Sustainable tourism

Related sdgs, promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable ....

Description

Publications.

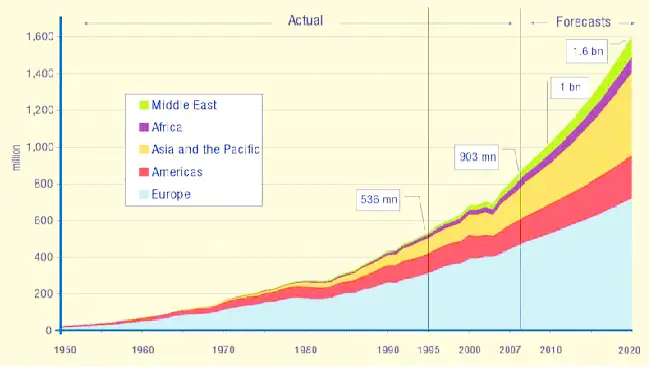

Tourism is one of the world's fastest growing industries and an important source of foreign exchange and employment, while being closely linked to the social, economic, and environmental well-being of many countries, especially developing countries. Maritime or ocean-related tourism, as well as coastal tourism, are for example vital sectors of the economy in small island developing States (SIDS) and coastal least developed countries (LDCs) (see also: The Potential of the Blue Economy report as well as the Community of Ocean Action on sustainable blue economy).

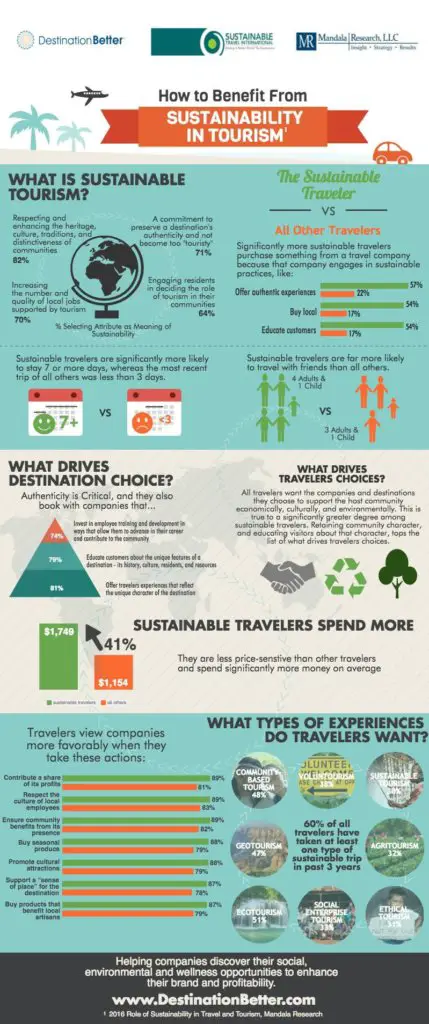

The World Tourism Organization defines sustainable tourism as “tourism that takes full account of its current and future economic, social and environmental impacts, addressing the needs of visitors, the industry, the environment and host communities".

Based on General assembly resolution 70/193, 2017 was declared as the International Year of Sustainable Tourism for Development.

In the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development SDG target 8.9, aims to “by 2030, devise and implement policies to promote sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture and products”. The importance of sustainable tourism is also highlighted in SDG target 12.b. which aims to “develop and implement tools to monitor sustainable development impacts for sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture and products”.

Tourism is also identified as one of the tools to “by 2030, increase the economic benefits to Small Island developing States and least developed countries” as comprised in SDG target 14.7.

In the Rio+20 outcome document The Future We want, sustainable tourism is defined by paragraph 130 as a significant contributor “to the three dimensions of sustainable development” thanks to its close linkages to other sectors and its ability to create decent jobs and generate trade opportunities. Therefore, Member States recognize “the need to support sustainable tourism activities and relevant capacity-building that promote environmental awareness, conserve and protect the environment, respect wildlife, flora, biodiversity, ecosystems and cultural diversity, and improve the welfare and livelihoods of local communities by supporting their local economies and the human and natural environment as a whole. ” In paragraph 130, Member States also “call for enhanced support for sustainable tourism activities and relevant capacity-building in developing countries in order to contribute to the achievement of sustainable development”.

In paragraph 131, Member States “encourage the promotion of investment in sustainable tourism, including eco-tourism and cultural tourism, which may include creating small- and medium-sized enterprises and facilitating access to finance, including through microcredit initiatives for the poor, indigenous peoples and local communities in areas with high eco-tourism potential”. In this regard, Member States also “underline the importance of establishing, where necessary, appropriate guidelines and regulations in accordance with national priorities and legislation for promoting and supporting sustainable tourism”.

In 2002, the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg called for the promotion of sustainable tourism development, including non-consumptive and eco-tourism, in Chapter IV, paragraph 43 of the Johannesburg Plan of Implementation.

At the Johannesburg Summit, the launch of the “Sustainable Tourism – Eliminating Poverty (ST-EP) initiative was announced. The initiative was inaugurated by the World Tourism Organization, in collaboration with UNCTAD, in order to develop sustainable tourism as a force for poverty alleviation.

The UN Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD) last reviewed the issue of sustainable tourism in 2001, when it was acting as the Preparatory Committee for the Johannesburg Summit.

The importance of sustainable tourism was also mentioned in Agenda 21.

For more information and documents on this topic, please visit this link

UNWTO Annual Report 2015

2015 was a landmark year for the global community. In September, the 70th Session of the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a universal agenda for planet and people. Among the 17 SDGs and 169 associated targets, tourism is explicitly featured in Goa...

UNWTO Annual Report 2016

In December 2015, the United Nations General Assembly declared 2017 as the International Year of Sustainable Tourism for Development. This is a unique opportunity to devote a year to activities that promote the transformational power of tourism to help us reach a better future. This important cele...

Emerging Issues for Small Island Developing States

The 2012 UNEP Foresight Process on Emerging Global Environmental Issues primarily identified emerging environmental issues and possible solutions on a global scale and perspective. In 2013, UNEP carried out a similar exercise to identify priority emerging environmental issues that are of concern to ...

Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

This Agenda is a plan of action for people, planet and prosperity. It also seeks to strengthen universal peace in larger freedom, We recognize that eradicating poverty in all its forms and dimensions, including extreme poverty, is the greatest global challenge and an indispensable requirement for su...

15 Years of the UNWTO World Tourism Network on Child Protection: A Compilation of Good Practices

Although it is widely recognized that tourism is not the cause of child exploitation, it can aggravate the problem when parts of its infrastructure, such as transport networks and accommodation facilities, are exploited by child abusers for nefarious ends. Additionally, many other factors that contr...

Towards Measuring the Economic Value of Wildlife Watching Tourism in Africa

Set against the backdrop of the ongoing poaching crisis driven by a dramatic increase in the illicit trade in wildlife products, this briefing paper intends to support the ongoing efforts of African governments and the broader international community in the fight against poaching. Specifically, this...

Status and Trends of Caribbean Coral Reefs: 1970-2012

Previous Caribbean assessments lumped data together into a single database regardless of geographic location, reef environment, depth, oceanographic conditions, etc. Data from shallow lagoons and back reef environments were combined with data from deep fore-reef environments and atolls. Geographic c...

Natural Resources Forum: Special Issue Tourism

The journal considers papers on all topics relevant to sustainable development. In addition, it dedicates series, issues and special sections to specific themes that are relevant to the current discussions of the United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD)....

Thailand: Supporting Sustainable Development in Thailand: A Geographic Clusters Approach

Market forces and government policies, including the Tenth National Development Plan (2007-2012), are moving Thailand toward a more geographically specialized economy. There is a growing consensus that Thailand’s comparative and competitive advantages lie in amenity services that have high reliance...

