- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

The Stunning Survival Story of Ernest Shackleton and His Endurance Crew

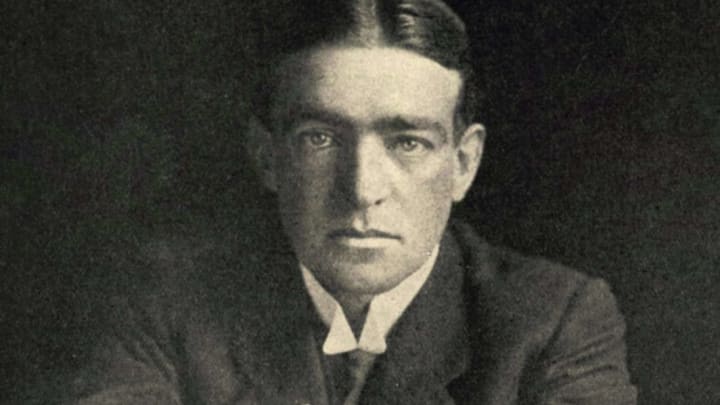

By: Kieran Mulvaney

Updated: May 2, 2024 | Original: October 21, 2020

All year, the ship had been trapped, ice pushing and pinching the hull, the wood howling in protest. Finally, on October 27, 1915, a new wave of pressure rippled across the ice, lifting the ship’s stern and tearing off its rudder and its keel. Freezing water began to rush in.

“She’s going, boys,” came the cry. “It’s time to get off.”

From the moment Ernest Shackleton and his crew aboard the British expedition ship, HMS Endurance had become immobilized in Antarctica's ice 10 months earlier, they had been preparing for this moment. Now, those on board removed their last remaining belongings from the ship and set up camp on the ice. Twenty-five days later, what remained of the wreck convulsed once more, and the Endurance disappeared beneath the ice.

Incredibly, all 27 men under Shackleton's command would survive the grueling Antarctic expedition, but their ship remained sunk and lost to history—until 106 years later.

On March 9, 2022, a team of scientists and adventurers announced they had finally located what remained of the Endurance at the bottom of Antarctica's Weddell Sea. The team made the discovery using submersibles and undersea drones and released stunning photos of the long-lost wooden ship where it had lodged in the seabed nearly 10,000 feet deep in clear and icy waters.

Endurance Is Locked in by Ice

Endurance had left South Georgia for Antarctica on December 5, 1914, carrying 27 men (plus one stowaway, who became the ship’s steward), 69 dogs, and a tomcat erroneously dubbed Mrs. Chippy. The goal of expedition leader Shackleton, who had twice fallen short—once agonizingly so—of reaching the South Pole, was to establish a base on Antarctica’s Weddell Sea coast.

From there a small party, including himself, would set out on the first crossing of the continent, ultimately arriving at the Ross Sea, south of New Zealand, where another group would be waiting for them, having laid depots of food and fuel along the way.

Two days after leaving South Georgia, Endurance entered the pack ice—the barrier of thick sea ice that stands guard around the Antarctic continent. For several weeks, the ship poked and prodded its way through leads in the ice, gingerly making its way south; but on January 18, a northerly gale pressed the pack hard against the land and pushed the floes tight against each other. Suddenly, there was no way forward, nor any way back. Endurance was beset—in the words of one of the crew, Thomas Orde-Lees, “frozen like an almond in the middle of a chocolate bar.”

They had been within a day’s sailing of their landing place; now the drift of the ice was slowly pushing them farther away with each passing day. There was nothing else to do but to establish a routine and wait out the winter.

Shackleton wrote Alexander Macklin, one of the ship’s surgeons, “did not rage at all, or show outwardly the slightest sign of disappointment; he told us simply and calmly that we must winter in the Pack; explained its dangers and possibilities; never lost his optimism and prepared for winter.”

In private, however, he revealed greater foreboding, quietly expressing to the ship’s captain, Frank Worsley, one winter’s night that, “The ship can’t live in this, Skipper … It may be a few months, and it may be only a question of weeks or even days … but what the ice gets, the ice keeps.”

Survival on an Ice Floe

In the time that passed between abandoning Endurance and watching the ice swallow it up completely, the crew salvaged as many provisions as they could, while sacrificing anything and everything that added weight or would consume valuable resources— including bibles, books, clothing, tools and keepsakes. Some of the younger dogs, too small to pull their weight, were shot, as was, to the chagrin of many, the unfortunate Mrs. Chippy.

The initial plan was to march across the ice toward land, but that was abandoned after the men managed just seven and a half miles in seven days. “There was no alternative,” wrote Shackleton, “but to camp once more on the floe and to possess our souls with what patience we could till conditions should appear more favorable for a renewal of the attempt to escape.” Slowly and steadily, the ice drifted farther to the north; and, on April 7, 1916, the snow-capped peaks of Clarence and Elephant Islands came into view, flooding them with hope.

“The floe has been a good friend to us,” wrote Shackleton in his diary, “but it is reaching the end of its journey, and is liable at any time now to break up.”

On April 9, it did just that, splitting beneath them with an almighty crack. Shackleton gave the order to break camp and launch the boats, and all at once, they were finally free of the ice that had alternately bedeviled and supported them.

Now they had a new foe to contend with: the open ocean. It threw freezing spray in their faces and tossed frigid water over them, and it batted the boats from side to side and brought brave men to the fetal position as they battled the elements and seasickness.

Through it all, Captain Worsley navigated through the spray and the squalls, until after six days at sea, Clarence and Elephant Islands appeared just 30 miles ahead. The men were exhausted. Worsley had by that stage not slept for 80 hours. And while some were crippled by seasickness, others were wracked with dysentery. Frank Wild, Shackleton’s second-in-command, wrote that “at least half the party were insane.” Yet they rowed resolutely toward their goal, and on April 15, they clambered ashore on Elephant Island.

Marooned on Elephant Island

It was the first time they had been on dry land since leaving South Georgia 497 days previously. But their ordeal was far from over. The likelihood of anybody coming across them was vanishingly small, and so after nine days of recuperation and preparation, Shackleton, Worsley and four others set out in one of the lifeboats, the James Caird, to seek help from a whaling station on South Georgia, more than 800 miles away.

For 16 days, they battled monstrous swells and angry winds, baling water out of the boat and beating ice off the sails. “The boat tossed interminably on the big waves under grey, threatening skies,” recorded Shackleton. “Every surge of the sea was an enemy to be watched and circumvented.” Even as they were within touching distance of their goal, the elements hurled their worst at them: “The wind simply shrieked as it tore the tops off the waves,” Shackleton wrote. “Down into valleys, up to tossing heights, straining until her seams opened, swung our little boat.”

The next day, the wind eased off and they made it ashore. Help was almost at hand; but this, too, was not the end. The storms had pushed the James Caird off course, and they had landed on the other side of the island from the whaling station. And so Shackleton, Worsley and Tom Crean set off to reach it by foot—climbing over mountains and sliding down glaciers, forging a path that no human being had ever forged before, until, after 36 hours of desperate hiking, they staggered into the station at Stromness.

'My Name Is Shackleton'

There was no conceivable circumstance under which three strangers could possibly appear from nowhere at the whaling station, and certainly not from the direction of the mountains. And yet here they were: their hair and beards stringy and matted, their faces blackened with soot from blubber stoves and creased from nearly two years of stress and privation.

And old Norwegian whaler recorded the scene when the three men stood before the station manager Thoralf Sørlle:

“Manager say: ‘Who the hell are you?’ And the terrible bearded man in the center of the three say very quietly: ‘My name is Shackleton.’ Me – I turn away and weep.”

Rescue Mission to Elephant Island

Once the other three members of the James Caird had been retrieved, attention turned to rescuing the 22 men remaining on Elephant Island. Yet, after all that had gone before, this final task in many ways proved to be the most trying and time-consuming of all. The first ship on which Shackleton set out ran dangerously low on fuel while trying to navigate the pack ice, and was forced to turn back to the Falkland Islands. The government of Uruguay proffered a vessel that came within 100 miles of Elephant Island before being beaten back by the ice.

Each morning on Elephant Island, Frank Wild, whom Shackleton had left in charge, issued the call for everyone to “Lash up and stow” their belongings. “The Boss may come today!” he declared daily. His companions grew increasingly dispirited and doubtful. “Eagerly on the lookout for the relief ship,” recorded Macklin on August 16, 1916. “Some of the party have quite given up hope of her coming.” Orde-Lees was clearly one of them. “There is no good in deceiving ourselves any longer,” he wrote.

But Shackleton procured a third ship, the Yelcho, from Chile; and finally, on August 30, 1916, the saga of the Endurance and its crew came to an end. The men on the island were settling down to a lunch of boiled seal’s backbone when they spied the Yelcho just off the coast. It had been 128 days since the James Caird had left; within an hour of the Yelcho appearing, all ashore had broken camp and left Elephant Island behind. Twenty months after setting out for the Antarctic, every one of the Endurance crew was alive and safe.

While Shackleton's crew miraculously made it back to England, his ship did not. For more than a century, the Endurance remained among history's most elusive shipwrecks. But in 2022, an international team of marine archaeologists, explorers and scientists located the Endurance at the bottom of the Weddell Sea, approximately four miles south of the position originally recorded when Endurance sank.

