber tasks (which could lead to job losses), the need for skills to understand and act upon AI tools, roles becoming ‘ AI cyber’ rather than just ‘cyber’ and the emergence of deep specialisms such as ‘cyber security machine learning.’

The diversity of the cyber sector workforce is consistent with previous years. There were signs of an upward trend in 2022 for women and people from ethnic minority backgrounds but this has not been sustained. People from ethnic minority backgrounds make up 15% of the sector workforce, and 9% of those in senior cyber roles (i.e. requiring 6 or more years of experience). 17% of the workforce are female and women account for 12% of senior roles. 13% are neurodivergent, and this group makes up 8% of senior roles. 6% are disabled, with 4% in senior roles. This suggests that diversity remains an embedded and persistent challenge in the UK’s cyber security workforce.

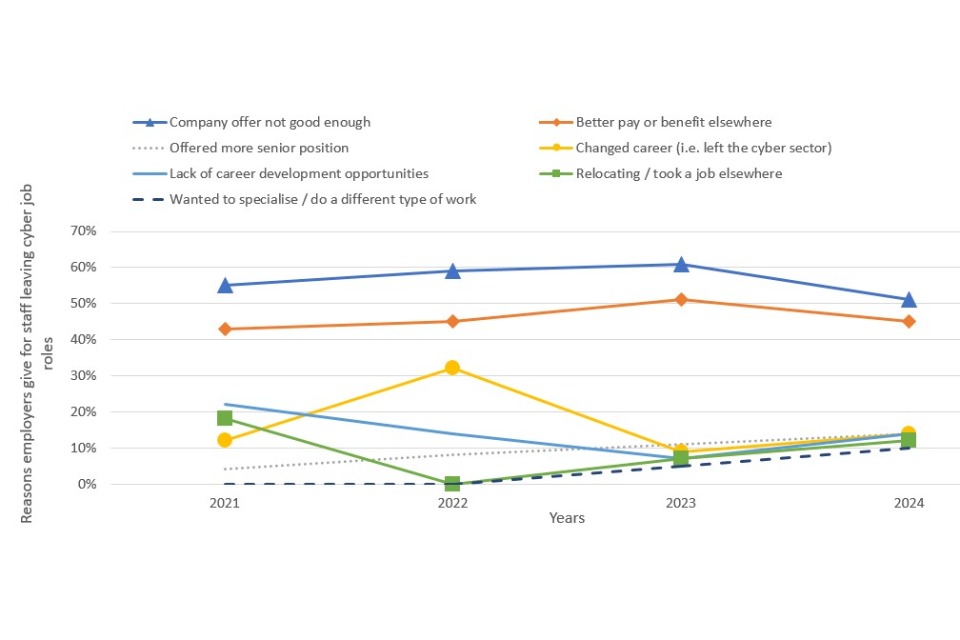

Recruitment and staff retention

Demand for cyber security professionals has fallen, a trend reflected across the digital and wider sectors. This decline has taken place against a backdrop of challenging macroeconomic conditions and technology layoffs worldwide. The number of core cyber job postings has decreased by 32% (from 71,054 in 2022 to 97,319 in 2023). Other job postings requesting cyber security skills have also decreased by 39%. However, whilst the number of vacancies has reduced, we estimate that employment in the cyber workforce has still increased by 5% within the last year (as new individuals enter the workforce and fill sustained demand for roles).

The number of students enrolled in cyber security courses has increased by 14% (from 18,270 to 20,890) and the number of students graduating in a cyber security course has also increased by 34% (from 4,330 to 5,790). In 2022/23 there were 580 new starts on cyber security apprenticeships in England, an increase of 18%.

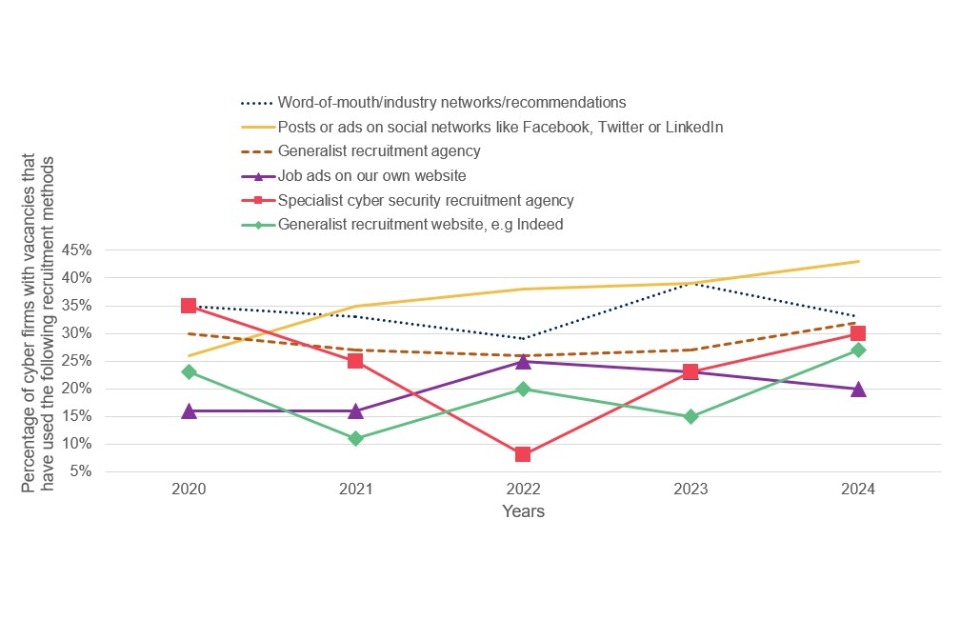

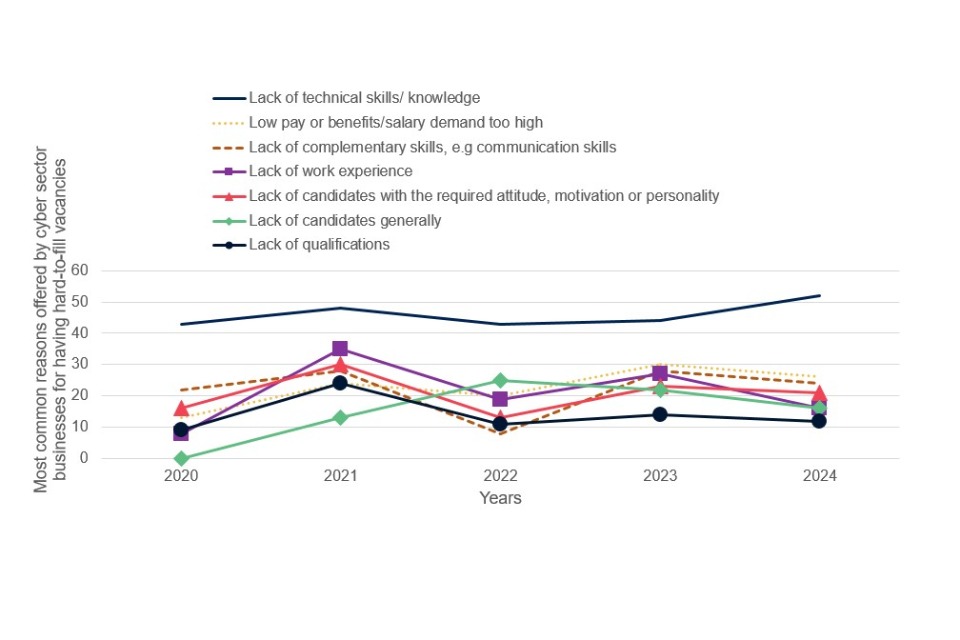

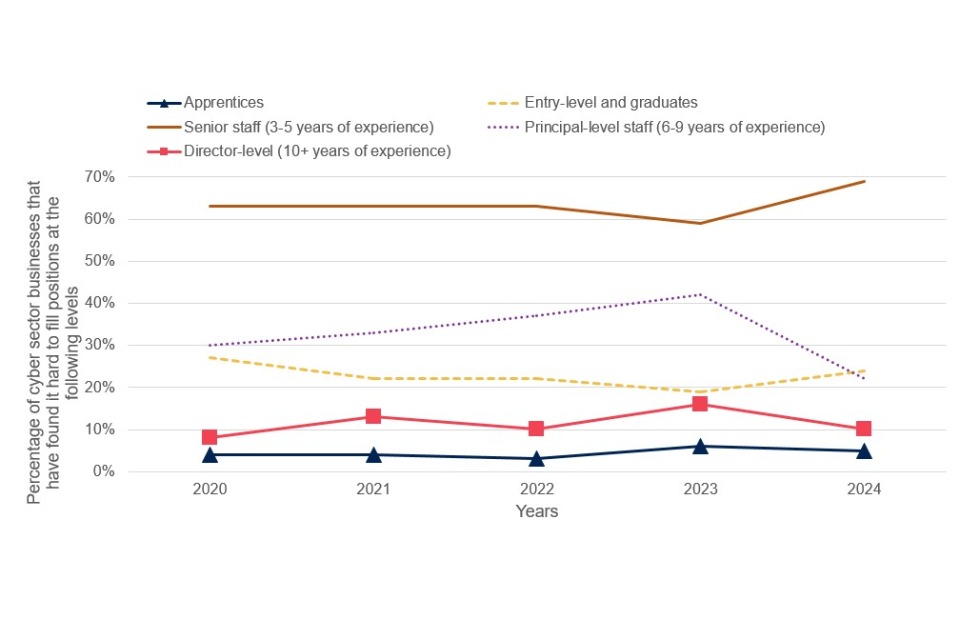

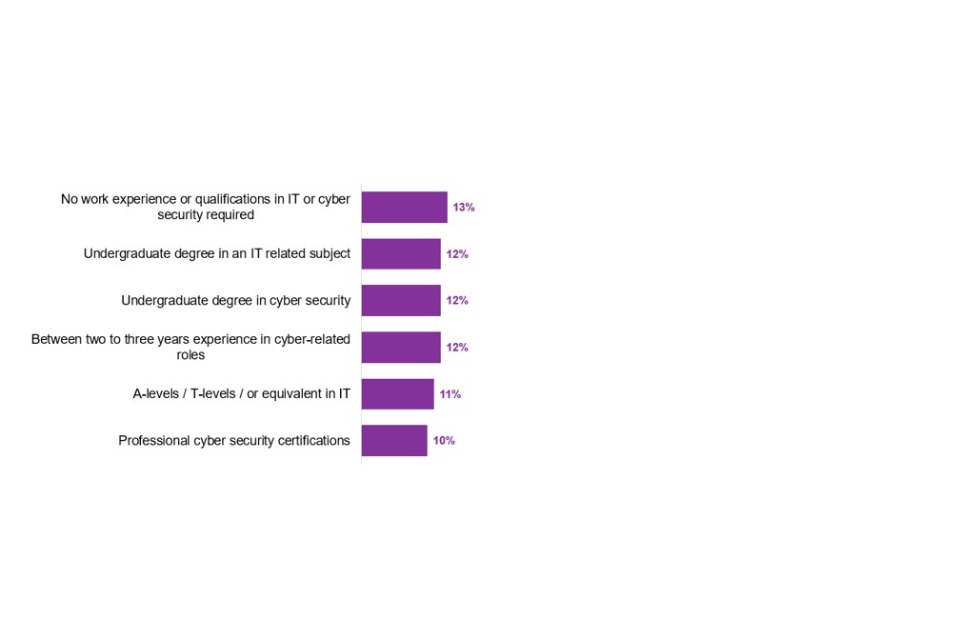

As with previous years, cyber sector businesses reported that they find positions for staff with 3 to 5 years of experience the hardest to fill and 61% of job postings request 2-6 years of experience. However, lack of work experience has become less of an issue for cyber sector firms who had hard-to-fill vacancies, declining between 2021 (35%), 2023 (27%) and 2024 (16%).