Road Map on Building a Green Economy for Sustainable Development in Carriacou and Petite Martinique, Grenada

This publication is the product of an international study led by the Division for Sustainable Development (DSD) of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA) in cooperation with the Ministry of Carriacou and Petite Martinique Affairs and the Ministry of Environment, Foreig...

Natural Resources Forum, a United Nations Sustainable Development Journal (NRF)

Natural Resources Forum, a United Nations Sustainable Development Journal, seeks to address gaps in current knowledge and stimulate relevant policy discussions, leading to the implementation of the sustainable development agenda and the achievement of the Sustainable...

UN Ocean Conference 2025

Our Ocean, Our Future, Our Responsibility “The ocean is fundamental to life on our planet and to our future. The ocean is an important source of the planet’s biodiversity and plays a vital role in the climate system and water cycle. The ocean provides a range of ecosystem services, supplies us with

UN Ocean Conference 2022

The UN Ocean Conference 2022, co-hosted by the Governments of Kenya and Portugal, came at a critical time as the world was strengthening its efforts to mobilize, create and drive solutions to realize the 17 Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.

58th Session of the Commission for Social Development – CSocD58

22nd general assembly of the united nations world tourism organization, world tourism day 2017 official celebration.

This year’s World Tourism Day, held on 27 September, will be focused on Sustainable Tourism – a Tool for Development. Celebrated in line with the 2017 International Year of Sustainable Tourism for Development, the Day will be dedicated to exploring the contribution of tourism to the Sustainable Deve

World Tourism Day 2016 Official Celebration

Accessible Tourism for all is about the creation of environments that can cater for the needs of all of us, whether we are traveling or staying at home. May that be due to a disability, even temporary, families with small children, or the ageing population, at some point in our lives, sooner or late

4th Global Summit on City Tourism

The World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO) and the Regional Council for Tourism of Marrakesh with support of the Government of Morroco are organizing the 4th Global Summit on City Tourism in Marrakesh, Morroco (9-10 December 2015). International experts in city tourism, representatives of city DMOs, of

2nd Euro-Asian Mountain Resorts Conference

The World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO) and Ulsan Metropolitan City with support of the Government of the Republic of Korea are organizing the 2nd Euro-Asian Mountain Resorts Conference, in Ulsan, Republic of Korea (14 - 16 October 2015). Under the title “Paving the Way for a Bright Future for Mounta

21st General Assembly of the United Nations World Tourism Organization

Unwto regional conference enhancing brand africa - fostering tourism development.

Tourism is one of the Africa’s most promising sectors in terms of development, and represents a major opportunity to foster inclusive development, increase the region’s participation in the global economy and generate revenues for investment in other activities, including environmental preservation.

- January 2017 International Year of Tourism In the context of the universal 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the International Year aims to support a change in policies, business practices and consumer behavior towards a more sustainable tourism sector that can contribute to the SDGs.

- January 2015 Targets 8.9, 12 b,14.7 The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development commits Member States, through Sustainable Development Goal Target 8.9 to “devise and implement policies to promote sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture and products”. The importance of sustainable tourism, as a driver for jobs creation and the promotion of local culture and products, is also highlighted in Sustainable Development Goal target 12.b. Tourism is also identified as one of the tools to “increase [by 2030] the economic benefits to Small Island developing States and least developed countries”, through Sustainable Development Goals Target 14.7.

- January 2012 Future We Want (Para 130-131) Sustainable tourism is defined as a significant contributor “to the three dimensions of sustainable development” thanks to its close linkages to other sectors and its ability to create decent jobs and generate trade opportunities. Therefore, Member States recognize “the need to support sustainable tourism activities and relevant capacity-building that promote environmental awareness, conserve and protect the environment, respect wildlife, flora, biodiversity, ecosystems and cultural diversity, and improve the welfare and livelihoods of local communities” as well as to “encourage the promotion of investment in sustainable tourism, including eco-tourism and cultural tourism, which may include creating small and medium sized enterprises and facilitating access to finance, including through microcredit initiatives for the poor, indigenous peoples and local communities in areas with high eco-tourism potential”.

- January 2009 Roadmap for Recovery UNWTO announced in March 2009 the elaboration of a Roadmap for Recovery to be finalized by UNWTO’s General Assembly, based on seven action points. The Roadmap includes a set of 15 recommendations based on three interlocking action areas: resilience, stimulus, green economy aimed at supporting the tourism sector and the global economy.

- January 2008 Global Sustainable Tourism Criteria The Global Sustainable Tourism Criteria represent the minimum requirements any tourism business should observe in order to ensure preservation and respect of the natural and cultural resources and make sure at the same time that tourism potential as tool for poverty alleviation is enforced. The Criteria are 41 and distributed into four different categories: 1) sustainability management, 2) social and economic 3) cultural 4) environmental.

- January 2003 WTO becomes a UN specialized body By Resolution 453 (XV), the Assembly agreed on the transformation of the WTO into a United Nations specialized body. Such transformation was later ratified by the United Nations General Assembly with the adoption of Resolution A/RES/58/232.

- January 2003 1st Int. Conf. on Climate Change and Tourism The conference was organized in order to gather tourism authorities, organizations, businesses and scientists to discuss on the impact that climate change can have on the tourist sector. The event took place from 9 till 11 April 2003 in Djerba, Tunisia.

- January 2002 World Ecotourism Summit Held in May 2002, in Quebec City, Canada, the Summit represented the most important event in the framework of the International Year of Ecosystem. The Summit identified as main themes: ecotourism policy and planning, regulation of ecotourism, product development, marketing and promotion of ecotourism and monitoring costs and benefits of ecotourism.

- January 1985 Tourism Bill of Rights and Tourist Code At the World Tourism Organization Sixth Assembly held in Sofia in 1985, the Tourism Bill of Rights and Tourist Code were adopted, setting out the rights and duties of tourists and host populations and formulating policies and action for implementation by states and the tourist industry.

- January 1982 Acapulco Document Adopted in 1982, the Acapulco Document acknowledges the new dimension and role of tourism as a positive instrument towards the improvement of the quality of life for all peoples, as well as a significant force for peace and international understanding. The Acapulco Document also urges Member States to elaborate their policies, plans and programmes on tourism, in accordance with their national priorities and within the framework of the programme of work of the World Tourism Organization.

What Is Sustainable Tourism and Why Is It Important?

Sustainable management and socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental impacts are the four pillars of sustainable tourism

- Chapman University

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/HaleyMast-2035b42e12d14d4abd433e014e63276c.jpg)

- Harvard University Extension School

- Sustainable Fashion

- Art & Media

What Makes Tourism Sustainable?

The role of tourists, types of sustainable tourism.

Sustainable tourism considers its current and future economic, social, and environmental impacts by addressing the needs of its ecological surroundings and the local communities. This is achieved by protecting natural environments and wildlife when developing and managing tourism activities, providing only authentic experiences for tourists that don’t appropriate or misrepresent local heritage and culture, or creating direct socioeconomic benefits for local communities through training and employment.

As people begin to pay more attention to sustainability and the direct and indirect effects of their actions, travel destinations and organizations are following suit. For example, the New Zealand Tourism Sustainability Commitment is aiming to see every New Zealand tourism business committed to sustainability by 2025, while the island country of Palau has required visitors to sign an eco pledge upon entry since 2017.

Tourism industries are considered successfully sustainable when they can meet the needs of travelers while having a low impact on natural resources and generating long-term employment for locals. By creating positive experiences for local people, travelers, and the industry itself, properly managed sustainable tourism can meet the needs of the present without compromising the future.