“We have made polar history with the discovery of Endurance, and successfully completed the world’s most challenging shipwreck search,” said John Shears , the leader of Endurance22, the expedition team that used submersibles and drones to locate the wooden ship.

Photos released from the Endurance22 expedition revealed the sunken, three-masted ship in mesmerizing detail, including an image of its stern where its name "ENDURANCE" was visible above a five-pointed star.

Shackleton's Early Death

Ernest Shackleton never did reach the South Pole or crossed Antarctica. He launched one more expedition to the Antarctic, but the Endurance veterans who rejoined him noticed he appeared weaker, more diffident, drained of the spirit that had kept them alive. On January 5, 1922, with the ship at South Georgia, he had a heart attack in his bunk and died. He was just 47.

With his death, Wild took the ship to Antarctica; but it proved unequal to the task, and after a month spent futilely attempting to penetrate the pack, he set a course for Elephant Island. From the safety of the deck, he and his comrades peered through binoculars at the beach where so many of them had lived in fear and hope.

“Once more I see the old faces & hear the old voices—old friends scattered everywhere,” wrote Macklin. “But to express all I feel is impossible.”

And with that, they turned north one last time and went home.

Alexander, Caroline, The Endurance: Shackleton’s Legendary Antarctic Expedition ( Alfred A. Knopf , 1998) Heacox, Kim, Shackleton: The Antarctic Challenge ( National Geographic Society, 1999) Huntford, Roland, Shackleton ( Hodder & Stoughton, 1985) Lansing, Alfred, Endurance: Shackleton’s Incredible Voyage ( Perseus Books , 1986) Shackleton, Ernest, South ( Macmillan , 1920) Worsley, F.A., Shackleton’s Boat Journey ( Hodder & Stoughton, 1940)

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Endurance Expedition: Shackleton's Antarctic survival story

The Endurance Expedition was a failed mission to cross the Antarctic on foot, leaving 28 explorers stranded.

Endurance Expedition

Shackleton's rescue mission, fate of the second crew, shackleton's earlier expeditions, additional reading, bibliography.

The Endurance Expedition was a British mission to cross the Antarctic on foot in 1914-17. Launched in August 1914, the expedition became one of the most famous survival stories of all time after the expedition's ship, Endurance, became stranded and then sank during the voyage to the Antarctic.

The Endurance's crew became stranded on the remote Elephant Island and were only rescued over four months later, in August 1916, after expedition leader Sir Ernest Shackleton (1874-1922) left to seek help. The miraculous survival of the Endurance expedition crew earned Shackleton worldwide fame though his goal to cross the Antarctic on foot was never achieved.

The location of the sunken ship Endurance was lost for 107 years until being rediscovered on March 5, 2022.

Formally known as the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, the Endurance Expedition to Antarctica began in August 1914. The crew sailed to the Weddell Sea via South Georgia. "His expedition would consist of two ships: one would drop supply depots for him and the other from the other side of the continent, which he would personally lead," British explorer and Shackleton biographer Sir Ranulph Fiennes told All About History magazine. "He hoped to cross Antarctica and make a famous name for himself over and above Scott." On the other side of the continent, the second crew, called the Ross Sea Party, planned to drop off depot supplies from their ship Aurora. With a crew of 28 (including Shackleton), Endurance entered the Weddell Sea but became trapped in pack ice during Dec. 1914. Stuck fast in the ice, with the crew unable to break Endurance free, the ship drifted to within approximately 30 miles (48km) of Antarctica in January 1915, before drifting north.

Endurance was slowly crushed by the moving ice, until Shackleton ordered the crew to abandon ship on Oct. 27, 1915. The ship sank shortly afterwards and the crew escaped with three lifeboats and limited supplies. Shackleton led his men through the shrinking ice pack for months while they tried to reach land.

On April 9 1916, the Endurance Expedition crew left the ice floe in the lifeboats, reaching the uninhabited and remote Elephant Island on April 14. Ten days later, Shackleton set off to find help. He selected five crew members to join him and set sail in the 22.5-foot-long (6.9-meter-long) lifeboat called the "James Caird". He left the remainder of his men in the care of his second-in-command Frank Wild, who upturned the two remaining lifeboats to use as shelter.

Related: When did Antarctica become a continent?

Shackleton and his small crew sailed over 800 miles (1,300 km) across the Southern Ocean to a group of whaling stations in South Georgia. The audacious rescue mission later became known as the Caird voyage after their small lifeboat. "It was the most amazing suffering over a long period. There were constant rebuffs and to be wet and cold is utterly debilitating," Fiennes said. "How none of them went completely mad over that period of floating is just incredible. I have never experienced hot or cold suffering that reminded me in an even miniscule way of Shackleton’s Caird voyage."

Shackleton and his men endured heavy seas, Force-9 winds and ice build-ups on the hull that threatened to capsize their vessel. Shackleton later recounted that the waves reached heights of over 100 feet (30 meters) and moved at speeds of 50 mph (80kmph). On May 5, 1916, the boat was even struck by a tidal wave that Shackleton initially mistook for the sky. He later wrote: "I have never seen a wave so gigantic."

The James Caird somehow survived the voyage, which Fiennes credits to Shackleton’s leadership. "They had already experienced Endurance sinking and lived on ice floes for months before trying to work out the safest way out. Whatever way Shackleton chose, death was the likely outcome but he kept cheerful."

After 17 days at sea, the James Caird landed on the southern coast of South Georgia — the opposite side of the island from their destination. After recovering from the voyage, Shackleton and two of his crew trekked for 36 hours across the island, reaching Stromness station on May 20. Shackleton next arranged a rescue ship to collect the remaining 22 crew stranded on Elephant Island.

After several aborted rescue attempts, Shackleton was lent a tugboat called Yelcho by the Chilean government and he finally reached Elephant Island on August 30, 1916. A smoke signal was sent from the shore while Shackleton approached the beach in a small boat. Figures emerged from the capsized lifeboats and when he was within earshot Shackleton called out: "Are you alright?"

“All well!” Came the reply. All the men on the island had survived. "It is an absolutely incredible survival story,” Fiennes said.

The story of the Endurance's crew is a supreme example of survival against the odds. However, the neglected Ross Sea Party became stranded off Antarctica until January 1917. "Shackleton was criminally negligent in his planning for the other side," Fiennes said. "Three of the party (including the commander Aeneas Mackintosh) died and of course there was no way of knowing that the Endurance had sunk. The three men died horribly for nothing. They had actually managed to drop most of the food off, even though their ship with most of their kit had been caught in the ice and taken away before they had unloaded properly. It was a disaster.”

Because the story of Endurance has become so famous, the sufferings of the Ross Sea Party and the fact that Shackleton achieved none of his actual objectives during 1914-17 have almost been forgotten.

It wasn’t until Sir Vivian Fuchs’s Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1955-58 that the first overland crossing of Antarctica was completed. Fuchs achieved this by using tracked snow vehicles and it wasn’t until Fiennes’ own mission, named the Unsupported Antarctic Continent Expedition (1992-93) that a crossing of Antarctica by foot was successful.

In 1901 Shackleton served as Third Officer under the command of Captain Robert Falcon Scott on the British National Antarctic Expedition, named after the expedition's ship 'Discovery'. The expedition was a milestone in British polar exploration, and the group conducted extensive scientific and geographical research into what was then a largely unexplored continent.

The Discovery Expedition also included an early attempt to reach the South Pole. Shackleton accompanied Scott and Dr Edward Wilson on this journey and they reached a ‘Farthest South’ record of 420 miles from the Pole on Dec. 30 1902.

During the attempt to reach the South Pole, Shackleton suffered from ill health, though this did not stop him continuing with the journey. “Shackleton did show an incredible willpower and it had to be greater than anybody else because of his illnesses," said Fiennes. "He had a weak heart and knew it so he wouldn’t allow anyone to test it. He also had lung problems, which were exacerbated by altitude… On all of his expeditions most people would have withdrawn with that state of health.”

In 1907, Shackleton returned to the Antarctic but this time he was in command of what was known as the ‘Nimrod’ Expedition. Along with fellow explorers Jameson Adams, Eric Marshall and Frank Wild he achieved the record for reaching the furthest south, in his attempts to once again reach the South Pole. "Shackleton got much further south by finding an inlet at Mount Hope to get to the Beardmore Glacier," Fiennes said. "He then got to within 97 miles of the South Pole, which was amazing. This was a world record and I would call it a success on the way to the ultimate success. It wasn’t a failure but Shackleton realised that his critics would deem him a failure because he hadn’t quite reached the Pole."

As well as reaching the farthest south, a separate group from the expedition reached the estimated location of the South Magnetic Pole. The expedition also achieved the first ascent of Antarctica’s second-highest volcano, Mount Erebus, and Shackleton was knighted by Queen Victoria upon his return.

Historian Dan Snow spoke to Ranulph Fiennes about his research into Shackleton's expedition and his own Antarctic exploring. The Royal Geographical Society has a wealth of fantastic home-schooling, classroom or personal study resources on Shackleton's Antarctic expeditions.