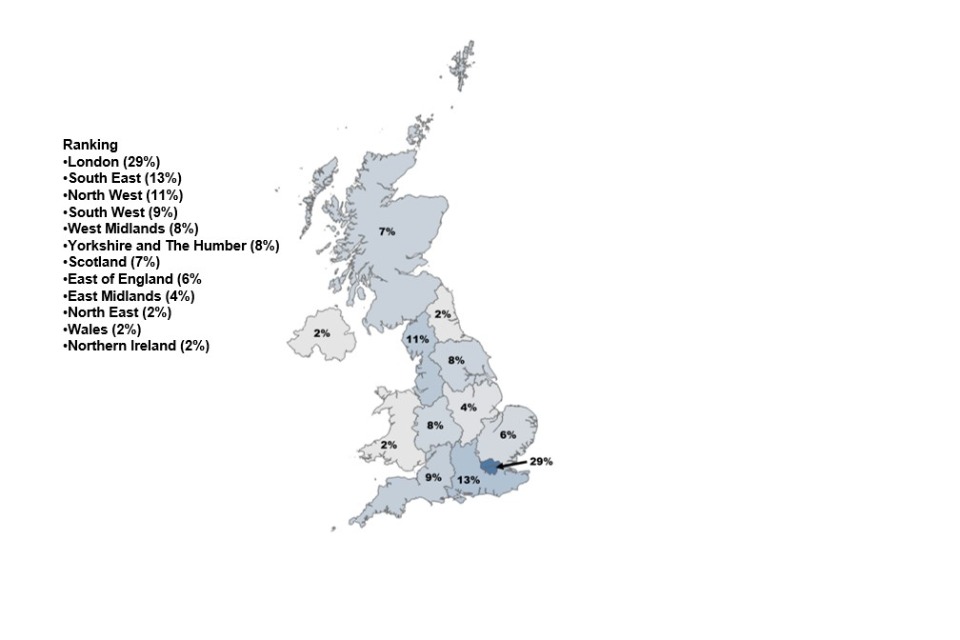

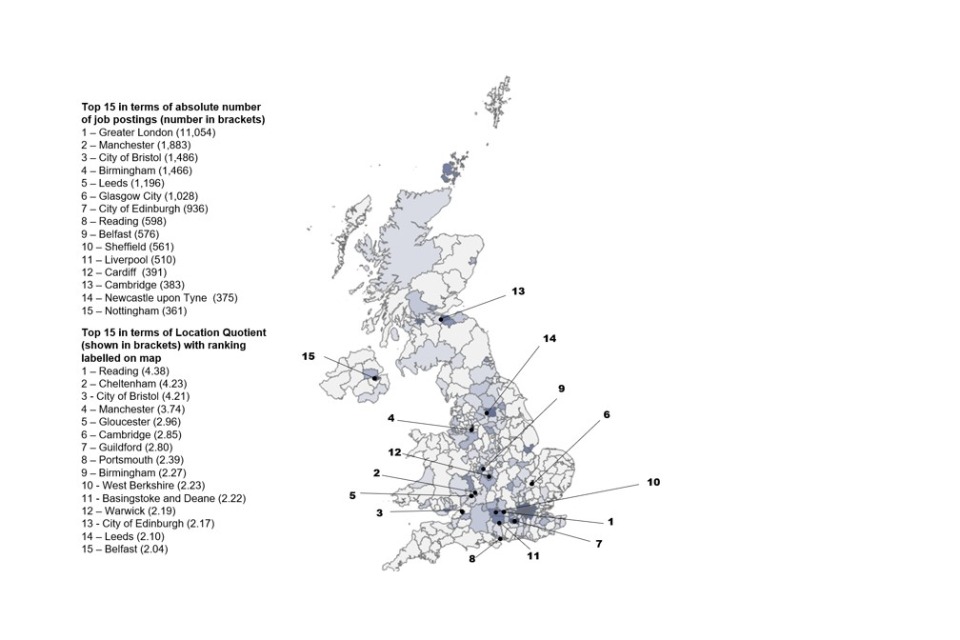

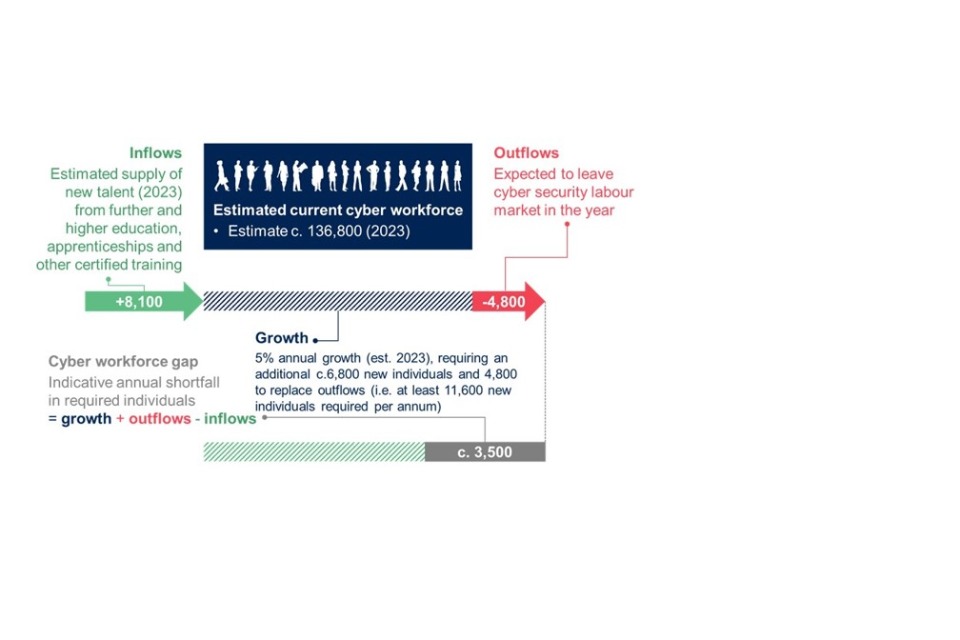

There is some evidence of a move away from remote working which had become widespread during the pandemic. In the qualitative research, some employers observed more people are returning to the office and recruiters said that clients are increasingly requiring candidates to be based in specific locations. This is reflected in the job postings analysis, where the proportion of postings with no regional location listed (i.e. the roles were marked as ‘Remote’ or ‘UK-wide’) has fallen from 28% to 22%. We estimate that there is a need for c.6,800 new people each year to meet demand, in addition to the c.4,800 to replace those exiting the sector, i.e. a total requirement of c.11,600 per year. A total of c.8,100 individuals entered the cyber security workforce in 2023, leaving an estimated shortfall in 2023 of c.3,500 people. This is lower than last year’s estimate of c.11,200. However, even though the workforce gap has decreased this year, the total shortage of cyber security professionals continues to grow each year as the unmet demand from previous years accumulates.

1. Introduction

1.1 about this research.

The Department for Science, Innovation and Technology ( DSIT ) commissioned Ipsos and Perspective Economics to conduct the latest in an annual series of studies to improve their understanding of the current UK cyber security skills labour market. In February 2023 the parts of The Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport ( DCMS ) responsible for cyber security policy moved to the new Department for Science, Innovation and Technology ( DSIT ). The previous study was published by DSIT in 2023 : (fieldwork in 2022). The studies prior to this were published by DCMS in 2022 (fieldwork in 2021), 2021 (fieldwork in 2020), 2020 (fieldwork in 2019) and 2018 (fieldwork in 2018).

The 2024 research, in line with previous years, aimed to gather evidence on:

- Current cyber security skills gaps (i.e. where existing employees or job applicants for cyber roles lack particular skills)

- Current skills shortages and the level and type of job roles they affect (i.e. a shortfall in the number of skilled individuals working in or applying for cyber roles)

- The role of training, qualifications, recruitment and outsourcing to fill skills gaps

- Where the cyber security jobs market is active geographically

- The roles being labelled as cyber roles versus ones that are not but require a similar skillset

- The role that recruitment agents play in the cyber security labour market

- Diversity within the cyber sector

- Staff turnover in the cyber sector

- Statistics on the size of the UK’s cyber security recruitment pool

- An estimate of the overall cyber workforce gap

- Recruitment agents’ views of the recruitment pool and how it has changed in the last year

For reference, any mention of ‘cyber’ throughout this report refers to the cyber sector. Any reference to ’cyber security’ refers to how individuals and organisations reduce the risk of cyber-attacks and is a component of working in a cyber sector role. Any reported change between years within this report is statistically significant to 95%.

1.2 Summary of the methodology

This section contains a brief outline of the research methodology. Greater methodological detail can be found in the accompanying technical report.

The methodology consisted of 4 strands:

Quantitative surveys – Ipsos conducted a representative telephone survey with 4 audiences: general businesses, public sector organisations, charities and cyber sector firms. The main estimates on skills gaps and shortages reported in this study are based on the survey data. Fieldwork was between 11th August and 10th November 2023.

Qualitative interviews – Ipsos conducted a more focused strand of qualitative research, with 28 in-depth interviews split across cyber firms, medium and large businesses and public sector organisations, and recruitment agents. The interviews explored the challenges these organisations faced in addressing skills gaps and shortages, and the approaches they were taking on recruitment, training and workplace diversity. Interviews took place between September and November 2023.

Job vacancies analysis – Perspective Economics analysed cyber security job postings on the Lightcast labour market database, showing the number, type and location of vacancies across the UK. This also covers remuneration, descriptions of job roles and the skills, qualifications and experience being sought by employers. This work primarily covered vacancies across the 12 months of 2023, supplementing the work done in the 2023 study (which covered vacancies from January 2022 to December 2022).

Supply side analysis – Perspective Economics replicated the methodology used on the 2021 cyber recruitment pool research to estimate the overall size of the current recruitment pool, as well as those likely to be entering the pool within the next 12 months (across 2023). This strand produces further statistics on the diversity, educational and occupational backgrounds, and salaries of this pool of labour, as well as outflows from the pool.

1.3 Acknowledgements

Ipsos and Perspective Economics would like to thank colleagues at DSIT for their project management, support and guidance throughout the study.

2. Who works in cyber security roles?

This chapter explores the people covering cyber security across organisations, including their career pathways into the role, their specialisms and the qualifications they hold.

For context, outside the cyber sector, we asked participating organisations to choose the staff member most responsible for their cyber security to complete the survey. Just like in the previous years’ surveys, these individuals are typically not cyber professionals.

2.1. Size of cyber teams

Cyber teams outside the cyber sector.