What Is Sustainability?

At its core, sustainability focuses on balance — maintaining our environmental, social, and economic benefits without using up the resources that future generations will need to thrive. In the past, sustainability ideals tended to lean towards business, though more modern definitions of sustainability highlight finding ways to avoid depleting natural resources in order to keep an ecological balance and maintain the quality of environmental and human societies.

Since tourism impacts and is impacted by a wide range of different activities and industries, all sectors and stakeholders (tourists, governments, host communities, tourism businesses) need to collaborate on sustainable tourism in order for it to be successful.

The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) , which is the United Nations agency responsible for the promotion of sustainable tourism, and the Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) , the global standard for sustainable travel and tourism, have similar opinions on what makes tourism sustainable. By their account, sustainable tourism should make the best use of environmental resources while helping to conserve natural heritage and biodiversity, respect the socio-culture of local host communities, and contribute to intercultural understanding. Economically, it should also ensure viable long-term operations that will provide benefits to all stakeholders, whether that includes stable employment to locals, social services, or contributions to poverty alleviation.

The GSTC has developed a series of criteria to create a common language about sustainable travel and tourism. These criteria are used to distinguish sustainable destinations and organizations, but can also help create sustainable policies for businesses and government agencies. Arranged in four pillars, the global baseline standards include sustainable management, socioeconomic impact, cultural impacts, and environmental impacts.

Travel Tip:

The GSTC is an excellent resource for travelers who want to find sustainably managed destinations and accommodations and learn how to become a more sustainable traveler in general.

Environment

Protecting natural environments is the bedrock of sustainable tourism. Data released by the World Tourism Organization estimates that tourism-based CO2 emissions are forecast to increase 25% by 2030. In 2016, tourism transport-related emissions contributed to 5% of all man-made emissions, while transport-related emissions from long-haul international travel were expected to grow 45% by 2030.

The environmental ramifications of tourism don’t end with carbon emissions, either. Unsustainably managed tourism can create waste problems, lead to land loss or soil erosion, increase natural habitat loss, and put pressure on endangered species . More often than not, the resources in these places are already scarce, and sadly, the negative effects can contribute to the destruction of the very environment on which the industry depends.

Industries and destinations that want to be sustainable must do their part to conserve resources, reduce pollution, and conserve biodiversity and important ecosystems. In order to achieve this, proper resource management and management of waste and emissions is important. In Bali, for example, tourism consumes 65% of local water resources, while in Zanzibar, tourists use 15 times as much water per night as local residents.

Another factor to environmentally focused sustainable tourism comes in the form of purchasing: Does the tour operator, hotel, or restaurant favor locally sourced suppliers and products? How do they manage their food waste and dispose of goods? Something as simple as offering paper straws instead of plastic ones can make a huge dent in an organization’s harmful pollutant footprint.

Recently, there has been an uptick in companies that promote carbon offsetting . The idea behind carbon offsetting is to compensate for generated greenhouse gas emissions by canceling out emissions somewhere else. Much like the idea that reducing or reusing should be considered first before recycling , carbon offsetting shouldn’t be the primary goal. Sustainable tourism industries always work towards reducing emissions first and offset what they can’t.

Properly managed sustainable tourism also has the power to provide alternatives to need-based professions and behaviors like poaching . Often, and especially in underdeveloped countries, residents turn to environmentally harmful practices due to poverty and other social issues. At Periyar Tiger Reserve in India, for example, an unregulated increase in tourists made it more difficult to control poaching in the area. In response, an eco development program aimed at providing employment for locals turned 85 former poachers into reserve gamekeepers. Under supervision of the reserve’s management staff, the group of gamekeepers have developed a series of tourism packages and are now protecting land instead of exploiting it. They’ve found that jobs in responsible wildlife tourism are more rewarding and lucrative than illegal work.

Flying nonstop and spending more time in a single destination can help save CO2, since planes use more fuel the more times they take off.

Local Culture and Residents

One of the most important and overlooked aspects of sustainable tourism is contributing to protecting, preserving, and enhancing local sites and traditions. These include areas of historical, archaeological, or cultural significance, but also "intangible heritage," such as ceremonial dance or traditional art techniques.

In cases where a site is being used as a tourist attraction, it is important that the tourism doesn’t impede access to local residents. For example, some tourist organizations create local programs that offer residents the chance to visit tourism sites with cultural value in their own countries. A program called “Children in the Wilderness” run by Wilderness Safaris educates children in rural Africa about the importance of wildlife conservation and valuable leadership development tools. Vacations booked through travel site Responsible Travel contribute to the company’s “Trip for a Trip” program, which organizes day trips for disadvantaged youth who live near popular tourist destinations but have never had the opportunity to visit.

Sustainable tourism bodies work alongside communities to incorporate various local cultural expressions as part of a traveler’s experiences and ensure that they are appropriately represented. They collaborate with locals and seek their input on culturally appropriate interpretation of sites, and train guides to give visitors a valuable (and correct) impression of the site. The key is to inspire travelers to want to protect the area because they understand its significance.

Bhutan, a small landlocked country in South Asia, has enforced a system of all-inclusive tax for international visitors since 1997 ($200 per day in the off season and $250 per day in the high season). This way, the government is able to restrict the tourism market to local entrepreneurs exclusively and restrict tourism to specific regions, ensuring that the country’s most precious natural resources won’t be exploited.

Incorporating volunteer work into your vacation is an amazing way to learn more about the local culture and help contribute to your host community at the same time. You can also book a trip that is focused primarily on volunteer work through a locally run charity or non profit (just be sure that the job isn’t taking employment opportunities away from residents).

It's not difficult to make a business case for sustainable tourism, especially if one looks at a destination as a product. Think of protecting a destination, cultural landmark, or ecosystem as an investment. By keeping the environment healthy and the locals happy, sustainable tourism will maximize the efficiency of business resources. This is especially true in places where locals are more likely to voice their concerns if they feel like the industry is treating visitors better than residents.

Not only does reducing reliance on natural resources help save money in the long run, studies have shown that modern travelers are likely to participate in environmentally friendly tourism. In 2019, Booking.com found that 73% of travelers preferred an eco-sustainable hotel over a traditional one and 72% of travelers believed that people need to make sustainable travel choices for the sake of future generations.

Always be mindful of where your souvenirs are coming from and whether or not the money is going directly towards the local economy. For example, opt for handcrafted souvenirs made by local artisans.

Growth in the travel and tourism sectors alone has outpaced the overall global economy growth for nine years in a row. Prior to the pandemic, travel and tourism accounted for an $9.6 trillion contribution to the global GDP and 333 million jobs (or one in four new jobs around the world).

Sustainable travel dollars help support employees, who in turn pay taxes that contribute to their local economy. If those employees are not paid a fair wage or aren’t treated fairly, the traveler is unknowingly supporting damaging or unsustainable practices that do nothing to contribute to the future of the community. Similarly, if a hotel doesn’t take into account its ecological footprint, it may be building infrastructure on animal nesting grounds or contributing to excessive pollution. The same goes for attractions, since sustainably managed spots (like nature preserves) often put profits towards conservation and research.

Costa Rica was able to turn a severe deforestation crisis in the 1980s into a diversified tourism-based economy by designating 25.56% of land protected as either a national park, wildlife refuge, or reserve.

While traveling, think of how you would want your home country or home town to be treated by visitors.

Are You a Sustainable Traveler?