- " Shackleton: A Biography " Ranulph Fiennes (Michael Joseph, Penguin Random House, 2021)

- Alfred Lansing, Endurance. The true story of Shackleton’s incredible voyage to the Antarctic (Phoenix, 2003)

- Shackleton Endurance Expedition - Timeline, Royal Geographic Society

- Ranulph Fiennes' expeditions and challenges , Marie Curie

- Navigation of the James Caird on the Shackleton Expedition , Records of the Canterbury Museum, 2018 Vol. 32: 23–66 Canterbury Museum 2018

- THE ANTARCTIC PHOTOGRAPHS OF FRANK HURLEY, HERBERT PONTING AND CAPTAIN SCOTT

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tom Garner is the Features Editor for History of War magazine and also writes for sister publication All About History . He has a Master's degree in Medieval Studies from King's College London and has also worked in the British heritage industry for the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust , as well as for English Heritage and the National Trust . He specializes in Medieval History and interviewing veterans and survivors of conflicts from the Second World War onwards.

- Timothy Williamson Editor-in-Chief, All About History

Blood Falls: Antarctica's crimson waterfall forged from an ancient hidden heart

Antarctic ice hole the size of Switzerland keeps cracking open. Now scientists finally know why.

Earth from space: Mysterious, slow-spinning cloud 'cyclone' hugs the Iberian coast

Most Popular

- 2 Rare fungal STI spotted in US for the 1st time

- 3 James Webb telescope finds carbon at the dawn of the universe, challenging our understanding of when life could have emerged

- 4 Earth's upper atmosphere could hold a missing piece of the universe, new study hints

- 5 Why did Homo sapiens emerge in Africa?

- 2 32 haunting shipwrecks from the ancient world

- 3 Neanderthals and humans interbred 47,000 years ago for nearly 7,000 years, research suggests

- 4 Bear vs tiger: Watch 2 of nature's heavyweights face off in the wild in India

- 5 Bornean clouded leopard family filmed in wild for 1st time ever

The most comprehensive and authoritative history site on the Internet.

Ernest Shackleton’s Polar Dreams, Polar Disappointments

The following account describes Sir Ernest Shackleton’s expedition to the Antarctic in 1907-09, which followed Captain Robert F. Scott’s earlier (1902-03) attempt to reach the geographic Pole. This year marks the 90th anniversary of the Shackleton expedition.

Just as the race to explore space captured people’s imaginations in the latter part of this century, the quest to conquer the frozen and mysterious lands of the Arctic and Antarctic consumed explorers during the first part. Those who ventured into the vastness of the Polar regions were the popular heroes of the day. Like today’s astronauts—or athletes—they commanded awe and respect. The Antarctic was Earth’s final frontier. Certainly the race for the South Pole was as dramatic and competitive as any race has been.

Ernest Shackleton wanted to be part of something that would bring honour to the British Empire. His interest in the South Pole began at age 16 when he left school to ship out to sea, much to his father’s annoyance. By 24, he was certified to command a ship anywhere on the seven seas. The romance of the sea and the adventure led him to volunteer for Scott’s 1902 National Antarctic Expedition, during which he served as Third Mate.

On that first voyage to the Antarctic, a rift between the Royal Navy officers, including Captain Scott, and Merchant Navy volunteers, such as Shackleton, led to dissension over the chain of command and over the mission’s goals. Shackleton, in particular, disliked formality. Whether whaling seamen or Royal Navy captains, all were men of the sea to him. Stripes—or the lack of them—made no difference.

Despite the personality and rank differences, Scott selected Shackleton to take part in the trek towards the Pole. Shackleton would always be grateful to him for that, considering the men from whom he had to choose. The third member of the team was Dr. Edward A. Wilson, who became Shackleton’s great friend.

The team members encountered numerous problems on that expedition with dogs, transport, diet, and weather. None of them knew how to use dogs and sledges. Physically, all of them had problems, which Wilson diagnosed as scurvy. They did not have the proper type of food to prevent this scourge, and, in the end, they did not bring enough to go around. Blizzards and whiteouts hampered their movement, and eventually they had to abandon their goal of reaching the Pole.

At the same time, this foray yielded many positive results. They all reached 82 degrees, 15 minutes South. Scott and Wilson went on one mile further on 30th December, reaching the “furthest South,” while Shackleton stayed behind, as he was too ill to proceed.

Ultimately, Wilson and Shackleton pressured Scott into abandoning the trek to the Pole. He seemed bent on carrying on, but the Pole was still far off, the three men had already eaten most of their food, and fatigue had taken a heavy toll on their strength. In addition, Shackleton developed scurvy. Had Shackleton not become ill, Scott might not have agreed to return as he did. As it was, they rushed from depot to depot. As ill as Shackleton apparently was, he still assisted with the sledging, although at one point he had to be carried briefly on the sledge. Afterwards, he claimed that he was never as ill as Scott made it appear in his account, The Voyage of the “Discovery.” On 3rd February, 1903, they returned to the ship, just over three months and 960 miles after they began the journey.

Scott then sent Shackleton home, ostensibly to recover from his illness, but Scott may simply have wanted to rid himself of a rival. Shackleton arrived in London on 12th June, 1903. After stints as a journalist, secretary to the Royal Scottish Geographical Society, and an unsuccessful bid for a seat in Parliament, he announced plans for another Antarctic expedition in the March 1907 Geographical Journal. His objectives included geographical exploration and an attempt on the Pole, as well as collecting meteorological, geological, and biological data. But this second voyage also grew out of a personal need to prove to himself–and to sceptics–that he was capable of leading and completing an expedition.

He tackled the time-consuming and difficult tasks of acquiring financing, selecting a crew and ship, and arranging for stores. Thanks to the generosity of many who believed in his work, he soon felt ready to better Scott’s record, and he next set his thoughts to selecting the companions who would accompany him on the shore party.

Shackleton’s first choice, his chum from the Discovery, “Billy” Wilson, declined Shackleton’s invitation. Wilson later perished along with Scott while returning from the famous Terra Nova Antarctic expedition of 1912. Nevertheless, Shackleton assembled a first-rate shore party for the “British Antarctic Expedition, 1907”: Lieutenant James A. Boyd, R.N.R.; Sir Philip Lee Brocklehurst, assistant geologist; Bernard Day, motor mechanic; Ernest Joyce, in charge of the dogs; Alistair Forbes Mackay, second surgeon; Eric Marshall, chief surgeon, photographer, and cartographer; George Marston, artist; James Murray, biologist; Raymond Priestley, geologist and photographer; William Roberts, cook; and Frank Wild, in charge of provisions.

More on shackleton

- Shackleton’s Storied ‘Endurance’ Found After 107 Years

- ‘South: The Endurance Expedition’: A Battle Between Man and the Elements

The ship Shackleton had originally set his sights on proved financially out of the question; he had to settle for an older vessel, the Nimrod. He considered his vessel’s name, taken from a mighty hunter described in the biblical book of Genesis, to be a good omen. Once again, though, he had to make do with second best after his first choice for captain of the Nimrod did not accept his offer. If he had been superstitious, he might have heeded these signs. But, as Shackleton had already contracted for a dozen Manchurian ponies, dogs, sledges, and a pre-fabricated hut, and a benefactor had arranged a specially-built motor car, an Arroll-Johnston—he determined to proceed.

With the benefit of hindsight, many people today look back with amazement on the team’s dependence on the motor car and Manchurian ponies. In fact, Shackleton spent time in Norway before the expedition, consulting two of the most illustrious Polar explorers, Fridtjof Nansen and Otto Sverdrup, who advised Shackleton against using these modes of transportation. In the end, however, he rejected this expert advice. The car, he reasoned, had been specially prepared for Antarctic conditions. And the ponies, Shackleton believed, could haul far more sledge weight than dogs. At the very least, he knew that his team could man-haul the sledges if necessary.

If Shackleton lacked good judgement in his choice of transportation, he made better decisions when it came to shelter. The expedition’s hut, prepared by a firm in Knightsbridge, was prefabricated for ease of assembly, rather than transported whole, as Scott’s had been. Scott’s cumbersome hut had taken up precious cargo space on Discovery. Constructed of fir, Shackleton’s hut was insulated with felt and shredded cork. This habitat of 33 x 19 feet would have to house 15 men in close proximity for many months.

With great anticipation, Shackleton and his men set sail from London for Torquay in the south-west of England on 7th August, 1907. On their way, they received a command to meet King Edward VII, Queen Alexandra, and other members of the Royal Family at Cowes. His Majesty conferred the Commander of the Victorian Order on Shackleton, as he had on Scott some five years earlier. Her Majesty handed Shackleton a Union Jack to place at the Pole. Later at Torquay, he bade farewell to his wife, Emily, his children, and his brother, Frank, a ne’er-do-well, who had recently been linked to the theft of the Irish crown jewels.

Shackleton took care of other business, rejoining Nimrod in Lyttleton, New Zealand. Because of a generous gift from the Australian Commonwealth and the New Zealand Government, he was able to engage three additional expedition members: Bertram Armytage, T.W. Edgeworth David, and Douglas Mawson. They set sail again on New Year’s Day, 1908.

The ship Koonya towed them south to the Ice Barrier, allowing them to save coal they would badly need during their tenure in the Antarctic. They headed south through rough seas for some two weeks, dodging icebergs before passing through the Ross Sea ice into open water.

Shackleton’s original plan had been to establish a base camp in King Edward VII Land, but due to the sea ice conditions, the team couldn’t reach it. Also, the topography at the Bay of Whales had changed, so he decided not to chance a landing. Nimrod had only a short while before it would become frozen in the ice, and Captain England was nervous that his ship would become stuck fast before Shackleton found a place to land his stores, animals, motor car, and shore party.