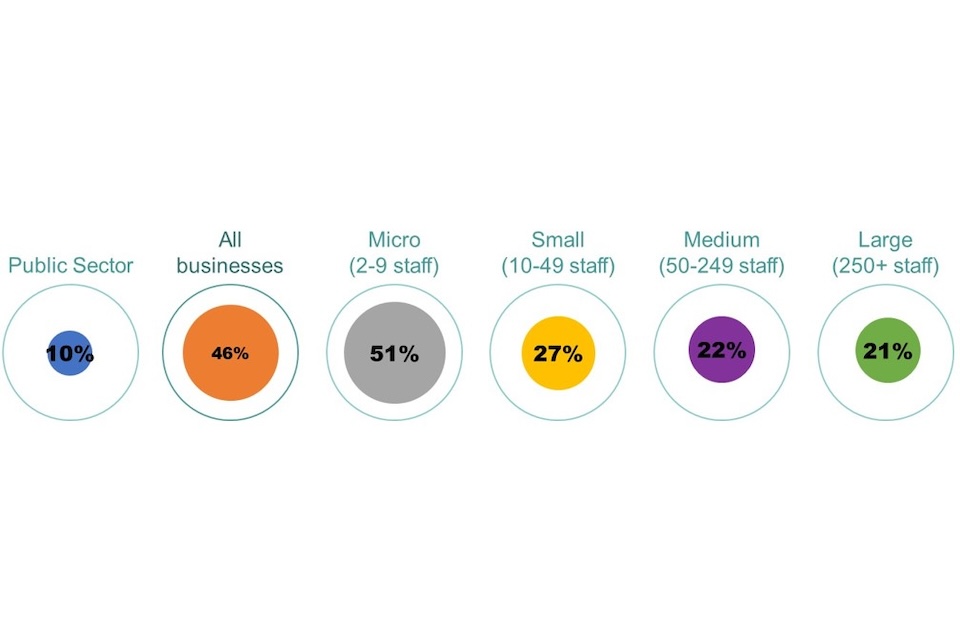

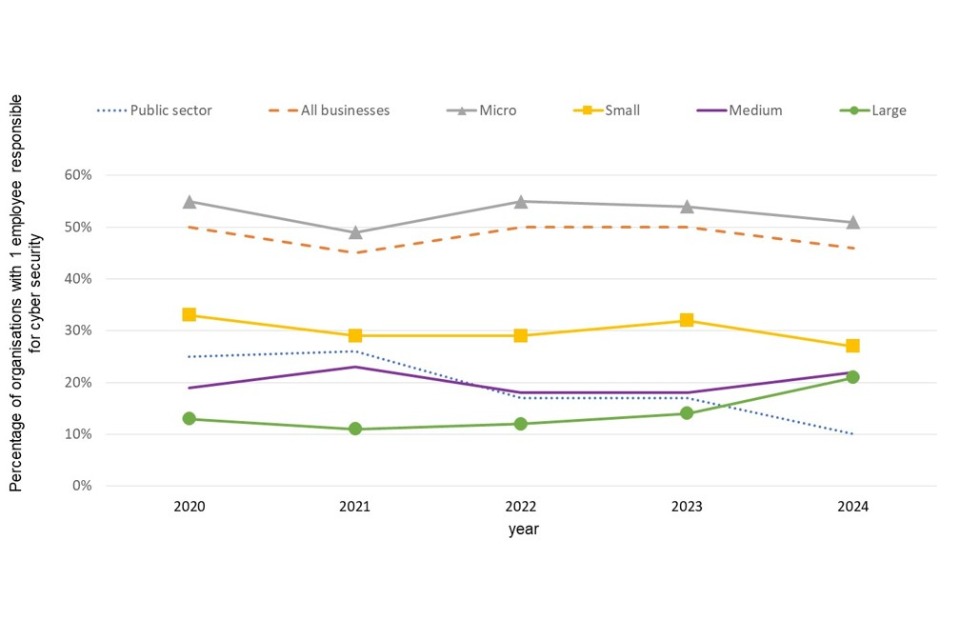

Just under half of business (46%) have 1 person involved in running or managing their organisations cyber security. For charities this is lower at just over a third (35%), however, the public sector appears to be the best resourced when it comes to cyber security with only one in ten organisations (10%) having a cyber security team of 1 person. Cyber teams seem to have a similar level of staffing to last year, the percentage of organisations having just 1 person to manage cyber security among the private (50%), public (17%) and charity (47%) sectors have remained stable. The median cyber team size for public sector organisations was 3 people while for private sector organisations it was 2.

Figure 2.1 demonstrates that larger businesses are more likely to have cyber teams of more than 1 person, as was found last year. Large, medium or even small companies are less likely to have teams of 1 person than micro-organisations. Among medium and large businesses, the median cyber team size was around 3. In line with last year, under a fifth of large (19%) and medium (15%) businesses had 4-5 people in these roles.

Figure 2.1: Percentage of businesses with just 1 employee responsible for cyber security

Figure 2.2: Percentage of businesses with just 1 employee responsible for cyber security (trend data)

Bases: 130 public sector; 930 businesses; 520 micro; 241 small; 121 medium; 48 large

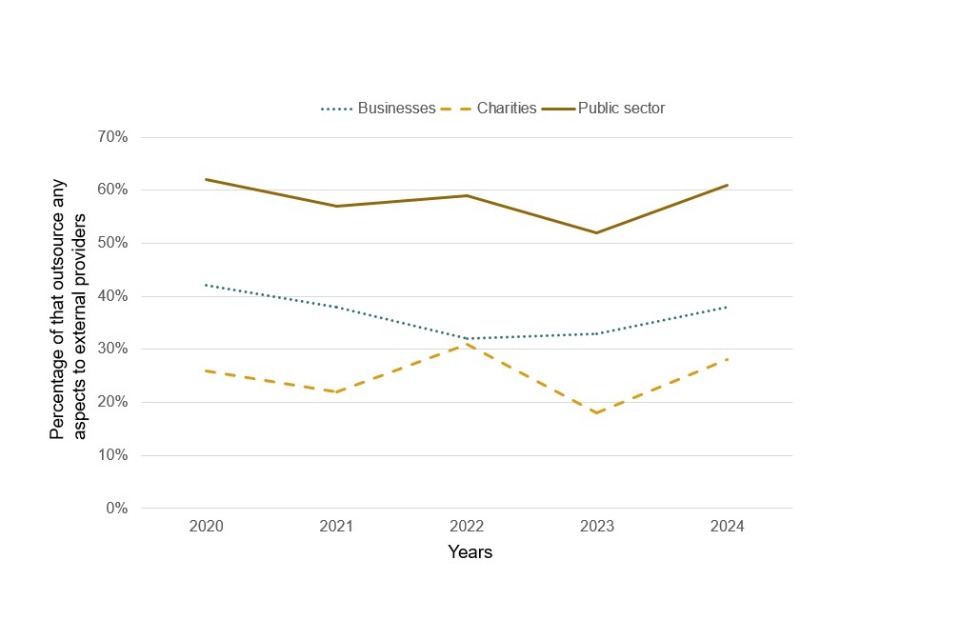

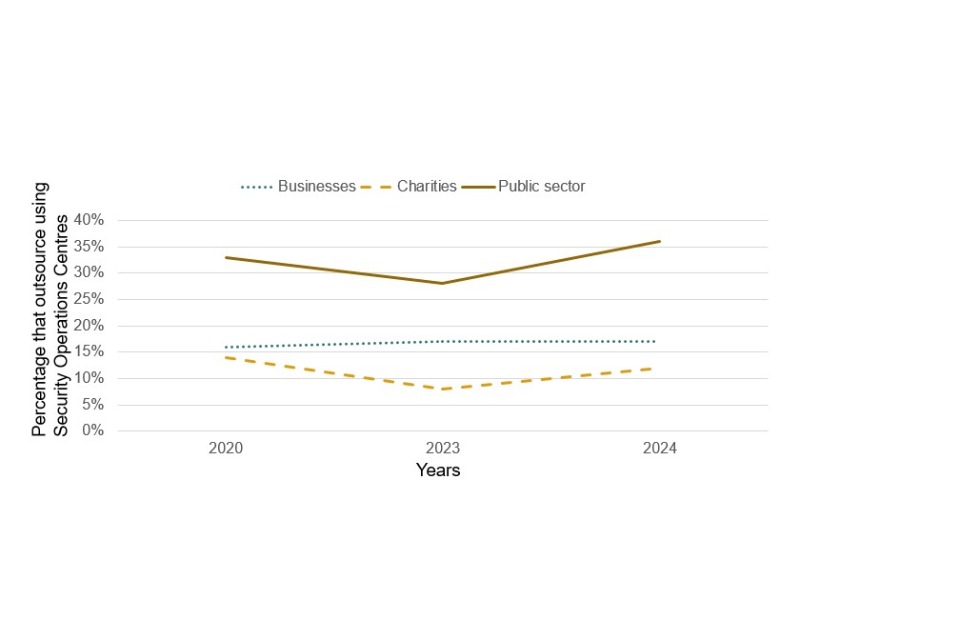

Among the private sector, those that outsource any aspects of cyber security to an outside organisation, meaning a business’s cyber security could consist of a mix of outsourced and non-outsourced tasks, tend to have cyber teams of more than 1 person. Nearly two thirds (64%) of those that outsource have a cyber team of more than 1 person versus 46% of those who do not outsource.

These figures are in line with last years’ findings in which 58% of those that outsourced had more than 1 person versus 43% who did not outsource. Therefore, an explanation for this could be similar to last year that this is because larger businesses are more likely to outsource cyber security. While 38% of businesses outsource, this increases to 65% among large businesses. This trend was also found last year with 33% of businesses outsourcing increasing to 62% for large organisations.

Cyber teams within the cyber sector

The cyber security sectorial analysis for 2024 found, like last year, most firms within the cyber sector in the UK this year are small (24%) or micro (55%) in size. The percentage of micro firms is unchanged from last year (55%) however, there has been a significant decrease in the proportion of small businesses compared to last year (27%).

The percentage of cyber sector businesses employing cyber teams of certain sizes has remained similar to last year. Only a minority of cyber sector businesses have a cyber team with 30 or more people.

Figure 2.3: Percentage of cyber sector businesses employing cyber teams with the following number of people

2.2. Career pathways into cyber roles

Career pathways into cyber roles outside the cyber sector.

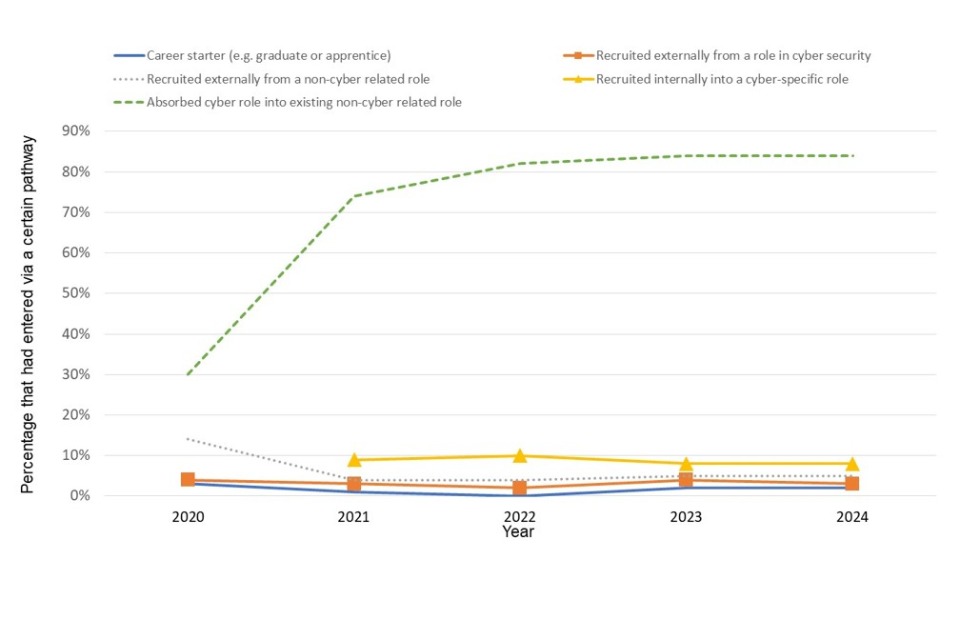

Among businesses outside of the cyber sector, 84% reported that cyber security roles within their organisation had been absorbed into an ongoing non-cyber security related role (Figure 2.4) showing no change from last year.

In the qualitative research, cyber security leads who were not dedicated specialists had typically taken on cyber responsibilities as part of a wider role, for instance, overseeing IT for the business or being Head of IT. Consistent with previous years, they could feel stretched and unable to dedicate enough time to cyber security.

There is too much work for one person. In addition to the technical side of it, we are in a constant cycle of auditing, PSN connection compliance, looking at business continuity across the organisation.

(Public sector organisation, 250-999 employees)

Cyber security leads who were taking on cyber security along with other responsibilities often learned on the job.

I cover a bit of everything in my role. For cyber security, I had not got any experience of that before starting this job. I have only learnt in this job.

(Private sector organisation, 50-249 employees)

Where they had done any training, this was through vendors (e.g. Microsoft) or publicly available resources such as the National Cyber Security Centre’s online training or YouTube videos. As we have found in previous years, cost and time are barriers to training.

So, it’s a lot of online [training] and in some cases the best resource is YouTube because it’s got such a massive user base. There’s a lot of people putting a lot of good information out there. Obviously, you just have to be careful what you’re looking at, it’s best to look at the verified sources.