Sustainable travelers understand that their actions create an ecological and social footprint on the places they visit. Be mindful of the destinations , accommodations, and activities you choose, and choose destinations that are closer to home or extend your length of stay to save resources. Consider switching to more environmentally friendly modes of transportation such as bicycles, trains, or walking while on vacation. Look into supporting locally run tour operations or local family-owned businesses rather than large international chains. Don’t engage in activities that harm wildlife, such as elephant riding or tiger petting , and opt instead for a wildlife sanctuary (or better yet, attend a beach clean up or plan an hour or two of some volunteer work that interests you). Leave natural areas as you found them by taking out what you carry in, not littering, and respecting the local residents and their traditions.

Most of us travel to experience the world. New cultures, new traditions, new sights and smells and tastes are what makes traveling so rewarding. It is our responsibility as travelers to ensure that these destinations are protected not only for the sake of the communities who rely upon them, but for a future generation of travelers.

Sustainable tourism has many different layers, most of which oppose the more traditional forms of mass tourism that are more likely to lead to environmental damage, loss of culture, pollution, negative economic impacts, and overtourism.

Ecotourism highlights responsible travel to natural areas that focus on environmental conservation. A sustainable tourism body supports and contributes to biodiversity conservation by managing its own property responsibly and respecting or enhancing nearby natural protected areas (or areas of high biological value). Most of the time, this looks like a financial compensation to conservation management, but it can also include making sure that tours, attractions, and infrastructure don’t disturb natural ecosystems.

On the same page, wildlife interactions with free roaming wildlife should be non-invasive and managed responsibly to avoid negative impacts to the animals. As a traveler, prioritize visits to accredited rescue and rehabilitation centers that focus on treating, rehoming, or releasing animals back into the wild, such as the Jaguar Rescue Center in Costa Rica.

Soft Tourism

Soft tourism may highlight local experiences, local languages, or encourage longer time spent in individual areas. This is opposed to hard tourism featuring short duration of visits, travel without respecting culture, taking lots of selfies , and generally feeling a sense of superiority as a tourist.

Many World Heritage Sites, for example, pay special attention to protection, preservation, and sustainability by promoting soft tourism. Peru’s famed Machu Picchu was previously known as one of the world’s worst victims of overtourism , or a place of interest that has experienced negative effects (such as traffic or litter) from excessive numbers of tourists. The attraction has taken steps to control damages in recent years, requiring hikers to hire local guides on the Inca Trail, specifying dates and time on visitor tickets to negate overcrowding, and banning all single use plastics from the site.

Traveling during a destination’s shoulder season , the period between the peak and low seasons, typically combines good weather and low prices without the large crowds. This allows better opportunities to immerse yourself in a new place without contributing to overtourism, but also provides the local economy with income during a normally slow season.

Rural Tourism

Rural tourism applies to tourism that takes place in non-urbanized areas such as national parks, forests, nature reserves, and mountain areas. This can mean anything from camping and glamping to hiking and WOOFing. Rural tourism is a great way to practice sustainable tourism, since it usually requires less use of natural resources.

Community Tourism

Community-based tourism involves tourism where local residents invite travelers to visit their own communities. It sometimes includes overnight stays and often takes place in rural or underdeveloped countries. This type of tourism fosters connection and enables tourists to gain an in-depth knowledge of local habitats, wildlife, and traditional cultures — all while providing direct economic benefits to the host communities. Ecuador is a world leader in community tourism, offering unique accommodation options like the Sani Lodge run by the local Kichwa indigenous community, which offers responsible cultural experiences in the Ecuadorian Amazon rainforest.

" Transport-related CO 2 Emissions of the Tourism Sector – Modelling Results ." World Tourism Organization and International Transport Forum , 2019, doi:10.18111/9789284416660

" 45 Arrivals Every Second ." The World Counts.

Becken, Susanne. " Water Equity- Contrasting Tourism Water Use With That of the Local Community ." Water Resources and Industry , vol. 7-8, 2014, pp. 9-22, doi:10.1016/j.wri.2014.09.002

Kutty, Govindan M., and T.K. Raghavan Nair. " Periyar Tiger Reserve: Poachers Turned Gamekeepers ." Food and Agriculture Organization.

" GSTC Destination Criteria ." Global Sustainable Tourism Council.

Rinzin, Chhewang, et al. " Ecotourism as a Mechanism for Sustainable Development: the Case of Bhutan ." Environmental Sciences , vol. 4, no. 2, 2007, pp. 109-125, doi:10.1080/15693430701365420

" Booking.com Reveals Key Findings From Its 2019 Sustainable Travel Report ." Booking.com.

" Economic Impact Reports ." World Travel and Tourism Council .

- Costa Rica’s Keys to Success as a Sustainable Tourism Pioneer

- How to Be a Sustainable Traveler: 18 Tips

- Regenerative Travel: What It Is and How It's Outperforming Sustainable Tourism

- What Is Experiential Tourism?

- What Is Ecotourism? Definition, Examples, and Pros and Cons

- What Is Community-Based Tourism? Definition and Popular Destinations

- 3 More Rules for Sustainable Tourism

- What Is Overtourism and Why Is It Such a Big Problem?

- How to Become a Geo-Traveler

- What Is Voluntourism? Does It Help or Harm Communities?

- The World Doesn't Want Your Inukshuk

- 8 Incredible Rainforest Destinations Around the World

- 'Scattered Hotels' Are Saving Historic Villages in Italy and Beyond

- 15 Travel Destinations Being Ruined by Tourism

- How to Make Travel More Sustainable

- What's Special About the Faroe Islands

- GSTC Mission & Impacts

- GSTC History

- Market Access Program

- GSTC Board of Directors

- Assurance Panel

- Working Groups

- GSTC Sponsors

- GSTC Members

- Recruitment

- Contact GSTC

- GSTC For the Press

- Criteria Development, Feedback & Revisions

- GSTC Early Adopter Programs

- Sustainable Tourism Glossary

- SDGs and GSTC Criteria

- GSTC Industry Criteria

- GSTC Destination Criteria

- GSTC MICE Criteria

- Criteria Translations

- GSTC-Recognized Standards for Hotels

- GSTC-Recognized Standards for Tour Operators

- GSTC-Recognized Standards for Destinations

- Recognition of Standards (for Standard Owners)

- GSTC-Committed

- Certification for Hotels

- Certification for Tour Operator

- Certification for Destination

- What is Certification? Accreditation? Recognition?

- GSTC Accreditation

- Accredited Certification Bodies

- Accreditation Documents

- Public Consultations

- GSTC Auditor Training

- Sustainable Tourism Training Program (STTP)

- Upcoming Courses

- Professional Certificate in Sustainable Tourism

- Professional Certificate in Sustainable Business Travel

- GSTC Trainers and Partners

- FAQs: GSTC Training Program

- Organization Membership Application

- Destination Membership Application

- Membership Policy

- Membership Categories & Fees

- Membership Payment Options

- Webinars for GSTC Members

- Members Log In

- Upcoming Webinars

- GSTC2024 Singapore, Nov 13-16

- Upcoming Conferences

- Past Conferences

- Destination Stewardship Report

GSTC Criteria

The global sustainability standards in travel and tourism, gstc2024 singapore global conference, sentosa, singapore | 13-16 november, what is sustainable tourism.

There are many terms that float around that may sound similar but actually refer to something distinct.

Definition of Sustainable Tourism

Negative impacts to a destination include economic leakage, damage to the natural environment and overcrowding to name a few.

Positive impacts to a destination include job creation, cultural heritage preservation and interpretation, wildlife preservation landscape restoration, and more.

Sustainable tourism is defined by the UN Environment Program and UN World Tourism Organization as “tourism that takes full account of its current and future economic, social and environmental impacts, addressing the needs of visitors, the industry, the environment and host communities.”