After wrestling with his conscience, Shackleton made a controversial decision to revoke an agreement he had made with Scott in order to keep his men alive. Prior to Shackleton’s departure, Captain Scott wrote and strongly suggested that Shackleton not use his 1902 Hut Point base or venture into McMurdo Sound, which Scott deemed “his territory.” At the time Shackleton received this “suggestion,” he had no thought of landing there, so he agreed to Scott’s request.

[In an interview last year Shackleton’s granddaughter, The Honourable Alexandra Shackleton, asserted, “Scott should never have asked Grandfather to make such a commitment; and Grandfather should never have given it. Scott considered it a personal betrayal and never forgave Grandfather. The absolutes were different then; it was life or death. The Establishment considered it a most dishonourable action, but it should have been understood that he had no choice.”]

Shackleton’s team finally offloaded near Cape Royds, about 20 miles north of Hut Point. It took them about 15 days to turn their hut into cramped but liveable quarters. In order to make the best use of their small living space, they arranged the dining table so it could be pulled up to the ceiling. The men settled into a routine, trying not to get on each other’s nerves.

Paired off, they moved into their 6 x 7-foot cubicles, which had names reflecting the occupants: “Rogues’ Retreat” was Joyce and Wild’s; “The Pawn Shop” reflected David and Mawson’s untidy habits; Adams and Marshall’s quarters were dubbed “No. 1 Park Lane.”

Wild and Joyce, having had a crash course in printing in London, set about printing the first book published in the Antarctic, Aurora Australis [the Southern Lights], with etchings by Marston. They had to keep a candle burning under the inking plate to prevent it from freezing.

A number of the expedition members captured historic moments on film. Shackleton later used these to prove how much they had accomplished, despite the fact that they did not reach the South Pole. Many of the photographs were reproduced in his book on the expedition, The Heart of the Antarctic.

They hoped to achieve several things that spring. First, the quartet of Adams, Marshall, Wild, and Shackleton would attempt to reach the South Geographic Pole, a 1,708-mile journey, with ponies pulling sledges. David, Mawson, and Mackay would trek to the South Magnetic Pole, a journey of some 1,200 miles. David’s party used the motorcar to relay supplies to two depots, but it became mired in the soft snow of McMurdo Sound and soon was of no use.

Prior to the trek to the Poles, Shackleton assigned Adams, Brocklehurst, David, Mackay, Mawson, and Marshall to undertake the ascent of the volcano, Mount Erebus. All, except Brocklehurst, reached the summit on 10th March, 1908. Getting there had been a tremendous physical struggle. Having no mountaineering gear, as there had been no plan to attempt the climb, they man-hauled all their provisions to the 13,000-foot peak and were the first to ever look into the jaws of the volcano. Through extraordinary resourcefulness, courage, and dedication, the team achieved a triumph.

To the south pole

The team of Shackleton, Jameson Boyd Adams, Eric Marshall, and Frank Wild struck out for the Pole on 29th October, 1908. Even while travelling through the harshest environment on earth, they maintained a semblance of civilization, taking along reading material (including Shakespeare and Dickens), jam and cocoa, and especially tobacco.

The Polar party experienced difficulties with their ponies and the weather right from the outset. The explorers had planned to use the ponies to haul supplies, as well as for meat, but the animals had difficulty walking in deep snow, often sinking up to their bellies. In a strange role reversal, the explorers found themselves having to carry their own provisions as well as fodder for the ponies. As if that were not enough, the ponies became snow blind. The death of all but four of them from eating volcanic sand, while distressing to Shackleton, may have been a blessing in disguise.

The white landscape affected the explorers as well as the ponies. At times they couldn’t distinguish the horizon; the sky and the ice melded into one. The temperature dropped to 52 degrees Fahrenheit. But despite the harsh conditions and unexpected setbacks, the party surpassed Scott’s “Furthest South” almost a month after setting out.

By 1st December, 1908, only one pony, Socks, remained. Then a week later, he disappeared down a crevasse, almost taking Wild with him. The unexpected loss deprived the expedition of a source of meat but freed up the supply of pony fodder, which became part of the team’s daily ration.

The four explorers plodded on, hauling 1,000 pounds through forbidding terrain on below-minimum rations. To lessen the danger of falling through crevasses, they roped themselves together. By 9th December, they were measuring their progress not in miles but yards.

It was gruelling, arduous labour. Because they could not transport all their supplies at once, the party had to constantly backtrack to retrieve what had been left behind, so that every advance of six miles required 18 miles of walking. In his journal, Shackleton described each passing day as “the most difficult we had endured.”

While Shackleton’s team headed for the South Geographic Pole, another party set out for the Magnetic Pole. On 16th January, 1909, this second team reached their goal. They recorded their achievement by taking a photograph of themselves standing by the Union Jack they brought with them. The same day they trudged 24 miles back to their supply depot to rest and then began their journey back to meet their ship, Nimrod.

Midsummer’s Day, 21st December, found Shackleton’s team frost-bitten and hungry. Condensation from their breath froze on their beards, then melted and seeped under their shirts, only to freeze again inside their clothes.

After an 11-hour march on Christmas Day, they rewarded themselves with a splendid Christmas dinner. According to Shackleton’s notes, they feasted on Oxo and pemmican (dried meat pounded into paste with fat and made into patties) boiled with some of the pony food, and plum pudding with a splash of liqueur. The meal ended with a much-welcomed cigar.

As the year’s end approached, wind and snow, less-than-adequate provisions, and the effects of altitude were taking their toll on the explorers. Their body temperatures had dropped to about 94 degrees–not a good indication of their physical state. Although Shackleton resisted the temptation to admit defeat, after 1st January, 1909, he began to realize that he might not achieve his objective. Their food simply would not last long enough.

The expedition leader decided that 6th January would be their last day out. Despite soft snow and biting cold, they advanced another 13 miles. Then, for the next two days a raging blizzard kept them in their tents.

When the storm broke on 9th January, Shackleton reversed his earlier decision and dashed south once more, reaching 88 degrees, 23 minutes south longitude, 162 degrees east latitude. They had gone farther south than anyone ever had, stopping just 97 nautical miles from the Pole. There the party planted the Union Jack and the Queen’s flag, and Marshall photographed the scene. Then, reluctantly, they headed home, a decision Shackleton called the most difficult he ever made. “Whatever regrets may be, we have done our best,” he wrote in his diary.

Even after turning back toward Cape Royds, the Polar party faced great danger. They had eaten most of their food and exhausted much of their energy, and time and the season were running out. However, the wind blew at their backs, helping the team to make runs of 15 to 20 miles for several days.

Food remained their greatest worry. Shackleton continually reduced the daily ration of biscuits, cocoa, and tea. In late January, the party marched for 20 hours with little food and even less rest. With 300 miles to go, they had very nearly reached the limits of their energy. The food ran out on 26th January, and Marshall went on alone to the next depot to bring back pony meat. Shortly thereafter, they all came down with dysentery, which Marshall attributed to bad meat.

Throughout the return trip, the explorers battled difficult terrain, incredible cold, and lack of food. Then the unusually fine weather turned bad and a blizzard struck. By Shackleton’s 35th birthday, on 15th February, they reached another supply depot. To keep up spirits, they imagined the culinary delights awaiting them upon homecoming.

By now, time was running as short as food. Before setting out on his journey, Shackleton had left orders for Nimrod to sail on 1st March, whether the Polar party had returned or not. Now, after trudging and sledging for 126 days and for more than 1,700 miles, it looked as if Shackleton might not be able to meet that deadline.

To quicken his pace, Shackleton left Marshall, who had become very ill, in Adams’ care and set off with Wild and one day’s provisions for the final dash to Hut Point. They arrived to find no ship, just a message indicating that all the other parties had returned safely. Shackleton and Wild spent a sleepless, cold, and anxious night in the hut. Unexpectedly, Nimrod reappeared the next morning, intending to land a rescue party or at least recover the bodies of the missing explorers.

As soon as he had satisfied his hunger, Shackleton set out with a relief party to rescue Marshall and Adams. After marching about 19 hours, he arrived at the camp where he had left his two companions and then led them back to Hut Point.

By about midnight on 4th March, 1909, they were all back on board Nimrod, heading out towards open sea and away from danger.

With the approach of the Antarctic winter, speed was essential, and Shackleton abandoned much of the expedition’s equipment and personal belongings rather than risk being trapped in the ice for another year, as had happened to Captain Robert Scott’s Discovery.

After reaching New Zealand, Shackleton made a brief phonograph record recounting the trek; then he sailed on to Dover. His wife, Emily, met him in mid-June, 1909, and they rode by train to London. The couple arrived at Charing Cross Station to a warm welcome.

A round of parties, lectures, dinners and receptions followed. On 28th June, 1909, Shackleton made a presentation to the Royal Geographical Society Fellows and guests, including Captain Scott. It was the culmination of all he and his companions had achieved. The Prince and Princess of Wales attended and presented the explorer with a medal from the Society. Later that year, he was knighted.

Shackleton died of a heart attack in 1922, just before his 48th birthday, and was buried in South Georgia in the Falkland Islands.

It was left to Roald Amundsen to reach the South Pole on 14th December, 1911. Captain Robert Scott and four companions duplicated the feat a month after Amundsen; but all of them perished on the return trek. Eight months later their bodies were found and remain there still.