Organisations were unlikely to recruit someone externally into a cyber specific role who was already working in a cyber security related role (3%). This number is similar to last years’ (4%), and shows organisations are still reluctant to hire external cyber security talent, preferring to include cyber security responsibilities in the roles of current employees.

Figure 2.4: Percentage of those in cyber roles outside the cyber sector who have come in through particular career pathways from 2020-2024

Bases: All businesses; 2024: 1060; 2023: 1108; 2022: 1070; 2021: 1041; 2020: 1152

Are cyber roles labelled as such across organisations?

Among charities, cyber security was mainly covered informally (83%) with only 14% of charities reporting cyber security was a formal part of their a job description, charity income however did affect these figures with fewer charities with an income of £500,000 or more (65%) cover cyber security informally than charities with an income of under £100,000 (89%), while for just under a third of charities with an income of £500,000 cyber security was a formal part of their job role (31%) compared to 8% for charities with an income under £100,000.

As with charities, most businesses covered cyber security informally (90%) but this was less common among public sector organisations with only one in two covering cyber security informally (50%). While large (41%) and medium (28%) businesses were more likely to have cyber security as a formal part of their job description than micro or small organisations (7%).

In the qualitative research, we heard two reasons why cyber security roles are undertaken informally. One is that there is no perceived need for a dedicated cyber security person in the organisation.

Cyber security is part of my job description. They don’t want to or need to go in the direction of employing a cyber security specific person.

(Public sector organisation, 50-249 employees)

The other is that there is a need, but this has yet to be recognised by senior management.

I don’t have a cyber security person in my team. I am picking up that role with the other responsibilities I have in the business. I would love to have a specialised cyber security person in my team. For a company our size, we do need one. That is what I am taking to the board members.

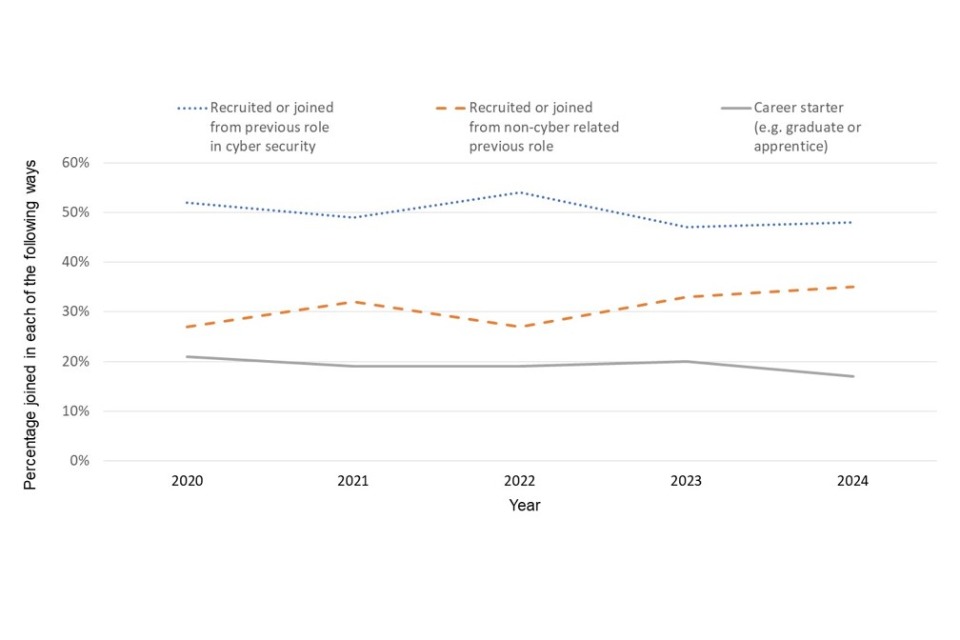

Just under half of those in the cyber sector workforce joined from a previous role in cyber security (48%). This figure has remained close to half since this question was asked in 2020 as shown by Figure 2.5. This year around a third of the cyber workforce had been recruited from non-cyber security related roles (35%), again this is similar to last year (33%).

Less than one in five of those in the cyber workforce had joined as a career starter (17%), this is broadly the same as last year (20%). As was the same in previous years, it is more common for cyber firms to take on those already in the cyber labour force (48%) than career starters (17%).

Figure 2.5: Percentage of cyber sector workforce who have come in through particular career pathways

Bases: 171 cyber sector businesses (excluding those that could not break down their workforce)

Are internships or work placements offered in the cyber sector?

Similarly, to the previous year just under a third of cyber firms (30%) had offered any internships or work placements. This figure has remained stable since this question was introduced, with it being 29% last year, 27% in 2021 and 28% in 2020. Like last year, this figure was higher among those that had been trying to recruit over the past year and a half (51%) compared with those who had not (11%).

2.3 Specialisms of those in UK cyber sector firms

Proportion of cyber sector workforce working in particular specialisms.

For the second year this research has included a question to measure the proportion of the workforce who work in the specialism outlined by the UK Cyber Security Council’s Careers Framework. Like last year, there is a high prevalence of Cyber Security Generalist with just over 6 in 10 cyber sector firms having a person in this role (62%). Once again, this year Digital Forensics and Cryptography and Communications Security had the lowest percentage of coverage across the cyber sector.

After Cyber Security Generalist, Cyber Security Governance and Risk Management made up the largest proportion of roles across the cyber workforce (46%), which is a slight change from last year in which Cyber Security Management was the second most common. The proportion of professionals who work in each of the specialisms has remained stable between 2023 and 2024.

Figure 2.6: Percentage of cyber sector workforce who work in each of the 16 specialisms outlined in the UK Cyber Security Council’s Careers Framework comparing 2023 to 2024

Bases: Cyber sector businesses where specialisms were specified; 2024: 144; 2023: 137

This year a question asking which responsibilities are considered to be part of a Cyber Security Generalist role was included. Cyber Security Generalists are often expected to have responsibilities across a range of cyber security areas. For cyber sector firms which said they had a Cyber Security Generalist role, just over eight in ten (83%) thought it was a generalist responsibility to advise IT staff and business managers on cyber security risks and controls including procedures and staff behaviours whereas just over half (51%) thought generalists were responsible to recruit, train and assess others in relation to cyber security.

In the qualitative research, we asked employers and recruiters what they understood by the term ‘generalist.’ A common definition was a single person or small cyber teams who have a wide range of cyber security responsibilities.

It’s a finger in lots of pies, but master of none! I would classify myself as a cyber security generalist.

(Public sector organisation, 1,000 or more employees)

Another common understanding of a generalist was a senior person, such as a chief security officer or consultant, who has to work across the whole field and understands both strategic and operational elements of cyber security. The role of ‘generalist’ was also associated with governance/non-technical roles.

I’d say quite a lot of us who are senior consultants are still generalist. Over my career I’ve looked at lots of different things, lots of different areas.

(Cyber sector firm, 1,000 or more employees)

Qualitative feedback on the UK Cyber Security Council’s Cyber Career Framework

Most employers and recruiters taking part in the qualitative research had not heard of the Cyber Career Framework or the 16 cyber security specialisms. Cyber firm employers were more likely to have some awareness of the Framework.

Employers and recruiters thought there were benefits to using the Cyber Career Framework. Some felt it could be helpful for people thinking about working in the cyber sector or just starting out on their career because it explains what the various roles in cyber security involve.

If I put myself in any of those kids’ shoes, security as a topic to them is security, but what actually is it? That Framework breaks it down into more granular roles and if they read it, it would give them a bit of an understanding to say security engineering does this, you make things work, you talk to the business, stuff like that. It gives them that granularity and tries to bring it to life for them. Because when you’re looking at cyber, you almost don’t know where to start. That gives them that starting point.

(Recruitment agent)

As well as being a valuable resource for new entrants, some thought the Framework could usefully provide a shared understanding between employers and educational providers.

Being able to work using that framework as a collaborative framework between the employer and the college to say, well, let’s try and get as many of this or get all of these aspects in. It’d be great because there’s a common Framework for both of us.

Some non-cyber organisations thought that the Framework would be useful when recruiting for cyber roles, for instance writing job descriptions and providing guidance on questions to ask potential candidates.

I would use this in the interview process when interviewing a generalist person. I would have questions for the candidate around these different roles and responsibilities.

(Private sector organisation, 1,000 or more employees)

Employers saw advantages to using the Framework to help identify gaps for training within their organisation.

If my company was trying to improve its cyber security knowledge for its team, they could use something like this. The staff would be able to support our clients better in terms of asset management or incident management.

However, a few employers felt that neither the Framework nor the 16 specialisms were relevant to their organisation. They believed that it was better suited to larger organisations, or that their organisation did not need to know these skills.

It feels more aimed for a larger businesses, not one our size.

A few employers thought that, in practice, the 16 specialisms overlapped, and were not actually as distinct as the Framework portrays. One commented that the Framework siloes different roles.

My immediate concern is that siloing up something which is already fairly siloed. A lot of the work that we do with clients is trying to help them break down the silos in some of their teams. Anyone that works in security operations should understand vulnerability management, inclusion detection, threat intel, incident response. So, what is the difference between those roles? Is there really value in splitting them out?” (Cyber sector firm, 1,000 or more employees)

Overall, though, employers and recruiters felt positive towards the Framework and some said that it would be beneficial to raise awareness of it.

A broader promotion of that skills Framework, whether that’s through some industry heavy weights or people to promote that out in the industry. Being able to promote that would definitely be a good thing.

2.4 Qualifications of those in UK cyber sector firms

Prevalence of different types of cyber security qualifications

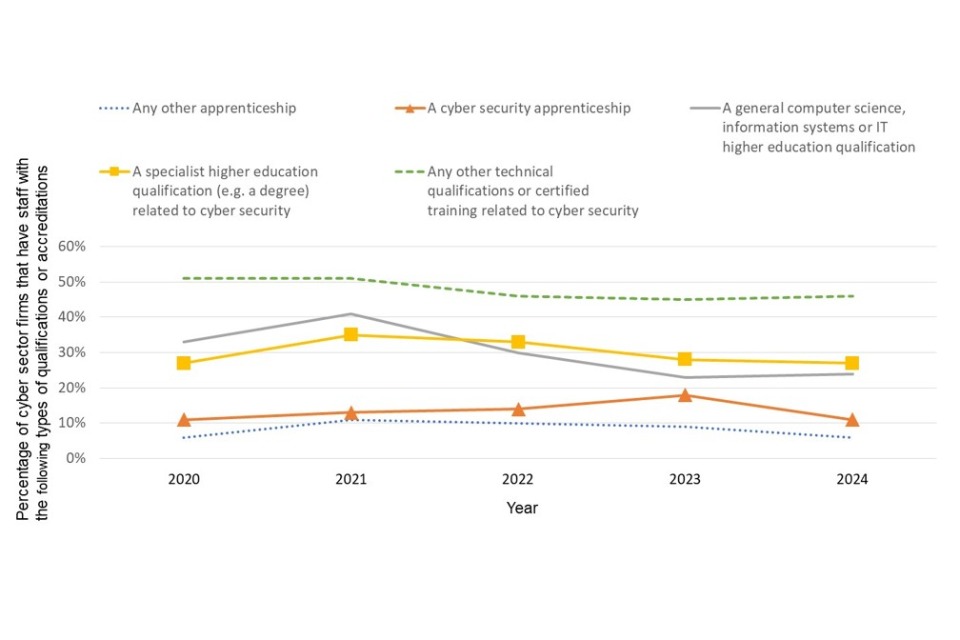

This year 63% of cyber sector firms reported they had any employee working towards a cyber security-related qualification or certified training. This finding is in line with both last year (61%) and the year before that (62%) indicating that levels are relatively stable across recent years.