Additionally, they say that sustainable tourism “refers to the environmental, economic, and socio-cultural aspects of tourism development, and a suitable balance must be established between these three dimensions to guarantee its long-term sustainability” ( UNEP & UNWTO , 2005: 11-12. Making Tourism More Sustainable – A Guide for Policy Makers ).

Definition of Ecotourism

Fennell described it as such: “Ecotourism is a sustainable form of natural resource-based tourism that focuses primarily on experiencing and learning about nature, and which is ethically managed to be low-impact, non-consumptive, and locally-oriented. It typically occurs in natural areas, and should contribute to the conservation or preservation of such areas” (Fennell, 1999: 43. Ecotourism: An Introduction ).

The Mohonk Agreement (2000) , a proposal for international certification of Sustainable Tourism and Ecotourism, saw ecotourism as “sustainable tourism with a natural area focus, which benefits the environment and communities visited, and fosters environmental and cultural understanding, appreciation, and awareness.”

The ecotourism definition by the Global Ecotourism Network (GEN) : “Ecotourism is responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environment, sustains the well-being of the local people, and creates knowledge and understanding through interpretation and education of all involved (visitors, staff and the visited).”

Definitions of Responsible Travel

Responsible Travel refers to the behavior of individual travelers aspiring to make choices according to sustainable tourism practices. The behaviors usually align with minimizing the negative impacts and maximizing positive ones when one visits a tourism destination.

Travelers that want to learn more about how to be a responsible traveler can visit the section on the GSTC website For Travelers .

Summary of the difference between Sustainable Tourism, Ecotourism, and Responsible Travel

Ecotourism is a niche segment of tourism in natural areas.

Sustainable Tourism does not refer to a specific type of tourism, rather it is an aspiration for the impacts of all forms of tourism to be sustainable for generations to come.

Responsible Travel is a term referring to the behavior and style of individual travelers. The behaviors align with making a positive impact to the destination rather than negative ones.

Sustainable Tourism and the GSTC Criteria

They are the result of a worldwide effort to develop a common language about sustainability in tourism. They are categorized in four pillars: (A) Sustainable management; (B) Socioeconomic impacts; (C) Cultural impacts; (D) Environmental impacts.

These standards were built on decades of prior work from industry experts around the globe. During the process of development, they were widely consulted in both developed and developing countries. They reflect our goal in attaining a global consensus on sustainable tourism.

The process of developing the Criteria was designed to adhere to the standards-setting code of the ISEAL Alliance. The ISEAL Alliance is the international body providing guidance for the management of sustainability standards in all sectors. That code is informed by relevant ISO standards .

Finally, the GSTC Criteria are the starting goals that businesses, governments, and destinations should achieve. Tourism destinations each have their own culture, environment, customs, and laws. Therefore, the Criteria are designed to be adapted to local conditions and supplemented by additional criteria for the specific location and activity.

There are three sets of Criteria

- GSTC Industry Criteria = relates to the sustainable management of private sector travel industry, focusing currently on Hotels and Tour Operators.

- GSTC Destination Criteria = relates to sustainable management of Tourism Destinations.

- GSTC MICE Criteria = relates to sustainable management of Venues, Event Organizers and Events & Exhibitions.

Learn more about Sustainable Tourism

Reading one article is not enough. The GSTC website offers those interested in learning more about sustainable tourism the needed resources. Make sure you visit the relevant pages for you:

- For Hotels & Accommodations

- For Tour Operators

- For Governments & Destinations

- For Corporate and Business Travel

You can also join one of the regular GSTC courses:

- Want to gain in-depth knowledge of the GSTC Criteria and understand sustainable tourism? The GSTC Sustainable Tourism course is for you.

- Are you a hotelier or work in the hospitality sector? GSTC Sustainable Hotel course

GSTC Sustainable Tourism Training Schedule

✓ Gain in-depth knowledge of the GSTC Criteria, the global standard for sustainability in travel and tourism. ✓ Make informed decisions on how to implement sustainability practices for your company or destination. ✓ Get ready for developing viable and actionable sustainable tourism policies and practices for your organization

I’ve participated in the course to get a comprehensive overview of destination sustainability criteria. Much more than this, the course gave me the up-to-date analysis of current trends, and a huge number of relevant cases from the destinations, the industry networks and the service providers. I strongly recommend to attend the course.

My course facilitator and teacher (Ayako and Antje) went above and beyond to answer our questions and provide us with additional resources. The course content (the GSTC Criteria) was delivered in an understandable and organized way. Learning the GSTC Criteria and how it applies to our own projects, businesses, and destinations is integral to anyone wanting to do any kind of work in the future centered around travel. I appreciated that the course was delivered in an interactive way over Zoom, and not just something we watched on YouTube. For me, being able to interact with fellow students from around the world, was a big plus. Was well worth it, and I highly recommend the course!

This course has been very relevant and provides in-depth knowledge of GSTC criteria for sustainable practices for destinations as well as the travel industry [with] plenty of real life examples and share links to plenty of reading material throughout the course. … As we move forward during these difficult COVID times, learning our lessons on the damage to nature, it becomes all the more important for industry professionals to get trained and step up efforts to embrace sustainability in all aspects of tourism. Hence, I recommend this course to all industry professionals.

This course enables participants to connect with the GSTC team directly, over an easy to use platform and network around the world. Using real life examples and detail in each of the 4 sections of the GSTC.

The GSTC training was a great way to connect, network, and engage in mind-broadening and eye-opening discussions with others in the diverse field of sustainable tourism. I would highly recommend this as a starting point for anyone interested in the journey of regenerative and sustainable tourism.

The course was great and the on- the-go discussions added great value to keep abreast of trends from across the globe. Participants from various parts of the world brought in their experiences and made the course very interesting.

Hearing about actual destinations applying Sustainable Tourism initiatives and learning from real situations practicing Sustainable Tourism, as well as the related successes and challenges, was very informative and valuable. My favorite part was the unexpected camaraderie from and connections with the other participants. I genuinely enjoyed the online discussion, sharing of ideas, and breakout groups and, overall, meeting so many others who she a passion for Sustainable Tourism. Thank you, GSTC, for a great course!

A complete holistic approach to sustainable tourism. The comprehensive lessons given each week break down the GSTC Criteria and are paired with practical examples, international experts and ‘hands on’ online workshops. The opportunity to discuss and share insights from all the participants around the world not only contributes to my own knowledge but to also my professional network. I highly recommend this course for anyone discovering sustainable tourism.

The course is quick and handy way to immerse in the issues of Sustainability in Tourism and a great kick start in starting your own business or destination program. I could have had the course even longer and especially the live sessions were great to get to know some of the other participants and share their knowledge and experiences – best practices are the best way to get started and to get valuable information. Highly recommended!

The course was so informative and presented in an engaging & interesting way. The examples & speakers gave us a lot to think about and many tangible ways that we can make a difference in our travel business. Thank you!

This course has given me an approach to the GSTC Criteria, where the basic and complete structure to move forward on sustainable paths is visualized. The reflections generated through real examples, discussions and available material are key to better internalize what sustainability means. Ideas applicable to our business and our work area appear during the course that contribute positively to one’s reality. I will recommend this course, for its contribution to the objective, honest and constructive understanding of what sustainability is.

I can only highly recommend the course for every travel and tourism professional- it is a great motivational boost to get into action and helps me support destinations in bringing the idea of destination stewardship – an inclusive and holistic approach – alive. We do not need more and more tourists, we need sustainable tourism.

Taking the GSTC training at this point in time was extremely valuable. It gave me a sustainable tourism framework to help assess what I’ve been able to accomplish and also consider the role that sustainable experiential travel may mean as we begin to inch our way out of the world of zero tourism towards something likely new and different. One other great benefit of the training was starting to get acquainted and sharing with other participants and instructors from around the globe. These connections will be valuable for a very long time to come.