Ninety years on, Shackleton would be astonished to learn that management theorists use him as an example of the best of leadership qualities. Such techniques as maintaining a positive outlook, organizational and marketing skills, providing a support system for colleagues, and the importance of loyalty were among Shackleton’s skills. His fame came not so much from what he did–or didn’t–achieve but from his ability to carry on under circumstances that would try abilities of lesser men.

Shackleton’s granddaughter paraphrased the comments of one of her grandfather’s companions when she said, “When all is lost, when there is no hope, pray for Shackleton. He will get you through.”

Related stories

Portfolio: Images of War as Landscape

Whether they produced battlefield images of the dead or daguerreotype portraits of common soldiers, […]

Jerrie Mock: Record-Breaking American Female Pilot

In 1964 an Ohio woman took up the challenge that had led to Amelia Earhart’s disappearance.

What Made Milwaukee Famous? This Blue Ribbon Beer

Frederick Pabst went from boat captain to hops connoisseur.

Gettysburg Had a Lasting Impact on Its Least Known Participants — Its Civilians

Travel along the famous sites of Gettysburg, from the Cashtown Inn to Lee’s headquarters, from the eyes of the locals.

Sir Ernest Shackleton

Discover the remarkable journey Shackleton undertook to save his crew from death

Sir Ernest Shackleton was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer, who made three expeditions to the continent, most famously in 1914 on the Endurance .

Who was Ernest Shackleton?

He was born in southern Ireland, but grew up in London. He joined the merchant navy when he was 16 and worked on many different ships. Shackleton was a romantic adventurer, who became interested in exploration and joined the Royal Geographical Society while still at sea. In 1901 he got a place on Captain Robert Falcon Scott 's first Antarctic expedition. This ignited his passion for Antarctic exploration.

When did Shackleton lead his first expedition to Antarctica?

In 1907, he led his own Antarctic expedition in the Nimrod . Other members of the expedition climbed Mount Erebus and reached the south magnetic pole. Shackleton himself led a party, which reached 97 miles short of the South Pole. He received a hero's welcome when he returned to England and was knighted.

What was the purpose of Shackleton’s 1914 Antarctic expedition?

In 1914, in command of a party on the ship Endurance , Shackleton set off to cross the Antarctic from one side to the other, from the Weddell Sea to the Ross Sea. As both Amundsen and Scott had reached the South Pole and the Americans had reached the North Pole, he saw this as the last great challenge.

What happened during this expedition?

Shackleton and his men set sail in August 1914, just as the war was starting in Europe. On 19 January 1915, Endurance became locked in the ice of the Weddell Sea. Over the course of the next nine months, the ship was gradually crushed, finally sinking on 27 October.

It proved impossible for the 28 men to drag their boats and stores across the frozen sea, so Shackleton camped on the ice and drifted with it. When the ice began to break up, the men launched the three boats and in dangerous conditions, managed to reach Elephant Island. This rocky and barren island was still more than 800 miles from the nearest inhabited land with people who could help them.

What did Shackleton decide to do?

He decided to leave most of the party behind, while he and five others set out on the James Caird to reach South Georgia, the nearest inhabited island, 800 miles away. He knew that he would find help there, at the Norwegian whaling stations on the north side. After 15 exhausting days at sea, the crew of the James Caird finally sighted South Georgia.

Did they find the help they needed?

No, because they were on the uninhabited side of the island. To get to the whaling stations, they had to cross the unmapped island to the other side. Shackleton led, taking Tom Crean and Frank Worsley, the expert navigator on the James Caird , who also had mountaineering experience. The journey involved a climb of nearly 3000 feet (914 metres). Apart from short breaks, they marched continuously for 36 hours, covering some 40 miles over mountainous and icy terrain until they finally reached the Stromness whaling station.

What happened to the other crewmen?

They were all rescued. Those on Elephant Island had to wait longer, until 30 August 1916, but were eventually picked up by Shackleton on a Chilean navy tug. All the men believed that their survival was due largely to his tremendous leadership.

What happened to Shackleton?

He died of a heart attack, on 5 January 1922. He was on his way to the Antarctic again, on board another ship the Quest , at Grytviken, South Georgia.

Shop gifts inspired by Shackleton's polar expeditions

- 0 Shopping Cart $ 0.00 -->

- Work with Us

- Latest News

- Image Archive

History of Shackleton’s Expedition

The British Antarctic Expedition 1907–09 Cape Royds

Ernest Shackleton was 33-years-old when he led his first expedition to Antarctica, determined to be the first to reach the Geographic South Pole.

His ship, Nimrod, departed England in August 1907, sailing via New Zealand before anchoring at Cape Royds in early 1908. The expedition recorded many firsts, including climbing the world’s southernmost volcano, Mt Erebus.

In late 1908, Shackleton led a party of four in an attempt to be the first to reach the Geographic South Pole. After man-hauling for two-and-a-half months, and 97 nautical miles from the Pole, Shackleton famously made the decision to turn for home. Today his only Antarctic base still stands at Cape Royds.

EXPEDITION BEGINNINGS

Since being invalided home with scurvy in 1903 from Robert Falcon Scott’s Discovery expedition, on which he was a third officer, Shackleton was fixated on getting back to the ice. Since his return from Antarctica he had a variety of jobs, which included magazine journalist, secretary of the Scottish Royal Geographical Society, and public relations work for a Glasgow steelworks. For over a year he drew up cost-cutting schemes and engineered introductions to rich businessmen, and by late 1906 was close to giving up.

Finally, his steelworks employer William Beardmore, and several other businessmen, agreed to guarantee a bank loan for £20,000, and Shackleton announced his plans on 11 February 1907. He would lead an expedition to Antarctica, with the primary goal of reaching the South Pole.

Shackleton intended to establish his base in King Edward VII Land, at the eastern end of the Ross Ice Shelf, and from there make the journey to the South Pole. He assured Scott that he didn’t intend to enter McMurdo Sound or make use of Scott’s old base at Hut Point, since Scott claimed rights not only to the hut, which he had built in 1902, but also to the route to the pole that he had pioneered.

Although funds were tight, Shackleton recruited 14 men who would make up the shore party of the expedition, and purchased the 200 ton Nimrod. He also procured a specially designed, prefabricated hut, plus 15 Manchurian ponies, nine dogs and an air-cooled, four-cylinder 11kW (15 hp) motorcar—the new Arrol-Johnston. Nimrod sailed from Torquay, England, bound for New Zealand, on 30 July 1907.

THE JOURNEY SOUTH

Nimrod sailed from Lyttelton, New Zealand, on New Year’s Day 1908. The ship was waved off by a crowd of thousands. The ship was dangerously overloaded with 255 tons of coal, equipment and food, and had just one metre of freeboard.

To save her limited cargo of coal, she was towed south by Koonya, a steel-built steamer. Within days Nimrod was taking on water through the scupper holes and wash ports—it was an arduous trip, which Shackleton likened to ‘a reluctant child being dragged to school.’ Finally the tow, of 1,510 miles (2,410 km), finished on 15 January with the sighting of the first icebergs.

Shackleton headed for an inlet on the edge of the Ross Ice Shelf where he intended to establish his base, but since his last visit, many kilometres of the ice shelf had caved into the sea. Faced by impenetrable pack ice he was forced to head for McMurdo Sound, despite his promise to Scott to avoid it.

Again he was frustrated by pack ice and unable to reach Hut Point near the site of the present-day United States McMurdo Station. Finally, he selected a site to winter-over at, 32km further north at Cape Royds, named by Captain Scott’s Discovery expedition after its meteorologist, Lieutenant Charles Royds, RN.

Stay in touch

Subscribe to our newsletter

Make a donation

Become a member.

Antarctic Heritage Trust 7 Ron Guthrey Road, Christchurch 8053, New Zealand Private Bag 4745, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand

© Copyright 2024, Antarctic Heritage Trust – Registered Charity: CC24071 Terms and Conditions – Privacy Policy

© Copyright 2024, Antarctic Heritage Trust Registered Charity: CC24071 Terms and Conditions – Privacy Policy

Adding gallery of images through Add Media

- Collectibles

Sir Ernest Shackleton: Heroic Antarctic Explorer and Legendary Leader

- by history tools

- May 26, 2024

Introduction

Sir Ernest Shackleton, the renowned Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer, has left an indelible mark on history through his exceptional leadership and unwavering determination. Born in 1874, Shackleton‘s thirst for adventure led him to participate in several groundbreaking expeditions during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration in the early 20th century. His most famous expedition, the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition (1914-1917), also known as the Endurance expedition, aimed to achieve the first land crossing of the Antarctic continent. Although the expedition faced insurmountable challenges, Shackleton‘s leadership and the crew‘s remarkable survival story have become the stuff of legend.

Early Life and Career

Ernest Henry Shackleton was born on February 15, 1874, in Kilkea, County Kildare, Ireland, to Anglo-Irish parents. His father, Henry Shackleton, was a doctor, and his mother, Henrietta Letitia Sophia Gavan, was the daughter of a Duchesse de Lignac [1]. The second of ten children, Shackleton and his family moved to London in 1884, where he struggled to fit in at school. Bored by his studies, he was drawn to the sea and the promise of adventure. At the age of 16, he joined the Merchant Navy, quickly rising through the ranks and becoming a Master Mariner by the age of 24 [2].