Figure 2.7 shows the qualifications cyber firms say their staff hold. Like last year, just under half of all cyber firms (46%), whether they had or were working towards a qualification or not, said staff held a technical qualification or certified training. 27% of cyber firms said staff had a specialist higher education qualification almost identical to last year (28%). The number of cyber security apprenticeships (11%) has remained relatively stable compared to last year (18%). We look at apprenticeships in more detail in Sections 6.1 and 9.4.

Figure 2.7: Percentage of cyber sector firms that have staff with the following types of qualifications or accreditations

Bases: All cyber firms: 180; All with or working towards a qualification 114

Figure 2.8: Percentage of cyber sector firms that have staff with the following types of qualifications or accreditations (trend data)

Bases: All cyber firms: 180

Qualitative findings on professional standards and Chartered status for cyber professionals The UK Cyber Security Council has created the first professional standards for cyber security, against which cyber security training and qualifications will eventually be benchmarked. It has also created professional titles (including chartership) for various cyber security specialisms to indicate the level of competence of a professional. Professional titles are now available in Governance and Risk Management, Secure System Architecture and Design and Audit and Assurance through CIISec and Security Testing through The Cyber Scheme. Over 100 practitioners now hold professional titles. Titles for further specialisms will be released in due course.

As with the Cyber Career Framework, most were not aware of this route to the chartership, although employers from cyber firms were more likely to have heard of this.

Attitudes towards professional standards and the idea of chartership were mostly positive. Some felt this would provide standardisation to the cyber sector as is already the case for other professions.

There are professional standards for other roles, like accountants and surveyors for example. This will actually give employers the knowledge that they are dealing with qualified professionals, who have certain skill sets.

Similarly, some felt that chartership would bring credibility to the profession. It demonstrated to employers, as well as clients, that these individuals were well-qualified to undertake certain roles.

That would be very useful when recruiting to have these professional standards that people have to reach, and I presume they have to requalify regularly. You are not just taking their word for it, you have professional standards to go by.

Some had practical questions; how long chartership would take, how much it would cost, how requalification would work and how applicants would be assessed. A few were concerned that chartership would focus on academic ability at the expense of practical experience. Some wondered how chartership would fit with existing standards and accreditations.

Maybe over time I can see these coming into play, but there are already standards there, like you have your CREST certifications, ISC2. It’s understanding how these standards will fit into these. How do they correspond?

Some employers expressed a wait and see attitude, saying that they would only consider chartership if it became widely recognised by the industry or was requested by clients.

We may start using, provided customers were asking for it. 50% of our business is public sector and 50% is commercial, so it will be led by what industry wants.

Furthermore a few questioned whether chartership would be dynamic enough to account for the rapid changes seen in the cyber sector in comparison with other professions. The need to keep up to date was also raised in relation to the Cyber Career Framework.

Things we did 2 years ago are out of date already. You need to be dynamically chartered in cyber to understand everything that is coming down the line.” (Cyber sector firm, 1-9 employees)

3. Diversity in cyber security

This chapter explores diversity within the cyber workforce, focusing specifically on gender, ethnicity, disability, and neurodiversity [footnote 2] . It includes diversity estimates from the quantitative survey and qualitative findings.

As in previous years, survey questions on diversity are asked of cyber sector firms rather than the wider business population. As cyber firms are the primary recruiters and employers of cyber related positions and because most businesses carry out cyber roles informally, including businesses would give an inaccurate view of diversity in the cyber security workforce. The qualitative findings do include the perspectives of non-cyber organisations and recruitment agents.

3.1 Estimates of diversity in the cyber sector

All workforce statistics.

It is important to bear in mind that the data from this study are workforce level estimates derived from employer survey data. As with previous years, because these estimates can be very variable we checked for outliers but no outliers were identified this year.

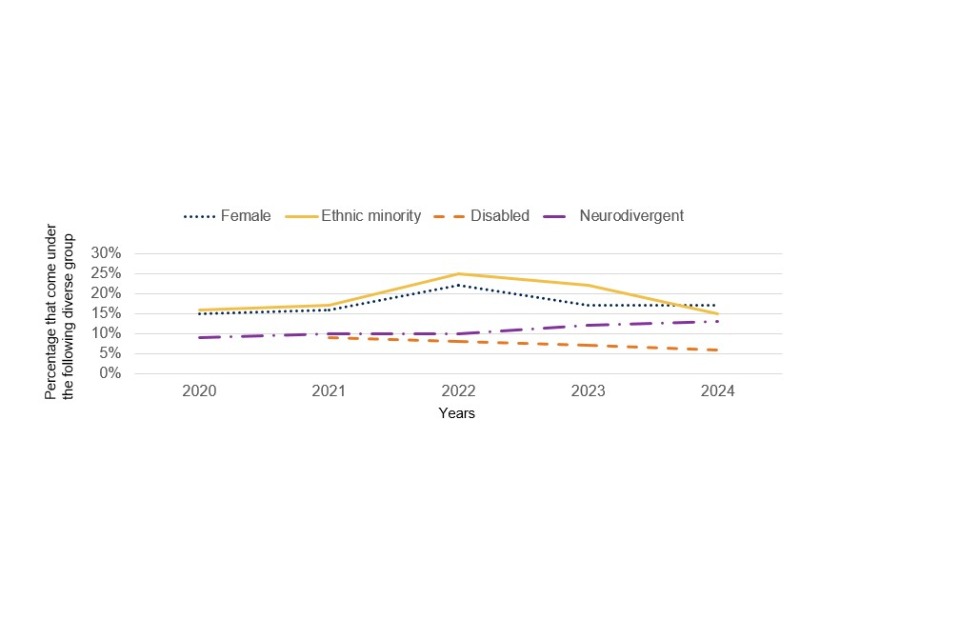

As can be seen from Figure 3.1, the proportion of women in the cyber workforce is 17%, which is lower than both the UK workforce as a whole and the digital workforce (although the gap is less marked). 15% of the cyber workforce are from ethnic minority backgrounds, which is in line with the UK workforce overall. In contrast, 6% are disabled [footnote 3] , which is lower than both the digital and the UK workforce, the same pattern seen in previous years. [footnote 4] 13% of the cyber workforce are neurodivergent. There are no reliable statistics to compare this figure to other sectors.

Figure 3.1: Percentage of cyber sector workforce that come under the following diverse group

Base: c140 cyber sector business for all workforce estimates (in each case excluding those that were not able to answer these questions, or refused)

The overall pattern is that there is a lower proportion of these demographics in senior roles compared to the cyber workforce overall. [footnote 5]

As Figure 3.2 illustrates, diversity in the cyber sector overall has remained stable compared to previous years. The female, ethnic minority, disabled, and neurodivergent proportion of the workforce has remained broadly consistent over the past five years. The start of an upward trend in 2022 for those from ethnic minority backgrounds and women has not been sustained and there are now signs of a downward trend for ethnic minorities. The share of neurodivergent workers is trending upwards over time.

Figure 3.2: Percentage of cyber sector workforce that come under the following diverse group (All cyber workforce trend data)

Base: c. 140-220 cyber sector businesses for all workforce estimates (in each case excluding those that were not able to answer these questions or refused)

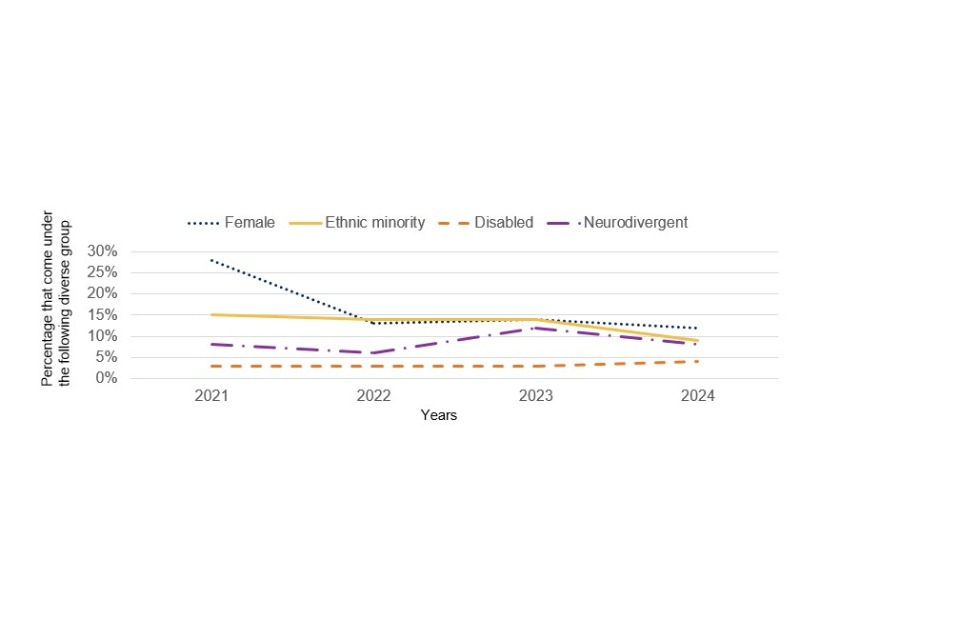

Senior workforce statistics

Senior cyber professionals are defined as those who have 6 or more years of experience. The latest study found no significant change in the level of diversity at a senior level in the past year. As can be seen in Figure 3.3, the proportion of disabled people in senior cyber roles has been consistently low over time. The proportion of women in senior cyber roles has been steady following a drop between 2021 and 2022.

Figure 3.3: Percentage of cyber sector workforce that come under the following diverse group (Senior cyber workforce trend data)

3.2 Attitudes towards workforce diversity

In the qualitative research, employers defined diversity in a variety of ways, including diversity in gender, ethnicity, disability, neurodivergence, sexuality, social class, religion, nationality and age. As we have found in previous years, employers did not perceive the cyber sector as very diverse, especially in terms of female representation and ethnicity, which tended to be the most common ways in which employers thought about diversity.

As an industry, it’s unnecessarily dominated by white men. It’s always important to make sure you’re giving [women and ethnic minorities] the opportunity to come in.

A related point is that perceptions of the industry can be shaped by the stereotype of white males in dark rooms.

There are insufficient role models in the industry. If you think in the cyber world, it is very white male-orientated, mid 20s, early 30s, drinking Red Bull in front of a screen. That is the stereotype.

(Cyber sector firm, 1-9 employees)

While employers saw lack of diversity in the cyber sector as an issue, some believed that the landscape is changing for the better.

It’s not very diverse but it is trying. The one that is most noticeable is around gender diversity.

This was echoed by recruiters, who said that employers are increasingly asking for diverse candidates. This is partly because diverse teams are valued for performing better.

I think it’s a really key thing. I think everyone recognises now that diverse teams are very much more high performing teams.

Some employers said that diverse teams are particularly important for cyber security because of the need to solve problems and continually counter threats.

Cyber security is very much about problem solving. When you drop a problem in a team of people, what you hope is that every single one of them will think of a different way of solving it. That’s the first part. The second part is that everybody feels comfortable enough to share.

(Cyber sector firm, 10-49 employees)

A broader factor is the desire to have a diverse workforce. One recruitment agent thought that this is particularly an issue for leadership roles.

For leadership roles, absolutely. If you’re a publicly traded company, there’s that pressure there to have diverse leadership. But even architecture or engineering roles, there’s definitely that pressure there to try and produce diverse short lists. We’re probably going to get our knuckles wrapped if, for instance, we sent a shortlist of, say, four or five people and they were all white males.

However, some cyber employers felt that although they were able to recruit diverse candidates for entry level and more junior roles, diversity at senior levels is a particular challenge. One way of countering this is having leadership and mentoring programmes for diverse employees.

We are broadly at parity in gender in our early years, recruitment in graduate and [their apprentice scheme]. We have a good ethnic diverse mix in those grades. As you get more senior, that tends to whiten out, and the number of men, or proportion of men, increases.

This is one example of the variety of inclusive practices which some cyber firms have in the workplace. Others are flexible working, internal forums, recognition awards for women in cyber, making adjustments for people with disabilities, and being mindful of religious festivals such as Eid. Some public and private sector organisations have similar diversity initiatives, but these are company-wide rather than specifically relating to the cyber workforce.