I found this online course well structured and enjoyable. The trainers are really inspiring, extremely knowledgeable about the field and very supportive. The live online sessions give a great introduction to key topics, and there are online lessons, discussion forums and reference material to deepen knowledge. I feel like I have access to so much wisdom, and it is great to be part of a global community of sustainable tourism practitioners.

Thank you GSTC for such a great course. The content was relevant, the case studies were inspiring and the course structure was spot on! I can’t wait to take my learnings and inspiration and activate it across regional destinations in Australia. Keep up the great work.

What I liked the most about this course is the well-defined structure, the opinion sharing with online classmates, and the up-to-date topics. It makes the experience much more effective and enjoyable.

Excellent course that sets the foundations for sustainable tourism practice.I was very new with sustainable tourism and now after the course I have very solid understanding and skills to apply to my job. In addition, the amazing network of professionals sharing ideas is another great tool!

This course provided me with a thorough understanding of how to implement sustainable travel practices. I will definitely integrate information from this training into my work with travel organizations and destinations to help them achieve short-term progress through a long-term strategy.

The GSTC training provides a comprehensive overview of key indicators for a holistic view of sustainable tourism. The training provided an excellent opportunity to network with other tourism professionals, and to share ideas, develop plans, and comment on sustainable tourism initiatives that are being implemented in a diverse array of locations globally. I’m grateful for the connections that I made and for the helpful feedback on ideas for improving sustainability in several operations.

Useful and inspiring! The way the course is organised with lots of practical experience from colleagues in the tourism sector is indeed the most useful and interesting part of the course, [making it easier] to approach the GSTC criteria.

The GSTC course was really great to me because it gave me an in-depth knowledge about sustainable tourism. The combination of the criteria explanation and the presentation from other experts was really great, as it gave us the know-how, lots of samples and case studies. Before joining this course, I had heard about the term sustainable tourism many times, but [was not sure] what it is all about and how we can achieve it. I am glad to have gained the bigger picture of sustainable tourism. I’m developing my village to be a community based tourism destination, and now I can adopt and apply the standard locally.

A great training program that gives the participants a thorough understanding on the sustainable management of both destinations and individual businesses. Anyone from the industry – from the business or the government side – should understand the bigger picture of the destination level management as well as the industrial level so that both public and private sectors can work together for a more sustainable tourism industry.

The GSTC Sustainable Tourism Training Program provided an up-to-date perspective and holistic approach on the topic. I really enjoyed taking part in the group discussions and hearing about the realities of other destinations and their challenges.

I think the training was very useful and gave me many insights that I will use in my daily work to develop more sustainable tourism. The training class was also a good group for networking.

The Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) is the most widely recognized institution for offering sustainability courses for tourism professionals.

This is a one-of-a-kind course that provides the tools in getting you started. Not to mention, you’re also collaborating with people and organizations across the globe facing similar challenges. The feedback from fellow students was invaluable and honestly, what better way to tackle some big challenges related to the environment than with people from different countries and backgrounds. I’d take this course again just for those connections!

The [GSTC course] has been a remarkable learning experience and a great introduction to sustainable tourism. The combination of online resources, discussion forums, weekly live events with guest presenters provides a deeper understanding and useful tools in sustainable tourism. The trainers have incredible expertise in both tourism and sustainability and share their knowledge and passion about current sustainability practices. I would highly recommend this course to everyone involved in the tourism industry or have a interest in sustainable tourism.

An excellent programme run by well qualified professional staff and trainers. The guest speakers were world class and materials industry leading. A definite must for any tourism professional who is serious about making sustainable impacts for the betterment of our industry.

Amazing learning experience. Exceeded my expectations by far. Excellently organized and facilitated. Great dynamics in discussions with course participants – so much to learn from. Highly valuable best practices and interactive modules really made the best learning experience I had until now! It really motivated and inspired me to continue on the road of global sustainable tourism.

The GSTC Sustainable Tourism Training gave me the tools and network to be able to work for a more sustainable tourism sector in the area where I’m based (South Sweden). The structure with the four principles makes it easy to follow and to discuss also outside the GSTC world. The examples from the other participants were great, and we will continue sharing good and bad examples from destinations all over the world.

To work on sustainability is a never-ending story and can be overwhelming at times. The GSTC training supports a structured approach toward continuous improvement. It provides applicable tools to evaluate our sustainability performance and guidance for setting long-term strategies. It allows you to break down this massive task into achievable working packages.

The GSTC training was a great first touch point for me into the world of sustainable tourism and destination management. I loved hearing case studies from around the world and real life examples on how the GSTC criteria can make a difference. The course has enabled me to start building on these criteria within my job.

The training has enable me to go through all the GSTC Criteria thoroughly with better knowledge of sustainable tourism standard and practices. It will be useful as basic guidelines for the Foundation to use these Criteria, as the destination wants to embark in becoming a sustainable tourism destination, aiming to become GSTC-Certified.

I would definitely recommend GSTC training to absolutely everyone in the tourism industry. The entire [GSTC] framework is extremely useful and important – a framework of values and ideas that is evolving, and that is meant for us a roadmap to make things better for people and companies that may be starting from different points in the journey towards sustainability.

The quality of this training was really first class; materials, presentations, trainer support, resources and discussions. The forum helped keep everything relevant and up to date, and I also liked the format of the live events. All guest presenters were excellent; I liked that they were sharing real life experiences and not just theoretical examples. From each and every live presentation I gained ideas, reinforcements to my own experiences and enthusiasm for what I and my colleagues are doing in our own part of the world.

The STTP programme has been a good introduction to the principles of sustainable tourism. It was a good mix of presentations and cases of sustainable tourism in real-life, insights from experts from various countries and across tourism sectors and explanation of key GSTC criteria. Participants were encouraged to share their experiences and observations through discussion forums and presentations, which made the sessions more lively. The final exam is recommended for those who wish to test their ability to put these principles to practice. I highly recommend this course to tourism industry professionals wishing to incorporate sustainable tourism management at work.

The GSTC training provided me with a deep understanding of the criteria. My fellow classmates were industry experts in various sectors from around the world, bringing the criteria to life with valuable examples/discussions of how they have implemented the very practices we were learning.

My first impression was the organization, it was perfect regarding the admin efforts and the learning tools. The course materials were really useful, as well as the live sessions from which I gained a deep understanding and experience from the other participants. I really want to have the chance to thank all the team who was involved, and of course I would recommend people working in the tourism industry to join this course

The training gave me a clear understanding of the challenges we face and the actions to take to make sustainability effective, [covering] each of the main areas in a systematic way with enough technical detail for those who needed it, without losing the less technical trainees (like myself) who needed to understand the broad overview of sustainable tourism practices

The overview of standards, coupled with best practice and real world examples has been very beneficial for my work in destination management and responsible tourism development. The ability to meet likeminded industry colleagues, who are working in this arena was also highly valuable.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Related posts.

Petra joins GSTC

Tobu Top Tours joins GSTC

Travel Nevada joins Global Sustainable Tourism Council

National Geographic content straight to your inbox—sign up for our popular newsletters here

Coral reforestation helps restore desolated reefs around Landaa Giraavaru Island on Baa Atoll in the Republic of Maldives.

For travelers, sustainability is the word—but there are many definitions of it

Most people want to support sustainable tourism, even though the concept remains fuzzy.

The word “overtourism” is a relatively new term—but its novelty has not diminished the portent of its meaning: “An excessive number of tourist visits to a popular destination or attraction, resulting in damage to the local environment and historical sites and in poorer quality of life for residents,” according to the Oxford Dictionary .