The Discovery Expedition and Rivalry with Scott

Shackleton‘s Antarctic career began in 1901 when he joined Robert Falcon Scott‘s Discovery expedition as a third officer. During this expedition, Shackleton, Scott, and Edward Wilson achieved a new "Furthest South" record, coming within 530 miles (853 km) of the South Pole [3]. However, Shackleton fell ill with scurvy and was sent home early, a decision that some historians believe may have been influenced by a growing rivalry between Shackleton and Scott [4].

The Nimrod Expedition

Determined to prove himself, Shackleton organized his own expedition in 1907, known as the Nimrod expedition. This expedition aimed to reach the South Pole and achieve several scientific objectives. Although the team fell short of reaching the pole, coming within 97 miles (156 km), they discovered the Beardmore Glacier, a crucial gateway to the Antarctic plateau, and made the first ascent of Mount Erebus, Antarctica‘s most active volcano [5]. The expedition also achieved significant scientific results, including the first comprehensive study of the region‘s geology, meteorology, and biology [6].

The Endurance Expedition: A Testament to Human Resilience

Shackleton‘s most famous expedition, the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, began in 1914. The plan was to cross the Antarctic continent via the South Pole, but fate had other plans. Shackleton received over 5,000 applications for his crew, personally selecting 56 men based on their character and ability to work well together [7]. The expedition‘s ship, Endurance, became trapped in pack ice in the Weddell Sea, and after months of being locked in the ice, the ship was eventually crushed, forcing the crew to abandon ship and set up camp on the floating ice.

For months, Shackleton and his crew drifted on the ice, hoping for a chance to reach land. When the ice began to break up, they took to their lifeboats and made a harrowing journey to the uninhabited Elephant Island. Realizing that rescue was unlikely, Shackleton made the bold decision to seek help. He and five of his men embarked on an epic 800-mile (1,287 km) open boat journey across the treacherous Southern Ocean to South Georgia Island, navigating by sextant and dead reckoning alone [8].

Upon reaching South Georgia, Shackleton and his men faced yet another challenge. They had landed on the wrong side of the island and were forced to trek over the island‘s uncharted, mountainous interior to reach a whaling station on the other side. Remarkably, all of the men survived this arduous journey. Shackleton then returned to Elephant Island to rescue the rest of his crew, and not a single life was lost during the entire ordeal [9].

Leadership and Legacy

Ernest Shackleton‘s legacy extends far beyond his Antarctic expeditions. His exceptional leadership skills, ability to maintain morale in the face of adversity, and unwavering commitment to his crew have made him a role model for leaders across the globe. Shackleton‘s leadership style was characterized by his ability to adapt to changing circumstances, his willingness to lead by example, and his genuine concern for the well-being of his men [10].

One of the most striking examples of Shackleton‘s leadership was his decision to give his own mittens to photographer Frank Hurley during the open boat journey, risking frostbite to ensure the safety of his crew [11]. Shackleton also made a point of sharing the hardships with his men, often taking on the most difficult tasks himself and maintaining a positive attitude in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds.

The psychological impact of the Endurance expedition on Shackleton and his men cannot be overstated. Many of the crew members suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and struggled to readjust to normal life after their ordeal [12]. Shackleton himself faced financial difficulties and personal struggles in the years following the expedition, but he remained committed to exploration and the pursuit of his dreams.

In the decades following his death, Shackleton‘s legacy was somewhat overshadowed by that of his rival, Robert Falcon Scott. However, in recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in Shackleton‘s life and achievements, with many historians and leaders recognizing him as a true hero and a master of crisis management [13].

The discovery of the wreck of the Endurance in March 2022, located nearly 10,000 feet (3,008 m) below the surface of the Weddell Sea, has further cemented Shackleton‘s place in history [14]. The wreck, which was found in remarkably good condition, serves as a tangible reminder of the incredible challenges faced by Shackleton and his crew and their unparalleled resilience in the face of adversity.

Sir Ernest Shackleton‘s life and expeditions continue to inspire people around the world, more than a century after his most famous journey. His unwavering commitment to his goals, his exceptional leadership skills, and his ability to maintain hope and determination in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds have made him a role model for generations of explorers and leaders.

As we face the challenges of the 21st century, Shackleton‘s legacy serves as a reminder of the enduring human spirit and the power of leadership in the face of adversity. His story is a testament to the enduring human qualities of courage, resilience, and the unwavering pursuit of one‘s dreams, encapsulated in his family motto: "By Endurance We Conquer."

- Huntford, R. (1985). Shackleton. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

- Lansing, A. (1959). Endurance: Shackleton‘s Incredible Voyage. New York: Carroll & Graf.

- Barczewski, S. (2007). Antarctic Destinies: Scott, Shackleton, and the Changing Face of Heroism. London: Hambledon Continuum.

- Fiennes, R. (2003). Captain Scott. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

- Riffenburgh, B. (2004). Nimrod: Ernest Shackleton and the Extraordinary Story of the 1907-09 British Antarctic Expedition. London: Bloomsbury.

- Shackleton, E. H. (1909). The Heart of the Antarctic. London: William Heinemann.

- Alexander, C. (1998). The Endurance: Shackleton‘s Legendary Antarctic Expedition. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Worsley, F. A. (1931). Endurance: An Epic of Polar Adventure. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Morrell, M., & Capparell, S. (2001). Shackleton‘s Way: Leadership Lessons from the Great Antarctic Explorer. New York: Viking.

- Perkins, D. N. T. (2000). Leading at the Edge: Leadership Lessons from the Extraordinary Saga of Shackleton‘s Antarctic Expedition. New York: AMACOM.

- Leane, E. (2012). Antarctica in Fiction: Imaginative Narratives of the Far South. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Koehn, N. F. (2003). Leadership in Crisis: Ernest Shackleton and the Epic Voyage of the Endurance. Boston: Harvard Business School.

- Endurance22 Expedition. (2022). Retrieved from https://endurance22.org/

Related posts:

- Tracing the Origins: German Tank Development in World War I

- Puyi: The Last Emperor of China – A Historian‘s Perspective

- Behind Enemy Lines: The Untold Story of an Audacious SAS Mission in WWII North Africa

- Lost at Sea: The Tragic Fate of the USS Indianapolis

- Stanislav Petrov: The Unsung Hero Who Saved the World from Nuclear Annihilation

- The Sudetenland Crisis of 1938: Anatomy of Appeasement

- The Battle of Britain: A View from the Luftwaffe‘s Perspective

- The Bay of Pigs Invasion: A Defining Moment in Cold War History

11 Facts About Sir Ernest Shackleton

By kat long | mar 23, 2022, 11:11 am edt.

Anglo-Irish explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton made four expeditions to Antarctica in the early 20th century, failing in many of his objectives but becoming a legendary leader in the process. January 5, 2022, marks the 100th anniversary of his death during his last expedition to the frozen continent. Here are the essential facts about the Boss 's life of adventure.

1. Before he went to Antarctica, Ernest Shackleton worked on merchant ships.

Ernest Shackleton was born in County Kildare, Ireland, on February 15, 1874. When he was 10, he moved with his family to Sydenham, then a suburb south of London, and attended nearby Dulwich College before signing up for the merchant navy at 16. He served on a ship carrying cargo between the UK and South America , and got his first taste of the turbulent seas around Cape Horn, with which he would become all too familiar later on.

2. Ernest Shackleton had a famous rivalry with Robert Falcon Scott.

Commander Robert Falcon Scott led the 1901-1904 British National Antarctic Expedition aboard the ship Discovery , with Shackleton serving as third officer. While the scientific crew carried out experiments, Scott, Shackleton, and Edward Wilson trekked over the continent’s unexplored interior to within 500 statute miles of the South Pole. Shackleton, however, came down with severe scurvy and was sent home in 1903. In his account of the voyage, Scott implied that Shackleton’s illness had prevented the party from reaching the Pole. Shackleton, insulted, began planning an even more ambitious Antarctic voyage. The rivalry was still strong in 1907, when Scott complained to a cartographer about having his name alongside Shackleton's on a new map.

3. Ernest Shackleton set a farthest south record.

Shackleton commanded the Nimrod expedition from 1907 to 1909 and achieved a handful of significant firsts: five men made the first ascent of Mount Erebus , a live volcano , and the crew drove the first motorcar in Antarctica. Shackleton and three others tried again for the South Pole, but a critical shortage of food forced them to retreat just 97 nautical miles (111.6 statute miles) from their goal. “The last day out we have shot our bolt and the tale is 88°23’ S[outh], 162° E[ast],” he wrote in his diary. “Homeward bound. Whatever regrets may be we have done our best.”

Despite falling short of their destination, Shackleton returned to England with a new farthest south record. He was lauded for his wise decision to save his men’s lives by turning around—a glimpse of the leadership that would later become his defining characteristic.

4. Ernest Shackleton testified at the Titanic inquiry.

After returning from his second Antarctic trip, Shackleton was considered a leading expert in polar phenomena. For that reason, he was called to testify at the hearing following the sinking of the Titanic in 1912. The explorer delivered his opinion on the conditions that would have made the North Atlantic iceberg difficult for the navigators to see until it was too late. “With a dead calm sea there is no sign at all to give you any indication that there is anything there,” he said .