3.3 Diversity in recruitment processes

Just under half (47%) of cyber firms have tried to recruit individuals into cyber roles since January 2022. [footnote 6] Amongst these firms, 42% have taken some action to encourage applications from diverse applicants which is consistent with 2023 (40%). This means they have targeted at least one of these diverse backgrounds. 14% have taken action to encourage applicants from all the diverse backgrounds asked about in this study (women, people from ethnic minority backgrounds, disabled people, and neurodivergent people). This is also similar to 2023 (18%).

As can be seen in Figure 3.4, and similar to last year, cyber firms are most likely to focus their efforts to recruit women. As we have discussed, in the qualitative strand employers commonly associated diversity with a lack of female representation, which helps explain why recruitment efforts are more likely to be directed at this group. The proportion of cyber firms who have made changes to recruit from ethnic minority backgrounds and neurodiverse backgrounds has not significantly changed.

Figure 3.4: Percentage of cyber firms who have tried to recruit over the last 18 months and have made changes to recruit across the following groups

Base: 84 cyber sector firms who tried to recruit since the start of 2022

In a new question this year, we asked cyber firms about recent, specific steps taken to boost applications from diverse groups, focusing on those who adjusted recruitment for diversity. Although the base size (35 firms) is low, and therefore should be treated with caution, responses give a sense of the most commonly used strategies:

- 43% hired through non-degree routes

- 43% attended networking events/conferences and career programmes for diverse groups

- 40% took action to diversify the senior leadership team

- 40% worked with recruitment agencies to find more diverse candidates

- 37% ran talks or events in education settings

- 29% worked with third sector organisations to help identify and support more diverse groups

- 20% have hired through a scheme to promote diversity

- 20% set diversity metrics/quotas for recruitment In the qualitative interviews, employers mentioned having more inclusive job specifications, increasing diversity through entry level recruitment, using blind recruitment, setting quotas, using referral schemes, and recruiting from other countries.

We sketch our requirements. [Internal recruitment team] make sure that we are not using any offensive or challenging words or phrases. They word it in a considerate way to get a much broader response.

Recruitment agents said they use their networks to find diverse candidates and also work with organisations to ensure their job specifications are flexible and attractive. In terms of employer requests, some were informally asking for more diverse recruits, while others set specific quotas, particularly on the basis of gender. One recruiter said some organisations gave them incentives to find candidates with disabilities.

It can come down to education with the client as well. Being open and flexible on locations and working patterns and things like that. You flex on those things and therefore you can attract more diverse candidates.

In line with the qualitative findings from previous years, employers and recruiters felt that a lack of diversity in the talent pool is a major barrier to recruiting individuals from diverse backgrounds. Some employers felt that this is particularly an issue in their local region because it is not ethnically diverse.

I don’t think there is enough women in the industry to recruit from. Which is a challenge. There is still not enough women choosing it as a career option and I have been in this industry since the mid-80s.

As we have also found in previous years, some employers did not have any strategies in place beyond not excluding anyone on the basis of their background. For some, attracting more diverse candidates is simply not on their radar. Others said that they do not have the expertise or resources to do so.

We just recruit from whoever applied. It is not something that is not on the radar or off the radar. It just would not be a thing. We just go from the pool of applicants. No sort of discrimination.

We don’t positively discriminate, we just look for the best person who can do the job. We are not a large employer like the civil service, who employ thousands of people and can look at diversifying strategies. We just look for the best person for job.” (Private sector organisation, 1,000 or more employees)

4. Current skills and skills gaps

This chapter explores the cyber security skills that organisations feel they need and the extent of current skills gaps. Cyber security skills gaps exist when individuals working in or applying for cyber roles lack particular skills necessary for those roles. This is different from skills shortages, which are a shortfall in the number of skilled individuals working in or applying for cyber roles. We cover skills shortages with regards to recruitment in Chapter 6.

4.1 Technical skills gaps outside the sector

Basic technical skill gaps.

Each year, the survey asks cyber security leads within organisations to rate how confident they are in carrying out a range of basic cyber security tasks and functions. These functions comprise the technical areas covered under the Cyber Essentials scheme as well as other basic aspects of cyber security. Some tasks have been added since the launch of the initial survey.

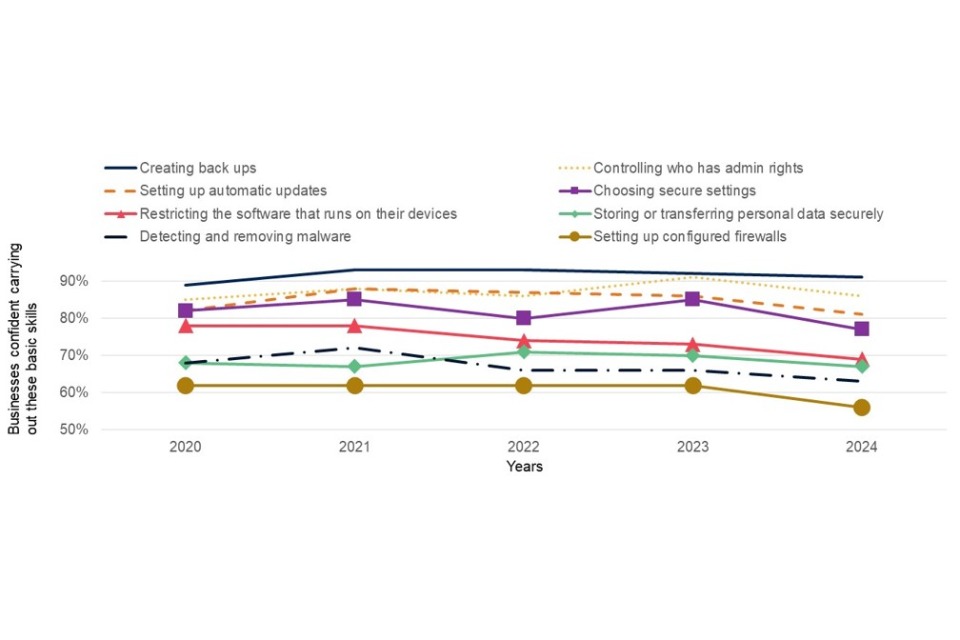

Figure 4.1 illustrates that confidence in carrying out these tasks has remained relatively consistent across all five years of the study, although this year has seen more significant declines than previously noted in some areas.

Figure 4.1: Extent to which businesses are very confident or fairly confident carrying out each of these basic skills gaps across all 4 years of the study (Base is where such tasks are not outsourced except for setting up new accounts and authentications)

Bases: c.600+ businesses that do not outsource each task

Figure 4.1, which focuses just on those businesses that conduct these functions in house, reveals that the areas of most prevalent skills gaps continue to be around the setting up and configuration of firewalls, detecting and removing malware and the secure storage and transfer of personal data. Even here, however, only a minority of cyber security leads across the business population – no more than one in five for any measure – say they are not confident in their business’s ability to carry out these tasks. Although the pattern broadly follows those of 2023, confidence in choosing secure settings and controlling who has admin rights has significantly decreased in comparison.

Figure 4.2: Extent to which businesses are confident in performing basic cyber security tasks (Base is where such tasks are not outsourced except for setting up new accounts and authentications

Bases: c.600+ businesses that do not outsource each task. Unlabelled bars are under 5%

In order to provide a more complete picture of the state of skills gaps in the total business population, Figure 4.3 also includes businesses that outsource cyber security, and separates organisations into different categories – businesses as a whole, large businesses (with 250 or more employees), charities and public sector organisations.

The results in figure 4.3 continue to show that a large minority of organisations lack confidence in several of the basic skills areas, and that basic cyber security advice and guidance is still needed for businesses outside the cyber sector. The most common area where organisations lacked confidence was a new code included in the survey for this year, a third of businesses and charities reported that they were not confident in dealing with cyber security breaches (33% of businesses and 34% of charities).

There are some changes this year when comparing the percentage of organisations not confident in certain basic tasks to the results in the 2023 study. Businesses this year were less confident in restricting software (22% vs 18%), choosing secure settings (15% vs 10%), setting automatic updates (13% vs 10%) and controlling who has admin rights (9% vs 6%). Meanwhile figures for large businesses remained mosltly consistent with last year, however more large businesses this year were not confident in setting up configured firewalls (13% vs 2%). There were no changes for charities and the public sector between this and last year.

Figure 4.3: Percentage not confident in performing basic cyber security tasks, by type of organisation

Bases: 930 businesses; 46 large businesses (with 250+ staff); 190 charities; 130 public sector organisations. N.B. these figures are rebased on the full survey samples, but the questions are only asked of a subsample. The subsamples are small for large businesses, charities, and public sector organisations (c.46+).

A combined basic technical skills gap indicator

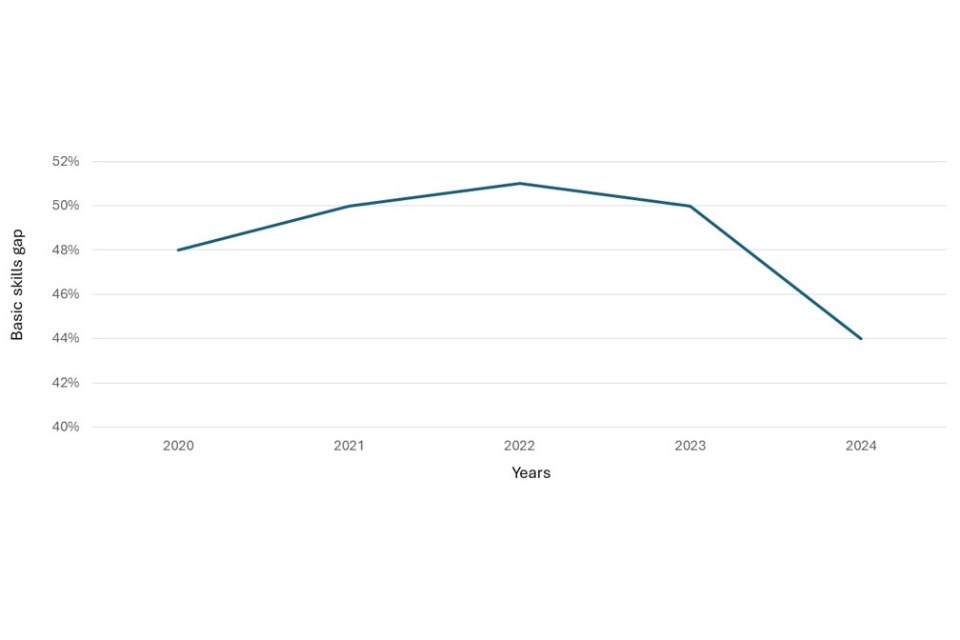

We can use these findings to estimate the proportion of businesses with a basic cyber security skills gap. We do this by combining all 10 tasks listed in Figures 4.1 and 4.2 and identifying the percentage of organisations that are not confident in undertaking at least one of these basic functions. This gives us an overall figure of 44% of businesses that can be said to have a basic technical skills gap. Once again, this is lower among public sector organisations (24%) and large businesses (26%) and higher among charities (51%).

The survey is designed to be representative of the UK business population. This means that we can extrapolate from our finding that 44% of businesses have a basic technical cyber skills gap and estimate that approximately 637,000 UK businesses have such a gap. [footnote 7] This is a significant fall from the 2023 survey, when 50% were estimated to have a basic technical cyber skills gap.