As travel recovers from pandemic lows, travelers are once again experiencing the consequences of overtourism at enticing, but crowded, destinations. The UN World Tourism Organization, along with public and private sector partners, marks September 27 as World Tourism Day and uses this platform to discuss tourism’s social, political, economic, and environmental impacts.

This day highlights the importance of sustainable tourism —a framework for engaging travelers and the travel industry at large in supporting goals that include protecting the environment, addressing climate change, minimizing plastic consumption , and expanding economic development in communities affected by tourism.

Getting the facts

A National Geographic survey of 3,500 adults in the U.S. reveals strong support for sustainability. That’s the good news—but the challenge will be helping travelers take meaningful actions. According to the survey—which was conducted in 2019—while 42 percent of U.S. travelers would be willing to prioritize sustainable travel in the future, only 15 percent of these travelers are sufficiently familiar with what sustainable travel actually means.

( Learn about how to turn overtourism into sustainable global tourism .)

In the National Geographic survey, consumers most familiar with sustainable travel are young: 50 percent are 18 to 34 years old. Among travelers who understand the sustainable travel concept, 56 percent acknowledge travel has an impact on local communities and that it’s important to protect natural sites and cultural places.

The survey has informed National Geographic’s experiential travel and media businesses and sparked conversations for creating solutions around sustainability. Our travel content focuses on environmentally friendly practices, protecting cultural and natural heritage, providing social and economic benefits for local communities, and inspiring travelers to become conservation ambassadors. In short, we see every National Geographic traveler as a curious explorer who seeks to build an ethic of conserving all that makes a destination unique.

Building better practices

National Geographic Expeditions operates hundreds of trips each year, spanning all seven continents and more than 80 destinations. Rooted in the National Geographic Society ’s legacy of exploration, the company supports the Society's mission to inspire people to care about the planet by providing meaningful opportunities to explore it. Proceeds from all travel programs support the Society’s efforts to increase global understanding through exploration, education and scientific research.

National Geographic Expeditions offers a range of group travel experiences, including land expeditions, cruises, and active adventures, many of which take place around eco-lodges that are rigorously vetted for their sustainability practices.

These independent lodges incorporate innovative sustainability practices into their everyday operations, including supporting natural and cultural heritage, sourcing products regionally, and giving back to the local community.

For example, South Africa’s Grootbos Lodge launched a foundation to support the Masakhane Community Farm and Training Centre. Through this program, the lodge has given plots of land to local people who have completed the training, increasing their income and access to local, healthy foods; so far the program has benefitted more than 138 community members.

As a media brand, National Geographic encourages travelers to seek out and support properties that embrace a mission to help protect people and the environment. Not only do these accommodations make direct and meaningful impacts in their own communities, but staying at one helps educate travelers in effective ways to preserve and protect the places they visit.

Supporting sustainability

The travel industry is crucially dependent on the health of local communities, environments, and cultures. As many experts note, we need to invest in the resiliency of places affected by overtourism and climate change to achieve sustainable tourism.

( Should some of the world’s endangered places be off-limits to tourists ?)

National Geographic’s coverage stresses the importance of reducing our carbon footprint and encourages travelers to step off the beaten path and linger longer, respect cultural differences and invest in communities, reconnect with nature and support organizations that are protecting the planet. Here are 12 ways to travel sustainably , reported by our staff editors.

Storytelling can help by highlighting problems brought on by tourism and surfacing practices and technologies to mitigate negative impacts. A key goal of our storytelling mission at National Geographic Travel is to dig deeper into the topic of sustainable tourism and provide resources, practical tips, and destination advice for travelers who seek to explore the world in all its beauty—while leaving behind a lighter footprint.

Become a subscriber and support our award-winning editorial features, videos, photography, and much more.

For as little as $2/mo.

Related Topics

- SUSTAINABILITY

- SUSTAINABLE TOURISM

- ENVIRONMENT AND CONSERVATION

- PEOPLE AND CULTURE

- CLIMATE CHANGE

You May Also Like

6 tips to make your next beach trip more sustainable

Can tourism positively impact climate change in the Indian Ocean?

B Corps can help us travel more responsibly—but what are they?

6 eco-conscious alpine resorts around the world

Welcome to Hydra, the Greek island that said no thanks to cars

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Hand-Picked Top-Read Stories

Vision Zero: A Comprehensive Guide

- Environment

- Transportation

Advantages of Public Transport: 20 Reasons to Make the Shift Today

- Planet earth

CNG Fuel: A Comprehensive Guide

Trending tags.

- Zoning Laws

- Zero-waste living

- zero-waste kitchen

- workplace safety

- workplace charging

- WineTasting

- Sustainable Tourism

Sustainable Tourism Practices and Destinations: Examples from Around the World

Sustainable Tourism Practices: Sustainable tourism is a growing trend in the travel industry that focuses on minimizing the environmental and social impact of tourism while providing economic benefits to local communities. From eco-friendly accommodations to responsible travel practices, there are many ways that tourism can be made more sustainable. Around the world, destinations and businesses are implementing sustainable tourismthat support conservation, reduce carbon emissions, and promote local cultural heritage. These efforts not only benefit the planet, but also provide a unique and authentic travel experience for visitors. In this context, we will explore some of the sustainable tourism and destinations from around the world that are leading the way in promoting responsible and ethical tourism.

Here are 40 examples of sustainable tourism and destinations from around the world:

- The Galapagos Islands, Ecuador – A protected wildlife sanctuary that limits visitor numbers to prevent environmental damage and promote sustainable tourism.

- Costa Rica – A country that has made a strong commitment to sustainable tourism, with a focus on eco-tourism, community-based tourism, and conservation efforts.

- Bhutan – A country that measures its economic success through a Gross National Happiness index, which includes the protection of the environment and cultural heritage.

- Norway – A country that is known for its sustainable tourism, including eco-friendly transportation, green energy, and sustainable tourism certification programs.

- The Netherlands – A country that is promoting sustainable tourism through initiatives such as green hotels, bike-friendly cities, and nature conservation programs.

- New Zealand – A country that has a strong focus on sustainable tourism, including eco-tourism, conservation efforts, and responsible travel practices.

- The Amazon Rainforest, Brazil – A region that has adopted sustainable tourism to promote conservation and support local communities.

- The Great Barrier Reef, Australia – A protected marine park that promotes sustainable tourism, such as reducing carbon emissions and protecting the natural environment.

- Kenya – A country that has implemented sustainable tourism, including wildlife conservation, community-based tourism, and eco-friendly lodges.

- Iceland – A country that is promoting sustainable tourism through eco-friendly transportation, renewable energy, and eco-certification programs.

- South Africa – A country that is known for its conservation efforts, including wildlife protection and community-based tourism.

- The Azores, Portugal – A group of islands that is promoting sustainable tourism through eco-tourism, whale watching, and nature conservation programs.

- The Serengeti, Tanzania – A protected wildlife sanctuary that promotes responsible tourism practices, such as reducing carbon emissions and supporting local communities.

- The Cook Islands, Pacific Ocean – A group of islands that is committed to sustainable tourism, including protecting the environment and supporting local communities.

- Thailand – A country that has implemented sustainable practices, including community-based tourism, wildlife conservation, and responsible travel.

- The Faroe Islands, Denmark – A group of islands that is promoting sustainable tourism through eco-friendly transportation, sustainable seafood, and nature conservation programs.

- The Lake District, England – A protected national park that promotes sustainable tourism, such as reducing carbon emissions and supporting local communities.

- The Annapurna Region, Nepal – A region that is promoting sustainable tourism through community-based tourism, conservation efforts, and responsible trekking practices.