5. Ernest Shackleton’s alleged advertisement for his next voyage wasn’t optimistic.

Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen became the first man to reach the South Pole on December 14, 1911, beating Shackleton’s nemesis Robert Falcon Scott and his four-man team by more than a month (Scott's party perished on their return). With that trophy claimed, Shackleton refocused on launching the first expedition to cross Antarctica on foot. When it came time to hire his crew for the grandly titled Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition in the ship Endurance , Shackleton supposedly ran an advertisement in a newspaper that didn’t mince words:

"MEN WANTED for hazardous journey, small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful, honor and recognition in case of success. Ernest Shackleton, 4 Burlington Street."

Historians have been unable to locate a copy of the original advertisement, however, leading many to conclude that it’s probably a myth.

6. Ernest Shackleton and five men sailed 800 miles in an open boat …

The Endurance left Plymouth, England, in August 1914 with a crew of 26; Shackleton and second-in-command Frank Wild joined the ship later. By January 1915, the vessel was stuck in pack ice, and finally sank on November 21, 1915 [ PDF ], having never reached the continent. Shackleton and the crew set up camp on the ice floe and drifted helplessly with the currents for the next four months. Austral summer temperatures between December and April gradually melted their floe, and when the ice broke apart on April 9, 1916, they jumped into three lifeboats and sailed for the nearest land—an uninhabited speck called Elephant Island, 150 miles north-northeast of the Antarctic Peninsula.

After landing, Shackleton—who knew rescue was unlikely—made the decision to sail once again for help. He took five other men on their 23-foot lifeboat, the James Caird , and headed for the whaling station on South Georgia. The tiny, isolated island was 800 miles away, across the world’s most dangerous ocean. Despite violent storms and icy seawater constantly sloshing over their heads—not to mention sheer exhaustion—the Endurance 's captain Frank Worsley was able to navigate the boat, and they landed barely alive two weeks later, on May 10, 1916.

7. … And then Shackleton and two companions climbed over uncharted glaciers.

Unfortunately, the James Caird landed on the wrong side of South Georgia, and it was too dangerous to sail around to the whaling station. Despite their extreme fatigue and hunger, Shackleton, Worsley, and the Endurance ’s second officer Tom Crean hiked across the glacier -covered mountain range forming the backbone of the island. According to Alfred Lansing's definitive account Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage , they knew they had made it when they heard the station’s bell signaling the start of the workday, at precisely 6:30 a.m. on May 20, 1916.

In the days and weeks afterward, Shackleton retrieved the three men left at the other side of the island and (after several attempts thwarted by sea ice) chartered a ship in August 1916 to rescue those stranded on Elephant Island. All 28 of the Endurance ’s crew survived.

8. Business coaches teach Ernest Shackleton’s leadership style.

Shackleton is famous for not losing a man, but even before that, he made strategic decisions to preserve his crew’s health and spirits during their many months adrift. In one example, when he chose his crew for the boat journey, he picked carpenter Henry “Chippy” McNeish, despite having a strained relationship with him. The Boss believed leaving McNeish behind at Elephant Island would create the potential for discord among the castaways. Shackleton’s skills as a leader, especially his example of resilience in extreme situations, has inspired multiple business guides , books , and case studies .

9. Ernest Shackleton volunteered in World War I.

When they returned from Antarctica, a surprising number of the Endurance ’s crew served in World War I. Among them, photographer Frank Hurley worked as a combat photojournalist, Wild volunteered as a Royal Navy transport officer in Russia, and Shackleton himself served in the North Russian Expeditionary Force in that country’s civil war.

After the armistice, Shackleton began planning his next quest—appropriately aboard the ship Quest —financed by the philanthropist John Quiller Rowett. The Boss and his crew, which included eight Endurance veterans, arrived in South Georgia on January 4, 1922. The following morning, Shackleton died suddenly from coronary thrombosis at age 47. He was buried in the Norwegian whalers’ cemetery at the Grytviken whaling station, according to his wife’s wishes.

10. Modern-day explorers recreated Ernest Shackleton’s legendary boat journey.

In 2014, adventurer Tim Jarvis led a crew of five men in a recreation of Shackleton’s open-boat journey from Elephant Island to South Georgia on the 100th anniversary of the feat. They traveled in a wooden replica of the James Caird , used century-old equipment to navigate and sail, and even wore the same type of Edwardian-era clothing as Shackleton’s men. Like the earlier explorers, Jarvis and crew faced down tremendous waves, storms, cold, and icy winds before crossing South Georgia’s glaciers on foot to the old whaling station. A documentary of the expedition aired on PBS.

11. Explorers finally found Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance .

According to Worsley's calculations , the Endurance was crushed by ice at 68°39′30″ South Latitude, 52°26′30″ West Longitude, nearly 200 miles east of the Antarctic Peninsula. Julian Dowdeswell, a professor of physical geography at Cambridge University, organized an expedition to the site in 2019 to scan the conditions on the seafloor and discover the Endurance ’s final resting place. Though weather and ice conditions prevented a thorough search, Dowdeswell found minimal sediment drift and ice scouring at the site. In 2022, an expedition organized by the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust located the 107-year-old shipwreck, in nearly 10,000 feet of water, just four miles away from Worsley's last recorded position.

"This is by far the finest wooden shipwreck I have ever seen," Mensun Bound, the expedition's director of exploration, said in a statement . "It is upright, well proud of the seabed, intact, and in a brilliant state of preservation. You can even see 'Endurance' arced across the stern, directly below the taffrail. This is a milestone in polar history."

Additional sources: Endurance: Shackleton’s Incredible Voyage ; Shackleton’s Boat Journey

A version of this story ran in 2021; it has been updated for 2022.

Antarctic: Exhibition recalls Ernest Shackleton's final quest

- Published 17 September 2021

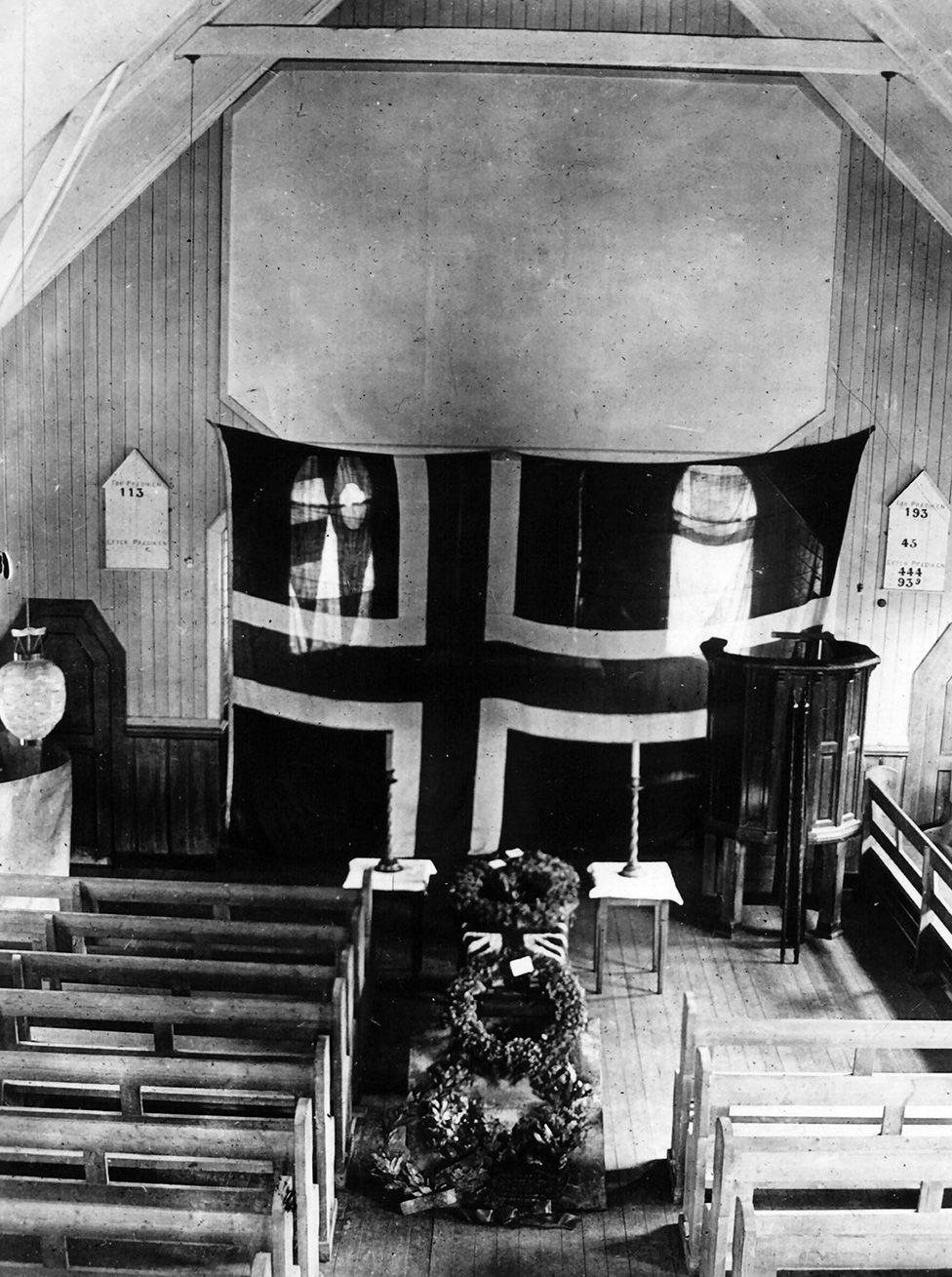

The Quest's crew paid their respects at the grave of their leader on return to South Georgia

It's 100 years to the day since Antarctic explorer Ernest Shackleton set out on his final expedition.