Figure 4.4: Basic skills gaps trend data

Bases: 930 businesses

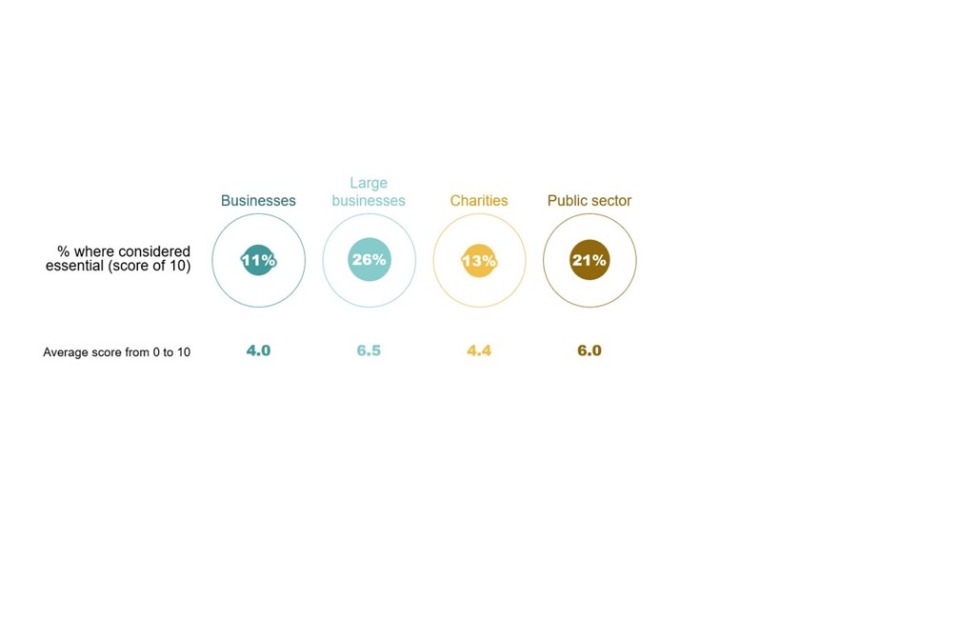

Beyond these foundational cyber security skills required for basic cyber hygiene, some organisations may judge that they also require more advanced technical skills to stay cyber safe. This may be because of the sector in which they operate, their clients, supply chain or partner relationships, among other factors.

The definition of advanced technical skills used here was based on data obtained from the 2018 cyber security labour market study. These are skills that may be important for organisations with more complex cyber security needs, and includes skills such as penetration testing, forensic analysis, interpreting malicious or user activity monitoring tools.

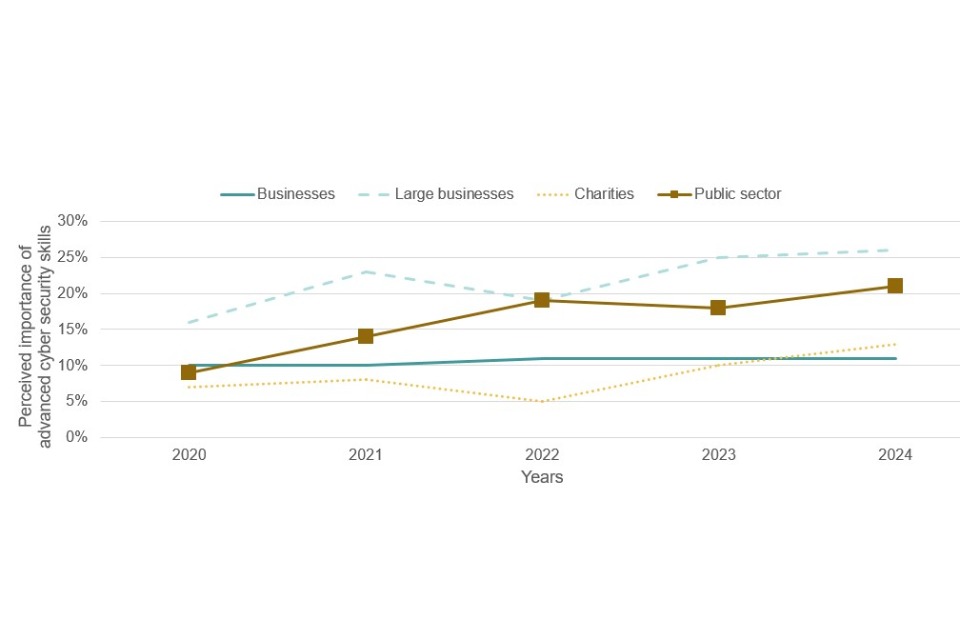

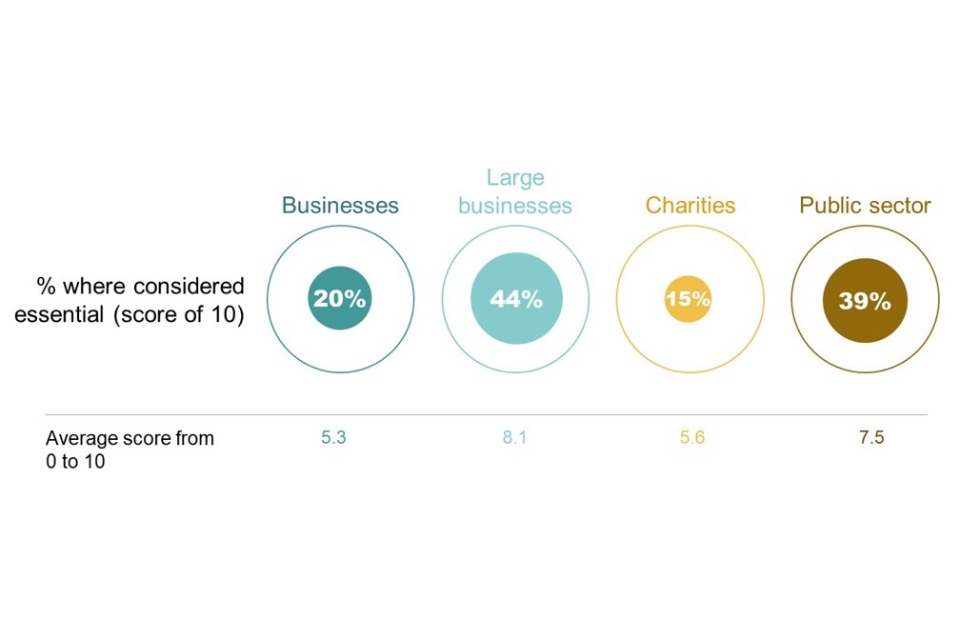

Organisations rated how important it was that their in-house cyber security teams had these skills, giving each one a score from 0 (meaning they felt it was not at all important) to 10 (meaning it was essential). As in previous years, the findings reveal that large businesses and public sector organisations are more likely to consider these skills as critical in their environment.

Observing the trend since 2020, it is noticeable that large businesses, charities and the public sector are all now much more likely to consider these skills as essential. This is particularly true in the public sector, where the proportion considering them essential has risen from fewer than one in ten (9%) in 2020 to over one in five (21%). This is one potential indicator of the increased sophistication of the cyber threat.

Figure 4.5: Perceived importance of advanced cyber security skills for those working in cyber security roles outside the cyber sector

Bases: 1060 businesses; 48 large businesses (with 250+ staff); 190 charities; 130 public sector organisations

Figure 4.6: Perceived importance of advanced cyber security skills for those working in cyber security roles outside the cyber sector (trend data)

Advanced technical skills gaps

The survey also measures businesses’ level of confidence in these advanced technical skills.

Figure 4.5 focuses on the views of businesses who judge this set of skills to be important for their organisation, and who do not outsource them but would attempt to resource them in-house if needed. These findings suggest that little has changed since 2023. Similar to 2023 there continues to be four areas where a majority of these businesses do not feel confident: forensic analysis of breaches (59%), penetration testing (55%), interpreting malicious code (53%) and security architecture or engineering (53%).

Figure 4.7: Extent to which businesses are confident in performing advanced cyber security tasks (where such tasks are identified as important for the business and not outsourced)

Bases: c.350+ businesses that do not outsource each task

Once again, we can look at the views of a broader spectrum of businesses, including those who either outsource these tasks or who do not consider them to be important for their organisation, as well as charities and public sector organisations.

In interpreting these findings, it should be noted that these are self-identified skills gaps, where the cyber security lead in an organisation admits to not feeling confident. Additionally, in calculating the prevalence of advanced skills gaps, we have assumed that those who outsource these elements of cyber security to an external provider, or who do not consider them as important for their organisation, do not have a skills gap.

The results of this analysis reveal a somewhat greater disparity between different types of organisations in the prevalence of these gaps in advanced skills, although the major gaps are the same across all organisation types – interpreting malicious code, forensic breach analysis and penetration testing. Across all these tasks, the relatively small number of charities in the sample are noticeably more likely to report a skills gap.

Figure 4.8: Percentage not confident in performing advanced cyber security tasks, by type of organisation (Base out of all organisations)

Bases: 1060 businesses; 190 charities; 130 public sector organisations.

N.B. These figures are rebased on the full survey samples, but the questions are only asked to a sub-sample of those who don’t outsource these tasks. The subsamples are very small for public sector organisations.

The percentage of charities confident in performing certain advanced tasks are mostly consistent between this and last year, however there is an increase in the number charities reporting they were not confident in carrying out vulnerability scans compared to last year (25% in 2024 vs 15% in 2023). Public sector results are also mostly consistent between 2023 and 2024, although there is a decrease in the percentage of public sector organisations who were not confident in interpreting malicious code (14% in 2024 vs. 25% in 2023). There are however more differences between results form this and last years survey for private sector organisations explored in the section below.

Extrapolating advanced technical skills gaps across the business population

This analysis of the full sample of private sector firms allows us to extrapolate to the wider population of UK businesses and to estimate the size of the skills gaps in each of these areas:

- Around 289,000 (20%) have a skills gap in forensic analysis (vs 26% last year) – a significant decrease

- Around 289,000 (20%) have a skills gap in penetration testing (vs 26% last year) – a significant decrease

- Around 260,000 (18%) have a skills gap in interpreting malicious code (vs 25% last year) – a significant decrease

- Around 260,000 (18%) have a skills gap in security architecture (vs 24% last year) – a significant decrease

- Around 231,000 (16%) have a skills gap in threat intelligence (vs 19% last year) – consistent with the previous year

- Around 202,000 (14%) have a skills gap in vulnerability scans (vs 18% last year) – a significant decrease

- Around 173,000 (12%) have a skills gap in monitoring user activity (vs 13% last year) – consistent with the previous year

A combined technical skills gap indicator

Following the same process as the basic cyber security skills gap calculation, we have merged the 7 advanced cyber security tasks referenced in Figures 4.7 and 4.8, to calculate the percentage of organisations that are not confident in carrying out at least 1 of these tasks.

27% of businesses have an advanced technical skills gap which equates to approximately 390,000 UK businesses. 35% of charities and 23% of public sector organisations also have an advanced skills gap. These results are somewhat lower than those recorded in last year’s study for businesses and public sector.

Figure 4.9: Technical skills gaps trend data

4.2 Technical skills gaps within the cyber sector

As in previous years, a survey of businesses in the cyber sector was carried out to identify areas where there might be gaps in technical skills. Once again, we found that only a minority of cyber sector employees report that their existing employees lack technical skills - 26% report that this is the case, compared to 22% in 2023. The impact of this on the ability of cyber firms to meet their business goals appears modest. 24% report that employees lacking technical skills affected their ability to meet business goals to some extent.

However, technical skills gaps among job applicants for jobs in the cyber sector are perceived to be much more prevalent – 47% report that applicants they have seen lack technical skills. This perceived skills gap – and the difficulty it presents in filling vacancies within cyber businesses – has a greater impact on their business goals. 19% report that candidates lacking technical skills affected their ability to meet their business goals to a great extent, and 28% reported that it impacted their business goals to some extent.

Over time, the size of this technical skills gap appears to have declined. In 2020, 32% of cyber businesses, looking back over the previous 12 months, reported that their employees lacked technical skills, and 59% had observed a technical skills gap among applicants.

Combining these two measures, we can estimate that 30% of cyber firms in 2024 have faced a problem with a technical skills gap (compared to 49% in 2023).

Figure 4.10 illustrates which specific types of skillsets are seen to be lacking. These are drawn from the Chartered Institute of Information Security (CIISec) Skills Framework .