- The Maasai Mara, Kenya – A protected wildlife reserve that promotes sustainable practices, such as reducing carbon emissions and supporting local communities.

- The Blue Mountains, Australia – A protected national park that promotes sustainable tourism practices, such as reducing carbon emissions and supporting local communities.

- Guna Yala, Panama – A protected indigenous territory that promotes sustainable tourism, such as supporting traditional livelihoods and preserving cultural heritage.

- The Isle of Eigg, Scotland – An island that is promoting sustainable tourism through renewable energy, eco-friendly accommodations, and community-based tourism initiatives.

- The San Blas Islands, Panama – A group of islands that is promoting sustainable tourism through eco-tourism, community-based tourism, and responsible travel practices.

- The Burren, Ireland – A protected national park that promotes sustainable practices, such as reducing carbon emissions and supporting local communities.

- The Bay of Fundy, Canada – A protected marine park that promotes sustainable tourism practices, such as reducing carbon emissions and supporting local communities.

- The Lofoten Islands, Norway – An archipelago that is promoting sustainable tourism through eco-friendly transportation, responsible fishing, and community-based tourism initiatives.

- The Tongariro National Park, New Zealand – A protected national park that promotes sustainable tourism, such as reducing carbon emissions and supporting local communities.

- The Danube Delta, Romania – A protected wetland that promotes sustainable tourism practices, such as eco-tourism and responsible travel practices.

- The Douro Valley, Portugal – A region that is promoting sustainable tourism through eco-tourism, responsible wine tourism, and community-based tourism initiatives.

- The Lake Titicaca, Peru/Bolivia – A protected lake that promotes sustainable tourism, such as preserving cultural heritage and supporting traditional livelihoods.

- The Everglades, United States – A protected wetland that promotes sustainable tourism, such as reducing carbon emissions and supporting local communities.

- The Cinque Terre, Italy – A protected coastal area that promotes sustainable tourism practices, such as reducing carbon emissions and supporting local communities.

- The Mekong Delta, Vietnam – A region that is promoting sustainable tourism through eco-tourism, responsible travel practices, and community-based tourism initiatives.

- The Lake District, Chile – A protected national park that promotes sustainable tourism practices, such as reducing carbon emissions and supporting local communities.

- The Sinharaja Forest Reserve , Sri Lanka – A protected rainforest that promotes sustainable tourism, such as eco-tourism and responsible travel practices.

- The Jasper National Park, Canada – A protected national park that promotes sustainable tourism practices, such as reducing carbon emissions and supporting local communities.

- The Arctic, various countries – A region that is promoting sustainable tourism through eco-tourism, responsible travel practices, and nature conservation programs.

- The Torres del Paine National Park, Chile – A protected national park that promotes sustainable tourism, such as reducing carbon emissions and supporting local communities.

- The Sagarmatha National Park, Nepal – A protected national park that promotes sustainable tourism practices, such as eco-tourism and responsible trekking practices.

- The Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve, Costa Rica – A protected cloud forest that promotes sustainable tourism practices, such as eco-tourism and nature conservation programs.

These are just a few more examples of the many destinations and businesses around the world that are adopting sustainable tourism. With a growing focus on responsible and ethical tourism, sustainable tourism is becoming an increasingly important industry worldwide.

Similar Articles

- Green Hiking

- How To Save Water

- What is an Eco Lodge?

Frequently Asked Questions About Sustainable Tourism Practices

What is sustainable tourism?

Sustainable tourism is a form of tourism that focuses on minimizing the environmental and social impact of travel while providing economic benefits to local communities.

What are some sustainable tourism practices?

Some sustainable tourism practices include supporting conservation efforts, reducing carbon emissions, promoting local cultural heritage, and supporting local communities through community-based tourism initiatives.

Why is sustainable tourism important?

Sustainable tourism is important because it helps to preserve natural and cultural resources, provides economic benefits to local communities, and promotes responsible and ethical travel practices.

How can travelers practice sustainable tourism?

Travelers can practice sustainable tourism by supporting eco-friendly accommodations, engaging in responsible travel practices, supporting local communities, and minimizing their carbon footprint.

What are some examples of sustainable tourism destinations?

Some examples of sustainable tourism destinations include national parks, protected areas, eco-tourism lodges, and community-based tourism initiatives.

How can tourism businesses implement sustainable tourism practices?

Tourism businesses can implement sustainable practices by reducing their carbon emissions, supporting local communities, promoting conservation efforts, and adopting eco-friendly practices.

What is community-based tourism?

Community-based tourism is a form of tourism that involves local communities in the tourism industry, providing economic benefits while preserving local culture and traditions.

What is responsible tourism?

Responsible tourism is a form of tourism that focuses on minimizing the environmental and social impact of travel while providing economic benefits to local communities and promoting cultural awareness.

What is the difference between sustainable tourism and ecotourism?

Sustainable tourism is a broader concept that encompasses all forms of tourism that are socially, economically, and environmentally responsible, while ecotourism is a specific form of tourism that focuses on nature-based experiences that support conservation efforts.

How does sustainable tourism benefit local communities?

Sustainable tourism benefits local communities by providing economic benefits through job creation and supporting local businesses, while also preserving cultural heritage and traditions.

How can tourists ensure they are practicing sustainable tourism?

Tourists can ensure they are practicing sustainable tourism by choosing eco-friendly accommodations, engaging in responsible travel practices, supporting local communities, and minimizing their carbon footprint.

What role do governments play in promoting sustainable tourism?

Governments play an important role in promoting sustainable tourism by establishing policies and regulations that support conservation efforts, promoting sustainable practices, and providing funding for sustainable tourism initiatives.

What are some challenges to implementing sustainable tourism practices?

Some challenges to implementing sustainable tourism practices include the high cost of implementing eco-friendly practices, lack of awareness among tourists, and limited resources in developing countries.

What is the role of tourism businesses in promoting sustainable tourism?

Tourism businesses play a critical role in promoting sustainable tourism by adopting eco-friendly practices, supporting conservation efforts, and engaging with local communities to ensure their economic benefits are sustainable.

What is the impact of sustainable tourism on the environment?

Sustainable tourism aims to minimize the impact of tourism on the environment by reducing carbon emissions, supporting conservation efforts, and promoting eco-friendly practices. This can have a positive impact on the environment by preserving natural resources and reducing pollution.

What is the role of tourists in promoting sustainable tourism?

Tourists have a crucial role to play in promoting sustainable tourism by supporting eco-friendly accommodations, engaging in responsible travel practices, supporting local communities, and minimizing their carbon footprint.

What is the role of local communities in sustainable tourism?

Local communities play a vital role in sustainable tourism by providing unique cultural experiences, supporting conservation efforts, and benefitting from the economic opportunities that tourism can bring. Sustainable tourism initiatives often involve working with local communities to ensure their voices are heard and their needs are met.

How can sustainable tourism help preserve cultural heritage?

Sustainable tourism can help preserve cultural heritage by supporting local cultural practices and traditions, promoting cultural awareness, and providing economic benefits to local communities. In doing so, it helps to maintain and celebrate cultural diversity and promote the value of cultural heritage.

What is the impact of sustainable tourism on the economy?

Sustainable tourism can have a positive impact on the economy by providing job opportunities, supporting local businesses, and promoting economic growth in tourism-dependent communities. It can also encourage investment in infrastructure and services, leading to long-term economic benefits.

What is the role of education in promoting sustainable tourism?

Education plays a critical role in promoting sustainable tourism by raising awareness among tourists, tourism businesses, and local communities. It can help to promote best practices, encourage responsible travel behavior, and foster a culture of sustainability.

How can technology be used to promote sustainable tourism?