Leaving London through Tower Bridge, and hailed by a large crowd, his intention was to map still uncharted coastal regions of the White Continent.

But he never managed it, dying of a heart attack before reaching the polar south at the island of South Georgia.

To mark Shackleton's passing, the South Georgia Heritage Trust , external (SGHT) is mounting a special exhibition.

It tells the story of that final expedition, which continued without him, and includes some fascinating archive material recalling his death and burial at the British Overseas Territory.

New map traces Shackleton's footsteps

Renewed quest to find Shackleton's lost ship

Blue whales have 'rediscovered' South Georgia

The Quest continued south to Antarctica to try to complete the goals of the expedition

You can see, for example, the banners that were walked in front of Shackleton's coffin, and the wooden cross that was erected atop the memorial cairn built by his crewmen.

Some of the artefacts have not been seen publicly before, or at least haven't been seen in their proper context. And some objects have been loaned from other museums.

For now, the exhibition is online only , external , but eventually the physical items will be moved to the museum at Grytviken on South Georgia, which attracts a lot of tourists who are drawn to the island's spectacular scenery and wildlife.

Lady Shackleton insisted her husband be buried on South Georgia and redirected his remains

Covid difficulties mean the artefacts won't be in place for the 100th anniversary of the explorer's death on 5 January, but this actually presents an opportunity says Jayne Pierce, the SGHT's museum curator.

"The good thing about the exhibition being online is that anyone can see it. Shackleton has a lot of super fans who never would be able to get to South Georgia, and this way they can see what we've put together," she told BBC News.

The 17 September, 1921, departure from St Katherine Dock was the beginning of what turned out to be - literally - Shackleton's "last quest".

Sir Ernest Shackleton: Sailors who survived the Endurance's sinking joined The Boss again on the Quest

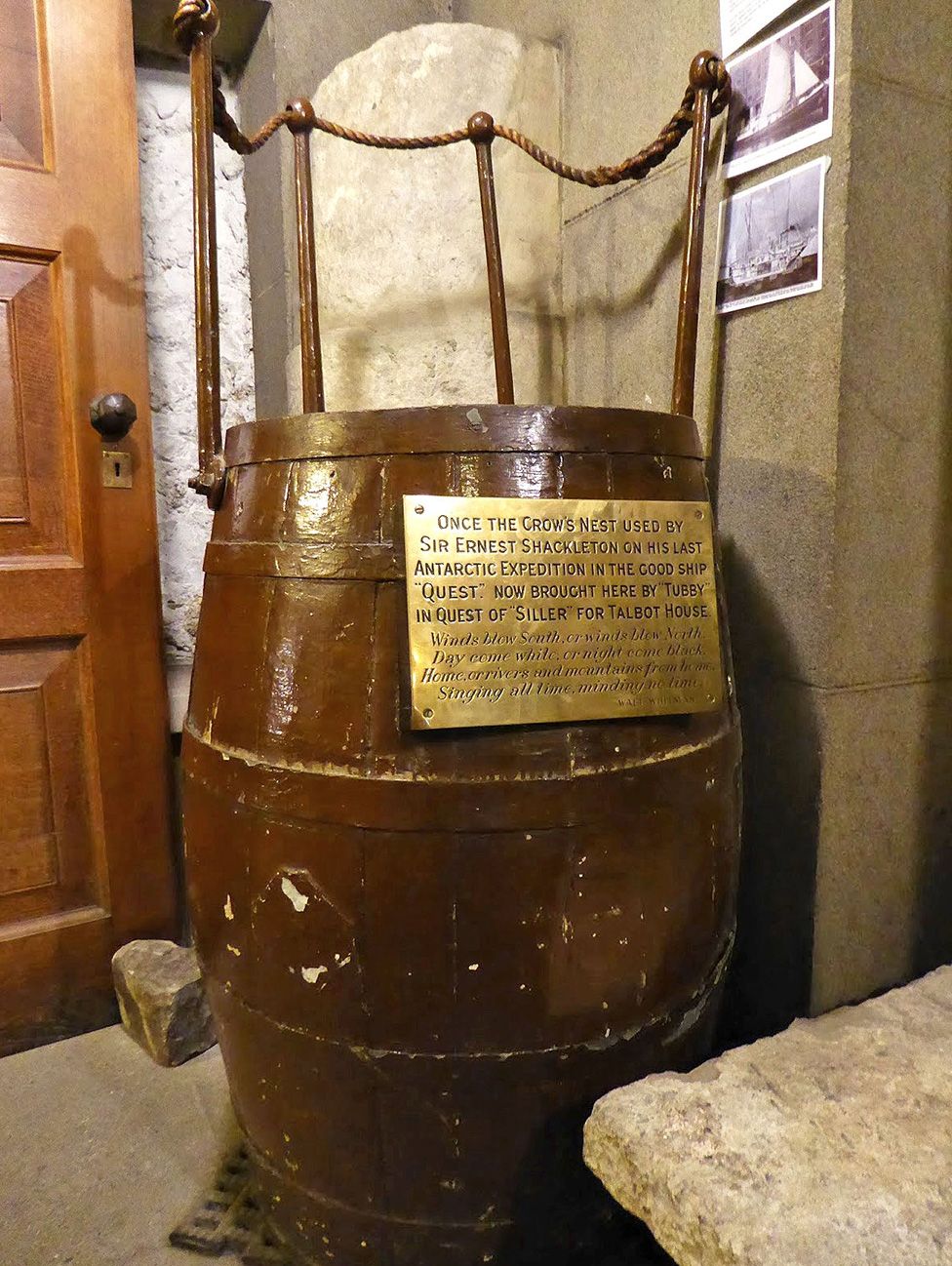

"Quest" was the name of the ship in which his team would travel south.

A Norwegian sealer, the vessel was converted for the purpose and was fitted with a crow's nest to aid navigation through sea-ice and to look out for hazards such as big icebergs.

That crow's nest - not much more than a simple barrel - still exists and has been included in the exhibition. It's been scanned so that visitors can turn it around online.

"When we started looking at what to do to mark Shackleton's death, we thought we should expand the exhibition to also tell the story of the expedition, even though it wasn't that remarkable and he himself never actually carried it through," explained Jayne Pierce.

"But the Quest expedition is still important because it represented his last big push in life. He was desperate to go, and it was almost as if he knew his time was limited."

The crowsnest was taken off the Quest and stored after the expedition

The Quest expedition (more properly called the Shackleton-Rowett Expedition) was the explorer's fourth Antarctic venture. He's most famous, of course, for his third - the ill-fated Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1914-1917.

Trapped in sea-ice for over 10 months, his Endurance ship drifted around the Weddell Sea until ultimately it was crushed by the floes and dropped to the deep. How Shackleton and his men then made their escape on foot and in lifeboats is the stuff of legend.

Two banners in the Norwegian style were carried in front of Shackleton's coffin procession

Shackleton "mega-fans" now visit South Georgia to retrace the final stages of the escape which saw him walk over the island's mountains to raise the alarm at the Stromness whaling station just along the coast from Grytviken.

"His ties to South Georgia are therefore deep," the curator said.

"After he died they tried to send his remains home but when they reached Montevideo, word reached his wife and she said 'no, he should be buried in South Georgia because that's where his true soul was'."

This turn of events was certainly unexpected for the crew of the Quest. After the death of "The Boss", they had continued on to Antarctica to conduct the planned mapping work, and so were surprised to find his grave at South Georgia when they came back through.

Cruise ships visit the islands, drawn to the breath-taking landscapes - but not during Covid

Asked to explain the enduring appeal of Shackleton, Jayne Pierce says it has something to do with the romance of the so-called "Heroic Age" of Antarctic exploration.

"I guess today technology makes everything so easy. We can go to space, we can go to the bottom of the ocean, we can go to the South Pole. But for Shackleton, these were all unknowns. They didn't have the technologies. And so for lots of people there's this romance to what Shackleton did and to the idea of the wilderness that doesn't really exist anymore."

Shackleton will be in the news early next year when another mission is mounted to try to find and photograph the wreck of the Endurance on the floor of the Weddell Sea.

The SGHT online exhibition can be found here , external .

Grytviken today. The cemetery is the white square at centre-left

It is hoped that the exhibition at the South Georgia Museum can be opened at some point during the coming season or the next, depending on travel restrictions. The online exhibition can be found here , external .

Related Topics

- Earth science

- Ernest Shackleton

You are eligible for free shipping!

Your basket is empty

Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

Polar historian and author Michael Smith details the expedition that is widely regarded as the greatest feat of survival in the history of exploration, the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, when his ship was trapped and crushed by sea ice, forcing the crew onto drifting ice flows…

Sir Ernest Shackleton’s towering ambition and eagerness to explore the unknown led him to undertake the boldest adventure of his life, the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. Although the expedition failed, it would be remembered by generations as the greatest feat of survival in the history of exploration.

By 1913, only four years after turning back 97 miles from the South Pole, Shackleton was looking for a new challenge. Roald Amundsen and Captain Scott had conquered the South Pole and Robert Peary had claimed to have stood at the North Pole, which left him with limited options.