While there remains a substantial overall shortfall across many different skillsets, there has been a significant decline in reported skills gaps across many areas – particularly security testing (23%, down from 35%), cyber security governance and risk management (21%, down from 31%), network monitoring and intrusion detection (16%, down from 27%) and cyber security audit and assurance (18%, down from 28%). In only one areas has there been a comparable increase in reported skills gaps since 2023 – in cryptography and communication security (24%, up from 12%).

Figure 4.10: Percentage of cyber firms that have skills gaps in the following technical areas, among those that have identified any skills gaps

Bases: 128 cyber sector businesses identifying skills gaps

4.3 Incident response skills

Perceived importance of incident response skills outside the cyber sector.

The ability to respond to cyber incidents in-house as needed is a critical part of organisations’ cyber preparedness. We have once again asked organisations to evaluate how important incident response skills are to their business, on a scale of 0 (meaning it is not at all important) to 10 (meaning it is essential). As Figure 4.11 shows, 20% of businesses regard these skills as essential. This represents a significant decrease from 2023, when 24% of businesses regarded in-house incident response skills as essential.

Large businesses (44%) and public sector organisations (39%) are more likely to feel that these skills are essential.

Figure 4.11: Perceived importance of incident response skills for those working in cyber security roles outside the cyber sector

Bases: 930 businesses; 48 large businesses (with 250+ staff); 190 charities; 130 public sector organisations

A significant proportion of businesses (38%) choose to outsource some element of their cyber security. Among those who do, incident response is an area that is very often selected to be outsourced – more than four in five (82%) of businesses do so.

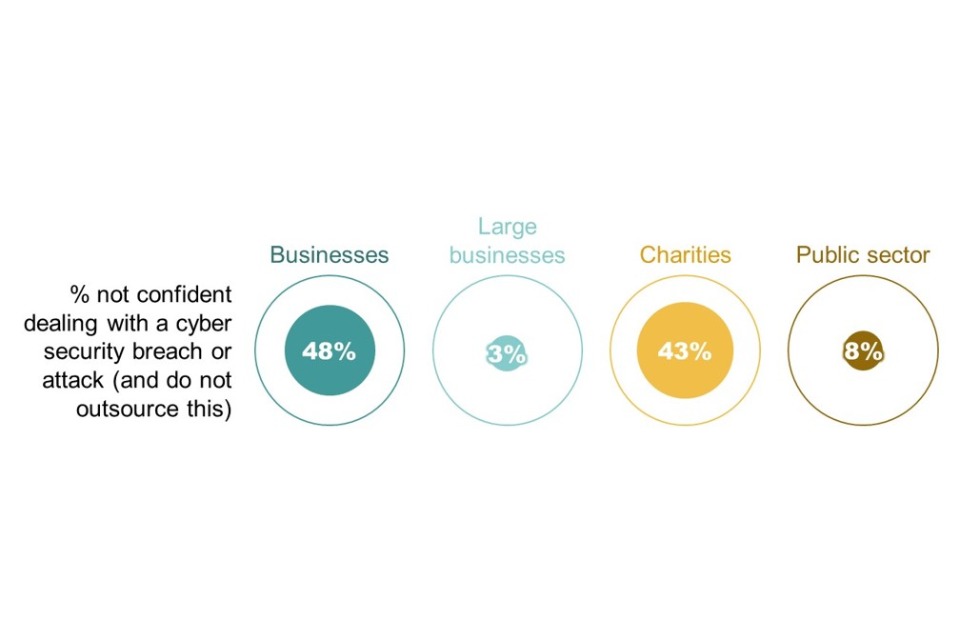

Incident response skills gap

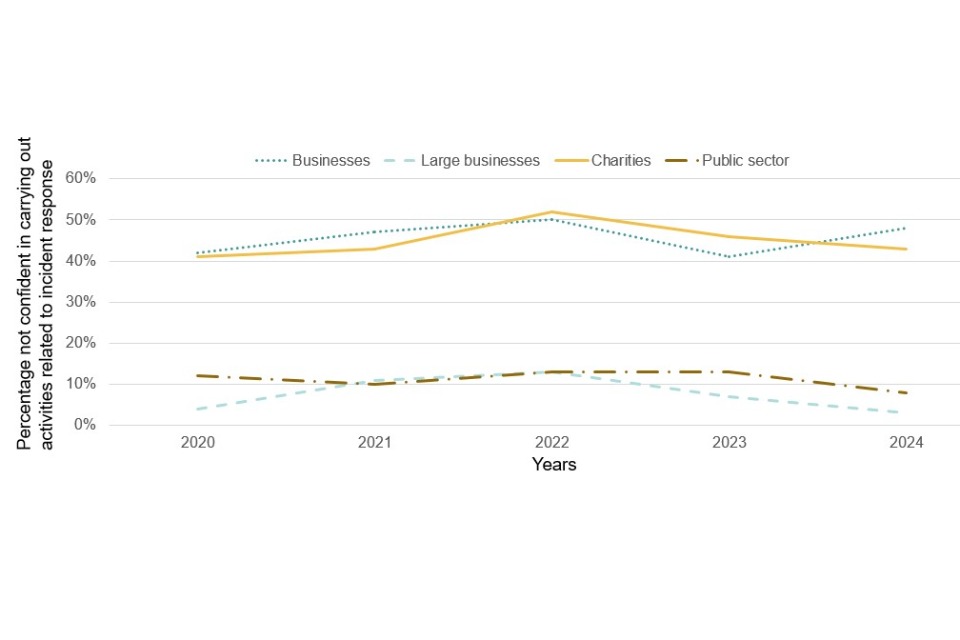

Whether or not it is outsourced, the ability to respond to an incident continues to be a major concern for organisations. As in previous years, we again find that a large proportion of businesses lack confidence in their staff’s ability to deal with an incident if it occurs. Indeed, among businesses who do not outsource incident response, this year nearly half (48%) say they are not confident in their incident response capacity, up significantly from 41% in 2023.

However, there is a growing disparity between the assessment of businesses as a whole and those of public sector organisations and larger businesses with 250+ staff. Despite widespread concern among businesses as a whole, only a small and shrinking minority of public sector bodies (8%, down from 13% in 2023) and large businesses (3%, down from 7% in 2023) now say they are not confident in their incident response capacity.

Figure 4.12: Percentage not confident in carrying out activities related to incident response

Bases: 591 businesses; 25 large businesses (with 250+ staff); 131 charities; 55 public sector organisations.

N.B. these figures are rebased on the full survey samples, but the question is only asked of a subsample. The subsamples are very small for large businesses and public sector organisations (c.25+).

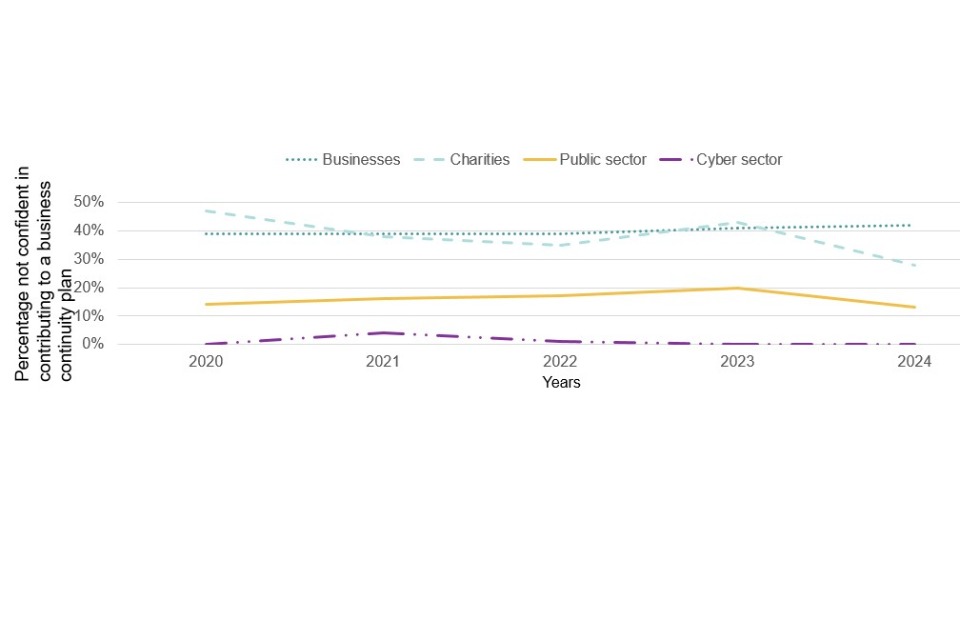

Figure 4.13: Percentage not confident in carrying out activities related to incident response

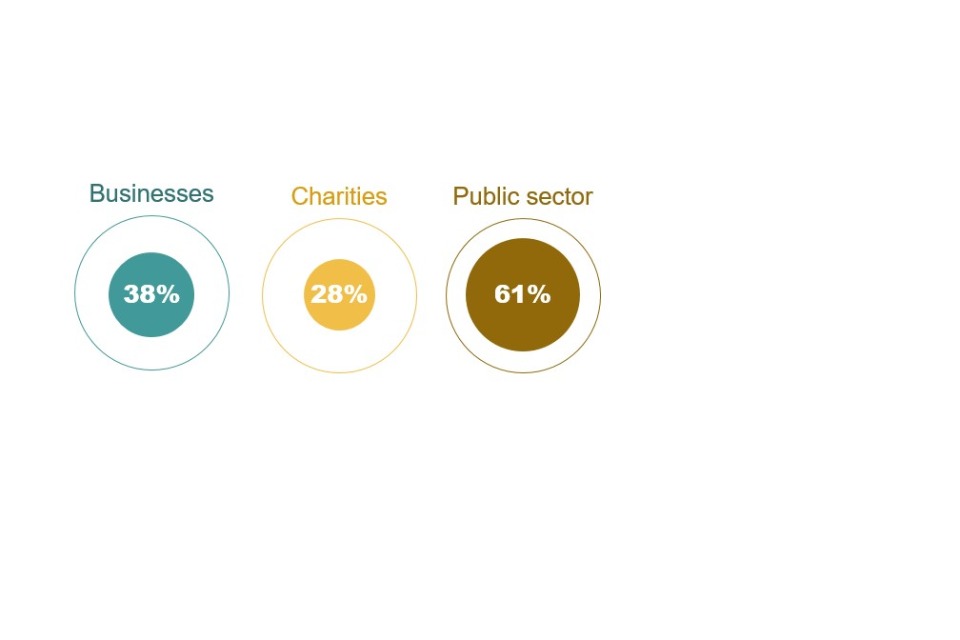

This lack of confidence in incident response among many businesses is illustrated by the concern that many of them feel about devising an incident response plan. Only 43% say they would feel confident in devising such a plan, compared to 52% who would not feel confident. The proportion who lack confidence here is similar to what we saw in 2023 (46%). Many charities feel the same way (46% confident, 47% not confident). Again, confidence in devising an incident response plan is highest among large businesses (88%) and public sector organisations (70%).

4.4 Complementary skills

The perceived importance of complementary or soft skills in the cyber sector.

Cyber sector businesses mostly appreciate the importance of complementary or ‘soft’ skills. They were again asked to rate the importance of those in cyber roles having these skills, using a scale from 0 (not at all important) to 10 (essential).

At 8.2, their average rating of the importance of these skills is similar to that given in the last three years, with 28% rating these skills as essential (10 out of 10). This level was higher, but not significantly so, in 2023 (32%).

Do cyber sector firms identify a complementary skills gap?

Once again this year, DSIT ’s Cyber Security Sectoral Analysis study, conducted using a comparable methodology to the larger survey of non-cyber organisations, provides quantitative data on cyber firms’ perceptions of gaps in complementary skills.

Despite the high level of importance they attach to soft skills, many report that their businesses are lacking in this area. Just over one in three (34%) report that their firms have a complementary skills gap, consistent with 2023 (43%) Only 4% of cyber firms say this has impacted their ability to meet their business goals to a great extent. As we discuss in Section 6.2, candidates with both complementary and technical skills are in particular demand among employers.